The EU budget in a larger Union: Key issues and open questions

- Estimates of the impact of enlargement dispel the myth that it would bust the EU’s budget: the rise in EU spending would be manageable if Ukraine, Moldova and all Western Balkan candidates joined the Union. However, some of the current member-states would receive lower transfers from the EU. Therefore the distributional effects of enlargement need to be addressed to ensure it has broad-based political support.

- EU enlargement should prompt a rethink of the largest budget lines – the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and cohesion policy. Without reforms, CAP transfers would increase by 22-25 per cent, and Ukraine would become their main beneficiary, given the scale of its agricultural sector. But the CAP needs reforming to target smaller, needier farms and to tie transfers to sustainable production practices.

- Under current rules, overall cohesion spending would increase by 7 per cent following large-scale enlargement. At the same time, cohesion policy should become more performance-based, tying disbursements to reforms and concrete investments. The experience from the EU’s post-pandemic investment programme, NextGenerationEU (NGEU), shows that both infrastructure investments and institutional reforms are needed to boost growth.

- The energy mix and economic structure of candidate countries are generally more carbon intensive than those of the EU-27. Financial support for investing in clean electrification and grid infrastructure, as well industrial and transport decarbonisation, is going to be essential for new entrants to meet EU climate goals.

In the aftermath of Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine, what had been a long-dormant EU accession process has been revived. Since 2022, the European Council has granted candidate status to Ukraine, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Georgia. Today, there are nine candidate countries to access the EU: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Türkiye and Ukraine. Kosovo has also applied to become a candidate. Negotiations have already started and accelerated with several of them, whereas Georgia has since frozen its accession application. Türkiye’s accession bid has long stalled, so it is not considered for the purpose of this analysis.

The prospect of a large wave of EU enlargement by 2030 or even 2035 might be optimistic. But the path towards enlargement is set, and today’s geopolitical context appears to be more favourable to it than five years ago. Some European leaders are advocating for a fast accession process, like French President Emmanuel Macron. But some member-states are still reticent in private, particularly because they think a larger Union would require substantial reforms of voting rules and institutions to function better and avoid political deadlock. This ambivalence is due to the need to balance two forces: the threats posed by a more aggressive Russia and America’s retrenchment make enlargement more urgent, while ensuring effective decision-making in an EU with potentially more than thirty member-states requires institutional reforms (including to avoid post-accession backsliding in the rule-of-law) – and reforms take time.

Enlargement, be it fast or slow, will affect all areas of EU policy-making. This insight focuses on the implications for the EU budget, including EU financial support to facilitate the achievement of climate targets and the decarbonisation of the EU energy system.

The EU budget today: Key elements

The EU’s seven-year budget – formally called the multiannual financial framework, or MFF – is financed through so-called own resources of the Union. Today, these mainly include:

- Direct contributions from EU countries proportional to their gross national income;

- Customs duties levied on imports from outside the EU;

- A small part of the value-added tax (VAT) collected by each EU country;

- A contribution based on the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste in each EU country.

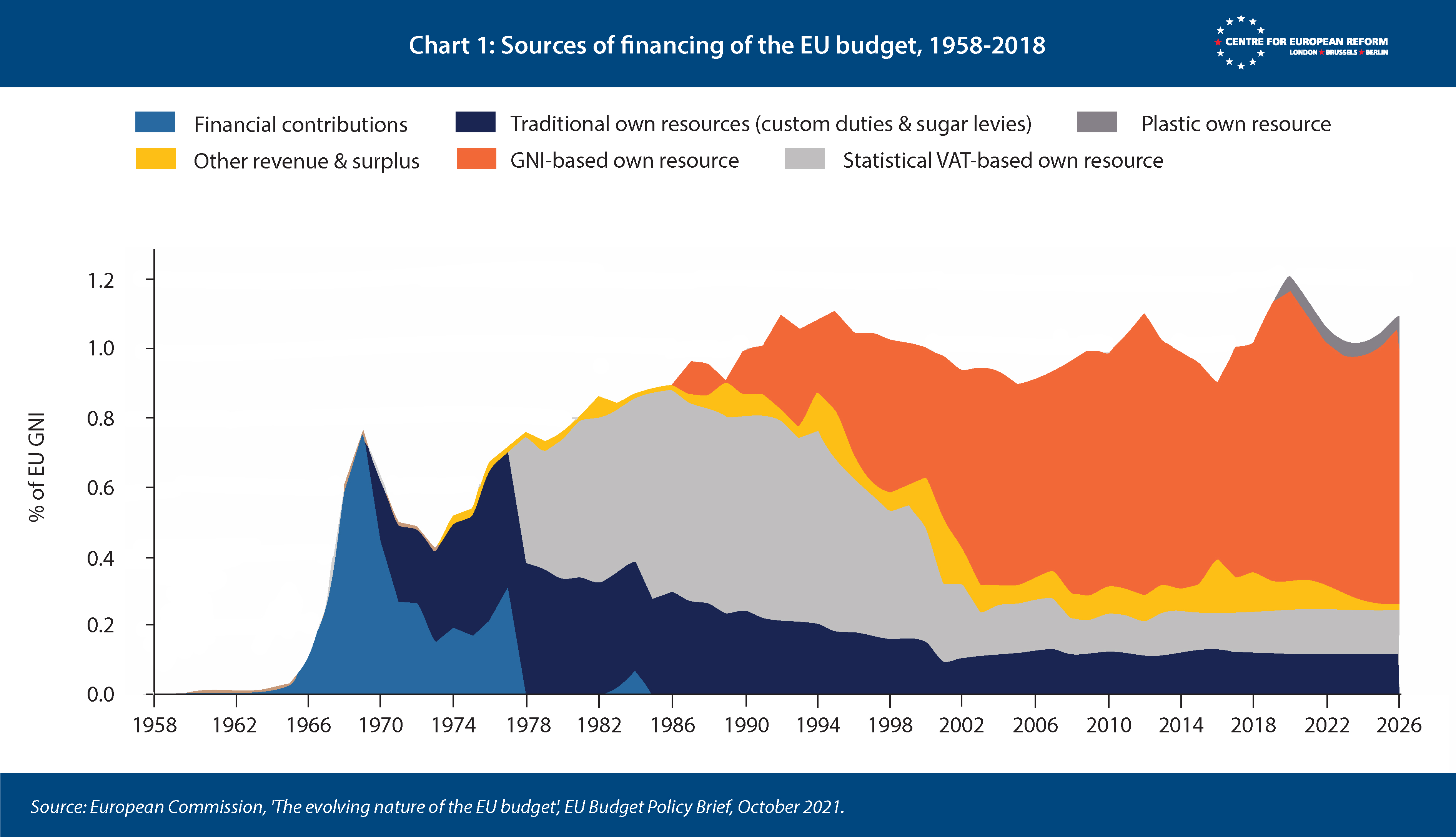

Direct contributions based on gross national income are the largest source of financing today, whereas revenues from customs duties and sugar levies have considerably shrunk over the decades (Chart 1). The Commission can also raise funds by issuing debt on capital markets, as it has done to finance the post-pandemic recovery fund NextGenerationEU (NGEU).

The discussion on new sources of funding for the EU budget has been reignited by the need to repay the bond issuance for NGEU. In 2021, the Commission proposed some new resources for the MFF, based on part of the revenues from the EU carbon pricing instruments (the Emissions Trading System and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) and on profits of multinational companies under the Global Agreement on Corporate Taxation (which affects revenues from taxes on corporate profits of large multinationals). While there has been no agreement on these additional revenue streams so far, their necessity has only increased, because the EU needs to respond to crises more quickly and to finance investments in European public goods like power grids and defence kit.

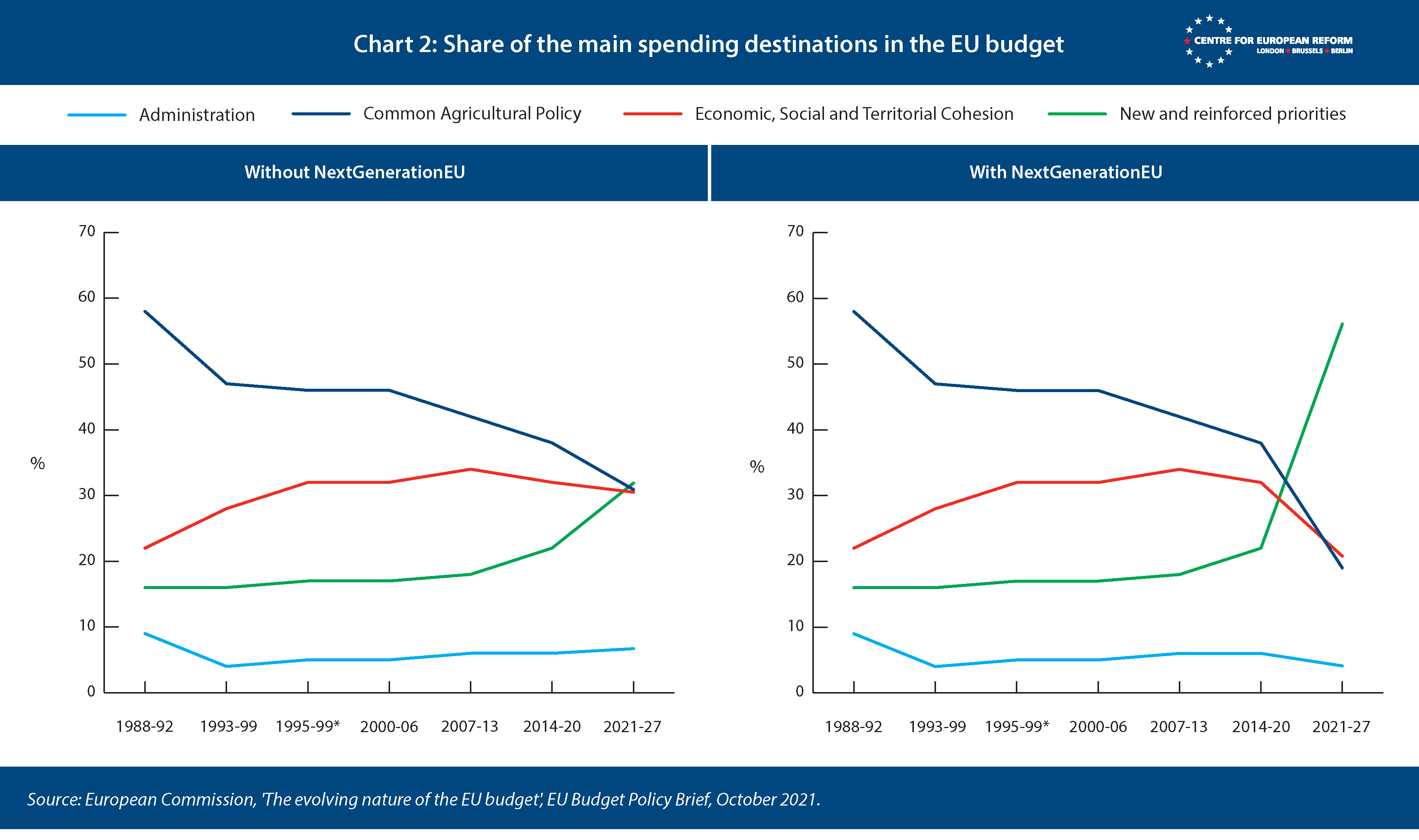

The focus of EU spending has changed in recent decades, with funds for farm support falling and support for the energy transition rising. As Chart 2 shows, while the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) represented 60 per cent – the lion’s share of the EU budget – in 1988-1992, it is now about 30 per cent. Funds dedicated to economic, social and territorial cohesion have plateaued around 30 per cent. Conversely, funds devoted to new and reinforced priorities, such as the energy transition, have surged to over 30 per cent of the EU budget – and almost 60 per cent if we consider that the MFF is complemented by the NGEU between 2021 and 2027. Notably, 30 per cent of the combined value of the MFF and NGEU is devoted to investments to fight climate change. But the NGEU fund will run out in 2026 – so there is a real risk of investments for the energy transition falling off a cliff.

The implications of enlargement for the MFF

A new wave of EU enlargement is expected to increase spending on cohesion and agriculture, but it would also increase the need for EU financial support for climate action and the energy transition. But what are the precise implications for each of these streams of funding?

Cohesion policy aims to create a level playing field within the single market by addressing imbalances in infrastructure, public services and skills between EU countries and regions. Cohesion funds (€392 billion in 2021-2027) are allocated to regions in need, defined as those with a GDP per capita lower than the EU average. For example, Ukraine’s GDP per capita is around €4,600 and Serbia’s is just above €11,300 – both considerably lower than the EU average, which stood around €38,400 in 2023. The accession of new members with lower GDP per capita would change the distribution of funds for existing ones, as some regions previously receiving net transfers would find themselves above the new EU average.

The CAP aims to support EU farmers’ incomes, increase agricultural productivity and ensure affordable food supply. It is composed of Pillar I, fully financed through EU funds and largely allocated to farmers through direct transfers (€291.1 billion in the current MFF), and Pillar II, co-financed through EU funds and member-states’ budgets to support the sustainable development of rural areas (€95.5 billion). CAP funds are not allocated based on a single formula, but direct payments to farmers depend on a country’s agricultural land surface. The agricultural sector of several candidate countries is vast, contributing to over 10 per cent of GDP in Albania, Moldova and Ukraine – compared to 1.6 per cent in the EU.

Under the current system of payments, new members would become net beneficiaries of EU CAP and cohesion funds, meaning they would obtain more funds than they would pay in contributions. At the same time, EU members that are currently net beneficiaries would not necessarily turn into net contributors. For instance, a recent simulation by Bruegel indicates that under current EU budget rules, the EU budget following large-scale enlargement (including Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Serbia and Ukraine) would increase from 1.12 per cent of GDP to 1.23 per cent of GDP. Current net beneficiaries would receive slightly less from the EU budget once these nine countries join the EU, but this drop would be minor relative to what some countries have already experienced between the 2014-2020 MFF and 2021-2023 due to catch-up growth. For example, Hungary’s net transfers from the EU shrunk from 3.93 to 2.97 per cent of its gross national income over this period. Additionally, a larger single market is expected to raise tax revenues through increased trade among EU countries and, consequently, result in higher productivity.

Enlarging the EU to nine new members would require a manageable EU budget increase from 1.12 per cent of GDP to 1.23 per cent of GDP.

A recent report by the Jacques Delors Institute and others for the European Parliament’s Committee on Budgets simulates three scenarios based on the speed of enlargement. One scenario foresees gradual integration only, with no countries joining the EU during the next MFF but continuing to receive pre-accession funding; another considers a ‘small bang’ scenario whereby all six Western Balkans candidates (Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia) join the EU by 2030; and the third assesses a ‘big bang’ scenario in which Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine also join the EU by 2030. Assuming the current rules for allocating both cohesion and CAP funds remain in place, the accession of all six Western Balkans countries would lead to a localised drop in cohesion transfers to Romania (-15 per cent) and Hungary (-21 per cent) relative to the gradual integration scenario with no immediate enlargement. The accession of nine new members by 2030 would cause a sharper drop in EU average GDP per capita, and as such it would cause a larger reshuffling in cohesion policy funds. Specifically, Spain, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Latvia would see a 15-22 per cent drop in cohesion policy funds relative to a gradual integration scenario. Keeping the CAP Pillar I budget constant in real terms would lead to cuts in CAP transfers to current member-states – on average 2.5-3.5 per cent in the ‘small bang’ scenario and 15 per cent in the ‘big bang’ scenario. Only Spain would eventually shift from net beneficiary to net contributor in the latter scenario.

Depending on the speed and breadth of enlargement, CAP transfers to existing member-states could undergo cuts between 2.5 and 15 per cent on average.

These estimates suggest that the overall budget impact of enlargement on the EU budget is manageable. However, to ensure maximum political and social acceptability of the enlargement process, it is crucial to introduce a mechanism to smooth the budgetary impact and to manage the distributional effects it would have on current member-states. This also requires rethinking large spending items of the EU budget – the CAP as well as cohesion policy – and considering how to meet pressing priorities from decarbonisation to economic competitiveness and rearmament.

Enlargement and the Common Agricultural Policy

The weight of the CAP relative to the EU budget has continuously diminished for decades (Chart 2). In a recent communication about the next MFF, the Commission states that CAP disbursements should be better targeted towards farmers who need support most. The need to reform the CAP ahead of a large wave of EU enlargement is also underscored by simple arithmetic: were the CAP to be applied to new members with its current rules, the total CAP budget would need to increase by an estimated 22-25 per cent, and Ukraine would become the largest beneficiary of CAP funds, due to the size of its agricultural sector.

Under current rules, EU enlargement to all current candidates would increase the CAP budget by 22-25 per cent.

There are multiple ways to reform the CAP to limit its burden on the EU budget: focusing transfers on neediest farmers and limiting those going to large companies; requiring co-financing from member-states; and introducing transition periods for new entrants – though this would lead to very asymmetric transfers between old and new EU members.

But enlargement is not the only challenge facing the CAP: the Commission has pointed to its objective of making the agri-food sector respectful of planetary boundaries, EU climate targets, biodiversity and the quality of soil, water and air. This would require stronger conditionality requirements linked to sustainability for CAP transfers. However, the direction of travel of the Commission seems to be rather the opposite, privileging incentives for sustainable practices as opposed to mandates requiring them across the board, given the former leave more flexibility to farmers than the latter.

Enlargement and EU cohesion policy

As previously mentioned, the accession of current candidate countries would significantly lower the EU’s GDP per capita, increasing economic disparities across new and old member-states. For this reason, cohesion policy will be even more important in years to come. With full-scale enlargement, overall cohesion spending would increase by an estimated 7 per cent: in addition to new entrants starting to receive such funds, transfers to existing member-states would drop.

These distributional shifts are inevitable but the EU should carefully manage them, possibly through a slow phase-out of transfers to regions that would cease to be cohesion beneficiaries and phase-in to new members. It is also important to note that if cohesion transfers remained capped at 2.3 per cent of GDP of the receiving country, as is the case today, new members might end up receiving lower amounts per capita than richer member-states currently do. This calls for revising this arbitrary cap, possibly for a temporary transition period.

Calls for changes to cohesion policy have been numerous in recent years – most recently reshuffling its unspent funds to energy security and rearmament. While drawing on such resources to address emergencies is understandable, the EU should address the causes for low and slow absorption of cohesion funds, simplifying their uptake while preserving their raison d’être – economic development.

A recent expert report on the future of cohesion policy has argued that institutional reforms are just as important for economic development as infrastructure investments. And the Council has highlighted the need for cohesion policy transfers to shift from cost-based transfers that reimburse investments to performance-based transfers that reward achievements. If these changes are indeed integrated into a reformed cohesion policy, its effectiveness in both exisiting and future EU member-states will increase.

Enlargement and EU financial support for climate action

Since the 2014-2020 MFF, the EU has aimed to ‘mainstream’ climate action support across its budget. This has translated into an objective of at least 30 per cent of the EU MFF and 37 per cent of NGEU funds flowing towards climate-relevant activities, though precisely tracking such activities is complex and not fully transparent in today’s budget.

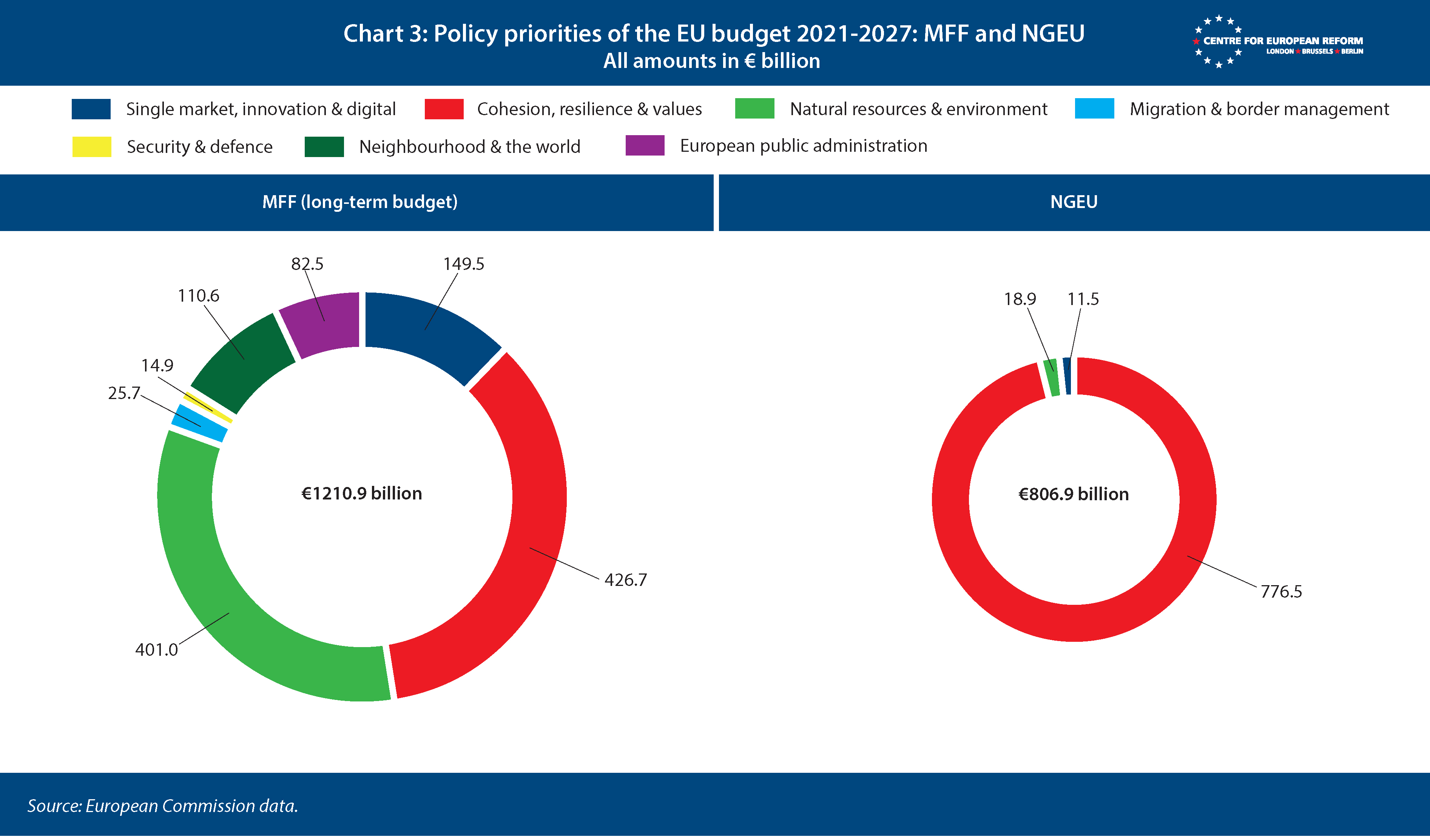

In practice, much of the financial support for climate action and the environment in the EU budget is nested under the ‘Natural resources and environment’ header (see Chart 3), along with CAP funding. Some programmes nested under the ‘Single market’ header are also relevant for climate action, such as Connecting Europe, a programme that supports cross-country infrastructural investment in energy and transport (€31 billion in 2021-2027).

While the implications of enlargement for the CAP have received much attention, the impact of enlargement on support for climate and environment is rather underappreciated. The countries that joined the EU in 2004 then had a more carbon-intensive energy mix than the EU-15 average. The current candidate countries are in a similar position: power production in the Western Balkans was more than three times as carbon intensive as the EU-27 average in 2020. Solid fuels were the main source of primary energy production in 2022 amongst candidate countries, with the exceptions of Moldova, Albania and Ukraine. This implies that support for investing in clean electrification, industrial decarbonisation and grid infrastructure, to name a few, is going to be essential.

This will put additional pressure on EU programmes such as the Just Transition Fund (€17.5 billion over 2021-2027), which supports economic diversification in member-states most negatively affected by the energy transition and by climate action, due to their highly carbon-intensive energy mix and industrial production. Similarly, the Connecting Europe Facility will be critical to boost cross-border infrastructural investments, both in energy and transport.

Beyond enlargement: Imperatives for change in the next EU budget

The possibility of large-scale EU enlargement provides a cogent rationale for reforming the EU budget, rethinking both its resources and spending destinations to ensure its sustainability in a larger Union. But even if enlargement proves to be slower than expected, reforming the EU budget is necessary for the EU-27. The Union cannot afford to tinker with marginal, incremental adaptations to its budget.

As evidenced by the multiple shocks experienced in recent years – from the pandemic to Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis – the EU needs to make its budget more flexible to better respond to crises. Additionally, a collective, co-ordinated response to a crisis that affects all EU member-states can lead to more efficient use of limited fiscal resources – for example, co-ordinating vaccine purchases sped up their distribution during the Covid-19 pandemic, and a joint procurement approach might speed up rearmament. Co-ordination is also necessary for investing in public goods with long time horizons, such as expanding power grids and interconnectors across the EU, especially in poorer member-states with dated, patchy infrastructure – a prerequisite for the energy transition to be socially just across the EU.

The EU budget is slow to adjust to new priorities. The closest thing to an EU budget revolution in recent years has been the implementation of NGEU – but it has repeatedly (though not fully convincingly) been dubbed a one-time experiment by several European leaders.

NGEU has been innovative in at least three ways: its funding source, its funding destinations, and the way funds are disbursed. First, NGEU has been financed through common debt: the bond issuance to finance NGEU is the largest one to date, at €800 billion to be repaid between 2028 and 2058. Second, its funds have been targeted in large part to new policy priorities rather than to the core focus areas of the MFF (agricultural policy and economic cohesion), with a specific focus on accelerating investments for the green and digital transitions. Third, NGEU’s funds – a mix of grants and loans – have been made conditional on member-states meeting several requirements, including the implementation of structural reforms, the timely achievement of investment targets and the respect for the rule of law. These innovations should be integrated into the EU budget at large.

Conclusion

Different simulations of the impacts of EU enlargement on the EU budget dispel the myth that the inclusion of new member-states would bust the budget. Rather, they point to specific policy questions that need to be answered in order to pave the way for enlargement: How should the EU finance increased spending in a larger Union? How should it mitigate the distributional impacts of funds being redirected from current member-states to new ones? How should the key spending programmes in the EU budget be reformed to align with the need to speed development in accession countries and with the multiple competing priorities that the EU budget should support? As the geopolitical context becomes more volatile, how could the EU budget become more flexible to support (more) member-states in responding to external shocks?

Existing member-states should recognise that a unified response to the key investment needs of the 21st century is not only politically urgent but also fiscally savvy: continuing the NGEU’s joint debt approach to funding crucial investments in European public goods such as energy and digital infrastructure can structurally boost competitiveness, and rearmament is best funded collectively as well. Existing programmes can improve too: CAP payments should be better targeted and conditional on sustainable farming practices, and cohesion transfers should be more performance-related and tied to structural reforms and respect for the rule of law. Smoothing changes in distribution from old to new member-states will be key to ensure support for enlargement.

Elisabetta Cornago is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

This article has been supported by the European Climate Foundation. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies with the author. The European Climate Foundation cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained or expressed therein.

Add new comment