Of transition and trade deals

The UK will not be able to replicate the EU’s free trade agreements ready for March 30th 2019. The only solution is to ask the EU for help.

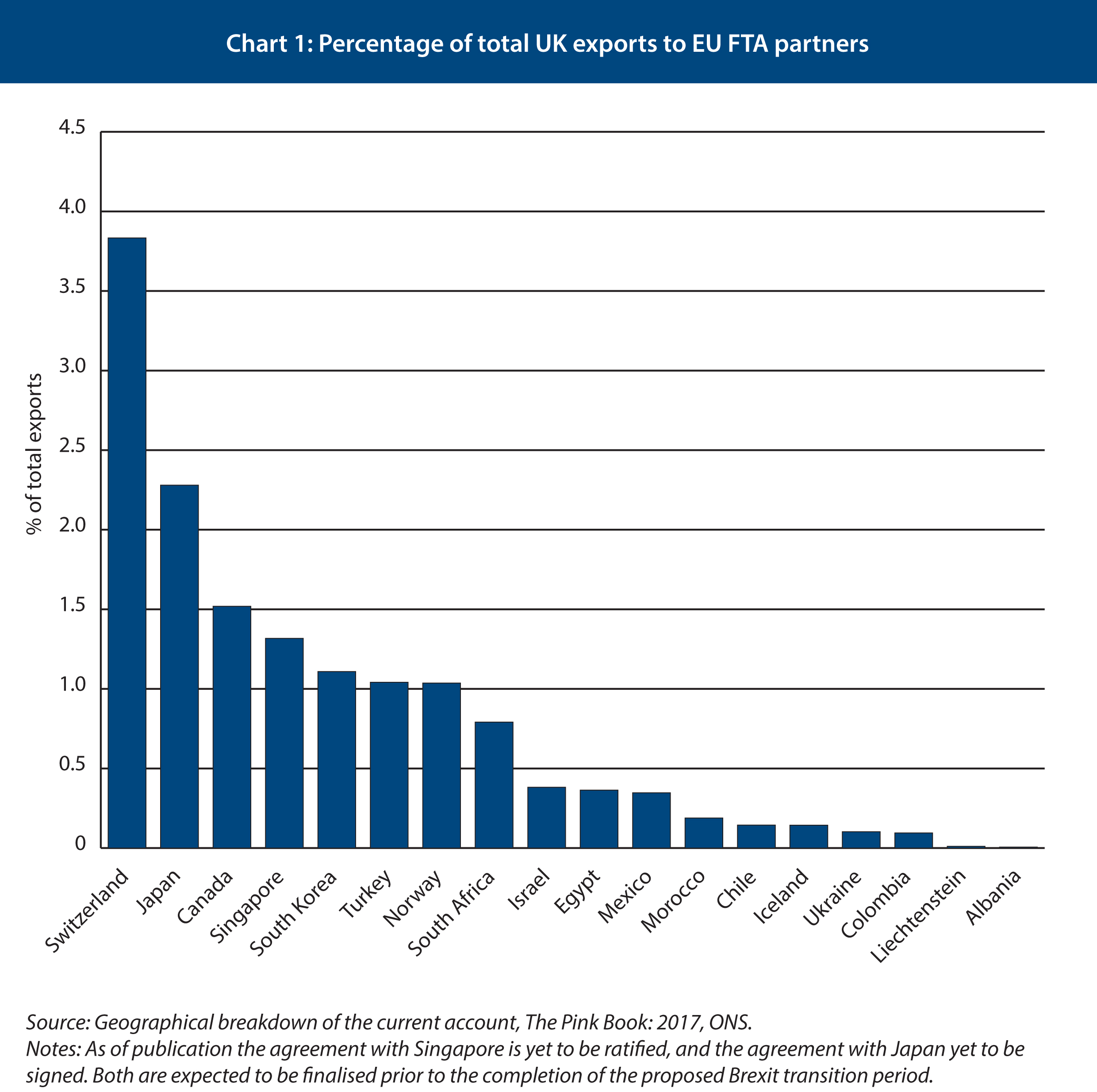

Because of Brexit, the UK will no longer benefit from over 40 EU free trade agreements (FTAs) as of March 30th 2019. This is set to be the case whether the UK enters an interim ‘status quo’ transition agreement or not. These FTAs are with countries receiving 11 to 15 per cent of UK total exports, including Switzerland, Turkey and Canada (see Chart 1). While this does not sound like much, it should be understood in the context of the EU (43 per cent) and US (18 per cent) eating up the majority of UK exports, leaving little left for the rest.

Avoiding the cliff edge is not something the UK can do by itself. Ministerial proclamations that the UK will have these agreements replicated ready for exit day should not be taken seriously. With every best intention there is simply too much to do, and the urgency is solely the UK’s. Expediting the process will not be a priority for the EU’s FTA partners, whose exporters will still be able to sell into the UK under the same conditions as now throughout the transition period. While the UK faces an imminent cliff edge, countries with a trade agreement with the EU do not. And it requires two to tango.

The best option is for the UK to convince the EU to assist it in fudging an interim solution – an example of which is given below. This will not be easy. The short-term cost to the EU of not helping is relatively small. This should not stop the UK from formally asking.

The trouble with transition

While the transition agreement is still subject to negotiation, the Commission’s draft proposal states that once the UK has withdrawn from the EU it will “no longer benefit from the agreements concluded by the Union”. This is not pernicious, simply a statement of fact: the UK will no longer be an EU member, therefore the EU’s international treaties will no longer apply to it. The proposal further specifies that the 27 will only assist the UK in finding a way to extend the agreements during the transition period if it is deemed to be in the interest of the EU.

As well as binding the UK to the EU’s single market and customs union, the draft proposal seeks to ensure that the UK continues to apply the bloc’s external tariff rates and performs the same border checks with non-EU countries.

This could easily result in a scenario in which UK exporters are no longer able to take advantage of the EU’s existing free trade agreements, but exporters located in countries with EU FTAs would continue to benefit from preferential access to the UK market on the same terms as now. To give a practical example: during the proposed transition, Korean car exporters would still be able to sell cars into the UK without being subject to border tariffs under the provisions of the EU-South Korea free trade agreement. UK car exporters selling into Korea, on the other hand, would no longer be covered by the agreement and would face Korea’s tariffs of 8 per cent.

Leaked member-state amendments to the Commission’s transition text leave open the possibility of the UK being able to sign new trade agreements during the transition. This may appeal to a UK government which has held up the ability to sign new trade agreements as a barometer of Brexit’s success. However, it clarifies that the UK would be unable to implement anything agreed until the transition is over unless permission is granted by the EU. Additionally, many countries will be unwilling to commit to substantive negotiations prior to the conclusion of a future EU-UK agreement.

For many, the UK foregoing its membership of EU FTAs is viewed as an inevitable consequence of Brexit.

Why can’t the UK just copy & paste?

The UK’s existing solution is to replicate all of the EU's FTAs and relevant treaties ready for exit day. Liam Fox, the Secretary of State for International Trade, is confident this is possible, saying in October: "I hear people saying 'oh, we won't have any [free trade agreements] before we leave'. Well believe me we'll have up to 40 ready for one second after midnight in March 2019." Despite his optimism, the clock is ticking and there is little reason to think he will achieve his objective.

The UK’s primary issue is that this is not simply a cut and paste job. The partner countries have their own desires, domestic processes and politics to deal with too. While many have signaled that they are happy to use the existing EU agreement as a template, Brexit is also an opportunity to push for upgrades. South Africa, for example, has indicated that it will seek to renegotiate provisions on market access for agriculture and food hygiene standards. This takes time and institutional capacity. When you factor in a lack of urgency on the part of the partner countries – as stated above, their exporters will continue to receive preferential access throughout the transition period regardless – the notion that all of these agreements will be ready to go on 30th March 2019 seems little more than a pipe dream.

The UK should instead ask the EU for help.

