Premature elections won't stabilise Libya

The push for elections in Libya risks deepening the country’s divisions. Europe should agree on a common position, and work towards a settlement acceptable to key Libyan and regional players.

Recent violence in Tripoli left dozens dead, shattering the illusion of relative stability in Libya’s capital, and casting the country in the spotlight once again. Recent fighting should put a brake on a French-backed plan to hold elections in December. Superficially, elections might appear tempting as a means of breaking the political deadlock in the country, but security conditions do not allow for a free and fair contest, and Libya’s key players have not committed themselves to upholding the results. Elections risk deepening the country’s divisions and precipitating an increase in violence. Instead of searching for quick fixes through elections, Europeans should focus on stabilising the country over the long term. This will require European countries to work together, not against each other.

The push for elections in #Libya risks deepening the country’s divisions. Europe should agree on a common position, and work towards a settlement acceptable to key Libyan and regional players.

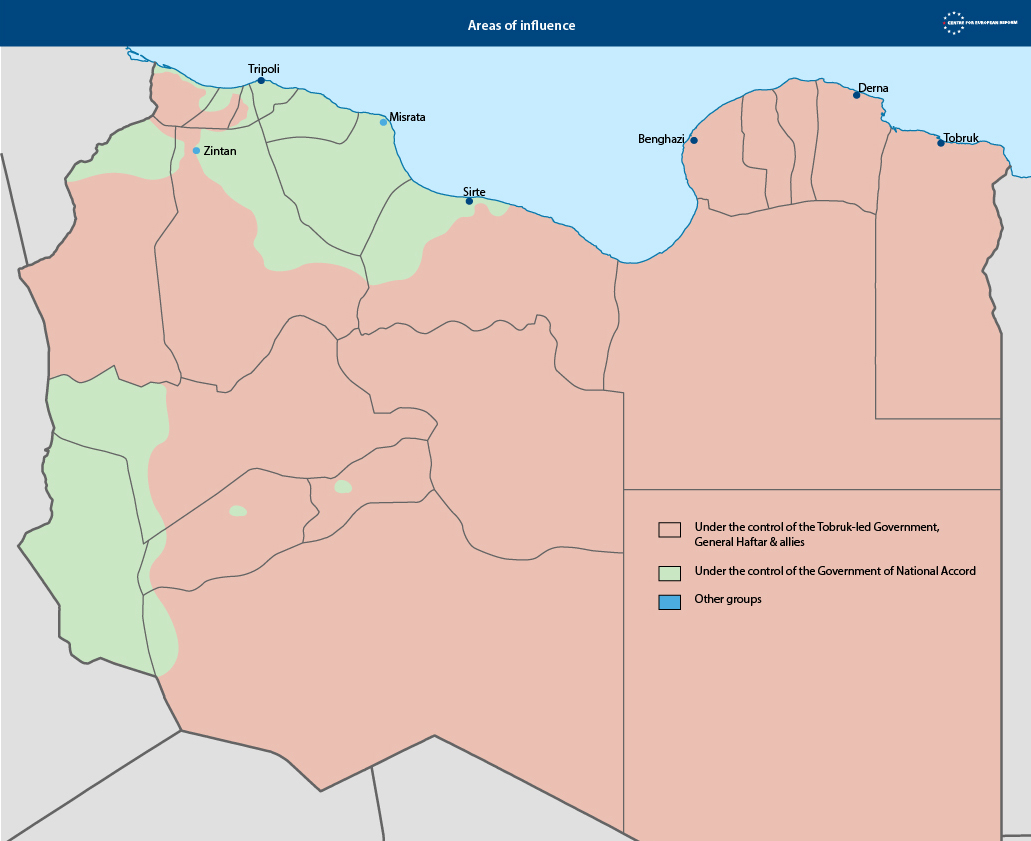

Since 2014, Libya has been divided between competing centres of power. In December 2015, the UN brokered an agreement, the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA), leading to the formation of a Government of National Accord, based in Tripoli. However, many Libyans never accepted the LPA. As a result, the Government of National Accord relies on the goodwill of militias, while its prime minister, Fayez al-Serraj, is a powerless figurehead. Libya’s parliament, the House of Representatives, is based in Libya’s east and has never fully endorsed the LPA. The House of Representatives has the backing of General Haftar, a strongman with close ties to Egypt and the UAE, and warm relations with Russia and France. Although the Government of National Accord and the House of Representatives are not openly fighting, there have been clashes between militias loosely aligned with either side. Haftar’s stated ambition is to control the whole of Libya, but this idea is anathema to many backers of the Government of National Accord, who oppose him because of his anti-Islamist stance. The cities of Misrata and Zintan are powerful actors in their own right, only nominally aligned with the Government of National Accord. In addition to these main players, there are a number of militias and extremist groups that often fight each other.

The biggest success of the international mediation efforts has been to prevent Libya’s fragmentation. International powers accomplished this by treating Libya’s national oil company as the only legitimate supplier of oil, and insisting that all proceeds from sales flow to Libya’s central bank. UN-sponsored mediation has also led to local ceasefires. However, no broader political settlement is in sight. In the autumn of 2017, UN Special Representative Ghassan Salamé launched a new initiative aimed at reviving the December 2015 LPA and holding a ‘national conference’, designed to bring all stakeholders in Libya together and act as a stepping stone to fresh elections and a new constitution. However, the plan quickly stalled, and the momentum shifted towards a French initiative designed to achieve a grand bargain between Serraj and Haftar. At a summit in Paris in May 2018, Serraj and Haftar pledged to hold early elections by December 10th.

However, there are practical, legal and political hurdles to holding elections so soon:

- In practical terms, security conditions are very poor. As underscored by recent bouts of violence, the government cannot even guarantee security in Tripoli. Even if conditions were better, the contest could not be free and fair, especially in the east, where Haftar’s forces exercise a tight grip.

- In legal terms, elections also lack a firm constitutional basis: Libya currently has no legal framework defining the institutions that would be elected and their powers. Libya has a draft constitution, which would transform its current system into a more presidential one. But there is no chance of the constitution being finalised by the December deadline, and the House of Representatives still has to approve the electoral law.

- Politically, the elections face strong headwinds. There are no signs that Libya’s key stakeholders intend to uphold their legitimacy or respect their results. The participants in the Paris summit endorsed but did not sign an eight-point agreement, and they began to disown the proposed elections as soon as they had returned to Libya. Haftar sought to consolidate his hold over eastern Libya by attacking the city of Derna and attempting to tighten his hold over key oilfields.

If they are held now, elections will not stabilise Libya, but deepen its existing divisions. They are unlikely to lead to consensus, but instead to winner-takes-all politics. Those parties who fear losing power will contest the result, and probably reject it. Even pushing for elections has led to instability, prompting militias in Tripoli to jostle for pre-electoral advantage.

Any effort to stabilise Libya needs to avoid past mistakes. The December 2015 LPA excluded powerful constituencies and had limited political buy-in even from its backers. The LPA rests on a narrow base because it treated Serraj and the Government of National Accord as representatives of western Libya as a whole. The UN and others pressurised the Libyans to agree the LPA quickly in 2015, without taking account of the views of important factions from other western towns such as Misrata and Zintan. Additionally, Haftar did not take the deal seriously, and continued to press for control of the whole of Libya. Any future agreement needs to be based on a more inclusive negotiating process, and to have a firmer basis.

European divisions in dealing with Libya has undermined the common European interest in a stable Libya. If Europe wants to have influence in shaping Libya’s future, Italy and France must find a way to better co-ordinate their policies.

However, there are few incentives for Libyan factions to engage seriously in reconciliation efforts, as the status quo appears sustainable and, for many, profitable. Militias compete for influence in Tripoli in order to control key government posts and access revenues from oil sales. This generates bouts of violence when those left out seek redress. It may be possible to stabilise Tripoli, as the recent UN backed ceasefire shows. But the more powerful actors are either unable or unwilling to compromise. Serraj is open to compromise, but is unable to deliver as he has very limited authority over militias in western Libya. For his part, Haftar appears willing to be involved in international talks only to the extent that it consolidates his authority.

The unwillingness of the different Libyan parties to compromise is compounded by competition between external powers. This makes it difficult to sanction spoilers or provide security through a UN peacekeeping mission. As a result, Libyan factions are only under limited pressure to agree to reconciliation or elections. While external powers are in theory supportive of UN efforts and back the Government of National Accord, in practice they support different sides. Haftar and the House of Representatives have received extensive support from Egypt and the UAE, and have close ties to Russia and France. Their support removes incentives for Haftar to compromise. Turkey and Qatar have provided support to militias in western Libya. Meanwhile, under the Trump administration, the US has taken a backseat in the political process, largely concerning itself with counter-terrorism efforts.

For its part, the EU has been disunited. Behind a veneer of unified statements and conclusions, Italy and France have clashed, especially since Emmanuel Macron became President. France has supported Haftar, seeing him as a source of stability and a bulwark against terrorism. In contrast, Italy’s economic interests and its efforts to stem migration have led it to develop close ties to western Libya, the most populous area of the country and geographically the closest to Italy. Rome, one of the main backers of the Government of National Accord, has extensively co-operated with militias to stem migration, and has close relations with Misrata. Italy, the only Western country that has kept its embassy in Tripoli open, has blamed France for destabilising Libya in search of prestige and commercial advantage, and sees Macron’s push for elections as a strategy to legitimise Haftar. Italy fears that France’s efforts to strengthen Haftar risk destabilising western Libya. Tensions between Macron and Italy’s new eurosceptic government have made it more difficult for Paris and Rome to defuse their differences.

European disunity on Libya undermines the notion of a common European foreign policy. It also undermines the common European interest in a stable Libya. If Europe wants to have influence in shaping Libya’s future, Italy and France must find a way to co-ordinate their policies on Libya. Italy is planning an international conference on Libya in Sicily in mid-November, which could be a chance for Paris and Rome to set their differences aside. Both Italy and France accept that a settlement needs to be based on a bargain between Libya’s major players. But Paris is mistaken in focusing on Haftar and Serraj, and excluding other actors. The French approach risks strengthening Haftar and fuelling a violent reaction. A settlement should aim to hold Libya’s factions in a state of relative equilibrium. On its part, Rome has now accepted that Haftar will remain an important actor in Libya, and that he cannot be excluded. However, it needs to give up on any illusion that it can stabilise Libya alone, as its resources are too limited.

Attempts to stabilise Libya have been undermined by divisions and competition between external powers. Together, European countries could push the various relevant parties towards such a compromise solution. But this requires them to agree with each other first.

If the EU manages to find a truly common voice, it could then push other parties towards a settlement that prevents further violence. It is not realistic at this stage to think of unifying Libya’s existing institutions or crafting a common military command structure. This would create winners and losers, which would lead to further conflict. Even in a best-case scenario, then, for the near future Libya will remain fragmented, with a weak central government. In the medium term, Europe should seek to promote a slow process of national reconciliation, and foster Libya’s economic recovery to improve citizens’ everyday lives. To this end, the EU should provide Libyan municipalities with economic assistance to stabilise the country at local level, and encourage dialogue between non-state actors such as civil society groups and municipalities. Politically, the EU should support the plan of UN Deputy Special Representative to Libya, Stephanie Williams, for a broad national conference, designed to bring together Libya’s key political actors. This has the potential over time to build a broader consensus on Libya’s future governance.

As long as external powers continue to back different factions, Libya will continue to be unstable. For Libyans to have a chance to craft a political settlement, all external actors need to coalesce first around a common position. Together, European countries could push the various relevant parties towards such a compromise solution. But this requires them to agree with each other first and avoid solutions that unilaterally seek to advance their interests.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment