Can Europe overcome its paralysis on Israel and Palestine?

- The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has proved one of most intractable foreign policy issues for the European Union. Europe has poured diplomatic effort and money into the idea of a two-state solution. Why then is a resolution so far off?

- The last EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, was unable to translate diplomatic declarations into concrete action. Her support for the two-state solution helped to keep it alive at the level of rhetoric, but on the ground, Israel and the US took steps to dismantle it.

- Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has escalated Israel’s policy of annexing the West Bank de facto, expanding Israeli settlements there while displacing Palestinians. Proponents of annexation of the West Bank have been emboldened by US President Donald Trump’s ‘peace plan’. The Netanyahu government has also continued to impose punitive restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza, on the basis of the security threat posed by the Islamist militant group Hamas, pushing the strip into a humanitarian crisis. Israel’s policy of de facto annexation in the West Bank and its blockade of Gaza violate international law.

- The Trump administration has retreated from the two-state solution, openly favouring Israel and turning its back on the Palestinians. The US ‘peace plan’ accedes to the wishes of Israel’s nationalist right, including the annexation of 30 per cent of the West Bank, and proposals for a fragmented Palestinian entity that would be far from a contiguous state.

- Mogherini faced an extremely difficult international context. Alongside Netanyahu's close relationship with Trump, the prime minister nurtured relationships with illiberal, nativist governments in Europe, sowing division in the EU and paralysing its decision-making on Israel-Palestine. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas clung to power and blocked reconciliation between the two main Palestinian political factions, weakening the Palestinian national movement. At the same time, increasing Iranian dominance in the Middle East brought Israel and its Arab neighbours closer together, relieving pressure on Israel to change its policy towards the Palestinians.

- EU policy under Mogherini was flawed. She failed to adequately address the power asymmetry between the two sides. While the peace process has foundered, the bilateral relationship between Israel and the EU has deepened without any conditions being imposed, reducing the EU’s leverage.

- Mogherini should have pushed harder on the EU’s policy of ‘differentiation’, which excludes the settlements from the benefits of the Israel-EU bilateral relationship, and is one of few instruments the High Representative can use without further assent from the member-states.

- The EU also continued to provide financial assistance to the Palestinians without attaching sufficient conditions, which meant that EU aid helped to support an increasingly undemocratic and dysfunctional Palestinian Authority.

- In spite of, or perhaps even because of, the destructive position taken by the US, there are constructive steps that the new High Representative, Josep Borrell, can take to advance the peace process. The EU has plenty of leverage it could bring to bear: economic heft, large aid budgets, strong defence capabilities, and an extensive and experienced diplomatic service.

- Borrell could make a difference by promoting a number of policies: pushing for EU and international recognition of Palestine as a state; finding new formats for European decision-making that circumvent the need for consensus, for instance contact groups of willing member-states; strengthening the EU’s policy of ‘differentiation’; resisting calls to deepen the EU’s relationship with Israel any further without progress on the peace process; improving Europe’s strategic communication and public diplomacy in Israel; reviewing EU assistance to the Palestinians; and ending the no-contact policy with Hamas.

The Middle East peace process is one of the most consuming foreign policy problems facing the European Union. Europe has invested vast amounts of diplomatic energy and money into the idea of a two-state solution, but to no avail. On the ground, Israel is strengthening its control over the occupied Palestinian territory, and there is no Palestinian state on the horizon. Violence erupts periodically, at a high human cost. Why then has Europe been so ineffective in promoting the resolution it so desires?

This paper evaluates the EU’s policy towards the Israel-Palestine conflict under the last EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini. It weighs the shortcomings and successes of EU policy under Mogherini, and makes nine recommendations to the new High Representative, Josep Borrell.

When Mogherini assumed her post in November 2014, she said that a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could be reached within her five-year term. She was wrong. As her term ended, she acknowledged that the best the EU could achieve was to ‘avoid’ the dismantling of the two-state solution.1 Indeed, much of her time in office was spent trying to stop the US and Israel from fatally undermining the two-state solution, and trying to keep member-states aligned with agreed EU positions. But while her support for the two-state solution helped to keep it alive at the level of rhetoric, Israel has created a reality on the ground that makes a two-state solution almost impossible. The EU has condemned Israel’s actions, but it has not imposed any practical penalties.

The EU has been constrained by a very unfavourable international environment. US President Donald Trump has thrown unconditional support behind Israel; Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has pursued a policy of divide and rule with the EU’s member-states; other conflicts and security threats in the EU’s neighbourhood have eclipsed the Israel-Palestine issue; and Arab states have begun to normalise relations with Israel, relieving the pressure on Israel to change its policy towards the Palestinians.

Though the political and security context in the Middle East is no less challenging now, Josep Borrell can and should go beyond diplomatic declarations. The EU has plenty of leverage: it is Israel’s largest trade partner and the biggest donor of aid to the Palestinian Authority; it also has the second highest level of defence spending globally. On the Israel-Palestine issue and beyond, Borrell will need to find ways to wield the EU’s plentiful resources more effectively, so that it can become a more powerful foreign policy actor.

Israel’s policy: Occupation and annexation

For decades, Israel has been annexing the West Bank de facto, encouraging Jews from Israel and the diaspora to move to settlements there. In 1995, the ‘Oslo II Accord’ agreement divided the West Bank into three areas: A, B and C. Built-up Palestinian areas were allocated as areas A and B, and were handed over to Palestinian Authority (PA) control (full control in Area A, but shared security control with Israel in Area B).2 The remaining 61 per cent became Area C, where Israel fully controls civil and security affairs. This division was intended to be temporary, but Israel did not withdraw as planned. Instead, it built settlements, entrenching Israel’s presence in the West Bank. The Israeli parliament has now begun a simultaneous de jure process, by passing laws that apply to the occupied West Bank.3

The settlement policy is one of the greatest obstacles to a two-state solution. Israel’s planning and construction policy in the West Bank is designed to fragment the remaining Palestinian-controlled territory, thus preventing the creation of a contiguous Palestinian state. One senior Israeli official said that so long as the Palestinians ‘refuse’ to come to the negotiating table, the Israeli government will continue to pursue the settlement project, rendering a future Palestinian state less contiguous.4 However, responsibility for blocking negotiations lies with both sides, and the stalled negotiation should not serve as a justification for violations of international law.

The settlement policy is one of the greatest obstacles to the two-state solution.

Israeli settlements in the West Bank are illegal under international law. The rules on occupation are set out in two instruments of international humanitarian law, the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention and the 1907 Hague Convention. According to the Geneva Convention, it is illegal for an occupying power to change the territory’s international status, government or demographics, by forced transfer of the local population or by transferring its own civilian population, for example.5 In the past, Israel has de jure annexed specific territories, which is illegal under international law. In 1967, Israel formally annexed East Jerusalem, and in 1981, it annexed the Syrian Golan Heights; moves that were deemed “null and void” by UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) 478 and 497 respectively.

Since 2013, the Israeli government has designated some settlements as ‘national priority areas’. Settlers have access to better services and infrastructure than the Palestinian residents of the West Bank (for instance roads, schools and hospitals) and their businesses receive preferential treatment. Settlers receive three times more in government subsidies than citizens inside Israel proper, in the form of discounts on mortgages and property prices, as well as disproportionate agricultural and infrastructure investment.6 Most settlements are located in Area C, where Israel has allocated 70 per cent of the land to settlements and just 1 per cent to the Palestinians.7 As the largest part of the West Bank, with the greatest concentration of natural resources, Area C could make a significant contribution to the Palestinian economy. Israel also operates two distinct systems of law in the West Bank: Jewish settlers come under Israeli civil law and are prosecuted in courts inside Israel proper; Palestinians come under military law and are prosecuted in Israeli military courts in the West Bank. In a leaked internal document from 2018, EU diplomats in Jerusalem and Ramallah outlined “systematic legal discrimination” against Palestinians in the West Bank.8

As a result of the policies of successive governments, the number of people living in the settlements has risen steadily (see Chart 1). The number of construction projects started in the settlements is nowhere near historic highs, but has been growing in recent years (Chart 2). There has been a particular increase in the establishment of settlement ‘outposts’ built on private Palestinian land without formal Israeli government authorisation. These outposts are illegal under Israeli law, although in reality they often have tacit support from the government (Chart 3).

In addition, Israel has pursued a policy of displacing Palestinians in the West Bank, denying them access to their land and resources. Palestinians wishing to build in Area C are required to request permits from the Israeli civil administration (the Israeli governing body in the West Bank) via an opaque process. The civil administration rejected 98.6 per cent of Palestinian applications to build in Area C from 2016-2018.9 This means that Palestinians, and also providers of humanitarian aid such as the EU and the member-states, end up building structures without permits, which then run the risk of being demolished by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Since 2014, the IDF has demolished or seized 474 EU or member-state-funded structures in the West Bank, valued at €1.45 million.10

Even more concerning is Israel’s shift from de facto to de jure annexation during the last Israeli parliament.

Even more concerning is Israel’s shift from de facto to de jure annexation during the last Knesset (Israeli parliament), from March 2015 to April 2019. Until now, the West Bank has been governed by a patchwork of law: the Palestinian Basic Law (the temporary constitution of the PA until a Palestinian state is established); the international law of occupation; local law from previous rulers like Jordan and the Ottoman Empire; and Israeli military law. Under international law, the occupying power should preserve the legal status quo as far as possible.11 But the Knesset is passing laws that apply to the occupied West Bank, slowly expanding Israel’s territorial jurisdiction. Sixty bills related to annexation were proposed during that Knesset, of which eight were approved.12

Following the release of the Trump administration’s plan for the Middle East peace process in January 2020, Netanyahu wanted to begin formal annexation immediately. But after a warning from Donald Trump’s senior advisor and son-in-law Jared Kushner he will wait until after Israel’s general election in March. The leader of the opposition Blue and White Party, Benny Gantz, has also endorsed proposals to annex parts of the West Bank. Yet annexing large parts of the West Bank would present a demographic problem for the Israeli government. If Israel brought hundreds of thousands of Palestinians under Israeli jurisdiction and granted them citizenship, it would undermine Israel’s status as a Jewish majority state. If the government did not grant full civil rights to Palestinians under its jurisdiction, it would create an indisputable one-state reality of unequal rights for two peoples, undermining Israel’s status as a democracy.

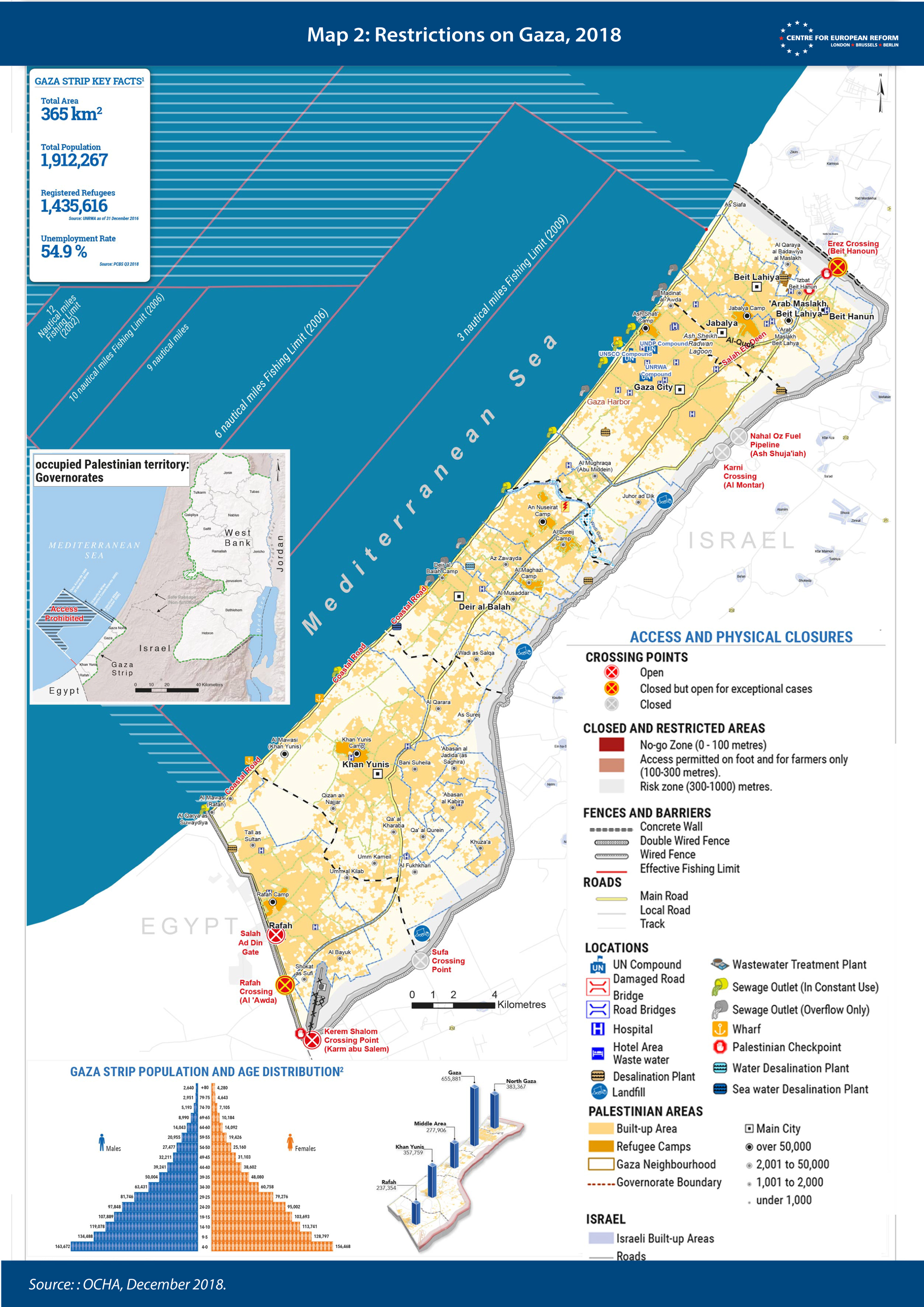

Israel continues to impose severe restrictions on the Gaza Strip, despite pulling its army and settlers out of the area in 2005.

Israel continues to impose severe restrictions on the Gaza Strip, despite pulling its army and settlers out of the area in 2005. In 2007, Hamas violently took control of the Gaza Strip from the PA. Since then, the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza has been tightly controlled by Israel and Egypt, and the PA (which still governs the West Bank) has imposed sanctions on the strip. Very few Palestinians are permitted to travel between the West Bank and Gaza, entrenching the social and political separation of the territories. Israel and Egypt cite security as the justification for the blockade.

Indeed, Hamas has carried out acts of terrorism against civilians and sabotaged past peace negotiations with violence. The organisation regularly fires rockets and improvised explosives into Israel; has used schools and hospitals in Gaza as military bases; and uses construction materials to build tunnels for terrorist activity and arms smuggling.13

But as a result of the blockade, Gazans are routinely denied access to electricity, clean water, medical care and building materials: 95 per cent of Gazan tap water is undrinkable, electricity is available for just four hours a day, and unemployment reached 47 per cent in the second quarter of 2019.14 Israel has a list of 118 ‘dual-use’ items – which can be used for military or civilian purposes – that are banned from entering Gaza, restricting the import of vital materials for manufacturing, information and communications technology and agriculture. The West Bank has a shorter list. The items on these lists are supplementary to those on the Wassenaar list – the international gold standard for controlled dual-use goods. The UN regards the Gaza Strip as part of the occupied Palestinian territory, despite Israel’s disengagement in 2005. There is a broad legal consensus that Israel has continued obligations to the people of Gaza because of the degree of control it exercises over the strip. Israel’s blockade violates its obligation to meet the basic needs of the population in Gaza, as set out in the Fourth Geneva Convention, and the First Protocol to the Geneva Convention.15

A difficult context for the EU

Despite Israel’s violations of international law, the Trump presidency has offered the country unconditional support. This approach constitutes a break from historical US policy. Since the era of the first Oslo peace accord, signed in Washington in 1993, the US had sought to act as a broker, if not an entirely neutral one, between Israel and the Palestinians. The publication of Trump’s ‘deal of the century’ for Israel and Palestine in January 2020 crystallised his administration’s policy towards the conflict: unconditional support for Israel while turning the screws on the Palestinians. The plan promises a “realistic two-state solution” while offering a one-state reality. It completely rejects the former international consensus and contravenes decades of US and EU policy – redrawing the internationally agreed 1967 borders and flouting UN Security Council resolutions and many of the provisions of the Oslo Accords. It grants the wishes of Israel’s far right, including the annexation of 30 per cent of the West Bank. It talks of a Palestinian ‘state’, but turns the West Bank into disconnected Palestinian enclaves, punctuated by Jewish settlements (see Map 1). It anoints Jerusalem Israel’s capital; and allocates far-flung eastern neighbourhoods as Palestine’s. It permanently hands over responsibility for Palestine’s external security to Israel. It sets a litany of conditions for Palestinian self-governance, of which Israel and the US are the ultimate arbiters. It also denies the right of return of Palestinian refugees. The plan has already been rejected by the Palestinians and is very unlikely to be implemented. But it will embolden Israel to push ahead with the de jure annexation of the West Bank, and could redraw the contours of any future settlement. It has also already provoked violence: mortar shells and other projectiles have been fired from Gaza, leading Israel to launch air strikes on Hamas targets; and violent clashes between protestors and the IDF have erupted in the West Bank, resulting in Palestinian casualties.

The Trump administration laid the groundwork for its plan during Mogherini’s tenure. In December 2017, the US recognised the whole of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital – prejudicing the ‘final status’ of the city. In May 2018, the US officially moved its embassy to Jerusalem. And in April 2019, just before the Israeli election, Trump recognised Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, flying in the face of international law which deems the area to be Syrian territory under Israeli occupation. Senior US officials have gradually abandoned the concept of full Palestinian statehood, and questioned the illegality of the settlements.

At the same time, Trump has sought to increase the pressure on the Palestinian side, starving it of much-needed financial support. The Trump administration has ended US support for the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The US had been the biggest donor to UNRWA – providing $368 million, or 30 per cent of the agency’s budget in 2016.16 Trump also cut all US bilateral aid to the Palestinian Authority in 2019; the year before he became president the US paid $263 million to the PA.17 In response to the Palestinian rejection of his peace plan, Trump recently cut the last source of US funding to the Palestinians, ending aid to the PA security forces from 2021 onwards. He has also closed the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s (PLO) office in Washington. As a result, the US has lost any credibility with the Palestinians as an honest broker, and the PA has broken off relations with the US.

In addition to the damaging position taken by the Trump administration, EU member-states have become increasingly divided, paralysing the Foreign Affairs Council, which takes foreign policy decisions by unanimity. Netanyahu has forged alliances with some Central and Eastern European member-states, finding common ground in particular with Hungary’s populist prime minister, Viktor Orbán (despite concerns about Orbán’s willingness to use anti-Semitic tropes for electoral advantage). He has also sought to deepen energy co-operation with Greece and Cyprus by developing plans for an Eastern Mediterranean pipeline that would transport natural gas from Israeli and Cypriot gas fields to Greece, and from there into other European countries.

Trump has sought to increase the pressure on the Palestinian side, starving it of much – needed financial support.

The Holocaust and Europe’s history of anti-Semitism have made EU member-states uncomfortable about taking a firm line with Israel. Netanyahu has taken advantage of this, claiming that European criticism of Israel, whatever its factual basis, is anti-Semitic.18

The EU’s focus on Israel-Palestine has also been eclipsed by other more pressing European concerns in the Middle East, including escalating tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, the Libyan and Syrian civil wars, the rise of Islamic State; and the ensuing migration crisis in Europe.

The growing power of Iran in the region has also made it more difficult for the EU to make progress on the Israeli-Palestinian relationship. Tehran has created a corridor running from its own territory to the Mediterranean, controlled by its proxies, which is perceived as a threat not only by Israel (which Iran has long threatened with annihilation) but also by Arab states in the region. Shared animosity towards Iran has helped Israel to normalise its relations with its historically hostile Sunni Arab neighbours, thereby relieving some of the pressure to change its policy towards the Palestinians. Arab countries recognise the security, economic and technological benefits that the relationship with Israel can provide. Netanyahu has held talks with Oman, met the Saudis and Emiratis in Warsaw, and his culture and communications ministers have both separately visited the UAE. Privately, Israel conducts backchannel diplomacy with the Gulf states.

The EU’s policy under Mogherini: Declaratory diplomacy

As a result of this unfavourable climate, the EU and European countries have largely relied on diplomatic statements of condemnation of Israeli and Palestinian actions, without imposing any substantive costs on their leaders. As High Representative, Mogherini pursued diplomatic means, trying to bring both Israel and the Palestinians to the negotiating table, but without adequately addressing the enormous asymmetry in power between the two.

Preserving the framework

Nonetheless, Mogherini’s role in defending the Middle East peace process (MEPP) framework should not be overlooked. As Israel and the US sought to unpick the international consensus, she managed to preserve the formally agreed EU position on the conflict, as well as EU funding.

However, Mogherini struggled to get the Council of the EU to agree joint statements. Instead, she was forced to make statements on her own authority or (still weaker) have her press spokesperson comment on events.

When the US recognised the whole of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017, she pushed back in public and in private. In her own statement, Mogherini confirmed that “the EU position remains unchanged”, reiterating that Jerusalem must be a shared capital for both parties.19 The limits of EU unity were revealed at the UN General Assembly when Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania abstained on a resolution to protect the special legal status of Jerusalem (the US, of course, rejected it).20 When the US moved its embassy in May 2018, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Romania blocked a statement of condemnation by the EU Foreign Affairs Council. Mogherini released her own statement emphasising the EU’s “clear, consolidated position on Jerusalem … including on the location of diplomatic representations”.21 Mogherini was, however, able to make a statement on behalf of all member-states when Trump recognised Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights just before the Israeli election in April 2019. The statement re-asserted the EU’s commitment to UN Security Council resolutions 242 and 497, which deny Israeli sovereignty over territories acquired during the 1967 war and call for withdrawal from territories occupied including the Golan Heights.22

Mogherini also managed to maintain EU support to the Palestinians. Trump cut almost all US bilateral aid to the Palestinians, but the EU kept its funding at about €1.1-1.3 billion over 2017-2020. When Trump ended support for UNRWA, the EU spokesperson released a statement that emphasised the EU’s continued commitment to the agency, and expressed regret at the US decision, later announcing an extra €40 million.23

The High Representative relied heavily on classical diplomacy in her attempt to bring the two parties back to the negotiating table. In her first year, Mogherini talked of “revitalizing” the Quartet, comprised of the UN, US, EU and Russia, which aims to facilitate Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. She also appointed Fernando Gentilini, a senior Italian diplomat, as her Special Representative to the MEPP.24 Gentilini’s main objective was to bring about peace negotiations, and his mandate included maintaining contact with all parties and persuading them to negotiate, as well as reporting to the Quartet regularly.25

Mogherini’s focus on diplomacy meant she failed to address the vast asymmetry in power.

But Mogherini’s focus on diplomacy meant she failed to address the vast asymmetry in power between Israel and the Palestinians. Israel is a state with a flourishing economy and one of the most technologically advanced militaries in the world; the occupied Palestinian territory is not yet a state, is in economic crisis and has no military. The EU attempted to persuade Israel to negotiate, and to accept the EU as a credible interlocutor, by offering assurances on security and incentives, such as a Special Privileged Partnership in December 2013 (under Mogherini’s predecessor Catherine Ashton), and additional interim incentives, proposed by the Council in June 2016. But these efforts inadvertently skewed the dynamic even further in Israel’s favour. The EU felt the need to reassure Israel, to counter Israel’s perception that Europe has a pro-Palestinian bias. At one stage, the EU came close to discussing whether to accept some settlements in the West Bank as legitimate, which was the only way Gentilini could envisage relaunching the peace process.26

Unconditional incentives for Israel

While the peace process has languished, the bilateral relationship between Israel and the EU has continued to deepen without conditions, costing the EU leverage. They have signed over a dozen bilateral agreements to supplement the overarching Association Agreement in areas including police co-operation (2018), development (2018), aviation (2013), agriculture (2012) and industry (2010). Israel participates in EU research and innovation programmes, and Israeli students can take part in the educational exchange programme Erasmus+. The EU is Israel’s largest trade partner, comprising a third of Israel’s total exports, and Israel was the EU’s 27th most important partner in 2018.27

The two main foundations of the EU-Israel relationship are the EU-Israel Association Agreement (1995) and the European Neighbourhood Policy Action Plan of 2004 (ENP). The Association Agreement provides for free trade in goods, liberalised services, institutionalised political dialogue and enhanced co-operation on economic and other matters. The ENP is a bilateral political document that seeks to “gradually integrate Israel into European policies and programmes” in areas including trade, services, energy, migration, police and judicial co-operation.

The EU does not enforce this conditionality in its agreements with Israel, because there is no political will.

Both instruments are conditional upon respect for “common values”. In the case of the Association Agreement these are the principles of the United Nations Charter, specifically human rights and democracy (article 2); and in the case of the ENP, human rights, fundamental freedoms, democracy, good governance and international humanitarian law, among others. The EU is entitled to suspend these agreements in the event of serious breaches of these values. But despite Israel’s repeated violations of some of these values, the EU does not enforce this conditionality, because there is no real pressure from the member-states to do so.

All the EU’s association agreements contain an article establishing human rights and democratic principles as essential elements (the so-called ‘human rights’ clause). Article 79 of the EU-Israel Association Agreement states that if one party fails to fulfil an obligation, the other party may take “appropriate measures” which “least disturb the functioning” of the agreement. In theory, the EU could decide to suspend the EU-Israel Association Agreement by a qualified majority, because it is an instrument of trade and not foreign policy. But in reality, this is a highly political decision. Many in the EU believe that even formal annexation of the West Bank would not be enough to persuade member-states to suspend the Association Agreement. Triggering suspension is viewed as very extreme by officials in the EEAS.28

The furthest the EU has gone was to freeze the ENP Action Plan for Israel in 2009, in response to the large number of civilian deaths caused by Israel during the 2008-2009 Gaza war: the two sides had agreed the previous year to upgrade the plan at a technical and political level. Israel then declined to attend the Association Council, the forum for political dialogue provided for in the Association Agreement, which at the time of writing has not met since 2012. Tensions with Israel became unmanageable after the EU published its guidelines on Israeli participation in EU-funded programmes in 2013, which excluded entities in the Israeli settlements from receiving EU grants and prizes.29

Disappointing on differentiation

Mogherini could have done more to build on the 2013 decision on grants and prizes, taken under Catherine Ashton. She could have pushed harder on the EU’s policy of ‘differentiation’ between Israel proper and the territories occupied after 1967. The policy, introduced in 2012, means the settlements should be excluded from all the benefits of the EU-Israel bilateral relationship, as well as the member-states’ bilateral relationships with Israel. Differentiation measures include:

- Enforcing compliance with EU rules of origin, so that goods produced in the settlements do not benefit from preferential tariffs.

- Ensuring that the EU does not recognise product certification conducted in the West Bank, meaning that products certified in settlements cannot be freely placed onto EU markets.

- Preventing research entities in settlements from participating in EU research and innovation programmes.

- Implementing labelling guidelines so that consumers can distinguish between goods produced in the settlements, by Palestinians in the occupied Palestinian territory, and in Israel proper.30

It is important that the EU distinguishes between Israel proper and the settlements for two reasons. The first is purely legal: to protect the integrity of the EU legal system by ensuring that settlements, which are illegal under international law, are not treated as though they were part of Israel. The second is political: differentiation increases the cost to Israel of maintaining the settlements. Eventually, the policy could help to alter Israel’s cost-benefit calculation.

The EU did take some significant steps on differentiation under Mogherini. As well as the guidelines issued by the Commission on the EU budget, the EU now includes differentiation clauses in all new agreements with Israel (since December 2013). In 2015, after nearly five years of internal discussions, mostly under Ashton, the Commission published guidelines on the correct labelling of settlement products,31 and in December 2019 the European Court of Justice ruled that EU member-states must label products produced in the settlements.32

In December 2016, the UN took up the policy of differentiation. This was the result of then-US President Barack Obama’s tougher policy towards Israel and the change in EU policy, alongside pressure from the UK and France (both UN Security Council members). The UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 2334, which confirmed that the settlements have no legal validity and called upon all states to distinguish between Israel and the settlements in their dealings with the country.

Mogherini could have pushed harder on the EU’s policy of ‘differentiation’ between Israel proper and the settlements.

There are many areas where differentiation is not properly implemented at the EU level, however. The EU has not yet updated its past agreements with Israel to include differentiation clauses, and EEAS officials say that there is no intention of doing so at present. Updating agreements would require approval from Israel, which would be politically difficult. According to the ‘Differentiation Tracker’ published by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), out of the EU’s existing 17 bilateral agreements with Israel, just six are fully compliant with UNSCR 2334, five partially comply, and six do not comply at all.33 Mogherini should have sent a strong message to the EU institutions to proceed with implementing the policy, as they will not move on such a politically controversial issue without being pushed.

The application of differentiation is even patchier at the member-state level. Here too, Mogherini could have been firmer in her messaging. Member-states have proved unwilling to put their bilateral relationships with Israel at risk by implementing differentiation. Only six out of the 28 member-states have actively sought to implement the policy in their domestic legislation – Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands. The ECFR found that out of 260 bilateral agreements between member-states and Israel, very few contain a clause defining the territorial scope. And where clauses are present, they are imprecise.34 Member-states are also failing to enforce labelling requirements. Recent research by the EU Middle East Project found that just 10 per cent of wines from the settlements on sale in the EU were labelled correctly (or partially correctly) by vendors in member-states.35

Unconditional assistance to the PA

Under Mogherini, the EU continued to provide financial assistance towards building a Palestinian state. But at the end of Mogherini’s tenure, Palestinian democracy and the economy were both in crisis. The EU provides assistance in order to improve governance, the rule of law, sustainable service delivery and economic development. In 2018 alone, the EU paid €155 million to support the PA and €71 million towards sustainable economic development and enhanced governance. The EU heads of mission in Jerusalem and Ramallah have said that EU support has yielded “mixed results”, “disappointment and fatigue”.36 The EU has been ineffective because it has not addressed the underlying causes of the Palestinian territory’s weak democracy and economy; primarily, Israel’s restrictive policies and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’ obduracy.

Palestinian democracy is in poor health. The Palestinian leadership is geographically and ideologically divided, with the Fatah-dominated PA in control of the West Bank, and Hamas in Gaza. The rivalry between Abbas and Hamas is deeply personal and existential: Abbas believes Hamas wants to assassinate him. Abbas has clung to power and blocked reconciliation with Hamas, weakening the Palestinian national movement. There have been no elections since 2006. The judiciary is controlled by the executive; rule is by presidential decree; the legislature is dissolved; civil society is withering, with harsh prison sentences for those critical of the Palestinian authorities; and PA security forces carry out human rights violations against Palestinians. Mogherini should have attached greater conditionality to EU assistance to the PA.

The economy is also in a critical state, expected to slip into recession in 2020-2021. The PA neared fiscal collapse in 2019 when for political reasons Israel refused to transfer Palestinian tax and customs money (clearance revenues), which account for 65 per cent of the PA’s budget, and which Israel collects on behalf of the PA. Continued uncertainty about the stand-off over clearance revenues has forced the PA into crisis management, cutting public spending and increasing borrowing from domestic banks. The economic situation has been exacerbated by dependency on international aid and the decline in donor support. The PA faces a financing gap of $1.8 billion.37 According to the World Bank, the primary cause of Palestinian economic woes is the restrictions Israel places on access, movement and trade. Political decisions by Israel, but also by the PA and Egypt, are choking economic growth. Mogherini should have ensured that EU money went hand in hand with pressure on Israel, Egypt and the PA to relax their restrictions.

Recommendations

The asymmetry between Israel and the Palestinians makes it more difficult to resolve the conflict. One way to address the imbalance would be to impose greater costs on Israel for its creeping annexation of the West Bank and the blockade of Gaza. But given the EU’s need for consensus on foreign policy, and how divided member-states are on this issue, sanctions are out of the question. The EU also needs to be firmer with the PA for blocking democratic progress and thus meaningful Palestinian representation in future negotiations. There are still some measures that the EU can take to try to create the conditions for peace.

The asymmetry between Israel and the Palestinians makes it more difficult to resolve the conflict.

1) Protect and promote internationally agreed principles

The EU has a crucial role to play in containing Trump, and in protecting the internationally agreed parameters for the peace process. Borrell must strongly reject Trump’s plan, stressing EU support for two sovereign states living in peace and security on the basis of the 1967 borders, with agreed land swaps, Jerusalem as a shared capital, and a just outcome for Palestinian refugees. Borrell should use the sense of crisis engendered by the Trump plan to push for recognition of Palestinian statehood both by EU member-states and by the UN, and for recognition of East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state.

The initial EU response to the plan was tentative and weak. Borrell issued a statement agreed by all 28 member-states, promising that the EU would “study” the US proposal in line with international law and the EU’s positions. Individual member-states issued conflicting statements. Austria, France and Poland “welcomed” the US plan. Post-Brexit Britain, unwilling to challenge the US, called it a “serious proposal”. In contrast, Ireland expressed “grave concern” and Luxembourg issued a critical statement. Borrell failed to achieve a stronger unanimous statement by the EU-27, because Hungary blocked it. In a sign that Borrell will seek ways to avoid paralysis, he put out a bolder statement on his own authority, saying that “steps towards annexation … could not pass unchallenged”.38

Some argue that the EU should not talk about the two-state solution any more, given the one-state reality that is emerging on the ground. But two states is still the most practical, just resolution to the conflict. Given current tensions and political trends, a single, democratic state with equal rights for Israelis and Palestinians is even less likely to emerge than two states.

2) Be honest about the one-state reality

The gulf between the EU’s rhetoric on the two-state solution and the increasingly visible one-state reality harms the EU’s credibility. As it stands, Israel controls almost all of the occupied Palestinian territory: only Area A of the West Bank (less than one fifth of it) is controlled by the PA, and Israel has complete control over access and movement in Gaza. In Mogherini’s own words, the situation is “a one-state reality of unequal rights, perpetual occupation and conflict”.39

The EU should clearly spell out the choices that Israel is making. Borrell should state publicly that Israel’s policies of de facto and de jure annexation are creating one state with unequal rights for two peoples. The EU should make clear that if Israel makes a two-state solution impossible, the Union will be forced to switch its support to a one-state solution of equal rights, where Israel would no longer be a Jewish majority state.

The EU, and the donor community at large, should also have a more honest conversation about what policy would be appropriate should Israel continue to develop in that direction. Mogherini signalled this in a speech at a meeting of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee (the body that co-ordinates international aid to the Palestinians) in September 2019, stating that EU support for the Palestinians is conditional upon the prospect of a two-state solution, and that “should this prospect disappear or no longer appear achievable at all, the European Union and other donors would need to fundamentally review our support”.40

3) Stop waiting for consensus in the EU

In a recent opinion article, Borrell called for Europe to ‘embrace its power’, acknowledging the Union’s foreign policy divisions and urging member-states not to use their vetoes to ‘weaken the Union’. The Council’s paralysis on the Israel-Palestine issue means that Borrell will need to find different formats and forums for decision-making on the peace process.

Coalitions of the willing, or contact groups, have proved effective on other foreign policy issues. Notable examples include the E3 (UK, France, Germany) + EU format for negotiations on the Iran nuclear deal, where the E3 commenced negotiations and were later joined by the EU. Another is the International Contact Group on Venezuela, which includes several EU member-states alongside Central and South American countries.41 Borrell could also take up French President Emmanuel Macron’s idea of a European Security Council, a small group of EU member-states plus the UK.42

Given current tensions and political trends, two states is still the most practical, just resolution to the conflict.

Where possible, Borrell should ensure that large sympathetic member-states support the High Representative’s position. He could then persuade them to influence other member-states to formulate a joint policy, or encourage coalitions of willing member-states to follow the policies outlined in this paper. Borrell should continue to support statements by groups of member-states, as Mogherini did. However, the High Representative should make sure that member-states’ policies are still discussed in the Council, so that other EU countries do not feel excluded and the institutional link between member-states’ activities and the position of the EU as a whole is not broken.

Member-states could, for instance, pursue joint legal action and compensation for the destruction of European-funded infrastructure in Area C of the West Bank. An important precedent was set in 2017, when Belgium led a group of eight member-states to write a letter of complaint to the Israeli foreign ministry, demanding compensation for the destruction of €30,000 worth of solar panels and mobile units installed in Bedouin communities in Area C. That same year, Israel announced plans to demolish and relocate the Bedouin village of Khan al-Ahmar in Area C to a location near a landfill site in East Jerusalem. Mogherini called upon Israel to reconsider its decision.43 However, this statement was not so much the result of pressure from Mogherini in Brussels, but rather from the EU5 – the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain – who released a rare joint statement.44 These countries, particularly France and Germany, engaged in aggressive behind-the-scenes diplomacy, ensuring that Central and Eastern European member-states held the line. Israel has not yet demolished the village.

4) Push on differentiation

The EU should continue to defend international law, making clear that the settlements are illegal and treating them as such. At the bare minimum, the EU and its member-states should fully implement UNSCR 2234.

Due to the fractures in the Council, it is hard for the High Representative to take any politically sensitive measures in the area of foreign policy. For this reason, Borrell’s best hope of shaping the conflict will be via his role as the Vice President of the European Commission. Differentiation can be pursued as a trade matter, where decisions are taken by qualified majority voting, rather than a foreign policy issue, where decisions are taken by unanimity.

Implementing differentiation will not require any further agreement from the member-states or the EU Commission. Borrell already has the legal basis in the form of UNSCR 2334, and the mandate from several Council conclusions since 2009, most recently in January 2016. Borrell should instruct the Commission to launch a mapping exercise to review the EU’s and member-states’ bilateral relationships with Israel – including treatment of goods and services produced in settlements – and try to bring them into line with UNSCR 2334. The EU could create a forum for member-states to exchange information on implementation and best practices. However, updating agreements to ensure they contain the appropriate territorial clauses would require agreement from Israel, which would be difficult to achieve.

The recent publication of a database of companies involved in settlement activities by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights was an important development for differentiation policy. Nine of the 112 businesses listed were domiciled in EU or former EU member-states (France, the UK and the Netherlands). The PA has announced it will pursue legal action against these companies in the relevant national courts. If updated regularly, the list could be a useful resource and add important impetus to differentiation policy.

Publicly, the external messaging by EU officials should be that the Union is simply protecting its own legal integrity by ensuring that it does not have dealings with the settlements.

Contributing to “strict observance … of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter” is one of the objectives of the EU.45 The Union must therefore conduct its relationship with Israel (and all states) in accordance with its own laws and international law. Under the EU treaties, the High Representative/Vice President of the Commission has an obligation to ensure the consistency of policies and implementation.46 The EU’s message to Israel should be that any steps taken to limit co-operation with entities in the settlements are not sanctions, but consequences of a legal and technical process. There is a live debate inside the EU institutions about whether such an approach is possible. The view of one EEAS official is that a technical approach would not fly; it would require political ownership and a political message from Borrell. But Borrell should at least explore the willingness of member-states to let him proceed.47

The Israel-Palestine conflict could be an excellent test case for the geopolitical Commission.

The EU will also have to be ready to rebut the Israeli charge that differentiation singles out Israel unfairly, that it is anti-Semitic, and that it is part of the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement (BDS).48 Israeli politicians and legal scholars have pointed to the occupation of Northern Cyprus by Turkey, Nagorno-Karabakh by Armenia and Western Sahara by Morocco, asking why the EU does not pursue differentiation in these cases. It is true that the EU has been inconsistent in its treatment of occupied territories. The EU has been much stricter with Russia than with Israel, for example. After Russia illegally annexed and occupied Crimea in 2014, the EU imposed sanctions and restrictive measures on Russia, excluding Russian entities in Crimea from the benefits of the EU-Russia bilateral relationship. In contrast, the Commission and European Parliament agreed in 2019 to include occupied Western Sahara in a fisheries agreement with Morocco, despite several rulings by the ECJ to the contrary. The solution is not to weaken measures against Israel, but to ensure fairness and consistency in the EU’s dealings with all occupied and annexed territories. The Commission could carry out a review of the EU’s relationships with such territories.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has spoken of a creating a “geopolitical Commission”. This means an increased focus on external action and a larger role for the Commission, and greater coherence in between the EU’s internal and external relations policies. The EU-Israel relationship could be an excellent test case for applying the Union’s laws and principles, as well as international law, to its relations with a close third country.

5) Communicate better in Israel

The EU needs to fight back against the anti-EU rhetoric of the Israeli government and politicians, particularly against accusations of anti-Semitism. A survey by the Israeli think-tank Mitvim found that 55 per cent of Israelis surveyed consider the EU “more of a foe,” while only 18 per cent view it as “more of a friend”.49 In November 2018, Netanyahu criticised the EU’s “hypocritical and hostile stance towards Israel”.50

The EU has stepped up its efforts to communicate the logic behind differentiation. The EU Ambassador to Israel and the Special Representative for the Middle East peace process both published opinion articles on the policy in The Jerusalem Post at the end of 2019. The two diplomats stressed that the labelling requirements are not anti-Semitic, a boycott of Israel or discriminatory.

The EU has also faced Israeli accusations of supporting terrorism. A recent study by the Israeli Ministry for Strategic Affairs alleged that EU institutions are funding NGOs that promote “Israel delegitimisation and boycotts” and terrorist organisations.51 Mogherini wrote a strongly worded response, in which she said that “allegations of the EU supporting incitement or terror are unfounded and unacceptable”.52

One former Israeli diplomat said the EU was far too polite and needed to be much more aggressive if it wanted to influence Israeli public opinion.53 An EEAS official said that the Union’s communication was too bureaucratic and focused on statistics.54 Clearly, the EU needs to work more effectively with Israeli opinion-shapers to communicate the benefits Israel gains from its relations with the EU, to stress that the EU takes Israel’s security seriously, and to counter disinformation.

6) Stop offering Israel incentives

The EU should stop offering Israel unconditional incentives and hoping that it will change course. In the domains of trade, technology and security, the EU-Israel relationship is strong. But two institutional constraints remain on the relationship – the lack of an Association Council for political dialogue, and the frozen ENP Action Plan. There are signs that both of these constraints could soon be lifted. The ENP has not been reviewed for four years, and its funding instrument will change at the end of the year when the new EU budget cycle begins. There might then be pressure on the Commission and EEAS from Israel and some member-states to revive the ENP Action Plan. And the Israeli Ambassador to the EU and the Israeli foreign ministry have been raising the issue of reviving the Association Council. If there is a new Israeli government in 2020, there will be a push by some EU member-states to ‘reset’ the relationship with Israel – particularly by most Central and Eastern European countries. The prevailing view in the EEAS is that it would be better to have political dialogue and to relaunch the Association Council, for which there is appetite among most member-states. Ireland, Sweden and France have been blocking this, however, in view of Israel’s settlement expansion.

The EU should stop offering Israel unconditional incentives and hoping that it will change course.

A revived Association Council could be a helpful forum for the EU to communicate firm messages on the peace process and settlement building. But the EU should not resume the ENP Action Plan until the conditions are met, including moving towards a two-state solution. Doing so would damage the EU’s credibility, and remove the only, albeit flimsy, conditions on the relationship.

7) Review support to Palestinian democracy

The EU should review its assistance to the Palestinians and ensure that it is supporting Palestinian sovereignty, rather than entrenching the status quo. The EU’s main tool for alleviating the Palestinian democratic deficit is to use EU aid as leverage, with both Israel and the PA. On the democracy front, both Israel and the PA are being obstructive. The PA and Hamas reached an agreement last October to hold elections in 2020; but Israel refuses to allow elections to be held in East Jerusalem, a precondition for the PA. The EU should put pressure on Israel to allow elections to be held in East Jerusalem in line with the 1995 Oslo II Accord. Israel relies on EU aid to sustain the PA: its survival is in Israel’s interests as the PA ensures relative stability in the West Bank and co-ordinates with Israel on security matters.

The EU should also review its aid to the PA. It should not allow its backing to be taken for granted. The EU has put too little pressure on Abbas for fear of his authority declining further, which could result in a collapse of the PA. In return for its aid, the EU should make three demands:

i) Abbas should take serious steps towards achieving reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, which will be vital for democracy. This would need the backing of regional powers like Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

ii) The PA should address democratic deterioration. Even in the absence of elections, the PA should reconvene the dissolved Palestinian Legislative Council (the legislative branch of the PA, which approves the government budget, the prime minister and his government) and the Palestinian National Council (the legislative branch of the PLO, responsible for forming the PLO’s policies). It should also end the use of excessive force by Palestinian security forces.

iii) The PA should not resume punitive measures on Gaza, such as cuts to the salaries of civil servants in the strip.

8) End no-contact policy with Hamas

The EU has a no-contact policy with Hamas, which it designates as a terrorist organisation. Hamas’ violent tactics and extreme rhetoric are of course unacceptable. Unpalatable as Hamas may be, it remains the dominant political and military force on the Palestinian side. Israel’s punitive policies have only served to strengthen Hamas’s influence, while weakening the PA – this is neither good for moderating Palestinian politics nor for Israel’s security. Hamas has shown itself to be capable of pragmatism when necessary.

Engagement – not recognition – could help move Hamas towards moderation, forcing the organisation to play the diplomatic game.55 There are some pragmatic voices inside the Hamas leadership that the EU could engage with. The EU should talk to members of Hamas’s Political Bureau, including its head, Ismail Haniyeh; Mousa Abu Marzouq, senior member and advocate for reconciliation with the PA; and former head Khaled Mashal. Having no contact at all marginalises the EU in discussions on the conflict and regional issues, because the Union has to rely on a third party as a conduit. It also prevents the EU from taking a direct role in intra-Palestinian reconciliation. Furthermore, engagement will be necessary if the EU wants to support Palestinian elections. The EU could offer to support reconciliation by appointing a Special Representative with a strong background in peacebuilding and reconciliation.

The 2006 election yielded a Hamas majority across the occupied Palestinian territory. Despite being deemed free and fair by electoral observers,56 the result was rejected by the EU, US and the UN secretariat, who cut off direct aid to the Palestinian government when Hamas refused to renounce violence. This policy has not been revisited since. The EU should not repeat the mistake of 2006, and should make it clear that it will respect the result of a future free and fair election. Mogherini raised the EU’s no-contact policy at two Gymnich meetings (informal meetings of EU foreign ministers, where no formal decisions are taken), but failed to follow it up.

The view in the EEAS is that having no contact is an impediment to EU involvement in the peace process, but the policy is being driven by the member-states. Central and Eastern European states and Germany are particularly opposed to it; Ireland and Spain – with direct national experience of bringing violent extremist groups into political processes – are the most pro-engagement voices. Borrell should raise the idea with the member-states regularly.

Engaging with Hamas could force the organisation to play the diplomatic game.

The EU should make de-listing Hamas as a terrorist organisation the eventual goal, setting clear targets such as the renunciation of violence and the recognition of Israel, with development aid (distinct from humanitarian aid) to Gaza conditional on each target being reached.

9) Support Palestinian economic sovereignty

The EU needs to be clearer in its messaging on the causes of the economic and humanitarian crisis across the occupied Palestinian territory, specifically Israel’s restrictive policies. By paying to alleviate the crisis without clear messaging on its causes, the EU has enabled Israel to evade its obligations under international law. Borrell should put pressure on Israel to loosen its restrictive policies. On the West Bank, the EU should urge Israel to:

i) Open internal and external crossing points, particularly to ensure access to Area C and the Jordan Valley, which are important for agriculture;

ii) Reduce road blocks;

iii) Invest in road infrastructure;

iv) Align the list of restricted dual-use items with the Wassenaar list.

On Gaza, future European financial support to the strip should go hand in hand with calls for Israel and Egypt to ease the restrictions. Mogherini and her spokesperson issued statements about periodic violence at the Gaza border, but were largely silent on Israel’s blockade. Borrell should urge Israel to:

i) Open crossings for goods and people;

ii) Increase work permits for Gazans to work in Israel;

iii) Align the list of restricted dual-use items with the Wassenaar list;

iv) Expand Gaza’s fishing zone;

v) Allow the PA access to the Gaza Marine natural gas field off Gaza’s coast, which would increase Palestinian energy independence.

The EU should capitalise on the mutual interests of the Israeli and Palestinian governments to make progress on economic issues. The PA wants to strengthen the Palestinian economy; Israel needs a stable PA and Gaza to ensure its security; and both sides have an interest in tackling smuggling in the West Bank, which leads to loss of revenue for both. The EU also has a stake in ensuring the viability of the PA; reducing Palestinian dependency on international aid; and in playing a leading role in reviving economic negotiations at a time when the political process is completely stagnant. Borrell could bring the two sides together to reopen or at least ensure the proper implementation of the 1994 Paris Protocol, which governs the economic relationship between Israel and the PA. Of course, economic progress cannot be a substitute for a comprehensive peace agreement.

Conclusion

The EU is increasingly pessimistic about the chances of resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and about the role Europe can play. The main responsibility for the failure of the peace process lies with successive Israeli governments, and to a lesser but still significant extent with the PA and Hamas. The position taken by the US has made peace even more remote. On the EU side, the lack of consensus and political will have proved a serious constraint on meaningful action. But the High Representative need not be impotent on the issue. Borrell should not neglect policies with teeth and rely entirely on diplomacy, as Mogherini did.

Borrell has a record of supporting the Palestinians during his time as Spanish foreign minister, advocating for the unilateral recognition of the state of Palestine by Spain. Whether he will be able to maintain this stance as High Representative remains to be seen, but he should certainly try to reinvigorate the EU’s efforts to bring about peace between Israel and the Palestinians. And the EU cannot simply hunker down in the hope that the Trump phenomenon disappears. Both Trump and Netanyahu may well win further terms. Another five years of EU diplomatic business as usual will allow the one-state, unequal reality in Israel to harden – to the detriment of the Palestinians, but also of Israel, which has hitherto stood out as a flawed but recognisable democracy in a region filled with authoritarian states.

2: The 1993 Oslo accords created the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a political entity to manage and control those parts of the occupied Palestinian territory that Israel would eventually withdraw from. This was intended to be the precursor to a Palestinian state. The PA derives its legitimacy from and is subordinate to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), which is an independent body and the legal representative of the Palestinian people.

3: A state annexes land by unilaterally applying its sovereignty in a territory. Annexation violates international law which does not recognise the acquisition of land through use of force (whether lawful or not).

4: Author’s private interview with Israeli official.

5: Fourth Geneva Convention.

6: Jean-Luc Renaudie, ‘Billions spent on settlements since Israel captured West Bank’, The Times of Israel, June 3rd 2017.

7: Amnesty, ‘Israeli settlements and international law’, 2019.

8: Andrew Rettman, ‘No EU cost for Israeli “apartheid” in West Bank’, EUobserver, February 1st 2018.

9: Bader Rock, ‘Middle East Update 17-23 January 2020’, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, Issue 4/2020.

10: Karen Melchior and others, ‘Demolished and confiscated structures built using EU aid in the West Bank, Question for written answer E-004526/2019 to the Commission’, European Parliament, December 18th 2019.

11: Hague Regulation 1907 IV, Article 43.

12: Yesh Din, ‘Annexation Legislation Database’, April 1st 2019.

13: Statement by Christopher Gunness, UNRWA Spokesperson, ‘UNRWA condemns neutrality violation in Gaza’, October 28th 2017; Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Cement delivered to the Gaza Strip used to build tunnels’, August 12th 2014.

14: World Bank, ‘Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee’, September 2019.

15: See Fourth Geneva Convention Articles 18, 21, 55-57, 59, and 63; Protocol I, Article 69.

16: Author’s analysis from UNRWA, ‘2016 Pledges to UNRWA’s Programmes (Cash and In-kind) - Overall Donor Ranking’, December 31st 2016.

17: Jim Zanotti, ‘US Foreign Aid to the Palestinians’, Congressional Research Service, December 12th 2018.

18: Maïa de la Baume, ‘Israel slams “shameful” EU’, Politico, November 11th 2015.

19: Statement by HR/VP Federica Mogherini on the announcement by US President Trump on Jerusalem, December 6th 2017.

20: Resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly on the status of Jerusalem, December 21st 2017.

21: Statement by HR/VP Federica Mogherini on violence in Gaza and latest developments, May 14th 2018.

22: Declaration by the HR on behalf of the EU on the Golan Heights, March 27th 2019.

23: Statement by the Spokesperson on UNRWA, September 1st 2018.

24: Remarks by HR/VP Federica Mogherini following the Quartet meeting at the United Nations, Brussels, October 1st 2015.

25: Council Decision appointing the European Union Special Representative for the Middle East peace process, April 15th 2015.

26: Author’s private interview with an advisor to the EEAS.

27: European Commission, ‘Client and Supplier Countries of the EU28 in Merchandise Trade’, 2018.

28: Author’s private interviews with EEAS officials.

29: European Commission, ‘Guidelines on the eligibility of Israeli entities and their activities in the territories occupied by Israel since June 1967 for grants, prizes and financial instruments funded by the EU from 2014 onwards’, July 19th 2013.

30: Hugh Lovatt and Mattia Toaldo, ‘EU Differentiation and Israeli Settlements’, ECFR, July 22nd 2015.

31: European Commission, ‘Interpretative Notice on indication of origin of goods from the territories occupied by Israel since June 1967’, November 11th 2015.

32: Judgment of the CJEU, Vignoble Psagot Ltd v the French Minister for Economy and Finances, November 12th 2019; Opinion of the Advocate General Hogan, Vignoble Psagot Ltd v the French Minister for Economy and Finances, June 13th 2019.

33: Hugh Lovatt, ‘Differentiation Tracker’, ECFR, October 2019.

34: Hugh Lovatt, ‘Differentiation Tracker’, ECFR, October 2019.

35: EU Middle East Project, ‘Passive enforcement: Origin indication of Israeli settlement wines on sale in the EU’, November 12th 2019.

36: EEAS, ‘European joint strategy in support of Palestine, 2017-2020’, 2017.

37: World Bank, ‘Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee’, September 2019.

38: Statement by the HR/VP Josep Borrell on the US initiative, February 4th 2020.

39: Statement by HR/VP Federica Mogherini on the ‘Regularisation Law’ adopted by the Israeli Knesset, February 2nd 2017.

40: Speech by HR/VP Federica Mogherini at the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee meeting, September 26th 2019.

41: Nathalie Tocci, ‘Europe’s just do it moment’, Istituto Affari Internazionali, October 10th 2019.

42: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘Towards a European Security Council?’, CER insight, November 27th 2019.

43: Statement by HR/VP Federica Mogherini on the latest developments regarding the planned demolition of Khan al-Ahmar, September 7th 2018.

44: Joint statement by France, Germany, Italy, Spain and UK on Khan al-Ahmar, September 10th 2018.

45: Treaty on European Union, Article 3.

46: See Treaty on European Union, Article 21(3) and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 7.

47: Author’s private interviews with EEAS officials.

48: BDS is a Palestinian solidarity movement that calls for a boycott of Israel (not just the settlements but Israel proper) until it meets its obligations under international law. In 2017, Israel passed Amendment No. 28 to the Entry Into Israel Law, which prohibits entry to any foreigner who advocates BDS on Israel or “any area under its control”, i.e. the settlements.

49: Mitvim, ‘Israeli Foreign Policy Index’, 2018.

50: ‘Netanyahu urges EU to end its “hypocritical and hostile stance” toward Israel’, The Times of Israel, November 1st 2018.

51: Israeli Ministry of Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy, ‘The Money Trail: The millions given by EU institutions to NGOs with ties to terror and boycotts against Israel’, May 27th 2018.

52: Noa Landau, ‘EU blasts Israeli minister: You feed disinformation and mix BDS, terror’, Haaretz, July 17th 2018.

53: Author’s private interview with former Israeli official.

54: Author’s private interview with EEAS official.

55: Clara Marina O’Donnell, ‘The EU, Israel and Hamas’, CER working paper, April 2008.

56: See National Democratic Institute, ‘Final report on the Palestinian legislative council elections’, January 25th 2006; Carter Center International Observer Delegation to the Palestinian Legislative Council Elections Statement, January 2006.

View press release

Download full publication

Beth Oppenheim, research fellow, CER, February 2020