Is the Spitzenkandidat process a waste of time?

The Spitzenkandidat (lead candidate) process has not fulfilled its promise of engaging the average voter. Still, it has helped ‘europeanise’ the European Parliament elections and is worth persisting with.

Who should decide who becomes the President of the European Commission, the EU’s executive body? One option is the (democratically-elected) governments of the member-states. Another is the (democratically-elected) European Parliament. The Spitzenkandidat (lead candidate) process is a compromise that was supposed to give both intergovernmentalists and federalists some of what they wanted. This insight explains both why it has not worked as intended so far, and also why the European Parliament nevertheless should double down on it for the 2029 elections.

The origins of the process

The Spitzenkandidat process does not appear in any treaty, though it reflects the evolving role of the European Parliament in the appointment of the European Commission, and the changing balance of power between national governments and MEPs. The Treaty of Rome gave the Assembly (the European Parliament’s predecessor) no role in appointing the Commission or its president: both were appointed by consensus of the Council. The Maastricht treaty of 1992 obliged the Council to consult the Parliament before nominating the Commission president; the Parliament then had to approve (or reject) the Commission as a whole. In the Amsterdam treaty of 1997, the Parliament for the first time gained the power to approve the Commission president separately from the rest of the Commission.

It was the 2009 Lisbon Treaty that (implicitly) created the basis for the Spitzenkandidat process: Article 17 of the Treaty on European Union now states:

“Taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for President of the Commission. This candidate shall be elected by the European Parliament by a majority of its component members.”

The phrase “taking into account the elections” was not intended to mean that the European Council should cede the right to choose the Commission president to the largest party group in the Parliament, but the Parliament saw an opening to tilt the balance of power in the EU in its favour, and to make the Commission president more dependent on the favour of MEPs than national leaders. MEPs wanted each European political party to nominate a (lead) candidate for Commission president before the elections. After the elections, the European Council was supposed to endorse the candidate from the party that won the most seats. The European Parliament would then approve the appointment. Proponents of the process argued that it would get rid of the opaque horse trading in the European Council that accompanied the selection of Commission presidents. By giving European voters the opportunity to directly influence the selection of the Commission president, supporters also argued that the process would increase the EU’s democratic legitimacy. Finally, many hoped that more personalised campaigns would increase voter turnout and citizen engagement.

Success in 2014, failure in 2019

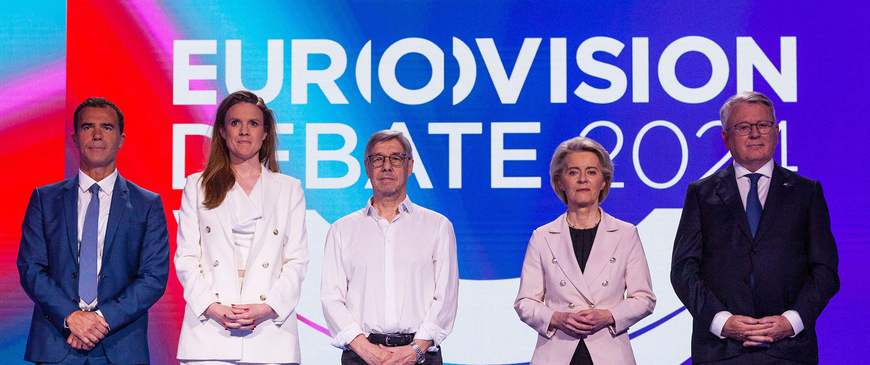

Ahead of the 2014 elections, five European political parties nominated lead candidates. The lead candidates visited different EU member-states and took part in televised debates that were broadcast in several languages and by different media outlets. Proponents of the lead candidate process welcomed this as a step towards a truly European public sphere. As in previous elections, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) emerged with the most MEPs; its Spitzenkandidat was the former prime minister of Luxembourg Jean-Claude Juncker.

The European Council had been critical of the lead candidate process and viewed it as an attempt to subvert its power in selecting the Commission president. There was resistance from several members of the European Council to Juncker’s appointment, including from the UK under its then-prime minister David Cameron. But there was remarkable cohesion within the European Parliament in support of Juncker, which came as somewhat of a surprise to the European Council, and he was eventually approved by both the European Council and the Parliament as Commission president.

After the experience of 2014, the Parliament tried to institutionalise the lead candidate process. Then-European Council President Donald Tusk, however, while not categorically rejecting the process, insisted that the largest party’s nominee would not automatically be put forward for Commission president by member-states after the next elections, stressing the autonomous competence of the Council in the nomination of a Commission president candidate. Within the EPP, Angela Merkel (then-chancellor of Germany) and Herman van Rompuy (former prime minister of Belgium and former European Council president) opposed the process. Nevertheless, the EPP eventually put forward a lead candidate for the 2019 election: Manfred Weber, the leader of the EPP group in the Parliament.

Even though the EPP once again won the largest number of seats, the European Council refused to nominate Weber as Commission president. There was opposition to the lead candidate process generally and to Weber as a candidate. Heads of state and government, such as French president Macron, had serious doubts about his lack of executive experience – a contrast with Juncker, who, as a former prime minister, was generally seen as well qualified. Frans Timmermans, the lead candidate put forward by the Socialists, also faced opposition in the European Council. Instead, the Council nominated Ursula von der Leyen, a German CDU (and therefore EPP) politician and former defence minister, who had not been associated with the lead candidate process in any way. She managed to secure a majority in the European Parliament and was elected Commission President.

The 2024 European Parliament election campaign

The 2019 experience led analysts and journalists to proclaim the death of the Spitzenkandidat process. Despite this, several European political parties once again put forward contenders to be Commission president ahead of the 2024 elections.

The party elites themselves seem uncertain about the Spitzenkandidat process, however. The EPP supports von der Leyen, who is fighting for a second term as chief of the Commission. But apart from her – well-known as the incumbent president – the average voter would be hard-pressed to name any of the candidates. The Party of European Socialists (PES) has put forward Nicolas Schmit from Luxembourg, the current Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights. He might be a well-known name in Luxembourg; in other countries he is not. He is a comfortable candidate behind whom the socialist parties can unite in an uncontroversial campaign, but he does not seem serious about becoming the next Commission president. If the goal of PES were actually to replace von der Leyen, they would have selected a candidate with more star power, for example former Finnish prime minister Sanna Marin.

The EPP supports von der Leyen, who is fighting for a second term as chief of the Commission. But apart from her – well-known as the incumbent president – the average voter would be hard-pressed to name any of the candidates.

Both Liberals and Greens have put forward multiple lead candidates, which likewise shows that they see their lead candidates not as realistic contenders for the Commission presidency, but rather as figures who can unite their party families. The Liberals have three lead candidates: Valérie Hayer and Sandro Gozi from France and Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann from Germany. Each of them represents one of the factions that form the ‘Renew Europe’ political group in the Parliament. This is actually an improvement on 2019, when the Liberals put forward seven candidates as a joint ‘Team Europe’. Strack-Zimmermann is a fixture on German talk shows but has never before appeared on the European stage. The European Green Party (EGP) has put forward a duo of Terry Reintke from Germany and Bas Eickhout from the Netherlands.

Groups on the populist right have not engaged with the process at all. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) did not nominate a lead candidate, amid disagreements on whom to support as well as doubts over the process in general. The Identity and Democracy Party (ID) likewise did not field an official lead candidate due to ideological opposition to the process.

While the lead candidates have been touring Europe and going head-to-head in political debates for the last few weeks, the Spitzenkandidat process is only partially achieving its original goals. The lead candidate process was supposed to clarify the link between the European Parliament elections and the new Commission president for voters across Europe. It was also supposed to do away with horse-trading in the European Council, but events in 2019 showed that it failed on both accounts. Von der Leyen has a good chance of becoming Commission president again, but her success will depend more on the support she can muster from the European Council and a variety of political parties from centre-left to populist right in the European Parliament than on the fact that she is the EPP’s lead candidate.

Towards transnational lists

Despite its shortcomings, however, the lead candidate process has some benefits. It contributes to making the European Parliament elections a more European undertaking by bringing European political party families closer together. They are forced to put forward at least some semblance of a coherent European message through a common candidate, more effectively than through their publication of a common manifesto (which no one reads).

The Spitzenkandidat process has brought European political families one step closer to becoming fully fledged parties with all the associated responsibilities, for example, nominating candidates for public office. But to ensure that one of the lead candidates ends up as Commission president, European political parties need to put forward high-profile candidates. Lead candidates that are not former heads of states or governments, or ministers are unlikely to be taken seriously by the European Council. Additionally, if the lead candidates were all people with the requisite profile, skills, and government experience needed for the job, the European Parliament could use its power to reject any nominee as Commission president who was not a lead candidate with confidence that the job would be filled by someone capable.

But to ensure that one of the lead candidates ends up as Commission president, European political parties need to put forward high-profile candidates.

One reform proposal would enable the Spitzenkandidat process to fulfil its purpose and ‘europeanise’ the European election campaign not just for party elites but also the average voter: the lead candidates should run on transnational lists. In the current system, national parties put forward the lists of candidates for the European Parliament elections. This means that citizens can only vote for candidates in their own country of residence (or citizenship, if the two differ). Proponents of transnational lists argue that there also should also be an EU-wide constituency. Voters should have two votes, one for a candidate in their national ‘constituency’, and one for a candidate in an EU-wide constituency.

Transnational lists are not a new idea. The European Parliament has long backed the formation of such lists in order to create a European constituency. While there was some hope from proponents of transnational lists that the European Parliament seats lost due to Brexit could be used for this purpose, transnational lists will not be a reality in the 2024 elections due to rejections from the Council.

If the lead candidates were transnational candidates, however, they would be forced to campaign in a way that engages all EU citizens. Their faces, for example, would be showcased on billboards across Europe (which is currently not the case), and they would have to address their campaigns towards all Europeans rather than only those in their national constituencies. Then the lead candidate process would accomplish its original purpose of connecting the European Parliament election and the Commission presidency more visibly for citizens. It would also be a small step on the road to changing the political narrative and encouraging Europeans to think of themselves more as EU citizens instead of solely citizens of their home country.

If the lead candidates were transnational candidates, however, they would be forced to campaign in a way that engages all EU citizens.

Currently, the future of the lead candidate process is uncertain. It is not enshrined in any EU treaty or law. Should governments decide after the European Parliament election that they do not wish to see any of the lead candidates as Commission President (as in 2019), they could permanently kill off the idea. While the lead candidate process in its current form is far from perfect, this would be a step backwards.

For now, it seems likely that the current EPP lead candidate, von der Leyen, will secure another mandate at the head of the Commission. If that happens, the next European Parliament should focus its efforts on institutionalising the process, working towards transnational lists and credible Spitzenkandidaten for the 2029 European Parliament elections. That would probably set off an inter-institutional battle with the European Council; but if the outcome were European voters who felt more committed to the European project, and better candidates for Commission president, that would be a fight worth having.

Christina Keßler is the Clara Marina O’Donnell fellow (2023-24).

Add new comment