UK should work more closely with MEPs on Brexit

There is a long and colourful history of European politicians saying one thing in Brussels only to go home and tell their domestic audience the complete opposite.

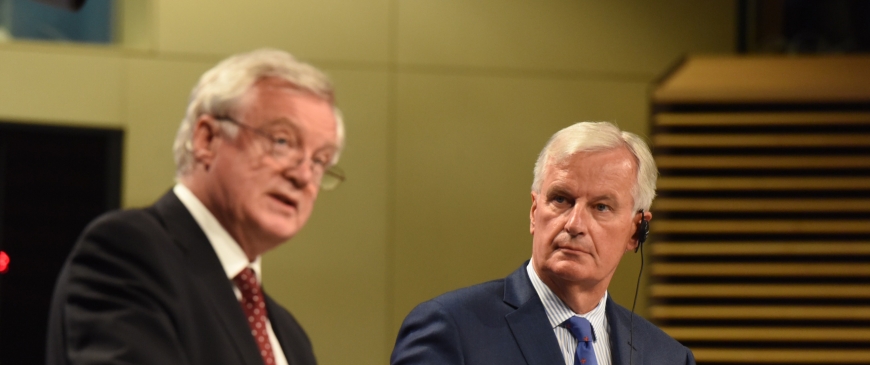

David Davis has learned the hard way that when it comes to Brexit, it's best to stick to the original script or he risks damaging the UK's negotiating position.

Davis got into trouble when he said that the hard-fought agreement between prime minister Theresa May and the Commission's task force to move the Brexit talks onto the future bilateral relationship was merely a "statement of intent".

But something positive might have emerged from this – Davis now says he is keen to work more closely with the European Parliament.

Strictly speaking David Davis was correct – the deal will remain a gentleman's agreement until it is translated into a legal text. But his flippant statement put noses out of joint in Brussels.

Guy Verhofstadt, the parliament's point man for Brexit, accused Davis of undermining mutual trust. And the comment prompted the parliament to toughen its stance and insist that the Brexit talks can progress during the second phase only if the British government fully respect its commitments.

Davis responded on Twitter that he had spoken "to my friend" Verhofstadt, and that he was committed to turning the EU-UK agreement into a legal text as soon as possible.

Then came the silver lining: Davis tweeted that he looked forward to working closely with the parliament on the next phase of the Brexit talks, especially on citizens' rights.

Wise move

This is a wise move. The European parliament does not have formal powers to negotiate with the British alongside Michel Barnier. But it can veto the UK's withdrawal agreement as well as any deal on its future relations with the EU-27. There's no indication that it might use that power, which would result in the UK crashing out the EU without a deal, but it has skin in the game.

MEPs have flexed muscles before in order to extract concessions from the commission and member states.

In 2010, MEPs torpedoed for example an agreement between the EU and the US on the processing and transfer of financial data for the purposes of terrorist finance tracking. It would help the UK's negotiators to treat the European parliament seriously.

Brexiteers have tended to overlook the role of the European parliament both in the Brexit process and in the past. The body made up of 751 members of the European parliament (MEPs) elected by EU citizens has for years been ridiculed in the UK for being little more than an expensive talking shop.

The parliament's shuffling between plenary sessions in Brussels and Strasbourg has become a well-worn metaphor for the largesse and absurdity of European institutions. Most Britons have little idea what the European parliament really does. News coverage has been largely negative, from criticism of MEPs generous salaries, or more recently, when eurosceptic parliamentarians from the UK Independence Party had a physical altercation which left one in hospital.

Follow Barnier's lead

True, the European parliament is not perfect. It has pushed for larger EU budgets at a time when several member states were being forced to cut their spending. But it has also done many commendable things; it has fought relentlessly to improve consumer rights, launching for example an inquiry into the Volkswagen emission scandal. On Brexit, MEPs helped to make citizens' rights one of the priorities of the early phase of the negotiations.

The EU's chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, understood early on that it is important to have the European parliament on side to ensure that the Brexit negotiations go smoothly. He has regular meetings with MEPs, takes the parliament's views into account ahead of the negotiating rounds with Davis and debriefs MEPs afterwards.

The British government should follow Barnier's lead and step up engagement with the European Parliament. Theresa May has met some high profile MEPs but she has been reluctant to address the plenary. But if the UK wants to strike an ambitious agreement on the future relations with the EU-27 it needs to make a case for it not only in member-states or Berlaymont but also in the European Parliament.

Davis has joked that he doesn't have to be clever to do his job, or to know very much. But when it comes to engaging with the European parliament on Britain's withdrawal from the bloc, he looks to have made a wise call. Britain stands to benefit if he can now follow through on his statement of intent

Agata Gostynska-Jakubowska is senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.