What to expect from the Digital Markets Act

Thanks to the Digital Markets Act, large tech firms must now give Europeans more choices about how online services work. But competition authorities will see few reasons to relax.

On 6 March, Europeans will see changes to large tech firms’ services. Google’s search results will give more prominence to its competitors’ offerings. Consumers will get more choices about how their data is handled. Apple’s closed ecosystem will become more open – allowing users to download apps without using Apple’s App Store. The reason for these changes is that Europe’s long-awaited Digital Markets Act (DMA) will start to bite. The law imposes rules on big firms’ platforms – including operating systems, online marketplaces, messaging services, social media networks, browsers, and digital advertising services – with the somewhat vague goal of making digital markets more ‘contestable’ and ‘fair’. However, the DMA’s elusive objectives make it hard to know whether the law will be a success. The DMA may help solve some problems with digital competition – but it leaves others unresolved and may even create new ones.

Despite the flaws in the Digital Markets Act, it is in large tech firms’ interests to make the law a success. If it fails, large tech firms will probably find themselves facing even tougher regulation.

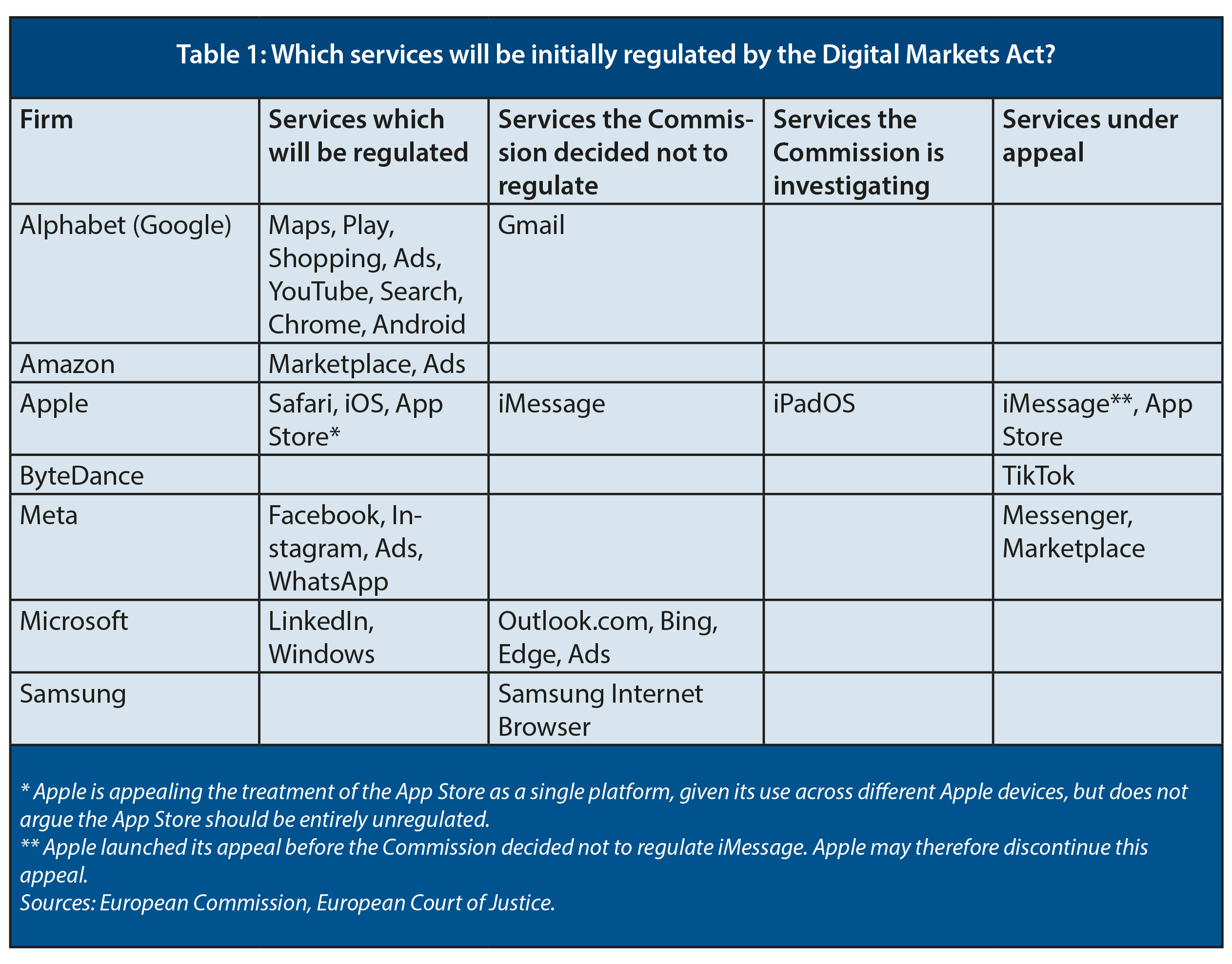

The DMA passed its first hurdle – allowing the Commission to quickly and efficiently decide which services to regulate – with a reasonable degree of success. As Table 1 shows, the largest tech firms mostly accept that their flagship services must follow the DMA’s rules. The Commission also quickly agreed with tech firms that some popular services did not warrant regulation. Some cases have proven more complex. The Commission is still investigating whether to regulate Apple’s iPad operating system, and should reach a decision in September 2024. On top of that, ByteDance (which runs the social media platform TikTok), Meta and Apple have all launched litigation in EU courts about whether their services should be regulated. Apple, for example, argues that its App Store should only be regulated when it distributes apps for iPhones, not for other Apple products. The Commission will also have to decide shortly whether some other services, like Booking.com’s online travel platform and the X (formerly Twitter) social network, should be regulated.

In the meantime, however, even firms which have appealed must comply with the DMA from 6 March, and have started announcing parts of their compliance plans. This exercise illustrates three key limitations of the DMA.

First, the impact on competition will be mixed. To its credit, the Commission has decided not to regulate some ‘challenger’ services, even when those services are provided by ‘big tech’ firms. These unregulated services include Apple’s iMessage, which has a smaller user base than WhatsApp, and Microsoft’s internet browser Edge and its search engine Bing, which are smaller challengers to Google Chrome and Google Search respectively. The Commission’s approach should enhance competition – it means some ‘challenger’ services will face fewer constraints, and could more easily become successful, increasing competitive pressure on the most dominant services. While this sounds sensible, the Commission’s approach is in fact bold because the DMA is not supposed to be a branch of competition law – it uses a new set of concepts that is supposed to regulate firms based solely on factors like their size and importance for business users, not whether or not they are ‘dominant’ or a ‘challenger’. The Commission’s approach may disappoint smaller browsers and search engines, who want more visibility, or stakeholders who understandably feel that the DMA was supposed to force all large technology firms to obey the same rules. But if Microsoft was forced to offer users a choice, almost all would choose Google products, helping the biggest products grow even bigger and making it even harder for Google’s biggest challenger to build scale.

The Commission has taken bold decisions not to use the Digital Markets Act to regulate ‘challenger’ services like Microsoft Bing and Edge – illustrating the enduring influence of competition law.

The DMA’s design, however, means that the Commission was not able to achieve such a sensible result in every case. For example, Apple will have to offer a browser choice screen on iPhones. The browser choice screen will probably encourage iPhone users to stop using Apple’s default browser Safari in favour of the better-known Google Chrome – a product which already has the largest market share in Europe.

The rules the DMA requires regulated firms to follow will also have ambiguous impacts on competition. Regulated firms must now ask users to make many more decisions – for example, about how their data is used, which apps and search engines are defaults, whether to buy products and services without using large tech firms’ platforms, and whether they want their usage of different services to be linked. More choice will enhance competition – especially where consumers currently do not have a realistic choice at all, such as iPhone users who have no choice but to use Apple’s App Store to download an app. However, there is a risk that many consumers will not exercise those choices. In some cases – such as when consumers are asked how their data can be used – many everyday consumers might not understand what they are being asked. In other cases, they will succumb to the same ‘choice fatigue’ that plagues Europeans when they face endless cookie requests online. Consumers who do understand their choices will realise that, in at least some cases, choices may have negative consequences – for example, unlinking Facebook and Instagram means the two services may not interact as seamlessly. This may help explain why Meta and Google seem relatively relaxed about complying with the DMA.

Second, implementation will be heavily disputed. Law-makers tried to make the DMA ‘self-executing’ – by setting black-and-white rules that give large firms little discretion about how to comply, and by setting very large potential fines to deter non-compliance. But implementing the rules poses significant challenges in practice. Take, for example, the rule that Apple must allow competing app stores, so that users are not forced to use the Apple App Store to download apps. This is one area where the DMA could create more choice and competition – with some clear benefits to consumers, such as lower prices for apps. Apple has announced – with obvious reluctance – its plans to comply with the DMA. But Apple will impose a range of limitations and conditions, such as a new set of fees for developers who want to take advantage of their rights under the DMA and a range of security measures that may persuade many developers to stick with Apple App Store. Many of the security measures seem broadly reasonable and law-makers were right to allow Apple to protect users’ security. But the devil will be in the details. Apple has mixed incentives: it legitimately wants to protect users’ security from malicious apps, but it may also be tempted to make life harder for developers that want to use alternatives to its App Store. Authorities will need to supervise Apple closely to ensure that its rules are designed and applied fairly and in the spirit of the DMA.

Apple’s strategy poses a challenge for the EU’s Digital Markets Act. The law will not be able to quickly resolve many detailed technical and pricing disputes about Apple’s plans.

The DMA does not offer any simple way for the Commission to resolve many disputes quickly or to address detailed economic questions about what a ‘fair’ level of fees would be. The Commission can ‘specify’ how firms must comply with most of the rules. However, that process will take months and regulated firms will probably litigate if they are unhappy with the result. That means it may take years for all the disputed details to be ironed out – and until then, many developers will probably shy away from exercising their rights under the DMA. So even where the DMA will have positive outcomes, they will take time to appear.

Third, competition authorities will not stop scrutinising tech firms. The DMA’s relationship with competition law is complex. In some cases – like Spotify’s complaint that Apple gives its own music service unfair advantages – the Commission has taken a long time to progress investigations. For example, it has just fined Apple €1.8 billion, two days before the DMA will force it to change its behaviour anyway. In other cases, large tech firms may have been influenced by the DMA to settle their disagreements with the Commission, on the basis that the DMA will force them to change their conduct, even if the Commission’s competition law investigations do not. Amazon, for example, has promised to limit its use of data about other businesses which sell on its marketplace, and to adjust which sellers have the most prominent placement in search listings. These commitments will go a long way to securing Amazon’s compliance with the DMA.

But the DMA leaves many more competition issues unaddressed – and could even create new ones. For example:

- The DMA is unlikely to solve problems with digital advertising, which form the bulk of Google’s and Facebook’s profits. Google has come under scrutiny in recent years because it dominates multiple parts of the digital advertising value chain – it helps online publishers manage their advertising space, helps advertisers manage their ad placements, and also operates exchanges which purport to give both publishers and advertisers the best price. Competition authorities believe this creates conflicts of interest. The Commission (alongside US antitrust authorities) believes the only tenable solution is for Google to sell parts of its ad business – an outcome the DMA is unlikely to ever require.

- The European Commission and member-state competition authorities are increasingly looking into cloud computing, a market dominated by Amazon, Microsoft and Google. Businesses complain that they find it difficult to switch cloud computing providers. And cloud computing is an essential input into artificial intelligence services, a market where competition authorities want to ensure there is a diverse range of independent providers. Cloud computing is in the DMA’s scope – but, for reasons the Commission has not explained, no cloud computing services will be regulated initially. Instead, the EU has pushed ahead with other laws like the Data Act to address problems in the cloud market, and competition authorities are carefully scrutinising both cloud and artificial intelligence services under traditional antitrust laws.

The DMA even risks creating new disputes. For example, it requires Apple to give all browsers on iOS the same functionality that is available to Apple’s own browser, Safari. Apple considered that it was “not practical” to extend all functionalities to other web browsers while maintaining its existing security standards. It therefore proposed to remove the ability for app developers to make webpages that use Safari but function like standalone apps. This would have removed a key way app developers can avoid Apple’s App Store today, albeit one that was little used in practice. Apple backed down after the Commission started an informal investigation into this conduct – but the dispute was a sharp reminder that large firms may purport to comply with the DMA in ways that the Commission dislikes.

These issues illustrate that the DMA will not put an end to the European Commission’s increasing scrutiny of large technology firms’ practices in Europe.

Despite these challenges – many caused by the DMA’s own flaws – it is in large tech firms’ interest to make the DMA a success. For one thing, law-makers have already raised the prospect of amending the DMA to expand its scope to cover new services like artificial intelligence, to regulate cloud computing, and to address unintended consequences. If tech firms work to resolve these concerns constructively, that may dissuade law-makers from reopening the DMA. Second, many other countries are proposing their own laws to improve digital competition. If those countries look to the DMA for inspiration, that would be a relatively good outcome for large technology firms. Imperfect as it is, the DMA has a clearly defined scope and a predictable set of requirements – and firms will find it easier and simpler to comply with a single set of rules globally.

European competition authorities will have little reason to leave big tech alone, despite the Digital Markets Act.

If the DMA does not deliver quick and positive results, and especially if large firms look recalcitrant, other countries are likely to decide that their own digital competition laws must be tougher than the DMA. They will then pursue laws that give regulators more discretion, provide less accountability and predictability, and risk forcing firms to comply with different rules in different countries. Resisting the DMA is unlikely to be a good long-term strategy.

Zach Meyers is assistant director of the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment