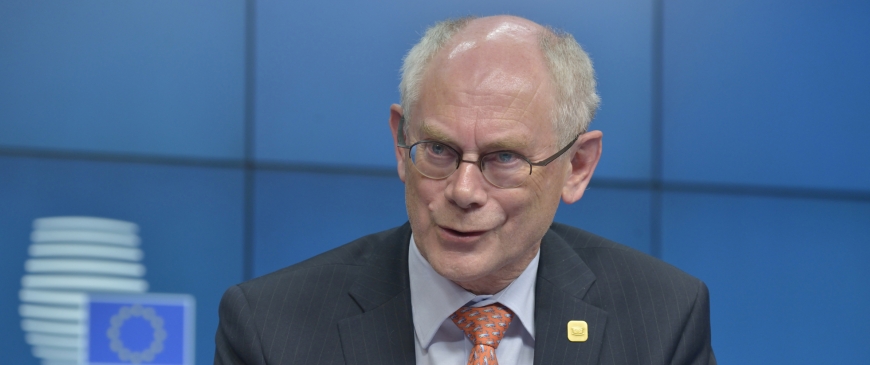

Herman’s handbook for the new Council President

Despite a reputation for having the “charisma of a damp rag”, as Nigel Farage once put it, Van Rompuy made European Council meetings more efficient and his successor should learn a lot from him, writes Agata Gostyńska.

On Saturday, EU leaders will reconvene to decide on the remaining top EU posts. Another round of political squabbles is unacceptable. It would damage Europe’s credibility; something that the EU, beset by economic stagnation and international crisis in its neighbourhood cannot afford. Forging a consensus on the High Representative and President of the European Council is thus a pressing issue. If Herman Van Rompuy can reconcile competing demands for geographical, political and gender balance, it would be the cherry on the cake of his presidency. But he should focus on the qualities needed to do the job more than the political demands of EU leaders. He could do much worse than seek a successor with some of his own best characteristics.

Van Rompuy’s successor does not need charisma to be an efficient chairman and honest broker. Despite a reputation for having the “charisma of a damp rag”, as Nigel Farage once put it, Van Rompuy made European Council meetings more efficient. He used concise conclusions to set out a strategic direction for the EU. The strategic agenda which EU leaders endorsed in June is a case in point. But Van Rompuy’s job was mostly about forging consensus among the EU leaders on matters such as eurozone governance or treaty revision. Van Rompuy knows that this is a balancing act which requires the president to keep his personal ambitions in check. Though Van Rompuy can hardly be blamed, he was in charge when the British blocked treaty change in December 2011 to introduce stricter budgetary discipline on member-states’ budgets: David Cameron simply would not compromise. This illustrates that a European Council president will have to deal with failures he cannot be blamed for and broker deals without claiming credit for them.

The European Council president should be sensitive to concerns of member-states that are not in the eurozone. The sovereign debt crisis has elevated the European Council to the primary forum for the discussions on the Economic and Monetary Union. But it also accelerated cooperation among the eurozone members. Van Rompuy became more sensitive over time towards the concerns of both euro ‘outs’ and ‘pre-ins’. A new president should also be able to reconcile the pressing need to deepen the euro cooperation with the vital interests of the ‘pre-ins’ in the long term arrangements in the eurozone.

Anyone with strong views on either side of the stimulus debate will not get the President’s job. The eurozone is suffering from economic malaise. This means the debate on ways to provide economic stimulus will remain the number one priority to be debated at the level of the EU leaders. They will favour a contender who is moderate on the macroeconomics; something which could help to bridge disagreements on eurozone matters.

Van Rompuy’s successor should be assertive towards the European Parliament. Van Rompuy understood the importance of nurturing relations with MEPs but he avoided setting any precedents which might give them even more power. Now that the Spitzenkandidaten process has been effectively put into practice, the European Parliament is hungry for more influence. But it is a bad time for a Parliament that suffers from its own legitimacy problems to demand this. The new president should rather champion a debate on how to plug national parliaments better into EU policy-making.

Finally, Van Rompuy’s successor should have a good understanding of the dynamics of Britain’s engagement with Europe. Should the UK seek a renegotiation of its membership after the next general election, in May 2015, the European Council will be the primary forum for deciding whether to revise the EU treaties and consider Cameron’s wish list of reforms. If this is the case, the new president will have to look for common ground between the UK, and other member-states, to accommodate the British concerns.

For the last week, the media have been speculating about possible contenders. Donald Tusk (Poland), Helle Thorning-Schmidt (Denmark), Valdis Dombrovskis (former Latvian prime minister), Andrus Ansip (former Estonian prime minister) and Enda Kenny (Ireland) have been most often mentioned as those who would fill the bill. But Dombrovskis and Ansip have been nominated by their countries to be Commissioners. Both could still emerge as late compromise candidates. But if they were offered a substantial Commission portfolio, both the Latvian and Estonian former prime ministers might hesitate to swap the Berlaymont for the European Council premises.

This leaves Tusk and Thorning-Schmidt as frontrunners. Tusk’s advantage is that Poland is committed to adopting the euro in the future, whereas Denmark has a permanent opt-out. His appointment would recognise the economic and political progress of the Central European countries since joining the EU. But the Nordic countries have not held the EU top post either. None of the European Commission’s presidents have come from Denmark, Sweden or Finland. Thorning-Schmidt as a former MEP would also probably know better how to manage the relationship with the European Parliament.

What is likely to tip the balance between Tusk and Thorning-Schmidt is Germany’s support. Angela Merkel enjoys friendly relations with both leaders, but this might be of minor relevance here. What seems to matter more is that Germany opposes the French taking up the Economic and Monetary Affairs portfolio in the Juncker College. Germany may be willing to concede both remaining top EU jobs to the Party of European Socialists in exchange for a Commissioner with more hawkish views on eurozone policies.

Be it Tusk or Thorning–Schmidt, Van Rompuy will still have to secure unanimous support for either of them. The EU treaties allow a vote on the European Council president, but leaders will probably resist this. A lack of unity would damage contenders’ credibility at home and in Brussels, a risk that active politicians are unwilling to take. So brokering a consensus among the 28 over his successor is likely to be the final and biggest test for Van Rompuy’s conciliation skills.

Agata Gostyńska is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform in London.

The longer version of this article was published first by the Centre for European Reform on 21 August.