Brexit, four years on: Answers to two trade paradoxes

Since the UK left the EU in 2020, its goods exports to the EU have not performed any worse than to the rest of the world, and its services exports have grown strongly. How come?

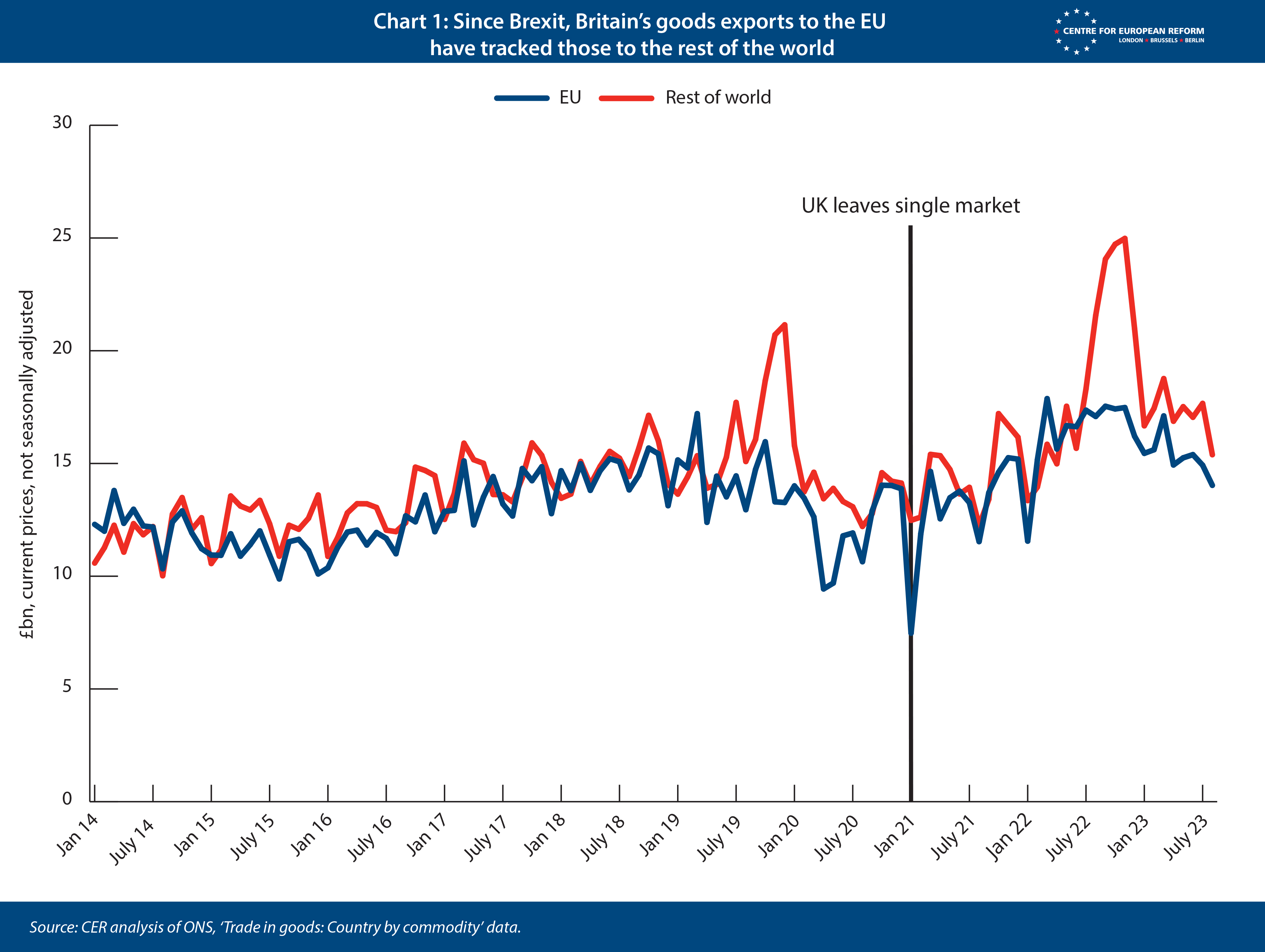

Headline UK trade numbers have been surprisingly robust after Brexit. Goods exports to the EU have tracked those to the rest of the world, despite new trade barriers being imposed on the former but not on the latter (Chart 1). And services exports to both the EU and the rest of the world have been growing at a decent clip since the UK left the single market.

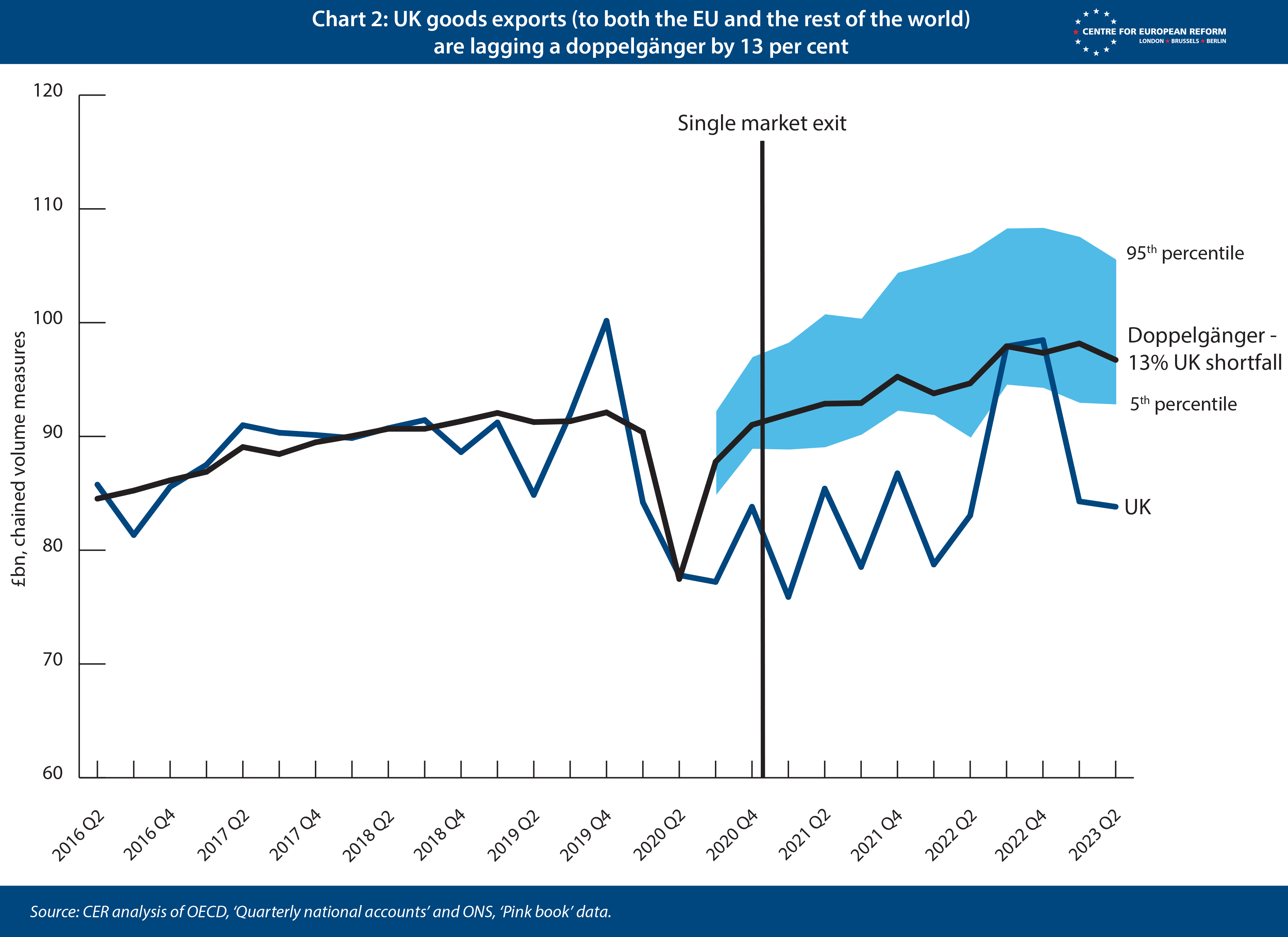

On the other hand, a ‘doppelgänger’-type analysis of UK goods trade shows a significant shortfall against a statistically-derived economy that closely tracked UK goods trade to January 2021, when the country left the single market and customs union. According to this measure, widely used in social science to quantify the effects of policy changes, UK goods exports are 13 per cent lower as a result of Brexit (Chart 2).

The doppelgänger analysis suggests that UK goods exports have been curtailed by leaving the EU. But one would expect the damage to be showing up most strongly in UK exports to the EU, which has imposed the full panoply of checks on British goods entering the Union (Britain is yet to do the same to EU goods entering its territory). The fact that UK goods exports to the EU have performed on par with exports to the rest of the world therefore requires explanation.

The other paradox concerns services exports. Modelling conducted before Brexit estimated that UK services exports would fall by 14 per cent if Britain left the EU. But services exports have, at first sight, fared well since the UK left, growing faster than the G7 average since 2021. It is worth remembering that the consensus estimates of the overall impact of Brexit on GDP – a long-run reduction of 4-5 per cent compared to a Britain that remained in the EU – are predicated on a 10-15 per cent hit to trade in both goods and services. But we are not seeing a big enough hit to trade, at least in the headline figures, to justify those estimated GDP losses. What is going on?

An answer to the goods paradox

My initial answer to the goods paradox, published in March 2022, was based on intuition. Comparing UK exports to the EU with those to the rest of the world makes sense only if Britain’s sales outside Europe are unaffected by Brexit. But my hypothesis was that wasn’t necessarily the case: the EU has very complex supply chains, with components being made in one country and put into goods in others, to then be sold both within Europe and globally. So the UK could have been cut out of European supply chains as a result of Brexit, which would mean that it was importing fewer components from the EU and selling fewer goods to both the EU and the rest of the world. It turns out that the answer is somewhat different.

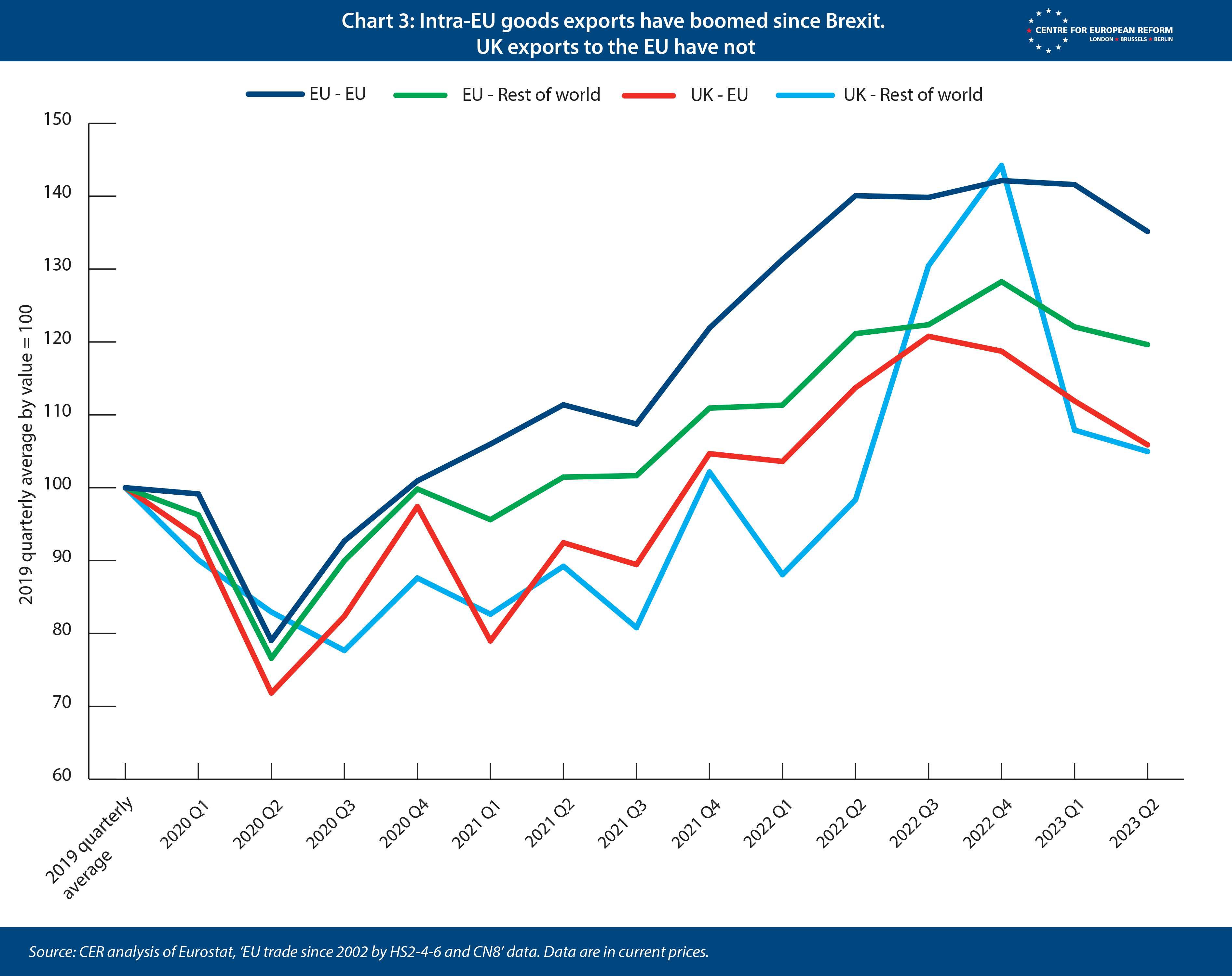

We need to take into account that, after Covid lockdowns were lifted, intra-EU exports grew much faster than exports from Europe to the rest of the world. Chart 3 shows EU member-states’ goods exports, broken down into exports sold to other member-states and those to the rest of the world. Over the course of 2021 and 2022 the value of intra-EU exports grew much faster than those to the rest of the world, but the UK did not join in the trade boom in European goods. Brexit is almost certainly to blame for that.

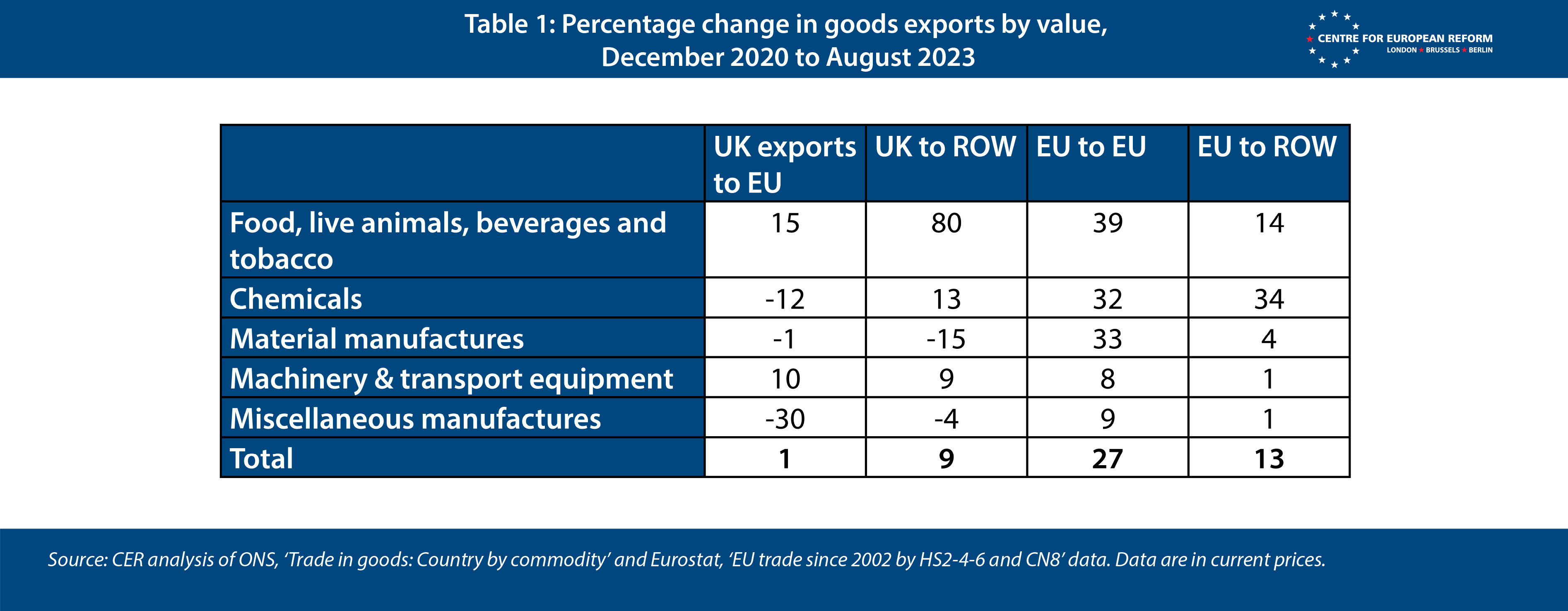

The difference between EU rebound and UK stagnation was especially apparent in food, beverages and tobacco, chemicals and material manufactures (such as things made out of plastic, stone or rubber), and it was common across UK exports to most EU member-states. The UK missed out on a big rise in European trade as a result of the border costs that Brexit imposed.

Take miscellaneous manufactures, which include an array of items like medical equipment and supplies, jewellery, sporting goods, toys and office supplies – the type of goods produced by medium and small firms that have struggled the most with the border costs imposed by Brexit. UK exports in this category to the EU declined by a staggering 30 per cent, while EU-to-EU trade grew by a healthy 9 per cent.

If Britain’s total exports to the EU had grown in line with those of EU member-states, they would have been 27 per cent higher than they were in August 2023 (the last month for which we have comparable data). Since exports to the EU make up around half of Britain’s total, this suggests its total goods exports are around 13.5 per cent down, or £13.4 billion on a quarterly basis. That is close to what is needed to generate the 4-5 per cent reduction in GDP (and very similar to the doppelgänger estimate). In other words, if the UK had remained a member of the EU, its exports to the EU would have probably outpaced those to the rest of the world. The fact that EU and non-EU exports moved together is a sign of weakness, not robustness, and is a direct consequence of Brexit.

An answer to the services paradox

For the 4-5 per cent Brexit hit to GDP to continue to be our central estimate, there must also be a sizeable shortfall in services trade. The UK is unusual for a large economy because services make up a big share of its total trade – almost half. If services trade performs better than the assumptions that were put into the Brexit models, there’s a problem.

How, then, can we account for the strong UK services export growth compared to the G7 average? The answer is – again – that it is important to consider the right counterfactual. If we account for rising demand for services exports, we see that British exports should have performed even better than they did.

Chart 4 plots how UK services exports have fared compared to 22 economies that are the most mature globally (these are the economies that the IMF designated as ‘advanced’ in 1995). Telecoms and IT, insurance, pension, and ‘other business services’ – a series that contains consultancy, accounting, legal services – have all grown faster in the UK than the average of advanced economies since the UK left the EU. Two services sectors have not, however. The first is financial services, which has grown more weakly in the UK than elsewhere since the start of 2020 – when many financial services companies based in the UK started setting up operations in the EU. The other is transport services – a category that contains road haulage and shipping. Like financial services, growth in British exports of transport services are well down on other advanced economies, despite full reopening of the economy. That is probably because Britain’s goods exports to the EU have been hit, reducing demand for British lorry drivers’ services. Also, they can no longer do ‘cabotage’ within the EU – moving goods between member-states.

It is not surprising that shortfalls in services exports show up in these two sectors, because they are those in which the EU’s single market is most developed and there are big barriers to EU market access for countries outside the bloc. In finance, any regulated financial institution can sell services to a customer in another member-state. And in transport services, there are strict rules that prevent EU member-states from discriminating against each others’ logistics companies. After leaving the EU, UK-based companies in these sectors faced significantly larger barriers to exporting. Other sectors, such as consulting, accountancy, telecoms and IT can more easily sell in the EU despite Britain having left.

If the UK’s exports in these two sectors had performed in line with the global average of advanced economies from single market exit to the second quarter of 2023, then Britain’s total services exports would have been 11 per cent, or £10 billion higher in that quarter. Again, that’s broadly in line with the 4-5 per cent hit to GDP.

Conclusions

The solution to the UK’s export paradoxes, then, is to pick the right counterfactual. Intra-EU goods trade boomed over the last few years, outstripping Europe’s exports to the rest of the world. As a non-member, the UK’s goods trade missed out on that boom. Similarly, after leaving the EU, UK-based services companies faced significantly larger barriers to exporting to the EU in areas where the single market is advanced like transport and financial services. In those sectors, Britain’s export growth languishes behind other advanced economies. So, if the UK had remained an EU member, its services exports would probably have grown much faster.

Taken together, the missed growth in goods and services trade account for about a £23 billion quarterly hit to UK exports, which is consistent with a GDP reduction of 4-5 per cent compared to a Britain that had remained. Paradoxes resolved.

John Springford is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Add new comment