The ‘Guernsey option’

If, rather than a transition, the UK and EU were to agree to extend the Article 50 timeframe all of the issues in regards to third country trade agreements and treaties would cease to be a problem. Economically and legally this is far and away the most sensible option. But this would see the UK remain an EU member for the foreseeable future and politically, on both sides, it appears to be unthinkable.

So what’s left on the table is a fudge. This could take many forms, but in practice it boils down to the EU and UK staring down the EU’s FTA partners and daring them to blink.

One option would be to source the fudge from the Channel Islands. First proposed by George Peretz QC of the UK Trade Forum, the so-called ‘Guernsey option’ finds a ready-made solution in the Crown Dependencies’ unusual international status.

Guernsey is not part of the EU nor the UK, but its complicated relationship with the UK means that, under international law, it is considered as part of the UK territory. And in areas where the UK has ceded competence to the EU vis-à-vis international treaties with third countries, part of the EU. This is a precedent for a non-EU member being covered by the EU’s external trade policy. In theory, such a status could be made available to the UK throughout the transition.

Guernsey is also able to, so long as it receives the UK’s permission, negotiate its own international agreements. If applied to the UK, this would allow it to finalise the replication of the existing EU FTAs, ready for the end of the transition, and perhaps even negotiate, if not implement, new agreements.

The Guernsey option would however require bags of goodwill and considerable EU assistance. Theoretically, third countries may still object to such an approach. But any country objecting would struggle to prove any harm to its exporters, as for its purposes nothing would have changed, and it is probably unlikely that they would want to remove preferential market access for UK companies, if both the EU and the UK stood united.

Asking, and convincing, the EU to work with the UK to reach a mutually beneficial outcome should be an immediate priority for the UK during phase two of the Brexit negotiations.

What’s in it for me?

The above solution, or something to similar effect, requires EU-27 co-operation. Whether this will be forthcoming is another question. Assistance is far from guaranteed. For many, the UK foregoing its membership of EU FTAs is viewed as an inevitable consequence of Brexit. When asked whether EU trade agreements would apply to the UK after Brexit, Cecilia Malmström, the EU commissioner for trade, said in December: “There has been talk of a transition period - that is something that will be decided. But the other trade agreements with the third countries, with Canada, with South Korea and others they will have to leave.”

Yet the European Council guidelines for the Brexit negotiations state that where the UK is expected to “honour its share of all international commitments contracted in the context of its EU membership” the EU and UK should discuss a possible common approach. This has already led to the UK and EU tabling joint proposals at the World Trade Organisation. If the UK were to ask for assistance, the EU would be likely to oblige.

The UK no longer being party to EU FTAs during the transition would also have implications for EU exporters. In order to benefit from the advantages of a trade agreement the EU has with another country, an EU exporter must prove that the product it is selling is actually from, or has had sufficient work done on it (subject to myriad terms and conditions) in, the EU. Whereas before Brexit, EU-27 exporters could treat inputs from the UK as ‘local’ for the purpose of qualifying for an FTA, during the transition this will no longer be the case.

This is a much bigger problem for UK exporters – the total proportion of UK inputs sourced from the EU is 9.3 per cent, the reverse is only 1.4 per cent – but it could still throw up complications for some EU companies. However, helping the UK carry over its FTAs throughout the transition would grant affected EU exporters a little more time to adjust, and would likely be appreciated. It would also buy time for the UK and EU to, if deemed in the interest of both, negotiate trilaterally with the EU’s FTA partners to allow for UK and EU inputs to continue to be accounted for as local for the purpose of qualifying for the existing and replicated agreements respectively. This is known as cumulation.

Finding a solution is entirely dependent on EU goodwill. Asking, and convincing, the EU to work with the UK to reach a mutually beneficial outcome should be an immediate priority for the UK during phase two of the Brexit negotiations. The UK falling out of the EU’s trade agreements and treaties on the 30th March 2019 might be a likely consequence of Brexit, but it need not be inevitable.

Sam Lowe is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Add new comment