Britain's services firms can't defy gravity, alas

Britain's specialism in traded services, some of which can be delivered electronically, has led Brexiters to claim that the country's trade will inevitably unmoor itself from Europe. In fact, Britain is not about to enter a "post-geography trading world".

Trade between two countries is greater if they have larger economies, and less if they are more distant from one another. This observation, underpinning the ‘gravity’ model of trade, has proven itself to be remarkably robust. Evidence from the gravity model undermines the government’s ‘global Britain’ narrative, in that it shows that the EU is the UK’s natural trading partner; that the single market has done more to raise trade in services than free trade agreements (FTAs); and that any barriers thrown up as a consequence of Brexit will be hard to offset with lower barriers to trade with the rest of the world. Yet, after the Brexit vote, gravity has fallen foul of a choir of non-believers. The Brexit Secretary, David Davis, doubts its continued relevance. Nearly half of the UK’s exports are now in services – an unusually high proportion for a medium-sized economy – and Davis contends that cultural links and language, not geographic proximity, will become more important in the future. Liam Fox, the Secretary of State for International Trade, has heralded the post-Brexit opportunities on offer in a “post-geography trading world”. The implication is that the UK’s prowess in services means that distance will become irrelevant.

The UK’s specialism in services does not mean it’s entered a “post-geography trading world”.

When it comes to goods and agriculture, the idea that trade is detached from geography is flat wrong. The rest of the EU is the UK’s biggest trading partner thanks to its size and proximity. Distance reduces trade in goods significantly, although new research suggests distance has become a little less important over time, with the cost of trade imposed by distance falling by 11 per cent between 1986 and 2006.

But it is at least intuitive that distance should matter less in services, and therefore for Britain’s trade, compared to for example Germany, which specialises in manufactured goods. Britain does conduct more trade with countries with which it shares a language than economic size and distance would predict. And services are increasingly delivered electronically, with financial transactions, advertisement mock-ups, and architectural blueprints sent to clients over the internet. The cost of air travel has steadily fallen since the 1960s, making it cheaper to do business across borders. However, this intuition does not show up in the data. The effect of distance on trade in services is similar, if smaller, to its effect on goods: a 10 per cent increase in distance between countries reduces services trade by 7 per cent. That effect has been diminishing over time, as air travel has fallen in price and information and communication technology has improved, but it has not fallen precipitously.

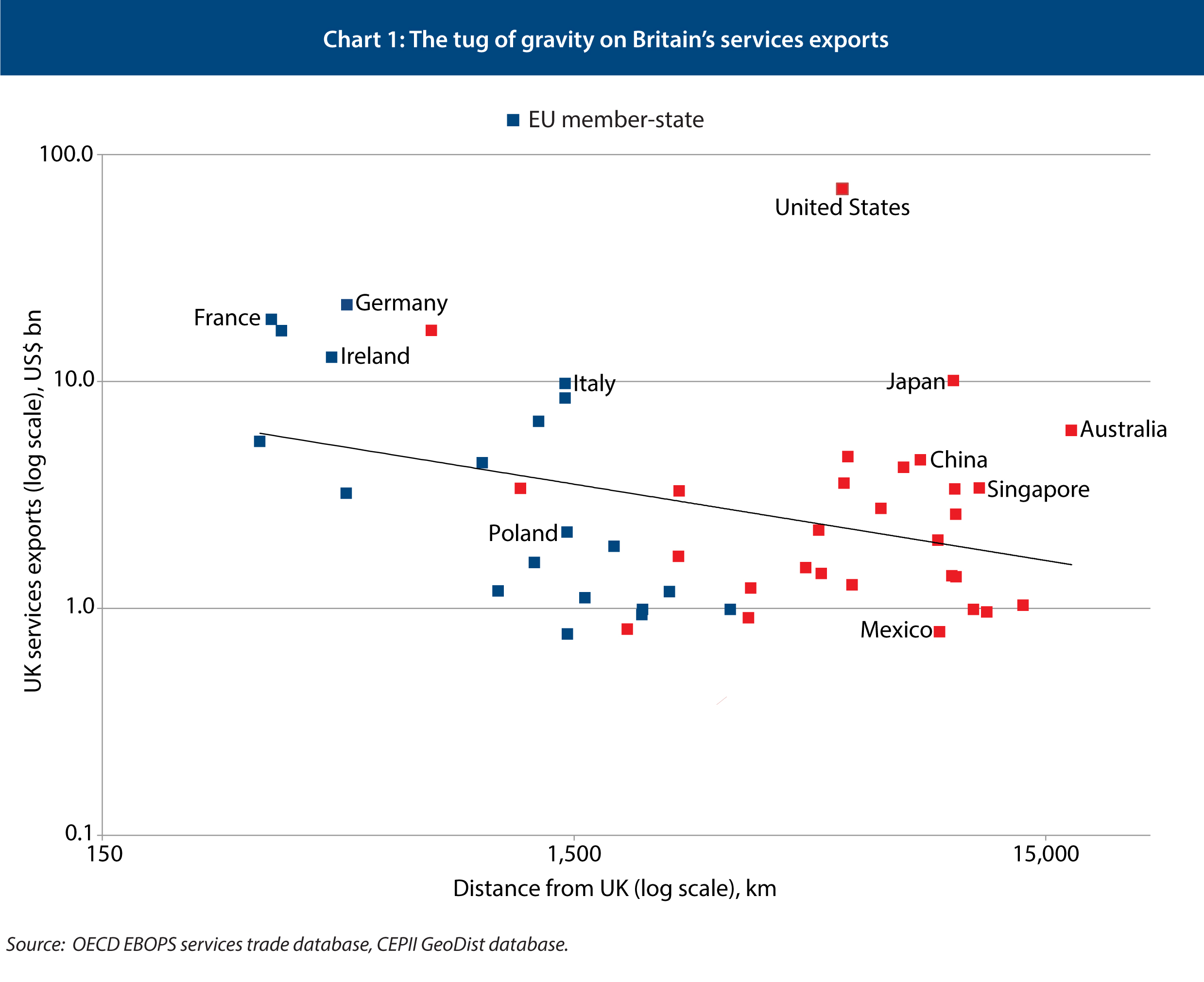

In a rough and ready way, Chart 1 shows the effect of gravity on the UK’s services exports. The US is by far the UK’s biggest individual market, thanks to the huge flows of financial services between the City, New York and other US banking centres. But the EU as a whole is far bigger: consider the case of Italy, which buys a similar amount of Britain’s services as Japan, despite Japan’s economy being 2.5 times larger. And richer countries tend to buy Britain’s services exports more than poorer ones: Australia buys six times more from UK services firms than Mexico does, although their economies are around the same size. (While countries that speak English do tend to trade more with the UK, the effect is not that big.)

The EU is a rich, large market that is on the UK’s doorstep, and its single market has proved more effective at reducing barriers to services trade than bilateral free trade agreements. The EU’s rules have led to an estimated 60 per cent boost to services trade between EU member-states, while FTAs have had no discernible effect. This suggests that Brexit will cut UK services trade with the EU enormously, unless the UK stays in the European Economic Area.

Distance matters for two reasons. First, just as it costs more to ship a Rolls-Royce aeroplane engine to Tokyo than to Rotterdam, there are costs to supplying services from afar. Second, the increasing interdependence of services and goods finds them bound, both through practicality and policy, to the same geography as traditional manufacturing supply chains. And even if distance did not matter, services liberalisation is notoriously tricky and there is little reason to think the UK alone will find more success breaking open new services markets than it has done as a member of the EU.

Services are largely delivered by people. While technology has certainly made interactions at a distance easier, these interactions still often require both parties to be in the same place: for either the customer to go to the supplier, or the supplier to the customer. This comes with in-built constraints. More people from the UK go on holiday to Spain than to South Africa as it is much nearer and cheaper to fly to. Equally, while technology such as Skype has allowed, say, an IT consultant to work on a project in the UK while based in the US, there are still benefits to be gained from meeting a partner in person at some point. Again, distance and cost come into play.

While being able to speak the same language as the person you are providing a service to is certainly important, so is being awake. The UK is fairly well situated to this regard – London-based financial institutions currently service Asian markets in the morning and American markets in the afternoon – but it is not immune to the tyranny of time zones.

Of increasing importance, and currently under-discussed in the Brexit debate, is the fact that goods are often no longer just goods. Products and services are increasingly bundled together as one, a phenomena sometimes referred to as services in a box, or Mode 5. As such, services inputs, for example consulting and design services, often account for a significant amount of the value – estimates range from 20 to 47 per cent across all sectors – embodied within a manufactured product, such as a Rolls-Royce ship engine that is remotely monitored and serviced through the use of onboard sensors. Ingo Borchert and Nicolo Tamberi, writing for the UK Trade Policy Observatory, “find that domestic services value added embodied in [Britain’s] manufacturing exports is worth more than £50 billion per year, roughly the same amount as all financial services exports.”

Ignoring the contribution of embedded services to UK goods exports risks underplaying the degree to which the UK services sector is dependent on pan-European manufacturing supply chains. These undercover services exporters are bound to the proximity of manufacturing bases both as a result of convenience and policy.

The convenience point speaks for itself. For all the reasons given above, when employing a PR consultant to boost demand for your wi-fi enabled teddy bear, for example, the ability to meet in person and be assured that they know the regional market well remains important.

But trade policy plays its part. In order to qualify for a free trade agreement, an exporter must be able to demonstrate that a sufficient amount of the value of the product they are selling was realised within the territory of a party to the agreement. For example, for a European car exporter to qualify for tariff-free treatment under the EU-South Korea free trade agreement, they must be able to show that 55 per cent or more of the car’s value originates within the EU. This can be complicated in and of itself. Accounting for the value-added input of services makes it more so. While software can usually be traded across a border without attracting a tariff, once embodied within, say, a car, the added value it creates might need to be taken into account for the purpose of assessing whether the car qualifies for the free trade agreement, or not.

#Brexit ministers argue UK services exports will soar, unconstrained by gravity. Reality will bring us crashing down to earth.

Doing so is not something exporters or customs officials find easy. Current WTO rules on customs valuations are technologically outdated and do not cover, for example, embedded software. While there have been some moves to make them fit for the 21st century, largely driven by the EU, progress has been slow. In practice, as the rules are modernised and mode 5 services are properly accounted for, they will likely become even more geographically restrictive, not less (see recent suggested changes to NAFTA, for example). This means that, when relying on domestic services inputs to qualify for a trade agreement, there is increasingly little room for ambiguity as to where the services inputs are from. Again, services find themselves bound to the physical geography of manufactured goods.

Reports of gravity’s death have been greatly exaggerated. Even were that not the case, post-Brexit, the UK will find opening up new markets for its services exporters difficult. Multilateral services liberalisation has struggled to progress beyond the commitments made during the 1995 WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services. At a bilateral and regional level (with the EU the notable exception) it has fared little better. Regulatory barriers abound, and, as the EU discovered when negotiating a trade agreement with India, talks of services liberalisation quickly becomes tied to politically challenging demands on the movement of people and business visas.

The idea that globalisation has become unmoored from geography – and Britain is about to reap the rewards – is wishful thinking. The evidence points to the opposite conclusion: Brexit will damage the UK’s flagship services sector, rather than liberating it.

John Springford is deputy director and Sam Lowe is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty correctly used would have made the Referendum question:

“Remain a member of the European Union”, or

“Notify the European council of the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the European Union."

The current mess can only get worse, by the UK also not respecting the principle, of the sovereignty of the people.

When a country's electorate decide to leave an organisation, a government believing in democracy, just cannot allow that country to be a member of that organisation, 20 months after the voting.

To do this and to undertake the most serious political and economic change of the last forty years on this basis is pretty serious.

No democracy can exist, unless the alternatives the electorate vote on, can be delivered when the votes have been counted.

The only 2 honourable ways forward are:

1. Have the EU Referendum annulled, because it was unlawful, illogical and undemocratic, or

2. Leave the EU, which is an organisation, as per the vote in the 2016 Referendum, and become like Norway, Switzerland and Iceland

Both of these require the UK to honour its Lisbon Treaty obligations, which like all EU Treaties have been ratified by the UK Parliament.

This year is 100 years since WW1 finished. Millions died, but from the ashes, including WW2 and the Balkans, the UK created the Europe with its 28 plus countries, and the borders they now have. Without the UK there would have been less than 8.

All the other EU countries consider themselves sovereign, independent, democratic and lawful.

Why therefore does the UK consider themselves not sovereign and independent, and why do they have to be undemocratic and unlawful, to demonstrate this?

Add new comment