Rethinking the EU's approach towards its southern neighbours

- The EU’s stated objective is to promote prosperity, stability and security in neighbouring countries in the Middle East and North Africa. But in practice, it has had little success on all three counts. The EU’s southern neighbours remain stuck in a middle-income trap, and many are more unstable than they were ten years ago.

- The EU increasingly sees the region as a source of migrants and terrorism, and its approach has been dominated by short-term concerns. But a narrow and unambitious approach does not serve the Union’s long-term interests, as it does little to foster real stability amongst its neighbours.

- The EU’s political and economic offer to its neighbours is measly, and fails to incentivise either closer co-operation or reforms. North African and Middle Eastern neighbours are not offered the chance of becoming EU members and support is limited to financial assistance and a modest upgrade of trade ties. Additionally, the EU’s approach has not been strategic: the Union has provided relatively little support to neighbours like Tunisia, where efforts to promote reform stood a good chance of being successful, while providing substantial unconditional economic assistance to authoritarian regimes such as Egypt.

- The EU has also made little effort to foster regional security. Europeans have been sidelined in the Syrian conflict, and now also in Libya. Member-states have often been divided, making a common European response impossible. At the same time, other actors, such as China, the Gulf states, Iran, Russia and Turkey have gained influence at the EU’s expense. Libya now risks being partitioned between Turkish and Russian spheres of influence.

- The COVID-19 pandemic will deal a heavy blow to many of the EU’s southern neighbours, making a strategic rethink of the EU’s approach even more urgent. While most of the southern neighbours have not yet been severely hit by the pandemic itself, they will suffer from its economic fallout: unemployment and social strife will fuel instability, migration towards Europe and possibly conflict.

- Europe will need to help its neighbours deal with COVID-19 and its economic fallout. But the EU should not lose sight of the long-term picture. If Europeans want their neighbourhood to be stable, they need to take more responsibility for its security. They should, for example, be much more proactive in Libya, agreeing on a common strategy, trying to obtain a ceasefire and providing troops for a peacekeeping mission once a ceasefire is struck.

- The EU should make the countries in its southern neighbourhood a more ambitious offer: deeper market access, more opportunities for their citizens to work in Europe and more financial and technical assistance. The EU should also develop an associate membership model for democratic countries in the region that would be eligible for membership were it not for their geographic location. At the same time, the Union should target its financial assistance more strategically, pushing countries to respect human rights and align with its foreign policy goals, and reducing support if they refuse.

The Arab Spring uprisings of 2010-11 sparked hopes amongst many Europeans that their neighbours in the Middle East and North Africa were on their way to becoming more democratic, prosperous and stable. Almost ten years on, these hopes have largely evaporated. With a few exceptions, notably Tunisia, the EU’s southern neighbours are no more democratic than they were prior to 2011. Moreover, many countries in the region are more unstable than ten years ago, and they are seen in Europe as a source of unwanted migrants and terrorism.

Civil wars have been raging in Syria since 2011 and Libya since 2014. Terrorist groups, such as the so-called Islamic State (IS), have proliferated amidst war, social discontent and poverty. Europe’s perception of its southern neighbours as a source of instability was heightened by the 2015-16 migration crisis, which resulted in over one million people entering the EU. This crisis contributed to the UK’s vote for Brexit, fuelled the rise of populist anti-immigration forces across Europe and deepened political divisions between member-states.

The COVID-19 pandemic will deal another heavy blow to the EU’s southern neighbours, many of whom have weak health systems and lack the financial means to prevent damage to their economies. Unemployment is rising, and governments will be pushed to cut spending further or raise taxes. Economic disruption will fuel further social discontent and extremism, leading to increased migration towards Europe.

This policy brief highlights the failings in the EU’s approach towards its southern neighbours in North Africa and the Middle East. It focuses on the southern members of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), the main instrument of EU policy towards its neighbours. These are Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Syria (Map 1). The brief sets out recommendations for how the EU can reshape its policy to make the region more secure, prosperous and democratic.

The evolution of the EU’s approach towards its southern neighbours

The ENP was launched in 2004 following the EU’s eastern enlargement, and included both the EU’s ‘old’ neighbours to the south and the ‘new’ ones in the east. The ENP aimed to avoid creating new dividing lines between the EU and its new neighbours. In the words of then European Commission President Romano Prodi, the neighbours would share “everything but institutions” with the Union.

The ENP aimed to foster far-reaching change in the EU’s neighbours, gradually turning them into prosperous and stable democracies. The policy was modelled on the EU’s accession process, with objectives agreed between the EU and its partners, and regular reports assessing progress in political and economic reforms. Conditionality was a key element: in exchange for democratic and economic reforms, the EU promised its neighbours greater financial support, market access, and easier travel for their citizens to work, study and visit the Union. While the ENP stressed democracy promotion, in practice the Union emphasised economic liberalisation and did not consistently apply democratic conditionality. The EU forged partnerships with authoritarian states such as Hosni Mubarak’s regime in Egypt and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s in Tunisia, especially after the September 11th 2001 attacks in the US when these governments were perceived to be key allies against international terrorism. In 2008 the EU even began negotiating a trade agreement with Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya.

The ENP aimed to foster far-reaching change in the EU’s neighbours, gradually turning them into prosperous and stable democracies.

In 2008, the EU launched the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) within the ENP framework. The UfM, a French initiative by then President Nicolas Sarkozy, was a revamp of the 1995 Barcelona Process, also known as the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership. The Process was designed to promote regional co-operation in the political, security, economic and cultural fields. The UfM was supposed to complement the bilateral ENP with a multilateral dimension, promoting economic integration between the EU and its neighbours, and between the neighbours themselves, through highly visible regional projects such as infrastructure projects. However, the UfM was plagued by the same issues that had led to the failure of the Barcelona Process: it lacked serious political backing and was hobbled by a lack of co-operation between Israel and the Arab states.

With the 2011 Arab Spring, the EU recognised that its policy had often strengthened authoritarian rulers at the expense of democratic reforms and respect for human rights. The EU carried out a review of the ENP, reorienting it towards greater conditionality in an effort to promote “deep and sustainable democracy” amongst its neighbours.1 Countries that made progress in consolidating democracy and the rule of law would receive greater European support. At the same time, the EU would reduce support to countries that were backtracking on democracy and violating human rights.

The EU did take some steps to promote democracy, for example creating a ‘European Endowment for Democracy’ to support grassroots pro-democracy groups in the southern and eastern neighbourhoods. But in practice, the EU’s approach did not change significantly. Its promise of greater support in exchange for reforms did not yield results. And the Union continually failed to apply conditionality in a rigorous way: instead it continued to co-operate and seek deeper ties with countries that slid back towards authoritarianism, such as Egypt, where a military coup overthrew the democratically elected government in 2013.

In 2015, the EU’s approach changed again. Faced with conflicts in Syria, Libya and Ukraine, Europe’s overriding aim became containing instability. The EU reformed the ENP once more, refocusing it to promote stability, rather than democracy and human rights. The EU’s new approach also promised more differentiation between partners, with ‘priorities’ to be agreed with each country. This marked a recognition that the EU’s previous focus on ‘deep’ transformation had been unsuccessful, that there were limits to the Union’s leverage, and that many neighbours wanted neither closer relations with the EU nor to undertake the difficult reforms necessary to boost their trade with the Union. The trend towards prioritising stability was reinforced by the EU’s 2016 Global Strategy, which focused on fostering ‘resilience’ amongst the EU’s neighbours. While resilience entailed the promotion of human rights and, in the long-term, democratisation, the strategy’s emphasis in the short-term was on promoting stability.

The EU’s policy towards its southern neighbours after the Arab Spring

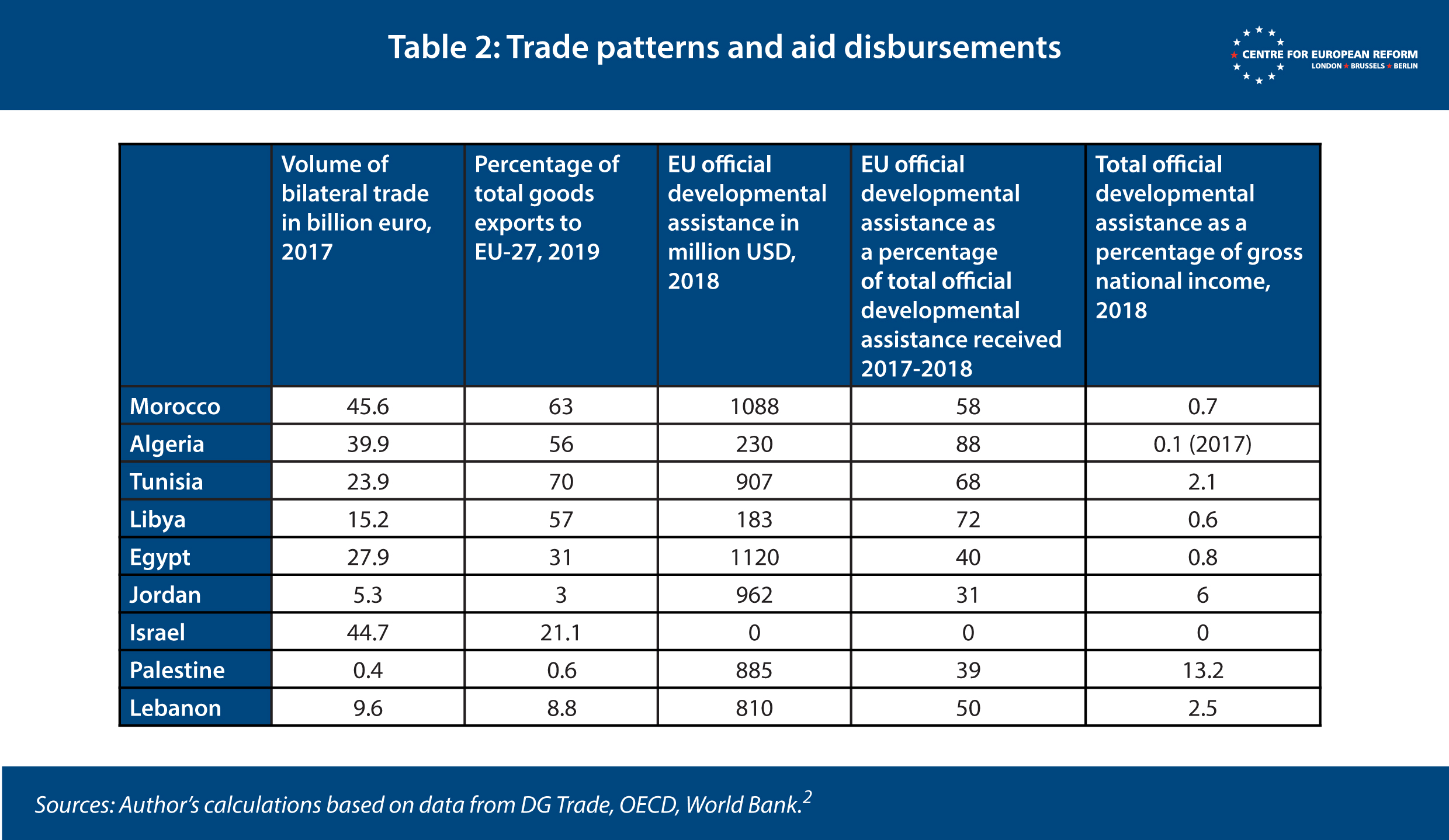

The EU’s approach towards its neighbours in the Middle East and North Africa has failed to foster security, stability and prosperity since the 2011 Arab Spring. The Syrian conflict, ongoing since 2011, has devastated the country and severely weakened neighbouring Lebanon and Jordan. Libya, persistently unstable since the Western-backed overthrow of long-time ruler Gaddafi in 2011, has been mired in civil war since 2014. Meanwhile, in Egypt and Algeria, poverty, corruption and authoritarianism are fuelling social unrest under a thin veneer of stability. Tunisia and, to a lesser extent, Morocco, are the only bright spots in the region. Tunisia has been a democracy since 2011, and has sought to build closer relations with the EU. However, its economic growth has been weak and its democracy remains fragile. Throughout the region, extremists thrive on poverty, high unemployment and political polarisation, which also fuel migration towards Europe (Table 1).

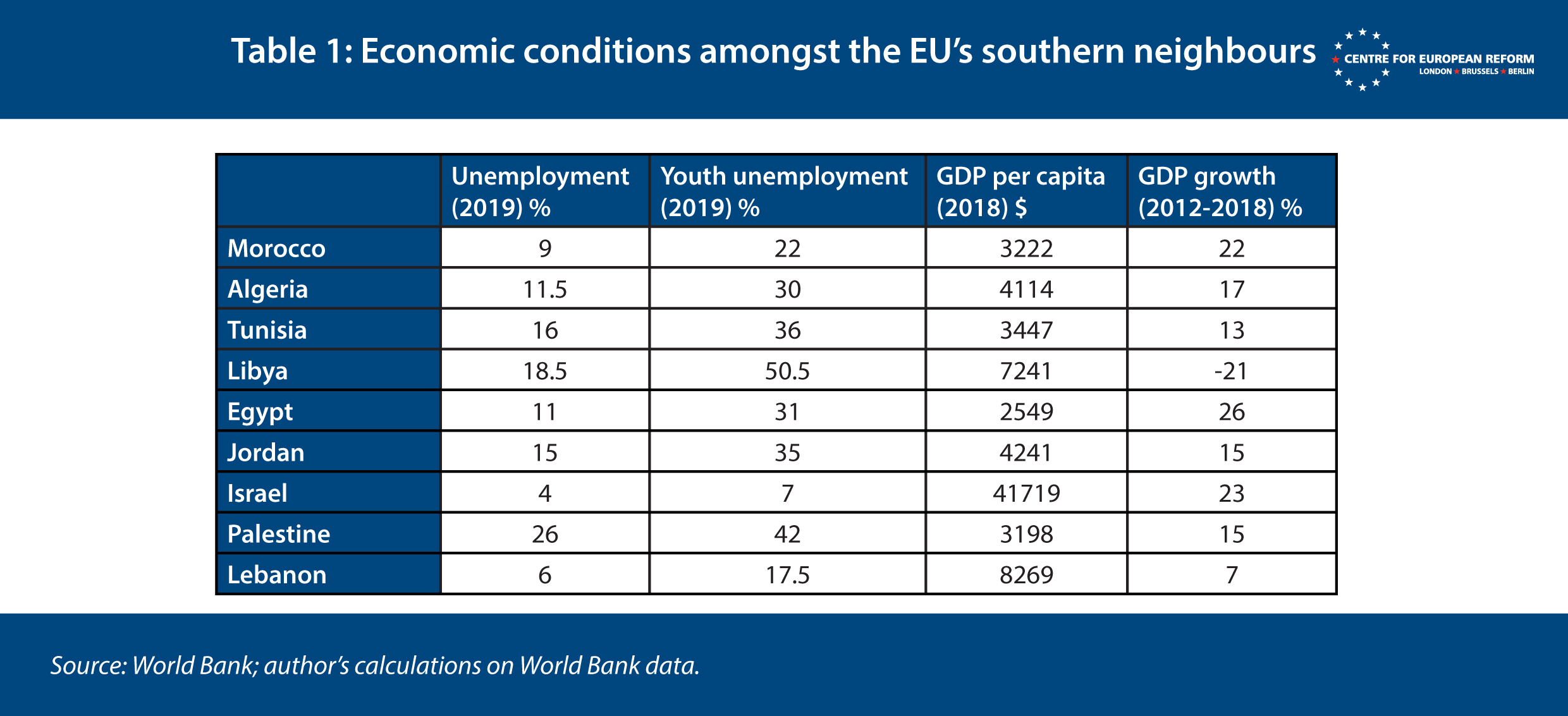

Countries in the MENA region vary widely in terms of the depth of their economic links to the EU.

This section provides an overview of the EU’s southern neighbours, and the Union’s relationship with each. The EU’s relationships with most of its neighbours are based on ‘Association Agreements’, which include trade agreements. These agreements are focused on tariff reductions for industrial goods. Though most of the countries have large agricultural sectors, the agreements do not liberalise trade in agricultural goods, although the EU has implemented ad-hoc reductions of tariffs and quotas on these. The EU is also in the process of negotiating Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) with Morocco and Tunisia. These are much broader trade agreements that involve regulatory and legal approximation to the EU’s acquis, the elimination of non-tariff barriers and the adoption of EU product standards – meaning that producers in many sectors will be able to export more easily to the EU and to the many countries that accept EU standards. Trade liberalisation is asymmetric, with partner countries maintaining protective measures over a transition period, while the EU removes them up front. Moreover, by adopting EU rules, countries should also be able to attract more foreign investment.

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region vary widely in terms of the depth of their economic links to the EU, as can be seen from Table 2. The countries in the Maghreb have deep links to the EU – particularly Morocco and Tunisia, which depend on the European market for around two thirds of their goods exports and are large recipients of EU development assistance. In contrast, countries in the Middle East have looser economic ties with Europe. Even Israel and Egypt, which have substantial trading relationships with the EU, are not greatly dependent on trade with Europe, as they also trade extensively with other countries. Finally, Jordan, Palestine and, to a lesser extent, Lebanon receive substantial EU assistance but have a very low volume of trade with the EU.

Morocco

Like Tunisia, Morocco has long aligned itself with the EU in foreign policy. It is one of the EU’s closest partners in the MENA, and a rare example of stability in the region. Europeans view Morocco as an important partner, not only economically but also for controlling migration flows and countering terrorism. Morocco applied to join the European Community in 1987. The EU rejected the application based on the fact that Morocco is not a ‘European state’, as what is now Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union stipulates that EU members must be. The Moroccan monarchy came through the Arab Spring unscathed, adopting a new constitution that preserves the king’s power.

A strengthening of EU-Morocco relations is possible, but will require significant political commitment on both sides.

Morocco has an Association Agreement with the EU, which entered into force in 2000, and was complemented by an additional agreement on agriculture and fisheries in 2010. The EU is Morocco’s biggest trade partner and one of the largest recipients of EU financial support in North Africa, with €1.3-€1.6 billion allocated in total between 2014 and 2020 through the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) alone. In 2013 the EU and Morocco began negotiating a DCFTA, but talks were quickly suspended, with Moroccans sceptical about its economic benefits. The situation was further complicated in 2016, when the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that the EU’s existing agreements with Morocco could not be applied to the Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara.

The two sides have now resumed negotiations over a DCFTA after the EU revised its existing agreements with Morocco, with the European Parliament voting in January 2019 to extend them to cover the Western Sahara, while not recognising Morocco’s claims to the area. There is a good chance that negotiations will make progress, as Morocco is keener than it was on deepening trade ties with the EU. In contrast, plans to deepen migration co-operation by striking readmission and visa facilitation agreements are unlikely to make progress: Morocco is reluctant to take back third country nationals, as the EU wants it to do; and member-states are unwilling to liberalise visas for Moroccans. A strengthening of EU-Morocco relations is possible, but will require significant political commitment on both sides. Moreover, the Western Sahara question could continue to be an obstacle to deeper relations, as the issue of whether EU agreements can apply to the region has not been fully resolved.

Algeria

The Algerian regime was able to avoid the turbulence of the Arab Spring, with President Abdelaziz Bouteflika retaining power. However, his decision to seek a fifth term as President prompted protests in early 2019 by the pro-democracy ‘Hirak’ movement, and ultimately he resigned. His resignation has not resulted in major changes in Algeria’s governance, as the army remains in overall control and has little intention of undertaking significant democratic reforms. Algeria’s economy remains overly dependent on hydrocarbon exports, and the country is vulnerable and has been hit by the recent collapse in oil prices. The country’s economic woes could spark further demands for reform and anti-government unrest.

The EU has supported the consolidation of Tunisia’s democracy, and attempted to deepen ties.

The EU has had an Association Agreement with Algeria since 2005, but the relationship is not particularly close. Like its neighbours Morocco and Tunisia, Algeria’s co-operation in countering terrorism and reducing migration is important to the EU. However, unlike its neighbours, Algeria has a balanced trading relationship with the EU: the country is the third largest gas supplier to the EU at a time when the Union is seeking to diversify its sources of energy and reduce its dependence on Russia. According to Eurostat, the EU currently imports 11 per cent of its gas and 3.5 per cent of its oil from Algeria. Moreover, Algeria does not receive much financial support from the EU: its ENI allocation for the 2014-20 period only amounts to around €250 million in total.

The Algerian government has little appetite to build a much closer relationship with the EU. Algerians have criticised the EU-Algeria Association Agreement for benefitting the EU more than Algeria, and the country’s leadership does not want a DCFTA, which would require it to liberalise the economy significantly. Politically, the government has little desire to deepen ties with Europe. Algeria has sought to diversify its foreign relations to enhance its independence. It has a close relationship with Russia, and is a major buyer of Russian military equipment – the third largest between 2014-18, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.3 Algeria has also signed a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ with China, an important upgrade in bilateral ties with Beijing.

Tunisia

Tunisia is one of the EU’s closest partners in the MENA region: it has sought strategic alignment with Europe, and is a large recipient of EU funding. Tunisia is the only success story of the Arab Spring. After the overthrow of Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime in 2011, the country became a democracy, and is rated as ‘Free’ by Freedom House, ranking higher than Hungary and all the countries in the Western Balkans and the EU’s Eastern Partnership.4 However, while Tunisia’s democracy has gradually consolidated, it remains fragile. The economy is weak, with growth of only 13 per cent between 2012 and 2018, high inflation, unemployment at around 16 per cent and youth unemployment at 36 per cent. Tunisia also faces external security challenges from the ongoing conflict in neighbouring Libya, instability in the broader Sahel region to its south, and domestic extremism and terrorism.

The EU has supported the consolidation of Tunisia’s democracy, and attempted to deepen ties. In November 2012, relations were symbolically upgraded to a ‘Privileged Partnership’, and negotiations for a DCFTA were launched in late 2015. However, these talks have made little progress due to limited political enthusiasm and opposition from Tunisian civil society and trade unions, who think that its economy will struggle to adapt to EU regulations and that the EU is pushing a neoliberal agenda that risks harming Tunisia. There is also limited backing in business circles, not least because the EU is unwilling to significantly liberalise agricultural trade, an important export sector for Tunisia. The EU and Tunisia are also trying to deepen migration co-operation, and are negotiating a visa facilitation agreement and a readmission agreement in parallel. But negotiations have not been smooth, as the EU is unwilling to make it easier for Tunisians to obtain visas until Tunisia agrees to the readmission agreement. Tunisia is unwilling to do this, as the EU insists that it must commit to taking back third country nationals as well as its own citizens. Renewed political momentum on both sides will be necessary if the EU and Tunisia want to deepen their relationship.

Libya

Libya has never had close relations with the EU. After Gaddafi was overthrown in a British and French-led intervention in 2011, Europe did not do enough to help Libya rebuild. Once the country’s fragile post-Gaddafi government imploded in summer 2014, the EU helped broker a new unity government, the Government of National Accord (GNA). The EU was mainly concerned with controlling migration and countering terrorism: it provided the GNA’s coastguard with training and support to reduce migration, and some member-states helped Libyan militias defeat the Libyan branch of IS. However, Europe did little to consolidate the GNA’s authority over Libya. Member-states were divided and unable to prevent the conflict between the GNA and its main opponent, Khalifa Haftar, from escalating, while the UAE, Russia and Turkey became increasingly involved.5 France, together with Russia, Egypt and the UAE provided support to Haftar, while Italy supported the GNA along with Turkey and Qatar. A direct confrontation between Turkey and Egypt, or Turkey and Russia is now possible. In the medium term, Libya risks being de facto partitioned into a western part that is aligned with Turkey, and an eastern one that is subject to Russian influence, potentially leaving Europe exposed to attempts to manipulate migration flows.

Egypt

Egypt is the most populous state in the EU’s southern neighbourhood, with over 100 million inhabitants. Following the 2013 military coup that overthrew democratically elected President Mohamed Morsi, Egypt has been ruled by a former general, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who has cracked down on dissent and abused human rights. The government has presided over some economic growth, but Egypt remains highly unstable, as highlighted by large-scale protests against the regime in late 2019 and an extremist insurgency in the Sinai peninsula.

Europe has prioritised stability and extensively supported Egypt despite the authoritarianism of its government.

The EU’s approach towards Egypt is essentially the same as it was in the pre-2011 Mubarak era: Europe has prioritised stability and extensively supported Egypt despite the authoritarianism of its government. Together with Morocco and Tunisia, Egypt has been one of the main recipients of EU funding in the region: according to the OECD, between 2014 and 2018 Egypt received over €1.5 billion in EU development assistance. Member-states value Egypt’s co-operation to reduce migration and fight terrorism, appreciate the stabilising role it plays in the Gaza strip, and hope to benefit from its newly discovered gas resources. Moreover, Egypt is an important economic partner for some member-states: for example between 2014 and 2018 the country was the largest destination of French defence exports.6

Egypt has had an Association Agreement with the EU since 2001, and trade in agriculture and fish was further liberalised with an additional agreement in 2010. A DCFTA has been on the agenda since 2013, but formal negotiations have not started as the Egyptian government has limited appetite to build closer commercial relations with the EU. Although the EU accounts for around 60 per cent of foreign direct investment into Egypt, the country only exports 31 per cent of its goods to the EU.7 This makes it less dependent on access to the EU market compared with other North African countries like Tunisia and Morocco. Moreover, Egypt has also increasingly sought to diversify its foreign relations to enhance its independence. Between 2013 and 2016, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have provided Egypt with around $30 billion in aid, allowing Sisi’s government to consolidate its position.8 Overall aid from the Gulf States to Egypt between 2011 and 2019 is difficult to calculate, but may be as high as $92 billion, dwarfing EU assistance.9 Egypt has also developed closer relations with Russia, opting to buy the Russian Su-35 jet instead of the US-made F-35.

Jordan

Jordan is probably the EU’s closest partner in the Middle East. An Association Agreement between the EU and Jordan has been in force since 2002 and forms the institutional foundation of their bilateral relationship. An additional agricultural agreement was signed in 2007, and the EU and Jordan also have an aviation agreement and a mobility partnership that serves as the foundation for co-operation on migration. The Jordanian monarchy was able to ride out the Arab Spring while only implementing relatively modest reforms to governance, and Jordan remains one of the most stable countries in the Middle East. However, it has faced a range of economic and security challenges as a result of the civil war in neighbouring Syria, and the rise of extremism. Jordan is hosting over a million Syrian refugees in addition to its Palestinian refugee population, which has strained its economy and services.

The EU has provided Jordan with extensive financial support to help it deal with the social and economic challenges it faces. The country is a large recipient of EU funds, with an overall ENI allocation of €567-€693 million between 2014 and 2020. Moreover, since the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011, the EU has provided Jordan with around €1.3 billion of support for its large refugee population, and made other concessions such as temporarily loosening rules of origin requirements for certain products, making it easier for them to enter the EU tariff-free. The EU and Jordan are currently negotiating visa facilitation and readmission agreements, and an Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance of Industrial Products (ACAA). The agreement, which would cover electrical goods, toys and gas appliances, would allow Jordan’s authorities to assess whether products meet EU standards, reducing compliance costs for businesses. Member-states have also authorised the EU to negotiate a DCFTA with Jordan, but negotiations have not yet started due to lack of interest on the latter’s part.

Israel

The EU has extensive commercial and political ties with Israel, the wealthiest and most developed state in the Middle East. The 2000 Association Agreement forms the institutional basis of the EU-Israel relationship. In 2013, the two also struck an ACAA on pharmaceutical goods, which can potentially be extended to other fields.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s new coalition government has promised to annex parts of the West Bank.

The EU’s relations with Israel are tense because of Israel’s moves to undermine the two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict that the EU is committed to. But the EU has done little to prevent the erosion of the two-state solution.10 It has deepened its relations with Israel, while failing to deter Israel from building settlements in the occupied territories. The EU maintains a policy of ‘differentiation’, according to which its agreements with Israel do not apply to the territories it occupies, but in practice the EU’s enforcement of differentiation is lax. For example, while member-states should clearly require products imported from illegal settlements to be labelled as such, few are doing so. The EU’s unwillingness to take a tougher stance towards Israel’s actions stems in part from its own divisions, with Hungary in particular vetoing EU statements criticising Israel.

Emboldened by President Donald Trump’s pro-Israel stance, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s new coalition government has promised to annex parts of the West Bank. If Netanyahu goes ahead with the plan, this would probably make a viable Palestinian state impossible, spelling the end of the two-state solution and marking a new phase in EU-Israel relations. But even if Netanyahu steps back from the brink, EU-Israel ties are unlikely to improve.

Palestine

The EU does not recognise Palestine as a state, although some of its member-states do. EU-Palestine relations are underpinned by an Interim Association Agreement on trade and co-operation, concluded in 1997, and complemented by a 2012 additional agreement on agriculture and fisheries trade. At around €400 million in 2017, trade between the EU and the Palestinian territories remains very small. However, as part of its long-standing commitment to advance the two-state solution, the EU has been the biggest donor of aid to the Palestinian Authority (PA), with its allocated support through the ENI alone worth a planned €1.8-€2.2 billion between 2014 and 2020. The EU has also provided training for the PA’s security forces though a police training mission active since 2006. The EU has become deeply invested in the PA’s survival, and has failed to press it to uphold democratic standards and the rule of law. In contrast, the EU has a no-contact policy towards Hamas, the extremist group that controls Gaza.

Palestinian economic development remains severely constrained by Israel’s restrictions on movement and access in the West Bank, and its blockade of Gaza, where humanitarian conditions are dire, with a lack of clean water and an unstable electricity supply. According to the World Bank, the Palestinian economy is expected to shrink between 7.6 per cent and 11 per cent this year.11 Meanwhile, the enduring political cleavage between the Fatah-dominated PA in the West Bank and Hamas-controlled Gaza remains an obstacle to a united Palestinian leadership, to easing tensions with Israel and to improving humanitarian conditions in Gaza. The situation is likely to worsen if the Israeli government goes ahead with its planned annexation of parts of the West Bank. In this scenario, violence might erupt and the PA might collapse. This would have a destabilising effect in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, forcing Israel to assume the burden of directly administering these areas, destabilising Jordan, and hurting Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbours.

Lebanon

Lebanon has been heavily affected by the spillover from the conflict in neighbouring Syria, and weakened by political strife. The country hosts around 1 million registered Syrian refugees and is going through a period of political and economic turmoil. Large-scale anti-government protests began in late 2019, fuelled by the economic situation, government corruption and mismanagement, and sectarianism. As the coronavirus pandemic reached Lebanon, the country stood on the verge of bankruptcy: in March Lebanon partly defaulted on its debt, which stands at 170 per cent of GDP, and in May it requested an International Monetary Fund bailout.

The basis of EU-Lebanon relations is an Association Agreement struck in 2002. The EU’s trade with Lebanon is limited, and its political engagement has been complicated by Hezbollah’s role in the country’s governance. In 2013, the EU declared the group’s military wing a terrorist organisation, while continuing to engage with its political wing. Nevertheless, the EU has provided substantial support to Lebanon in helping it deal with the consequences of the Syrian conflict, particularly in helping it care for its very large refugee population. Lebanon has received a total of around €1.8 billion in EU assistance since 2011.12 The EU has also supported Lebanon’s security sector, providing funding for capacity building, border management and countering terrorism. And several EU member-states contribute troops to the UN peacekeeping mission in southern Lebanon.

The EU and its member-states have been the largest donors of humanitarian aid to Syria.

Syria

Like Libya, Syria has never had close relations with the EU. The EU has largely been a bystander in Syria’s conflict, despite the fact that the flow of refugees from the country was the key reason for the migration crisis of 2015-16. In May 2011, after Bashar al-Assad’s regime brutally repressed protests, the EU suspended bilateral co-operation with the Syrian government and imposed sanctions, including a ban on oil imports from Syria. The EU and its member-states have been the largest donors of humanitarian aid to Syria, providing a total of around €17 billion since the start of the conflict according to the European Commission. Some member-states played an important role in the international military coalition that defeated IS in Syria. But, despite some Franco-German efforts, Europe has had almost no influence on the political process to resolve the conflict, with Russia and Turkey taking the lead thanks to their extensive military presence in Syria itself. The EU now faces a dilemma of whether to help Syria rebuild unconditionally, potentially helping to keep Assad in power, or whether to sharpen sanctions and tie reconstruction assistance to a political transition, potentially prolonging human suffering.

The limits of the EU’s approach towards the southern neighbourhood

The EU has had little success in its efforts to promote stability, security and prosperity amongst its southern neighbours. In large part, this is because the Union has been primarily concerned with reacting to immediate crises rather than thinking long-term. Its approach has been dominated by providing humanitarian assistance and by concerns about migration and terrorism. But this approach does not serve the EU’s long-term interests, as it does little to foster genuine stability amongst its neighbours. The EU has only provided modest support to countries where its efforts to promote reform stood a good chance of being successful. In particular, with more EU help Tunisia could become a prosperous and stable democracy and EU ally in North Africa, adding to the Union’s security and to its soft power. At the same time, the EU has continued to provide substantial unconditional support to authoritarian regimes such as Egypt, since member-states are keen to maintain good relations and economic links, and are concerned that the alternative would be instability and higher migration. But unconditional EU support disincentivises economic and political reform, and ultimately may well undermine the EU’s aim of fostering stability.

The EU’s political and economic offer to its southern neighbours is too limited to encourage them to undertake major economic and political reforms, or to build much deeper ties to the EU. The amount of financial assistance provided by the Union is small compared with the scale of the challenges faced by its partners, and the amount of assistance provided by other donors such as the Gulf states. The sums involved are comparatively small even in the cases of Morocco and Tunisia, two of the largest recipients of EU assistance and the EU’s closest partners in the MENA region. Moreover, the EU’s support has not always been effective, acknowledged by partners, or visible. For example, a report by the European Court of Auditors on EU support to Morocco concluded that European funds were not well-targeted, went largely unnoticed by the Moroccan population, and were poorly co-ordinated with national aid, with member-states keen to maintain their own visibility.13

In terms of trade, the EU’s current association agreements with its southern neighbours offer only limited market opening. The agreements provide tariff-free trade in industrial goods but only partly liberalise agricultural trade and fisheries. The EU is negotiating DCFTAs with several countries in the region, which offer a much deeper level of market integration. However, in all cases these negotiations have made limited progress, as DCFTAs require signing up to much of the EU’s acquis. This entails profound economic and institutional reforms that are difficult to implement, economically costly, and politically difficult, as they are likely to go against the interests of influential domestic groups. Moreover, there has often been opposition to negotiating DCFTAs from civil society. For example, in Tunisia influential groups are sceptical of market liberalisation. In terms of mobility for their citizens, the EU’s offer to its neighbours is also limited, with member-states unwilling to expand legal migration routes. At the same time, negotiations on readmission agreements have been blocked by the EU’s demand that countries must take back nationals from countries other than their own.

The EU’s political offer to partners is also too small. The EU does not offer countries to its south a deep partnership, but only a relatively modest upgrade of trading relations. In the EU’s eastern neighbourhood, Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia have been willing to conclude and implement DCFTAs because they viewed them as a stepping stone towards their ambition of EU membership. Even though membership is at best a very distant prospect for them, the Union has never ruled it out, as all three countries are geographically European and thus in theory eligible to be members. In contrast, the countries to the EU’s south are not geographically in Europe, and therefore cannot become EU members. The offer of upgraded trade ties is not appealing enough to convince governments in these countries to undertake politically costly reforms.

The EU does not offer countries to its south a real partnership, but only a relatively modest upgrade of trading relations.

Europe’s limited security footprint in the region makes it a less attractive partner. Member-states’ contribution to UN peacekeeping in Lebanon has been valuable, and some member-states contributions to UN peacekeeping in Lebanon have been. However, the EU and its member-states have been powerless to affect the course of the civil war in Syria, or to halt Israel’s gradual undermining of the two-state solution. In Libya, the EU failed to consolidate the country’s fragile post-Gaddafi government, and the country descended into a destructive civil war. The EU’s security efforts have also at times been undermined by a striking lack of co-ordination between member-states. In Libya, France, Greece and Cyprus are primarily concerned with reducing Turkey’s influence and have supported Haftar together with Russia, Egypt, the UAE and others. Meanwhile Italy has been supportive of the UN-backed GNA, and many member-states are just as concerned about Russia’s growing presence in Libya as they are about Turkey’s footprint.

Then there is the lack of an external threat encouraging countries in the EU's south to move towards Europe. For many of Europe’s eastern neighbours, moving closer to the EU is a response to the threat they perceive from Russia. In contrast, the countries to Europe’s south see many alternatives to forging closer links to the EU. The Gulf states are influential regional powers, and offer an alternative political and economic model to the European one. Turkey is also an increasingly important player, and has become highly influential in Syria and now also in Libya thanks to its support for the GNA.

Russia is also a significant actor, although more in political than economic terms. Moscow is willing to use force in the region, while also trying to present itself as a mediator, for example in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or in Syria. Russia has propped up Assad, set up permanent military bases in Syria, and cemented its influence in Libya through its support for Haftar. Moscow is also a major arms supplier in the region, in particular to Algeria and Egypt.

Finally, many countries in the region are also building closer trading and political links with China and are particularly attracted by Beijing’s policy of not interfering in their domestic affairs. Beijing has concluded a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ with Egypt and Algeria, and has close political relationships with Israel, Jordan and Morocco. As part of its Belt and Road Initiative, China has plans to invest in infrastructure projects across the region. Its main focus is Egypt: Beijing has invested in the Suez Canal Economic Zone and is helping finance the construction of a new Egyptian administrative capital. Israel is also important for Beijing, and a Chinese company has concluded a deal to build and operate a new seaport near Haifa, despite opposition from the US.14

The challenge for the EU

The EU’s failure to generate prosperity and security and to promote real stability amongst its southern neighbours will continue to undermine European security. High population growth, combined with the effects of climate change and with weak or unequal economic growth, will continue to fuel migration towards Europe, social discontent, extremism and instability. At the same time, the EU’s influence in the region is likely to wane as China, Russia and Turkey become increasingly assertive and influential. The trend will be exacerbated if the US continues to be a destabilising force, which will be the case if Trump is re-elected as president later this year. But even if Democratic candidate Joe Biden becomes president, the US is unlikely to be as involved in the MENA as it was, and will want Europeans to do more for their own security. In time, Europe’s comparative loss of influence will make it harder for it to control migration, as its neighbours will be less dependent on Europe, and therefore able to extract a higher price for co-operation.

The need for the EU to change its approach towards the region was already clear before the coronavirus pandemic. With COVID-19 the EU needs to rethink its relationships with its southern neighbours more urgently and take a more strategic approach. The pandemic will weaken several of the EU’s southern neighbours. At the time of writing, many of them have not recorded very large outbreaks. However, most are not testing widely, so the real number of infections may be substantially higher. If the number rises, most countries in the region will be in a difficult position as their health systems are patchy and underfunded.

Even if they are spared from the worst of the pandemic itself, countries in the region will not be able to escape its economic consequences. Aside from the direct economic impact of restrictions to counter the spread of the virus, countries will also suffer from the global slowdown: they are likely to lose export revenues and to see a drop in remittances and foreign investment. Their currencies will depreciate and lead to a rise in inflation, and their foreign-currency denominated debt will balloon. They will also lose income from tourism, which represents a large share of GDP across the region and is likely to be significantly curtailed by the pandemic for at least the next year (Table 3).

Economic difficulties are likely to strain social cohesion, and fuel further instability, political polarisation, extremism and conflict. Many governments will have to cut their budgets, reducing social spending. They will also lack the economic resources to enact fiscal stimuli to restart their economies. Ongoing conflict and rising unemployment are likely to lead to a rise in migration to Europe.

The EU should not think it can insulate itself from instability amongst its neighbours. Growing social strife may lead to the rise of extremism and potentially state failure. Ultimately this could even lead to the rise of hostile actors on Europe’s doorstep, perhaps in the form of terrorist states like the now defeated IS in Syria. And if more people try to reach Europe in search of better lives, this will fuel populist forces in Europe and lead to increasing acrimony between member-states.

What the EU should do

In the immediate term, the EU’s priority should be helping its neighbours in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic and its economic consequences. The EU and its member-states should assist Europe’s southern neighbours by providing them with medicines and equipment, and sharing public health advice to make sure that the number of infections is suppressed and remains low. The EU should also help its neighbours economically, to prevent them from becoming destabilised, while ensuring that its assistance is visible and publicly acknowledged. Aside from fighting the pandemic, the EU should also i) spend more money on economic assistance ii) take more responsibility for the region’s security iii) provide greater incentives for reform; iv) make its support more conditional; and v) develop an ‘associate membership’ model that democratic countries in the region can aspire to.

Enough money

The European Commission appears to be taking the challenge seriously. The Commission has proposed a large increase in EU resources devoted to external policy in the 2020-27 EU budget, for a total of €118.2 billion in 2018 prices. The main instrument will be a new Neighbourhood, Development and International Co-operation Instrument (NDICI), worth €86 billion in 2018 prices. The instrument would merge most of the EU’s existing external instruments such as the €30 billion European Development Fund (currently outside the EU budget), the Neighbourhood Instrument, the Development Co-operation Instrument and the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights. A minimum of €22 billion would be reserved for countries in the EU’s neighbourhood, a substantial increase over the current €15 billion.15

If the EU wants its southern neighbourhood to be more stable, it needs to be more visible politically.

The Commission argues that, because it blends a range of existing instruments into one, its new NDICI will be more flexible and responsive than current tools, for example making it easier to reallocate funds from one year to another. In addition, the Commission proposed measures to promote more investment. A ‘European Fund for Sustainable Development+’, embedded in the NDICI, and an External Action Guarantee are meant to allow the EU to promote private and public investments by partly covering investment risks.

The Commission’s proposals are ambitious, and signal that it is taking the challenge in its neighbourhood seriously. However, negotiations between member-states could mean this figure will be substantially reduced. Spending on external priorities may be one of the first victims as member-states negotiate to reduce the overall size of the budget. This would be short-sighted, as the EU will pay the costs of inaction over time. If it wants to avoid more problems in the future, it needs to invest now.

A larger European security role in the region

If the EU wants its southern neighbourhood to be more stable, it needs to be more visible politically, and take more responsibility for the region’s security. There is only so much the EU can do in Syria, where it has been relegated to the sidelines as Russia, Turkey and Iran decide the country’s future. But the EU can still take a more active role in pushing for a ceasefire in Libya, and trying to maintain that country’s unity. If member-states converged on a common stance, they could push Egypt, Turkey, Russia and the UAE to moderate their goals in Libya, securing a stable ceasefire. Europeans should then be willing to police the ceasefire to prevent further fighting and stabilise the situation while working towards a broader settlement. Meanwhile, if the Israeli government carries out its annexation plans the EU must respond robustly, by suspending their bilateral association agreement and toughening existing differentiation measures that treat the occupied territories as separate from Israel. Otherwise the EU will lose credibility.

More broadly, the EU should be ready to provide training for the police and security forces of partners across the region, ensuring that they operate in a manner that is effective, proportionate and accountable. The EU and its member-states can help partners in building more effective programmes to counter extremism and promote deradicalisation and reintegration of former fighters. In this sense, proposals by the High Representative and the Commission for a ‘European Peace Facility’ go in the right direction. The Facility would be a financial instrument outside the EU budget, worth around €8 billion over seven years. It would pay for the common costs of EU military and civilian operations as well as the training, equipment and operations of partner countries, neither of which can currently be done through the EU budget.16 Member-states should not torpedo the plan.

If Europeans want to be more influential in the region, member-states will need to be fully aligned with EU policy and willing to work together rather than ineffectively pursue their own narrow interests. Member-states can do more to provide the EU’s initiatives with added political heft. For example, they could involve EU institutions in their bilateral relations with partners, inviting the High Representative/Vice President, the Commission President, or the European Council President to summits. Member-states could also involve heads of EU Delegations in planning bilateral meetings with the host country. Individual member-states could also take the lead on political and security relationships with specific countries if they have particularly deep ties to them, following the EU+ E3 framework. The model, which includes France, Germany the UK and the High Representative, proved very successful in negotiating the nuclear deal with Iran.

A more attractive offer to partners

If the EU makes its partners a more attractive offer, it can encourage them to undertake economic and governance reforms that boost their stability and prosperity. Because DCFTAs are a powerful trigger for domestic reforms, the EU should make them much more appealing. The EU should be willing to open DCFTA talks with all countries in the region with which it has good relations. The EU’s offer should be tailored to appeal to each partner. For example, regulatory approximation of the EU’s acquis could be limited to those sectors that are particularly appealing to partner countries. In general, DCFTAs should have longer adaptation periods with more exceptions from liberalisation for the partner country. They should also offer partners greater market access for agricultural produce than they currently envisage, reducing tariffs and increasing quotas. The EU should also provide generous support for local businesses during adaptation periods to minimise negative economic impacts that may fuel social strife and instability.

In parallel, the EU should make clear it is willing to grant partner countries visa free travel for their citizens if they fulfil the necessary criteria on border management and readmission, internal security and fundamental rights. To overcome existing resistance to a DCFTA amongst civil society and businesses in partner countries, the EU should engage directly with civil society groups, to show it listens to the concerns of citizens. The EU should also encourage governments to include representatives from these groups in formal consultations, and try to negotiate as transparently as possible to ease their fears. Furthermore, the EU should provide technical assistance to prepare countries for adopting the DCFTA, helping to build capacity in their civil service.

The EU should develop an ambitious offer for an ‘associate membership’ of the Union.

Even with these added inducements, negotiating a DCFTA may still prove too ambitious even for the two most interested states, Morocco and Tunisia. Because of this, the EU should also offer its partners a more modest upgrade of their existing FTAs as a possible stepping-stone to a DCFTA. The upgrade would be centred on liberalising agricultural trade by removing most tariffs and increasing quotas, something that countries in the region want. This would contribute to social and economic stabilisation across the region. It would also build trust, allowing governments to inject new momentum into DCFTA negotiations, with greater support from citizens and businesses. As part of an FTA upgrade, the EU should offer greater opportunities to citizens from these countries, offering to expand legal migration pathways, with member-states increasing the number of work visas they grant. The EU should also make greater use of sectoral integration. For example, the Union could make greater use of ACAAs, like the one on pharmaceuticals that it has with Israel.

Support to be more conditional and targeted

Better trade ties should be available to most of the EU's southern neighbours, but EU financial support should be made more conditional on their respect for human rights and alignment with EU foreign policy priorities. The EU should provide more assistance to countries that are democratic and aligned with its foreign policy, and less to countries that do not respect human rights or undermine EU foreign policy. It would not be credible for the EU to threaten to cut off all ties or assistance, as the Union often has an interest in co-operating with countries for a range of reasons, from migration and counterterrorism to helping them transition towards renewable energy sources. But the EU should seek to use the assistance that it provides to push them harder to respect human rights, and support its foreign policy. If they refuse, the EU should limit its assistance to priorities that directly benefit it and ordinary citizens in partner countries, such as directly financing green energy development, education or poverty alleviation programmes. The EU should also continue to try to strengthen civil society, and strengthen cultural links, by increasing its funding for student programmes and research exchanges.

A more conditional approach will only work if EU member-states are fully behind it, and if the goals are realistic. For example, Europe could not push a country like Egypt to undertake democratic reforms, but it could leverage its existing financial support to push it to be somewhat less repressive. The EU could also push Egypt to stop fuelling the Libyan conflict by curbing its support for Haftar. The EU can also make use of sanctions against officials implicated in human rights abuses. The EU may now find itself in a stronger position to exert influence due to the economic weakness of many of its competitors in the region: the Gulf states will be hard hit by low oil prices and are unlikely to be able to step in to provide large amounts of funding to compete with the EU.

Develop a partnership model that countries can work towards

The EU should develop an ambitious offer for an ‘associate membership’ of the Union that neighbours that cannot be full members can aspire to in the medium-term. The offer of associate membership could spur neighbours to enact further political and economic reforms, making them more stable, well governed and prosperous. Associate membership should only be on offer for democratic countries that fulfil the Copenhagen criteria, and would therefore qualify for EU membership were it not for their geographic location. However, the very existence of an associate membership model could prove to be a force promoting democracy in countries across the region.

What would associate membership involve? Associate members would benefit from extensive political and security co-operation with the EU and its member-states. They would be closely tied to the EU’s justice and home affairs policies, and foreign policy. They would send diplomats to the Council’s committees and working groups, attend the Political and Security Committee, be able to join EU ministers’ discussions on foreign policy as observers, and second their staff to the EU institutions. They would also participate in Common Security and Defence Policy missions and benefit from the EU’s defence initiatives, such as Permanent Structured Co-operation and the European Defence Fund.17

Associate members would benefit from extensive political and security co-operation with the EU.

Associate members would already have a DCFTA with the EU, meaning they would already have adopted the EU’s acquis in many areas. Associate members would also participate in EU agencies and in the single market for goods. They could join a customs union with the EU, making trade even easier by fully removing tariffs and reduce costly customs procedures. And, if they wanted to, associate members could eventually participate in the single market for services, as EEA members do. Associate members of the EU would receive extensive EU funding on EU membership terms. Their citizens would be able to travel freely to the EU and take up employment.

Associate EU members would be subject to all of the relevant EU legislation. An independent arbitration panel would settle disputes, with the ECJ’s opinion prevailing where the dispute is on the interpretation of EU law. Associate EU members would not have voting rights on the policy areas of the single market in which they participate, as they would not be full members. However, they would be able to influence EU decision-making through regular consultations with the Commission, be formally consulted during the revision of policies, and could take part in informal Council meetings relevant to their participation in the single market, as European Economic Area states already do on an ad-hoc basis. The EU would retain the right to suspend the agreement, or individual areas of it, to guard against democratic backsliding.

Conclusion

The EU’s ambition to be more ‘geopolitical’ should start close to home. The EU’s approach towards countries to its south has had limited success in meeting its goals of fostering security, stability and prosperity. The Union’s southern neighbours remain unstable, poor and often authoritarian, with high levels of unemployment and corruption, all of which fuels migration towards Europe. The EU’s focus on co-operating with neighbours to counter terrorism and migration, and its de facto support for authoritarian governments, have failed to promote genuine stability and economic growth. Meanwhile, Europe’s weak security footprint has failed to halt widespread instability and conflict, and enabled the rise of terrorist groups. The Union has done too little to help neighbours that were primed for reform and wanted close relations, like Tunisia, while providing substantial unconditional assistance to authoritarian governments such as Egypt. Member-states pursued their own aims, while paying lip service to a common EU policy.

The coronavirus pandemic will greatly increase economic difficulties for the EU’s neighbours, fuelling social discontent, political polarisation, extremism and potentially conflict. The EU should not think it can insulate itself from instability in its neighbourhood. Instability could directly threaten Europe if it leads to a rise in extremism and the resurgence of a terrorist state like IS. Increasing numbers of people will try to reach Europe, searching for better lives for themselves and fleeing from poverty, climate change and conflict. This will potentially fuel the growth of populist anti-immigration and anti-EU forces in Europe, and further weaken the EU itself. If Europe does not help its neighbours in dealing with the health and economic consequences of the pandemic, and rethink its policy towards the neighbourhood, it will simply be creating greater challenges for the future.

2: Data on bilateral trade is from the European Commission, Directorate General Trade. Data on official development assistance is from the OECD and includes EU institutions and member-states. Data on official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income is from the World Bank.

3: Pieter Wezeman, Aude Fleurant, Alexandra Kuimova, Nan Tian and Siemon Wezeman, ‘Trends in international arms transfers 2018’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2019.

4: ‘Global Freedom Score’, Freedom House, 2020.

5: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘The EU and US must work together to end the siege of Tripoli’, CER insight, January 30th 2020.

6: Pieter Wezeman, Aude Fleurant, Alexandra Kuimova, Nan Tian and Siemon Wezeman, ‘Trends in international arms transfers 2018’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2019.

7: EU Directorate General for Trade, 2020.

8: David Butter, ‘Egypt and the Gulf: Allies and rivals’, Chatham House, April 2020.

9: Michele Dunne, ‘Egypt: Looking elsewhere to meet bottomless needs’, Carnegie, June 9th 2020.

10: Beth Oppenheim, ‘Can Europe overcome its paralysis on Israel and Palestine?’, CER policy brief, February 26th 2020.

11: World Bank, ‘Palestinian Economy Struggles as Coronavirus Inflicts Losses’, June 1st 2020.

12: EU Directorate General for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, 2020.

13: ‘EU support to Morocco - Limited results so far’, European Court of Auditors, December 11th 2019.

14: Lisa Watanabe, ‘The Middle East and China’s Belt and Road Initiative’, ETH Zurich Centre for Security Studies, December 2019; Yahia Zoubir, ‘Expanding Sino–Maghreb relations’, Chatham House, February 26th 2020.

15: ‘Factsheet: The Neighbourhood, Development and International Co-operation Instrument’, European Commission, June 2nd 2020. See also: ‘A new neighbourhood, development and international cooperation instrument’, European Parliament Research Service, February 2020.

16: ‘Questions & Answers: The European Peace Facility’, European External Action Service, June 2nd 2020.

17: This means associate EU members would have closer political and security co-operation with the EU than EEA members currently do. The EU could then offer the same level of co-operation to EEA members, or it could insist that the offer is only available to associate members, as, unlike EEA states, they would not have the option of acceding to the EU.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

View press release

Download full publication