Debunking Jacob Rees-Mogg’s claim an extension period will make the UK a ‘vassal state’

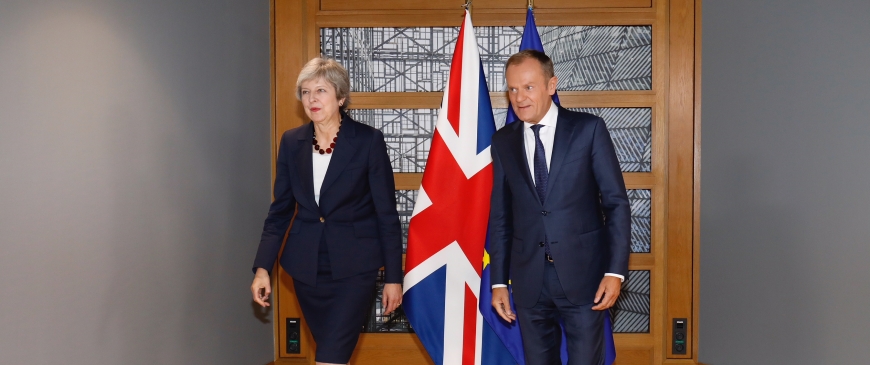

In an effort to break the Brexit negotiation deadlock over the Irish backstop, it is reported that Theresa May has conceded that the standstill transition period could be extended beyond its current deadline of December 2020. This would keep the UK fully economically aligned with the EU, but without voting rights. This has led to criticism from members of the Conservative party on both sides of the Brexit debate. Jacob Rees-Mogg is fond of saying that the UK will become a subservient, “vassal state”.

However, whether it helps deal with Ireland or not (a question requiring its own dedicated piece), inserting an option to extend the transition period into the withdrawal agreement was always needed and is eminently sensible.

It has been largely missed in the domestic Brexit debate, but the reality is that – assuming the withdrawal agreement is signed – the UK will leave the EU without having certainty over the future relationship. The political declaration on the future relationship, which will accompany the withdrawal agreement, will not legally bind either the EU or UK to a specific outcome, and in all likelihood will be vague with regards to the future relationship, leaving multiple options on the table.

And while it is theoretically possible that the future relationship could be hashed during the 20 month transition period (comparisons with previous EU trade negotiations, which took much longer, don’t quite read over, as we should assume a higher frequency of negotiation rounds in this case), it seems unlikely when you consider that the UK is probably going to spend at least the first six months post-Brexit fighting with itself about what it actually wants, again.

As long as it needs

There are also constraints on the EU’s capacity to negotiate in the immediate aftermath of Brexit – it will be going through its own democratic upheaval with a new European Parliament and Commission to elect and bed in.

Even if it were possible to negotiate the entire future relationship – not just trade, but other areas of cooperation including the overarching governance framework – in 20 months, the EU and UK would probably still need more time to allow for implementation.

An extension could also allow the UK more time to replace all of the third country free trade agreements and treaties it is currently party to via the EU, if necessary.

A (relatively) sensible approach to Brexit would see the process take as long as it needs to, and avoid a dramatic rupture at all cost. Unfortunately some in the UK seem to revel in the idea of hurtling headfirst into the abyss. But their arguments against possible transition extension do not hold water.

Cost has to be weighed against risk and panic

Faux-concern about the additional cost to the taxpayer of transition extension, which would inevitably require the UK continue budgetary contributions to the EU, are facile. Membership of the EU’s internal market is of net benefit to the UK taxpayer, and another few months or years would continue to be so. While you can certainly argue that prolonging the period of uncertainty will have an economic cost – and indeed, uncertainty appears to already be depressing British growth – in this case it has to be weighed against the risk and panic associated with coming up against yet another immovable deadline without an agreement in place and ready to go.

Talk of transition extension being Remain by the backdoor, or an EU plot to keep the UK in the EU, is equally nonsensical. So long as the Article 50 process concludes in March, the UK will have left the EU. And that’s all there is to it.

There is no conceivable reason for the UK to want to construct another Article 50-esque cliff edge to potentially fall off in 2020, especially knowing as it does now that time pressure plays into the EU’s hand. Including an option to extend the transition is not a betrayal, it is not an EU-Remainer conspiracy to reverse Brexit – it is a safeguard any government claiming a modicum of responsibility should be considering.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.