Containing NATO's Mediterranean crisis

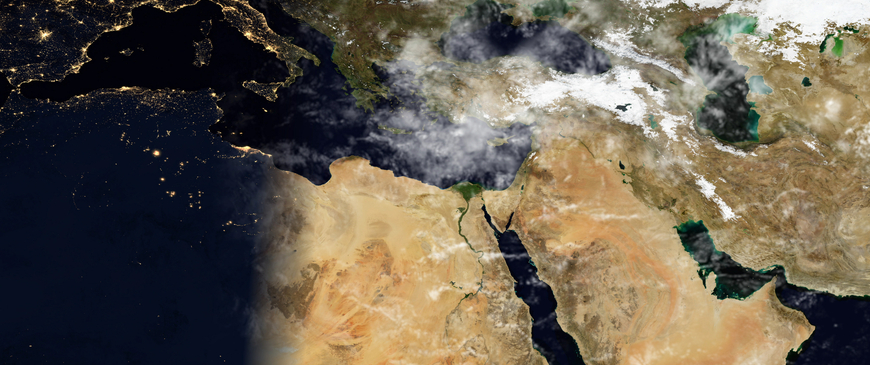

NATO’s southern neighbourhood in the Middle East and North Africa has become a hotbed of instability, and Turkey’s unilateral actions have fuelled tensions that are undermining the alliance’s cohesion. Europe and the US will have to devote more attention to the region.

“America is back”, US President Joe Biden stated in his recent address to the Munich Security Conference, in which he formally recommitted the US to defending its allies if they were attacked. This was a reinvigorating moment for NATO, after Trump cast doubt on the US’s commitment to collective defence during his tenure. However, the alliance still faces many challenges. While the questions of how to deal with Russia and China are the most prominent, NATO also faces a complicated picture to its south. Widespread instability in the Middle East and North Africa and tensions between Turkey and other allies are undermining the alliance’s cohesion and its ability to address common challenges.

The recent agreements to normalise relations between Israel and some of its Arab neighbours are the only bright spots in the region. In Syria the conflict is still smouldering, ten years after it started. While Islamic State (IS) has been defeated for now, the country has been devasted and there is little sign that the Assad regime intends to relax its grip on power. Russia has become entrenched in Syria, allowing Moscow to project its power in the Mediterranean more easily. Iran has also been able to strengthen its influence in Syria and to reinforce lines of communication between itself, militias aligned with it in Syria and Iraq, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. In Syria’s north, the last remaining rebels, dominated by extremists, control a small sliver of territory but could be forced out by a new Assad offensive, pushing millions of refugees towards Turkey. The situation in Iraq, where NATO has recently expanded its training mission, remains very unstable, with Iranian-aligned militias wielding large influence and often carrying out attacks against US and other international forces. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic – combined with discontent at the dysfunctional governance and corruption that helped spawn IS in the first place – could breed extremism once again.

Meanwhile, Libya has been in a state of civil war since the summer of 2014. The conflict has been stoked by a regional competition for influence between Turkey and its rivals, Egypt and the UAE. Turkey has supported the Tripoli based UN-backed government in Libya’s west, while Egypt, France, Russia and the UAE, have backed its opponent, warlord Khalifa Haftar. The situation has stabilised somewhat since last year, with a ceasefire and the formation of a new government of national unity, but foreign forces that were supposed to be withdrawn remain entrenched in Libya. Worryingly for NATO, Russia has become an influential player and aims to consolidate its presence in Libya. Libya’s new government is very weak, as its leaders are relatively unknown without a substantial power base of their own. It will be very challenging to hold elections by the end of the year as planned.

NATO allies will have to work closely together if they are to help stabilise Iraq, Libya and Syria.

NATO allies will have to work closely together if they are to help stabilise Iraq, Libya and Syria. But internal cohesion is precisely what the alliance lacks. In the past year there have been growing tensions between Turkey and the US, and between Turkey and European allies in the eastern Mediterranean. US-Turkey relations are at a low point. Unlike Trump, the Biden administration has sharply criticised the Turkish government for its crackdown on political opponents, but the bigger issue is Ankara’s purchase of the Russian S-400 air defence system, which led to its suspension from the F-35 fighter programme and to US sanctions on Turkey’s defence procurement agency in December 2020. From Turkey’s perspective the key issue is ongoing US support for the Syrian Democratic Forces, dominated by the Kurdish YPG, which Turkey sees as an integral part of the Kurdish PKK terrorist group.

At the same time, disputes over maritime boundaries, partly linked with the desire to exploit the region’s gas resources, have led to a sharp rise in tensions in the eastern Mediterranean. Ankara has unilaterally sought to advance its claims, sending exploration vessels escorted by military ships into disputed waters near Greece and Cyprus. In response, Greece mobilised its navy and France sent ships to the region, seeing this as the best way to deter Ankara. The dispute in the eastern Mediterranean became connected with the conflict in Libya when Turkey signed a maritime delimitation deal with the Tripoli government in late 2019, which ignored the exclusive economic zones generated by several Greek islands. Worried by Ankara’s foreign policy, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece and the UAE banded together in an informal club to counter Turkey. This in turn made Ankara feel surrounded, spurring it to become even more assertive.

Tensions have been dangerously high, with a confrontation between a French ship and a Turkish one and a collision between a Turkish ship and a Greek one. The EU has condemned Turkey’s actions as violations of Greek and Cypriot sovereignty and has imposed some largely symbolic sanctions on Turkey. But member-states remain divided over policy towards Ankara, with Germany, Italy, Spain and others favouring a soft line, thinking that Turkey is too important strategically and economically to alienate, and concerned that sanctions might not change its policy. In early 2021, Turkey halted its exploration activities in the Mediterranean and there have been some talks between Ankara and Athens. However, the situation remains prone to flaring up and Turkey has turned its attention to Cyprus, where it has pushed for a two-state solution, arguing that a single state for Greek and Turkish Cypriots cannot work, incurring international criticism as a result.

Disagreements between Turkey and other NATO members will make it harder to contain Russian and Iranian influence in the region, and to stabilise Libya, Syria and Iraq.

Disagreements between Turkey and other NATO members will make it harder to contain Russian and Iranian influence in the region, and to stabilise Libya, Syria and Iraq, countries in which Turkey wields significant influence. Disagreements in the Middle East also risk undermining NATO’s cohesion more broadly. Differences over policy towards Syria were the reason why for some time Turkey vetoed NATO plans to defend the Baltic states. And it was Turkey’s intervention to dislodge the YPG from the Syrian border in October 2019, without consulting its allies, which prompted French President Emmanuel Macron to call NATO "braindead", annoying many other members of the alliance.

Whether tensions can be eased depends on how effectively the US, Europeans and Turkey can build on the current fragile détente. US-Turkey relations are unlikely to improve much, even though Ankara says it wants better relations. The US may end up imposing a very large fine on Turkish state-owned Halkbank, accused of evading sanctions on Iran, if it is found guilty in a forthcoming trial. Other US-Turkey disagreements will also persist. Washington has stated it wants Turkey to give up the S-400, and its sanctions are meant to remain in place until Turkey gets rid of it. It will also be difficult to reduce US-Turkey friction on Syria, as long as the US continues to support the YPG, seeing this as the only way it can maintain some leverage in Syria and counter IS and Iran. Nevertheless, tensions over the S-400 and Syria could be contained. Washington is unlikely to impose more sanctions on Turkey unless Ankara activates the S-400 system or buys more equipment from Russia. And if Ankara committed to not activating the system, and was willing to accept a robust system to verify non-use, the dispute could ease. The US could try to mitigate friction with Turkey in Syria by trying to involve Kurdish groups aligned with the Iraqi Kurdish Regional Government, which have decent relations with Turkey, more deeply in the framework of the Syrian Democratic Forces coalition. Washington could also try to reduce tensions with Ankara in Syria and Iraq by trying to co-operate in containing the influence of Iranian militias. Even if this happens, however, Syria will probably remain a significant irritant in US-Turkey relations.

Whether tensions can be eased depends on how effectively the US, Europeans and Turkey can build on the current fragile détente.

Tensions between Turkey and the EU are unlikely to substantially worsen so long as Turkey refrains from further unilateral actions in the eastern Mediterranean. Although the EU might add some officials to its existing sanctions list, there is little appetite amongst member-states to impose economic sanctions on Turkey. The EU can try to engineer a more constructive relationship with Ankara, although this won’t be easy. In December, European leaders said that if Ankara showed "readiness to promote a genuine partnership with the Union", they would put forward a co-operation agenda centred on modernising the EU-Turkey customs union and reaching a new long-term agreement to care for the nearly four million Syrian refugees in Turkey. Opening negotiations on modernising the customs union could inject a new and more positive dynamic in Turkish politics and EU-Turkey relations. The proposed upgrade would require Turkey to undertake significant changes, for example to its public procurement rules, that could help drive political reform. But disagreements between member-states will make it difficult for the EU to open talks, particularly if Ankara does not take substantial steps to improve its human rights record. Realistically, the most the EU can probably do is offer Turkey a new multi-year agreement to help it support the refugees it is hosting.

If tensions between Turkey and other allies eased significantly, it would be easier for NATO allies to work together in stabilising the region. Turkey can play an important role in countering Iranian influence in Iraq, where the two are rivals. In Libya the key difficulty is that Turkey has little reason to remove its proxies if this will allow its adversaries to take advantage. But if the ceasefire were guaranteed by a robust monitoring mission or a peacekeeping force, there would be fewer reasons for Ankara to keep forces in Libya. The UN is working on a light-touch ceasefire monitoring mission, but this is unlikely to be sufficient. European allies, Turkey and the US should press for a more robust peacekeeping effort, which would also contribute to stabilising Libya more broadly. If Libya became more stable, and each side was assured that the country would not fall into the exclusive control of its adversaries, this would also dampen regional competition between Turkey and France, Egypt and the UAE.

Turkey’s next moves will be crucial in determining whether tensions can be eased. Ankara’s recent statements that it wants better relations with the EU and the US are positive signs. Easing tensions with its NATO allies would have a positive impact on Turkey’s ailing economy, providing a strong incentive to pursue a moderate course. However, this risks undermining President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s alliance with his ultranationalist partners, on which he depends electorally. At the same time, easing tensions with the West would not necessarily win Erdoğan any new voters in the 2023 election, as many moderate voters are unlikely to vote for him anymore. Therefore, it will be tempting for Ankara to keep tensions in the eastern Mediterranean simmering, while trying to avoid significant damage to the economy or a rupture in relations with the EU and the US.

This outcome would continue to undermine NATO’s cohesion. But it could still be avoided. Last year, the expectation that president-elect Biden would be firmer towards Turkey, together with the weakness of its economy, prompted Ankara to halt its exploration for hydrocarbons and reduce tensions. Continuing engagement by Washington and firm co-ordinated messaging towards Ankara by the US and Europe, combined with assistance to help Turkey care for refugees and with renewed efforts to work with it in the Middle East, could help to steer Ankara away from unilateral actions and strengthen NATO’s cohesion.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment