China's European charm offensive: Silk Road or Silk Rope?

The UK should not imagine that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s October visit means it now has a 'special relationship' with China. The visit was just part of a Chinese charm offensive aimed at the EU.

Xi Jinping’s state visit to the UK from October 20th-23rd had every possible element of flattery and friendship. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, said before the visit that the UK was China’s “best partner in the West”. Xi told a joint session of Parliament that China and the UK were becoming “an interdependent community of entwined interests”.

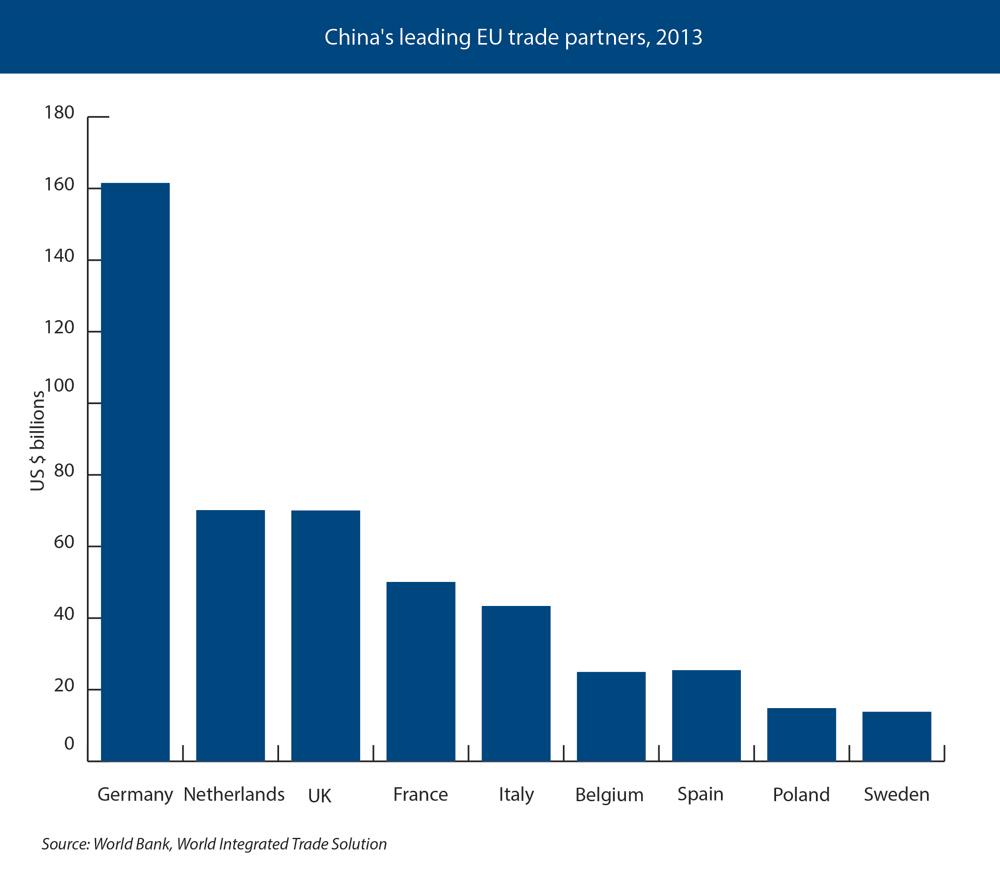

China has not, however, singled out the UK for special favours. Chart 1 shows that (even though the UK's trade with China has increased significantly in recent years) Britain is still far from being China’s most important economic partner in Europe.

China is cultivating many European countries: since September 1st 2015, Chinese leaders have met senior representatives of more than 20 EU member-states, as well as at least four European commissioners. That outstrips the amount of senior contact between the US and its European partners over the same period.

Since Sept 1, #Chinese leaders have met senior representatives of more than 20 #EU member-states

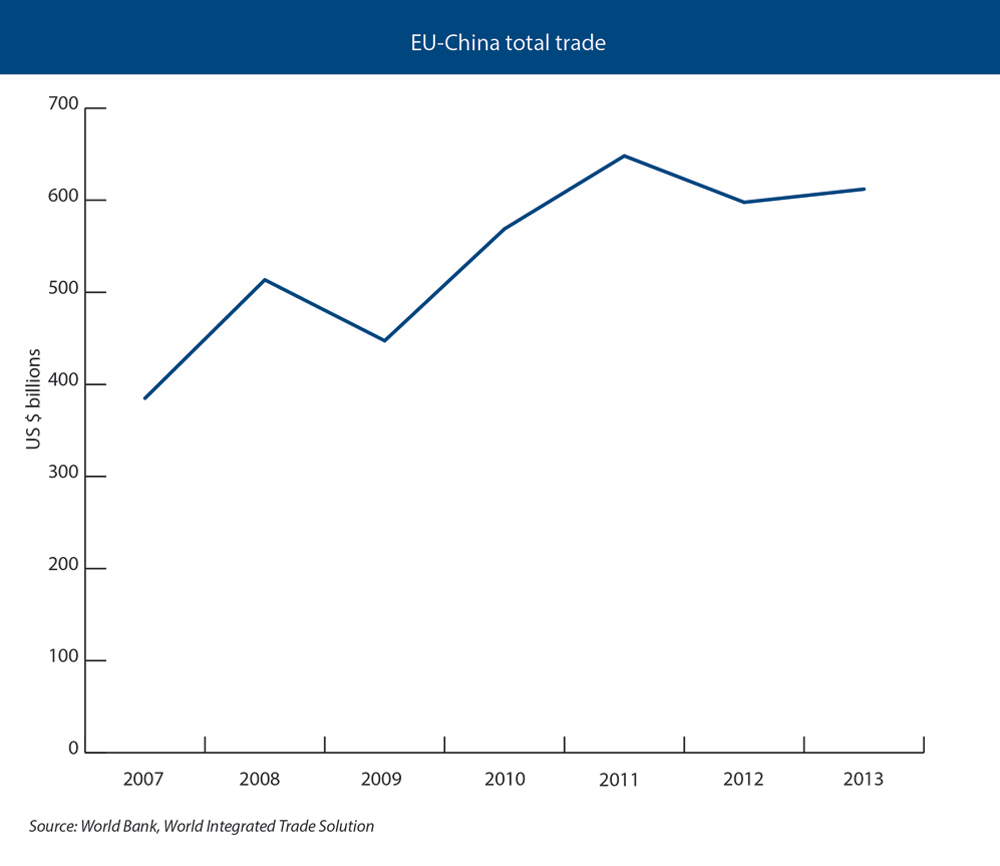

Part of China’s motivation is clearly economic. The EU is China’s largest trading partner (and China is the EU’s second largest trading partner after the US). After decades of fast growth, trade has stagnated since the eurozone crisis began in 2010 (Chart 2). Although Beijing wants its future economic growth to be founded upon domestic consumption more than investment and exports, Chinese experts privately admit that the restructuring needed for this would cause economic dislocation, threatening political stability; better to find new markets or increase exports to existing ones.

The search for markets also motivates Xi Jinping’s signature ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) initiative – designed to create the infrastructure for new land and sea routes between China and Europe (the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ respectively). Large infrastructure projects – whether railways in Central Asia or port facilities around the Indian Ocean – would help China deal with over-production of steel and other products without closing plants and creating unemployment.

According to a recent report by the Mercator Institute for China Studies and Rhodium Group, China’s annual investment in EU member-states went from virtually zero in the mid-2000s to €14 billion in 2014, with the stock of investment reaching €46 billion. The report projects that the pace of investment will continue to increase. For the EU, the prospect of China investing some of its $3.5 trillion foreign currency reserves in European infrastructure is extremely attractive. The EU-China Summit in Brussels in June agreed to "support synergies" between the Investment Plan for Europe (also known as the Juncker Plan) and OBOR. The Juncker Plan is intended to generate investments of €315 billion over three years, including in infrastructure; China envisages the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) having $100 billion to put into OBOR-related projects, and has set up a separate $40 billion Silk Road Fund to invest in businesses along the route. The two sides subsequently agreed that the European Commission, the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the Silk Road Fund would identify by December how exactly China could co-operate with the Juncker Plan.

Potentially, economic co-operation between Europe and China on Silk Road projects could indeed be "all-win", as Chinese leaders describe it. Transit times for goods and agricultural products could be shortened. Central Asian states that have developed little (the hydrocarbon sector aside) since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 could be connected to global markets. And Europe itself could use Chinese money to boost growth.

The question is whether OBOR is a purely economic project, or has geopolitical overtones. The Chinese are certainly at pains to deny that they have ulterior motives in promoting OBOR. But not everyone is convinced.

Beijing has sought to allay Russian fears that the Chinese are making a move into Moscow's back-yard. When they met in Moscow in May, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping agreed to co-ordinate the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (whose members include Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, with Tajikistan to come shortly) – even if neither the Russians nor the Chinese know how exactly to merge two very different concepts. For China, however, a good relationship with Russia is important primarily because it removes a potential obstacle on the road to Europe.

For at least some Chinese officials, the relationship with Europe is seen through the prism of China’s competition with the US: European participation in the AIIB is a good thing not only because European countries will contribute to the bank’s capital, but because they defied US opposition to join it. The fact that the UK was the first to break ranks, risking its ‘special relationship’ with the US to win a ‘golden era’ with China, may be seen in Beijing as a significant victory. And the OBOR initiative, which China claims will include 65 countries with a total population of 4.4 billion, may have two other benefits for China.

First, it may serve as a partial counterweight to two US-promoted free trade agreements, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP – 12 countries, 800 million people) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP – the EU and the US, 820 million people). TPP and TTIP are designed in part to ensure that Western countries rather than China set future global trade standards. If China embeds itself in the economies of members of TTIP or the TPP, it can encourage those countries to look after China’s interests.

Second, it may reduce the incentives for Europe to stand up to China over its claim to the South China Sea: if goods can be transported from East Asia to Europe in larger quantities and more quickly by land than by sea, the importance of the South China Sea to Europe as a trade route would shrink. And then, why put the relationship with Beijing at risk for little practical advantage?

More broadly, China can play member-states off against each other (the Chinese have told countries from Latvia to Spain that they can host the European terminus of the Silk Road), or against the US, to gain international influence. American officials may now admit privately that the US was wrong to try to persuade its European partners not to join the AIIB; but some Europeans regret that the UK chose to move first and on its own to sign up to the Chinese plan, rather than in co-ordination with the rest of the EU. In so doing, the UK gained bilaterally but weakened Europe’s ability to extract concessions from China on the AIIB’s standards of governance and transparency.

Beijing uses the lure of economic co-operation to discourage European criticism of China's human rights record. Perhaps the scale of Germany’s economic relationship with China means that Beijing cannot object when the Germans raise their concerns; during her visit to Beijing in October, Merkel held a private meeting with human rights activists and dissidents. But China makes life difficult for other European countries when they take too much interest in human rights (relations with Norway have not recovered from the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010). Those who prioritise commercial interests, on the other hand, are rewarded: the Chinese state media praised Osborne for not confronting China over human rights, and Cameron was able to claim that up to £40 billion of trade and investment deals had been done as a result of Xi Jinping's visit.

No use @eu_eeas & @EU_Commission delivering tough msgs to #China if member-states undermine #EU line

The EU needs a strategy to benefit from China's economic strength without losing sight of Europe's interests and values:

- The most important thing is to have a unified European policy towards China, which takes account of the EU's interest in preserving the global order and principles like freedom of navigation. It is pointless for the European External Action Service and the Commission to deliver tough messages, if individual member-states undermine the EU line in order to gain commercial advantage. Germany shows that it is possible to deliver unpalatable messages to China, as long as the trading relationship is important enough to Beijing; and the collective EU trading relationship is the most important of all.

- The Commission and the European External Action Service should ensure that they have a coherent approach to the OBOR initiative, ideally with one senior figure looking at both its technical aspects and geopolitical implications.

- Europe needs to remember that China is not its only partner in the region. Countries like Japan, South Korea and Vietnam are also important, politically and economically, and have their own interests; the EU should weigh these against its desire to gain Chinese approval and economic benefits.

- The EU should make clear to China that European interests in the South China Sea go beyond free passage for European shipping; the principles of maritime law at stake there have global implications. The EU is right to stay neutral on the substance of claims, but it should back the Philippines in saying that an international tribunal is the right body to adjudicate between claimants.

- The EU should offer advice to ASEAN on practical matters like maritime surveillance and fisheries management in the region, as a way of removing some of the sources of possible clashes.

- China and its neighbours need a multilateral dialogue on the South China Sea. The EU should build on the precedent of the Asia-Europe foreign ministers’ meeting in Luxembourg on November 5th and 6th, where EU ministers discussed the South China Sea in private with counterparts from all the littoral states, including China.

- The EU should revive efforts to co-ordinate policy towards China with the US. Then-US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and then-EU High Representative for foreign policy Catherine Ashton issued a statement on the Asia-Pacific region in 2012, setting out a number of shared objectives and calling for regular high-level dialogue; but there has been little subsequent follow-up. The interests of Washington and Brussels will not always coincide, but often they will, whether it is on protection of intellectual property rights, compliance with WTO standards or freedom of navigation.

- The EU should make sure that it focuses on getting China to meet European standards of economic governance and investment protection, rather than relaxing its standards to attract the Chinese to Europe: no Chinese company should be able to flout EU rules in the way that the Russian gas company Gazprom was able to for many years.

No #Chinese company shld be able to flout #EU rules in the way that #Gazprom was able to for years

The UK should not start acting as China's champion in Europe; but it should pay attention when Xi says that the UK "as an important member of the EU" should play "a more positive and constructive role" in the development of EU-China relations; if the US and China are both urging the UK to remain an active EU member, they must have good reasons. As a state with global political, security and economic interests, Britain should work with partners (particularly Germany, still the member-state with the greatest clout in Beijing) to build a more coherent EU policy towards China. An economic Silk Road between China and Europe could be a boon to both; but the EU should avoid being politically bound to China with a silk rope.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.