The European Parliament elections: A sharp right turn?

Right-wing forces are set to make sizeable gains in the European Parliament elections. That will tilt the Parliament right on many issues and could give these parties momentum nationally.

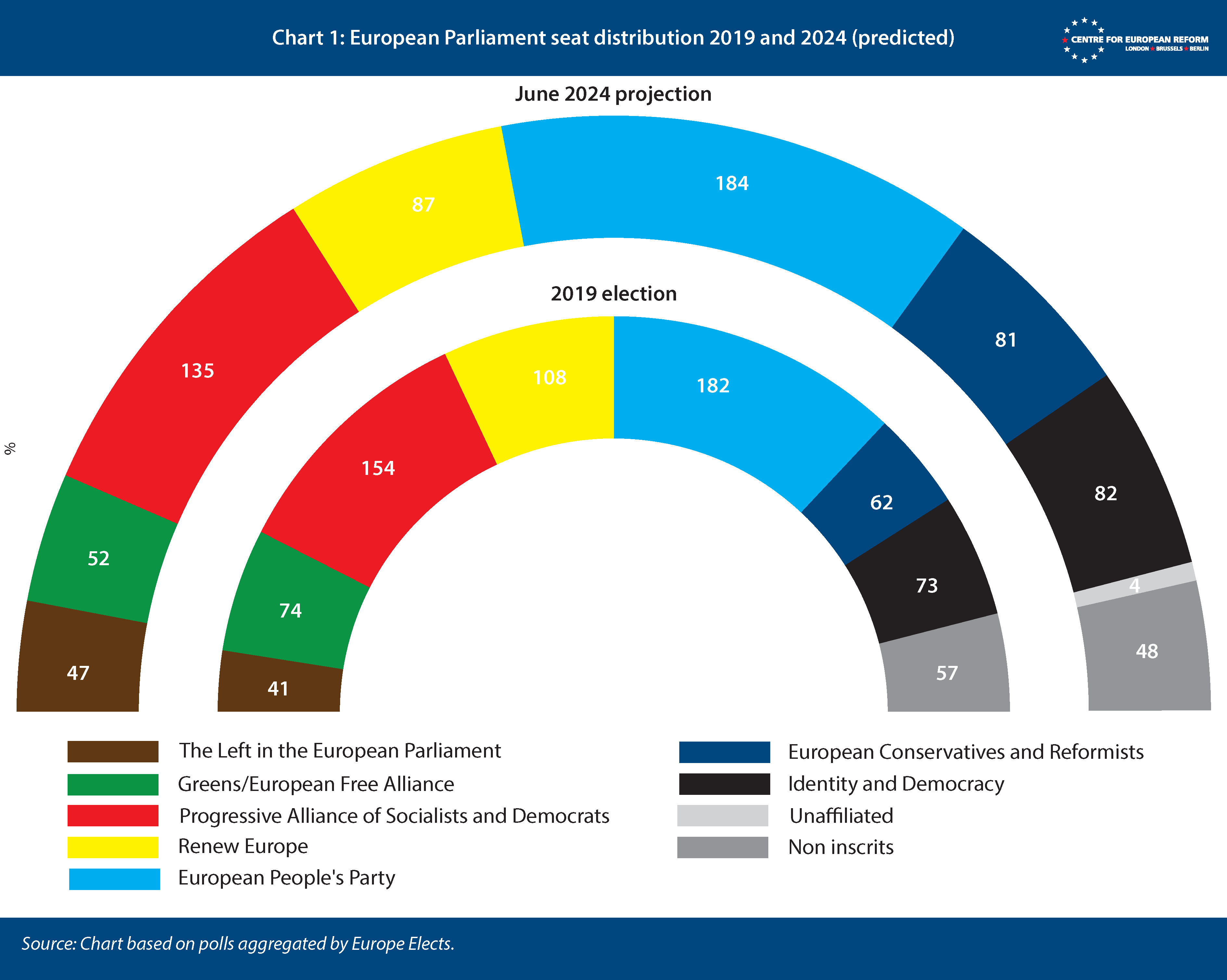

If the polls are accurate, the European Parliament (EP) elections in June will see a surge of support for right-wing populist and far-right parties. The combined strength of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) and the Identity and Democracy Group (ID) is predicted to rise from 135 to 163 out of 720 seats.

Such a result would not lead to them dominating the EP or dictating its legislative agenda. The parties within the current ‘grand coalition’ of conservatives, socialists and liberals are likely to lose a substantial number of seats but maintain their overall majority. Furthermore, the parties to the right of the conservative European People’s Party (EPP) are split in two groups. The ECR group is made up of populist nationalist parties such as Poland’s Law and Justice (PIS), Italy’s Brothers of Italy and Sweden’s Sweden Democrats. Many of these parties have led or been part of governments in their member-states. They are very critical of the EU and oppose further integration but have become attuned to working within the Union's rules. They are deeply engaged in the workings of the EP and have successfully shaped legislation, for example on the removal of online terrorist content or hindering the use of cryptocurrencies for illegal purposes. The foreign policies of ECR parties are, broadly speaking, within the mainstream. For example, the two largest parties, PiS and Brothers of Italy are Atlanticist and hawkish on Russia.

The parties within the current ‘grand coalition’ of conservatives, socialists and liberals are likely to lose a substantial number of seats but maintain their overall majority.

The ID group, which includes Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), Italy’s Lega, France’s Rassemblement National (RN), the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom (PVV) and Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ), has a rather different DNA and is essentially a far-right grouping. The two largest members, the AfD and the RN, have never been in government and are shunned by the mainstream in their respective countries. The attitude of ID group members towards the EU is generally hostile. For example, the AfD still openly talks about leaving the Union, while the RN’s approach to the EU would amount to a soft exit and would gut the Union from within. The ID group often plays the role of disruptor within the EP’s workings, with very little constructive engagement. Moreover, the foreign policy of ID members tends to be much less mainstream, very often with overt pro-Russian sympathies.

These different stances, combined with bilateral spats between ECR and ID members, make formal co-operation between the two groupings very unlikely and will reduce their influence. For example, there have been tensions between Brothers of Italy and the RN over their stance towards the EU. The influence of the right-wing contingent of MEPs is likely to be further reduced by the internal fragmentation within ECR and ID. Analysis of voting patterns by Politico suggests that they are the most internally divided party groups. The ID group is more of a loose container than a party and did not even produce a common manifesto for the elections. There is little sign that this fragmentation between ECR and ID, and within the two groups, will lessen in the next parliamentary term.

Despite this, the predicted right-wing surge will still have a substantial impact on the EP and on European politics more broadly. It is national governments, not MEPs, that appoint Commissioners. But the next Commission President nominee, whether it is Ursula von der Leyen or somebody else, may find it harder to gain the votes of an absolute majority of MEPs required for election. In 2019 von der Leyen made it through the process with only a handful of votes to spare because some MEPs from groups nominally supporting her did not vote for her. She, or another nominee, may well face the same issue again. That could push them to reach for additional votes beyond the grand coalition parties into the Greens, or the ECR. Notably, von der Leyen seems to have chosen the latter path and is openly courting the support of Brothers of Italy. If she secures it, it will mark a broader process of normalisation of substantial parts of the ECR, who have gradually moved closer to the mainstream. That process is likely to continue after the elections, spearheaded by Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the Brothers of Italy.

A stronger presence of populist right and far-right parties in the EP, combined with a weaker left, will matter both directly, because of the change in the composition of the Parliament, and indirectly, because a strong electoral result is likely to lend more momentum to such parties at the national level. Austria is due to hold national elections before the end of October this year. A strong showing by the FPÖ in the EP election could set it up for victory in the national vote. If FPÖ leader Herbert Kickl becomes Chancellor, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Slovakia’s Robert Fico would be joined by a third Ukraine-sceptic populist leader. In France, Marine Le Pen looks set to humiliate President Emmanuel Macron, undermining his authority and further normalising the RN before France’s 2027 Presidential election.

Delving into individual policy areas, a right-wing surge would influence the future of the EU’s climate efforts launched with the Fit for 55 policy package, which aims to reduce carbon emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 (relative to 1990 levels). Some measures in the policy package have already provoked protests by groups that are adversely affected by it, especially farmers. The package has also sparked broader concern among many European citizens who worry that climate action will be costly for them – for example in terms of higher energy prices or of costly renovations to make their homes more energy efficient. ECR and ID parties have latched onto this sentiment and, while not necessarily opposed to climate adaptation efforts per se, have attacked the EU’s measures as too onerous and bad for employment and growth.

A right-wing surge would influence the future of the EU’s climate efforts launched with the Fit for 55 policy package.

Implementing Fit for 55 and ensuring that its targets are not rolled back is likely to be harder, not only because there will be a larger contingent of climate-sceptic ECR and ID MEPs, but also because the EPP is already tilting in the same direction, worried about losing support from angry voters. The EPP, for example, turned against the Nature Restoration Law earlier this year. Around a third of MEPs from the Renew centrist-liberal group also voted against the law. MEPs from other political families, in particular from the socialist group, may also turn against green policies if their voters become concerned about the negative effects of climate legislation.

A right-wing surge could also have significant consequences for the EU’s efforts to uphold the rule of law in member-states where it is under threat, and for the EP’s role as an advocate for civil liberties. In theory, there would continue to be a majority of centrist MEPs, but a strong showing by right-wing parties could prompt some MEPs and national governments to soften their stance on rule of law and civil liberties issues – notably when the target government is a political ally. That has been a problem for a decade, with the most notable example being that of the EPP protecting Viktor Orbán until that became untenable, but the situation could worsen. Matters will be even more complex if far-right leaders, like Kickl, end up at the European Council table, shaping decisions on whether to sanction member-states that breach EU values.

When it comes to migration, the impact of a stronger right-wing contingent in the EP may not change things much. Ever since 2015, the EU’s approach has been closely aligned with right-wing positions – even though for different reasons centrist politicians and right-wing ones had no interest in highlighting this. The EU’s overarching aim has been to reduce the number of people reaching its borders. The Union has also struck a range of agreements with third countries to take back individuals whose asylum applications had been rejected and to tighten control over their own borders so that fewer people would be able to reach Europe in the first place. The influence of the EP on these issues has been limited, as policies have been driven by the member-states and the Commission.

However, a bigger contingent of ECR and ID MEPs is likely to complicate the implementation of the recently agreed New Migration and Asylum Pact, which is meant to reform the EU’s migration system. The Pact’s rather limited provisions for intra-EU solidarity are particularly controversial with countries like Hungary and Poland, which have made clear they strongly oppose taking in migrants from other member-states. At the same time, the Pact imposes large new burdens on frontline member-states in terms of processing asylum applications more quickly. Countries like Italy may soon find they do not like the package they signed up to. All in all, that means EU migration policy is likely to remain focused on those few elements that member-states agree on: more closed borders and agreements with third countries.

When it comes to foreign policy, the EP election results are unlikely to undermine support for Ukraine or enlargement in the immediate term. While most members of ID are sceptical about supporting Ukraine, ECR members generally back additional assistance for Ukraine and EU enlargement. However, a strong showing by right-wing populist forces would have an indirect impact on EU enlargement. A right-wing surge is likely to put the brakes on the discussion of how to reform the EU’s institutions that will have to accompany enlargement. Some governments insist that the EU needs fundamental reform before enlargement. But it is difficult to see many countries being willing to give up their vetoes, for example on foreign policy, or agreeing to higher budget contributions, if they feel under pressure from right-wing parties at home, or if such parties are increasingly influential members of their own governments.

The EP election results are unlikely to undermine support for Ukraine or enlargement in the immediate term.

The EP elections results will also matter when it comes to the so-called European sovereignty agenda. This would entail member-states taking big steps in terms of deepening the single market, for example by moving towards a capital markets union. It would also require more EU-level investment, and necessitate larger EU-level budget resources (including perhaps a larger Union budget) to fund the green and digital transitions and greater defence investment. There are already formidable political barriers to progress on these issues, not least in the form of the current German government’s unwillingness to contemplate issuing joint debt. But a larger contingent of ECR and ID MEPs in the EP is unlikely to make such discussions any easier, given the emphasis that they place on preserving national sovereignty.

The EP elections in June will, in all likelihood, mark significant gains for right-wing populists and far-right parties. The impact is unlikely to be immediately evident, as centrist parties are set to maintain a majority of seats. Instead, their influence is likely to make itself felt over time, as mainstream political forces feel under pressure to tilt right on issues such as climate policy. More consequentially, the EP election results will also influence national politics, potentially giving more momentum to right-wing forces in upcoming elections and leading to changes in the balance of power within the European Council.

Luigi Scazzieri is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment