President Biden: Don't expect miracles, Europe

Transatlantic relations will improve under Biden, but Europe will not be his number one priority. Europeans must strengthen their capacity to protect their own interests.

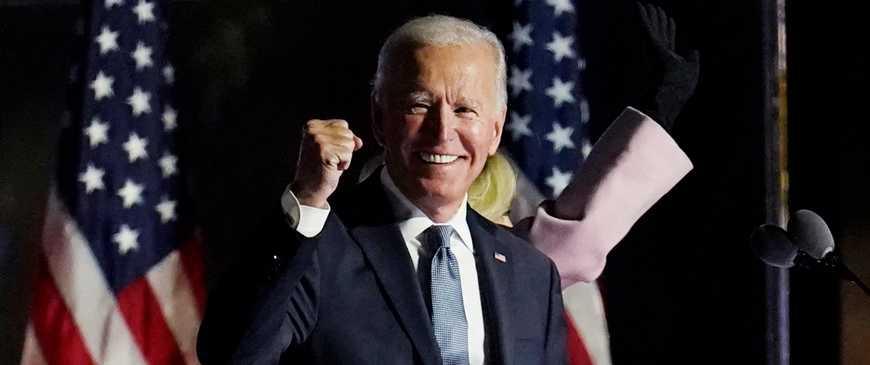

Joe Biden’s election as US president will make it easier for the EU and the US to forge a common transatlantic approach to many of the challenges facing them. European leaders greeted the news of Joe Biden’s victory over Donald Trump with enthusiasm, with High Representative Josep Borrell welcoming “the chance to work once again with a US president who doesn’t consider us a ‘foe’”.

Borrell’s comment encapsulates the main change Biden will bring: unlike Trump, Biden will not try to undermine the EU or NATO. He believes that international institutions and multilateral co-operation serve US interests. And whereas Trump sought to divide the EU by supporting authoritarian populist leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Biden will back more mainstream pro-EU leaders. European populists will no longer be able to look to the US president for legitimation of their actions. That will undermine their political influence in the EU. But the populists will not disappear: their support is largely driven by perceived economic injustices and cultural conflicts within European societies, rather than by international politics.

Biden will not try to undermine the EU or NATO: he believes that international institutions and multilateral co-operation serve US interests.

Under Biden, transatlantic trade tensions will lessen and some of the tariffs imposed by both Trump and the EU are likely to be removed. There is also a good chance that the long-standing dispute over subsidies to Boeing and Airbus will be resolved. But Biden is unlikely to make further trade liberalisation with Europe a priority. Neither Democrats nor Republicans are currently great champions of free trade. Biden’s rhetoric has been quite protectionist, with ‘Buy American’ provisions prominent in his campaign. Moreover, many European voters were opposed to the never-concluded Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) under negotiation during Obama’s presidency. The EU will also need to decide whether it wants to risk tensions with Biden’s administration by fining US digital companies for infringing competition rules, or by pushing ahead with plans to impose special taxes on digital businesses.

In the field of security and defence, Biden is a firm believer in the value of alliances. He will recommit the US to NATO and to the defence of its allies, strengthening deterrence, and may also rethink some of Trump’s troop withdrawals from Europe. Transatlantic defence debates will become more civil, with Europeans no longer treated as if they owe money to the US. But underlying tensions over burden-sharing will persist. The US will still press Europeans to meet their NATO commitment to spend 2 per cent of GDP on defence. While this seems challenging, given the economic pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic, European countries should maintain current levels of defence spending. Washington will also continue to lobby member-states to ensure that EU defence initiatives such as the European Defence Fund allow US firms to maintain their position in the European defence market. Member-states should be open to defence industrial co-operation with the US, where there is a clear benefit to European security.

Europe and the US are likely to re-establish co-operation on combating the COVID-19 pandemic quickly. Biden has pledged to rejoin the World Health Organisation (WHO), from which Trump had withdrawn. On climate policy too, there is likely to be scope for the EU and the US to work together closely, as Biden will re-join the Paris climate agreement, which Trump had also left. His ability to invest in green priorities and launch a Green New Deal will be constrained, however, if (as seems likely) the Democrats lack a majority in the Senate. But the EU and the US should try to co-operate on other areas, for example co-ordinating assistance to developing countries to reduce emissions.

Biden is a firm believer in the value of alliances. He will recommit the US to NATO and to the defence of its allies, strengthening deterrence.

Biden’s administration will be much more willing to consult and co-ordinate on foreign policy with the EU, and to find common approaches to a range of issues. Re-establishing a common transatlantic approach to Iran should be relatively straightforward. Biden has stated his intention to rejoin the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – the nuclear deal that Trump withdrew from – on condition that Iran returns to full compliance. This will not be easy, as Iran has very little trust in the US, does not want to make unilateral concessions and wants compensation for Trump’s sanctions. Europeans should facilitate contacts between the US and Iran and choreograph a return to the agreement, with Iran gradually rolling back its nuclear activities in exchange for the US allowing it to export more oil. This should ideally take place before Iran holds presidential elections in mid-2021, as they are likely to strengthen political forces in Iran that oppose making concessions and are sceptical of the deal.

EU and US policies towards Turkey will also become more aligned. Like the EU, Biden does not seek confrontation with Turkey and wants to keep it within the NATO family to prevent it from building closer links to Russia. But Biden is likely to be willing to apply pressure to Ankara to halt its aggressive maritime behaviour towards Greece and Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean and to dissuade it from deploying its Russian-made S-400 air defence system. The EU should seize the opportunity to forge a more co-ordinated transatlantic approach that can steer Ankara towards moderation.

On Israel-Palestine, Biden will be less pro-Israel than Trump, re-committing the US to the two-state solution and potentially enabling greater co-operation with the Europeans. However, he has said he will keep the US embassy in Jerusalem, and Europeans should not expect him to put great pressure on Israel to halt settlement construction in occupied territories, still less force it to implement a two-state solution.

Europeans should be prepared for the US to take a less prominent role in conflicts in Europe’s neighbourhood. Biden has promised to end ‘forever wars’, withdrawing most US troops from Afghanistan and reducing the US presence elsewhere in the Middle East. He will probably use US forces only to provide limited support to allies on the ground, and will make extensive use of drones and special forces to counter terrorism across the MENA region and in the Sahel. Europeans cannot count on the US to advance their interests. They will have to co-ordinate their own positions and take the lead in proposing joint policies to address regional conflicts like those in Libya or Syria. More broadly, Biden will be under domestic pressure to prioritise human rights concerns in US relationships with allies like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. This could lead to a divergence with Europe, which tends to pay little attention to upholding human rights in the Middle East and North Africa because it depends on its partners there to control migration and fight terrorism.

Biden played a leading role in the Obama administration’s handling of Russia, Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans and is likely to take a continuing interest in the region. He will be more willing than Trump to engage in arms control with Russia: an early task will be to extend the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty, which is due to expire on February 5th 2021. But on other issues Biden is likely to take a firmer line: he is a long-standing backer of NATO membership for Georgia, Ukraine and countries in the Western Balkans, and a strong critic of Vladimir Putin. Europe may be disappointed if it is hoping for a softer US line on one of the most contentious issues in EU-US relations: Biden is unlikely to block Congressional action to impose sanctions on European companies involved in building the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany.

The most important foreign policy issue in Biden’s in-tray will be America’s relationship with China. It will be challenging to establish a fully coherent joint transatlantic approach. There is bipartisan American concern about China’s rise and its assertive foreign policy; European countries are more divided in their views on China. Biden will adopt a less abrasive tone towards Beijing, and will seek China’s co-operation in areas of mutual interest, but the substance of US policy on China will remain tough. Biden will continue to push allies not to use Huawei equipment in their 5G networks. He will pay more attention than Trump to China’s human rights record, whether in Xinjiang or Hong Kong. It is even possible that the competition between the US and China may intensify. There is a group of Democrats that sees competition with Beijing as part of a broader struggle between democracy and authoritarianism, and thinks the US needs to adopt a much stronger stance towards China. Europe has become more concerned about the direction of Chinese domestic and foreign policy, but it has yet to formulate a comprehensive strategy for dealing with China. Europeans will inevitably be more closely aligned with the democratic US than authoritarian China, but they should resist being dragged into a broad US-China confrontation.

For the UK, Biden brings some good news and some bad. His election increases the chances of a successful COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow in November 2021. London will welcome his support for NATO. His multilateral approach to international problems will create opportunities for the UK and US to co-operate in bodies such as the WHO. But Biden and those around him have not hidden their opposition to Brexit and their belief that it makes the UK less relevant as a security partner for the US. And Biden, who is proud of his Irish heritage, has already made clear to Boris Johnson the importance he attaches to the Good Friday Agreement in the context of future UK-EU trade arrangements – a shot across the bows as the UK threatens to violate the Northern Ireland Protocol to the Withdrawal Agreement. Johnson will have to work hard to distance himself and his government from past ties to Trump and the right wing in the US.

Biden’s victory is unambiguously good news for Europeans. A second Trump term risked putting an end to the transatlantic partnership. Transatlantic tensions in many policy areas will decrease substantially, and Europe and the US will be able to re-establish a common approach towards many shared challenges. Relations might not be as rosy as most Europeans think, however: many disagreements preceded Trump, and will outlast him. Moreover, Biden is almost certain to be a one-term president and will overwhelmingly be focused on fighting COVID-19 and its consequences, and trying to heal America’s political divides, not on Europe’s problems. If the Democrats do not control the Senate (their only chance is to win both run-off elections for Senate seats in Georgia in January), Biden may be unable to pass the legislation he needs to deliver the transformational agenda that many of his voters and his European supporters expect on issues such as climate change.

Biden will not be able to reverse deep structural shifts in US politics and foreign policy.

Above all however, Biden will not be able to reverse deep structural shifts in US politics and foreign policy. Europeans should be mindful of just how popular Trump’s brand of politics is in the US, and should not see him as an aberration. At the height of a mismanaged pandemic, Trump gained votes compared to 2016, forging a diverse coalition and coming close to winning the election. A more polished version of Trump, with the same ideas, could easily have prevailed and might prevail in 2024. Europeans should also keep in mind that Biden’s past involvement with European issues will not change the fact that China’s rise is dragging the US’s focus away from Europe and its neighbourhood and towards the Pacific. Europeans should not be tempted to think that they have the luxury of being able to do nothing. They should invest in strengthening their own capacity to protect their interests, whoever sits in the White House.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy and Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment