Why young people are right to fear Brexit

Even Brexiters admit that there will be short-term economic costs to leaving the EU. Young people would disproportionately bear the brunt, and the effects would be long-lasting.

There is a deep generational divide over next week’s EU referendum: 18-34 year olds want to remain by 61 to 22 per cent, whereas two-thirds of Britons over the age of 55 would like to leave. Young Britons tend to believe the economic consensus that Brexit would be bad for the economy, and expect that they would bear more of the costs. They are right.

It is difficult to predict how much unemployment would rise after a vote to leave the EU – but a majority of economists think Brexit would lead to a near-term shock. The British Treasury forecasts that joblessness could rise by 520,000-820.000. That would mean the unemployment rate rising from just under 5 per cent now to between 6.5 and 7.3 per cent – lower than the post-crisis peak of 8.4 per cent, but still significant. But short-run forecasts of the economy’s response to a shock are rarely accurate, and the figure might be higher or lower than this.

However, we can be more precise about who will bear the costs of a recession and the subsequent rise in unemployment. Economists know a good deal about the impact of recessions on different social groups: the young and the old, say, or the high-skilled and the low-skilled. They have also studied how recessions impact the future earnings of these groups after the economy returns to normal. And the verdict is clear. It is the young and the low-skilled who suffer the most.

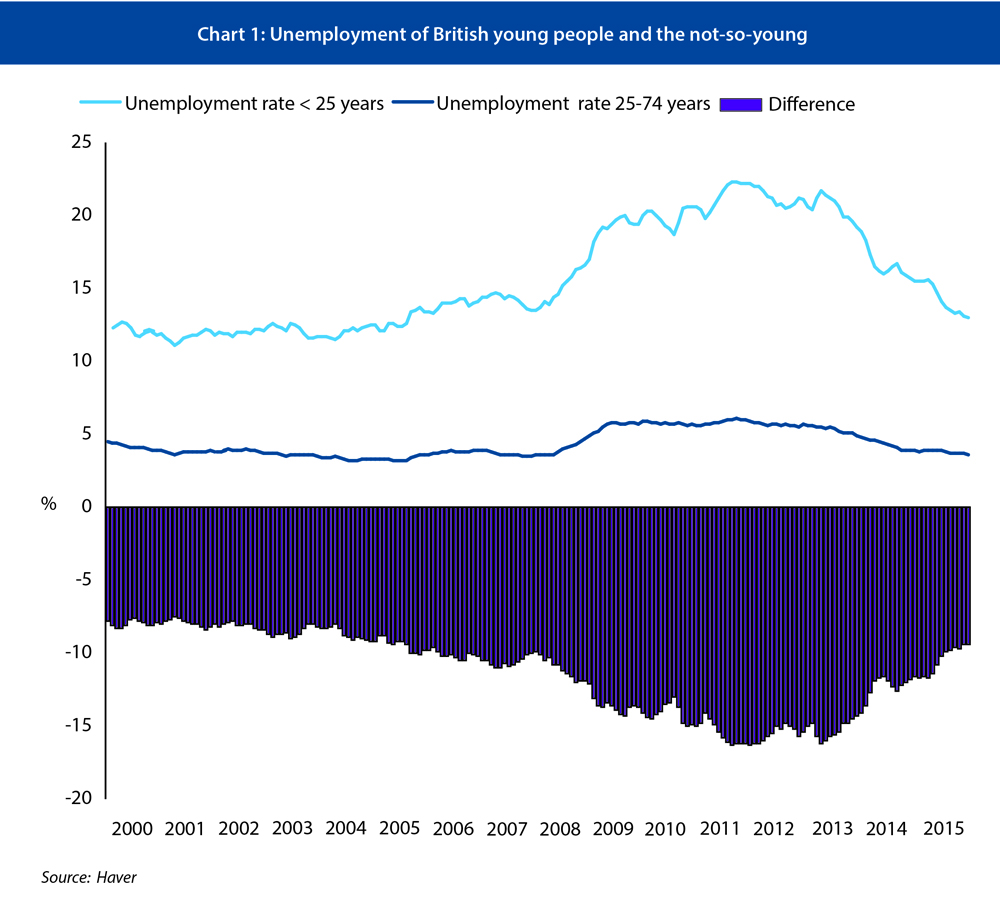

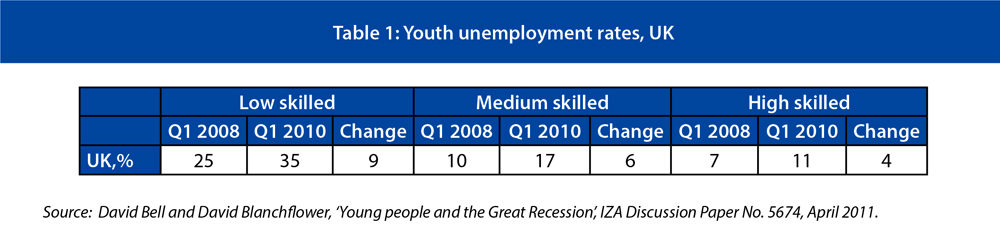

After the 2008 crash, youth unemployment rose to 22 per cent in Britain, while the unemployment rate of people aged over 25 peaked at just 6 per cent. And the gap between the unemployment rates of the young and the not-so-young doubled (see Chart 1). In general, recent research has found that for every 1 per cent increase in the adult unemployment rate, the rate for the young rises by 1.8 per cent. And low-skilled young people were also disproportionately hit by the weak labour market after 2008 (see Table 1).

Notes: 'Low skilled' refers to people with pre-primary, primary or lower-secondary education; 'Medium skilled' includes upper-secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary level of education; 'High skilled' means tertiary education.

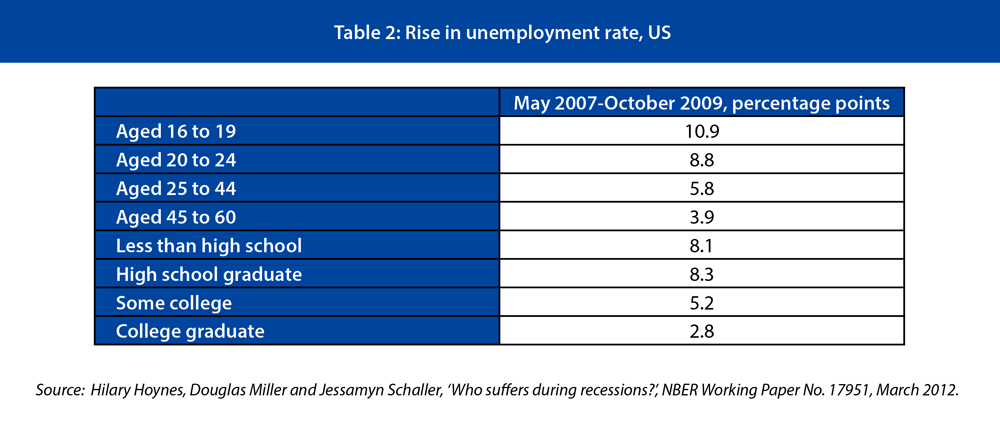

This is not specific to the UK. The US labour market reacts to recessions in a similar way (see Table 2). In the most recent recession, particular groups bore the brunt of higher unemployment, and the gap between less- and well-educated young people was particularly striking: young people with a high school degree were much more likely to be unemployed than those with a degree.

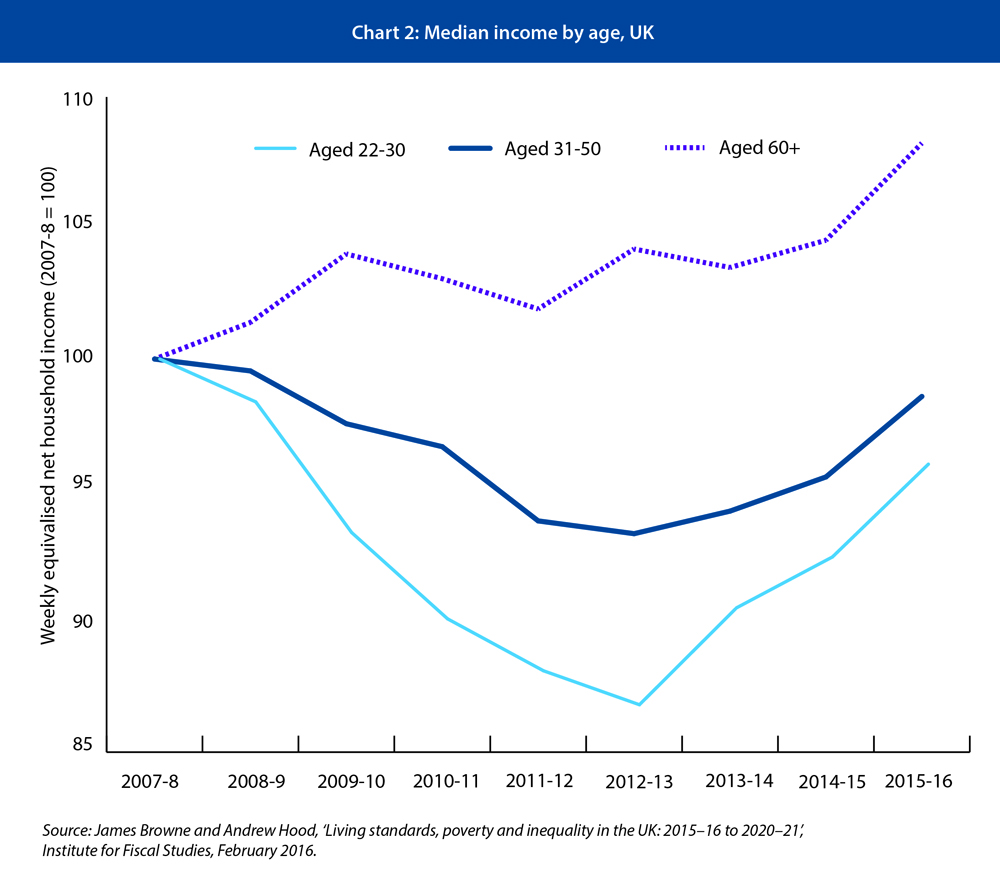

Unemployment has depressed the incomes of young people by far more than those of older workers. Britain’s Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has calculated that young Britons’ incomes are still lower than they were in 2007-8, while the generation aged 60 and over has seen their incomes increase by nearly 10 per cent.

The young and low-skilled, then, would be most badly hit in the immediate aftermath of a Brexit – and the pain would persist. Entering the labour market in stormy economic conditions has long-lasting effects on income and employment.

The young & low-skilled would be worst hit in the aftermath of a #Brexit & the pain would persist

Research on Canadian graduates has shown that, on average, graduate entrants to the labour market in a recession earn 9 per cent less than those who started work in a buoyant economy, and their earnings are still 4 per cent lower after five years. Researchers studying a recession in the US in the early 1980s found even stronger effects that lasted for 20 years. Over a lifetime, the income losses of graduating in a deep recession amounted to $75,000.

Most independent research shows that, outside the EU, Britain would lose out economically – unless it remained in the EU’s single market, which would be politically difficult. But even if one waves away the long-run impact on the British economy, it is harder to argue that there would be no short-term disruption. Indeed, Pro-Brexit economists like Andrew Lilico and Gerard Lyons agree.

We should not take the Treasury’s unemployment estimates as gospel: forecasting the size of the short-run effects of Brexit is difficult. But, as a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the research above, the Treasury’s Brexit unemployment forecast would translate into a rise in youth unemployment of between 2.9-4.3 percentage points. The young are right to oppose Brexit: they will pay the biggest price.

Christian Odendahl is chief economist and John Springford is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment