Hungary, Poland and the EU: It's the money, stupid?

After years playing by the legal book, the EU is now using its purse strings to curb democratic backsliding in Poland and Hungary. This is a good tactic, but not a sustainable strategy in the long-term.

On December 12th 2022, the EU froze €6.3 billion of cohesion funds that were due to Hungary. The decision came after months of back-and-forth negotiations between the European Commission, which favoured a higher penalty; the Council of Ministers, which was wary of the political and economic consequences of such freeze; and the Hungarian government, which insisted the whole thing was a calculated smear campaign against Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In truth, Orbán had been irritating partners by holding up EU decisions on sanctions, energy and military support to Ukraine. But his refusal to back an €18 billion aid package to Ukraine at the beginning of December proved a step too far.

For the past three years, Warsaw and Budapest have managed to wield their veto power to extract concessions from Brussels in their long-standing dispute over the rule of law. In 2020, Hungary and Poland successfully managed to postpone the introduction of the EU’s rule of law conditionality mechanism in exchange for backing the bloc’s post-pandemic recovery fund. Last year, Poland threatened to block parts of the EU’s landmark ‘Fit for 55’ climate package unless Brussels green-lighted Warsaw’s plan for spending money from that fund. In December, Poland also briefly prevented aid to Ukraine, as it opposed a much-awaited plan for a minimum EU corporate tax rate which was part of the same negotiating package. And Budapest has been a constant thorn in the EU’s side as it tries to agree on a common response to Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

The EU’s strategy to deal with democratic backsliding in Poland and Hungary has been one of caution. The European Commission has repeatedly taken both countries to court for failing to comply with EU law. The Commission has also initiated so-called Article 7 disciplinary proceedings against Poland for breaches of the rule of law. The European Parliament has instigated a similar proceeding against Hungary and recently passed a resolution branding the country as an ‘electoral autocracy’. None of this has worked: Poland and Hungary disregard court decisions or re-litigate them endlessly; and they have supported each other in staving off their respective Article 7 procedures – which, if successful, would see Warsaw and Budapest losing their voting rights in the Council of Ministers but require unanimity to succeed.

Over time, the EU institutions realised that they could not solve Poland and Hungary’s rule of law problems by sheer legal and judicial force. They also learned that Fidesz and the ruling Polish coalition are less similar than they look at first sight. Orbán prides himself in being a disruptor, but his European policy is often erratic and lacks a long-term vision. Orbán´s relationship with Putin has been too close for comfort: in February 2022, he visited Putin in Moscow just three weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, at a time when tensions between the two countries were already high. For their part, Law and Justice leader Jarosław Kaczyński, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki and their junior coalition partner, Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro are wary of what they consider to be the EU’s liberal agenda and are pushing a national-conservative strategy to defend Poland from what they see as the Union’s encroachment on national matters. They are also staunchly anti-Putin.

Over time, the EU institutions realised that they could not solve Poland and Hungary’s rule of law problems by sheer legal and judicial force.

The main thing Orbán and the Polish government have in common is that they both depend heavily on EU money. Orbán´s autocratic grip on Hungary hinges largely on his ability to use EU funds to perpetuate his power. Law and Justice needs cash to finance its ‘Polish Deal’, a massive hand-out of tax reductions and benefits that Morawiecki hopes will help him win re-election in the autumn.

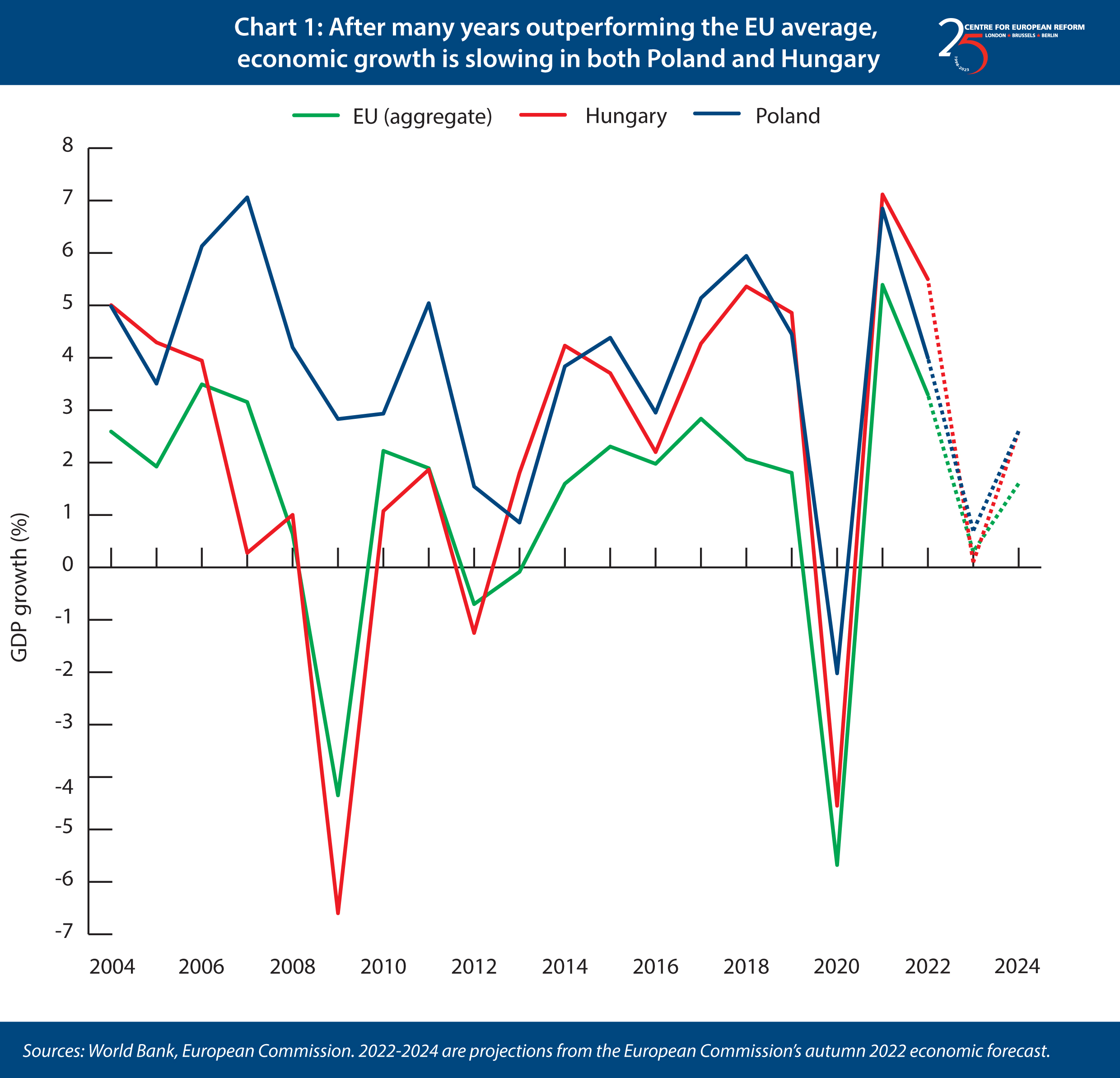

Neither Orbán nor the ruling Polish coalition can afford to lose EU monies right now. Hungary’s growth is stagnating, and a recession looms (see Chart 1). Inflation recently topped 24 per cent, the highest rate in the EU, as the government phased-out price caps that were creating shortages of fuel and other products. Hungary’s deteriorating economic situation, including a swelling current account deficit, has prompted investors to pull money out of the country, putting pressure on the currency and further fuelling inflation. The freezing of EU funds compromises both public finances – budget deficits are expected to clock in above 3 per cent for years to come – and economic growth: a staggering one-third of total public investment in Hungary comes from EU money, including 94 per cent of railways and 54 per cent of road investment.

In Poland, the immediate economic situation is less threatening: Warsaw has a lower public debt and a lower current account deficit. Still, growth has slowed down and a recession may be on the cards. Inflation runs at over 16 percent and government borrowing costs are growing.

Pressing this economic advantage, the Commission’s latest strategy to rein in Budapest and Warsaw has been shrewdly two-pronged: using EU funds as leverage, and exploiting the emerging cracks in both Orbán and Morawiecki’s bromance and in the Polish ruling coalition. So far, the plan has worked, at least on paper: Orbán has rushed anti-corruption reforms through parliament; and, on January 13th, the Polish Sejm passed a law undoing some of the judicial reforms that have been standing in the way of the disbursement of Poland’s recovery money. This law has pitted Law and Justice against Ziobro’s United Poland, which opposes it.

The EU may have won a battle, but it is far from winning the rule of law war. There are three reasons why the Union's latest strategy has worked. None of them is likely to stay constant over time.

First, the Commission was able to push ahead with freezing EU funds to Hungary despite pressure from the Council partly because Ursula von der Leyen is powerful enough to disregard the views of some member-states, particularly if she has the support of the European Parliament. The Parliament has been the most vocal critic of both Orbán and Morawiecki´s illiberal antics but its questionable management of its own corruption scandal threatens to erode the Parliament’s role as a rule-of-law champion. And von der Leyen’s hierarchical leadership style is sometimes counter-productive: in June, the Commission approved Poland’s recovery plan against the views of five commissioners. It was only when pressure mounted for von der Leyen to make sure that none of the money would actually be disbursed that Law and Justice got jittery and complied with a number of rule-of-law reforms.

Second, the war in Ukraine has exposed fractures in the friendship between Budapest and Warsaw that the EU was able to exploit. The war has also isolated Hungary, making it politically easier for both the Commission and the member-states to use the EU purse in their dealings with Orbán. But, while Poland may be irritated with Hungary’s tepid response to the invasion, the Polish government is still firmly on Orbán´s side when it comes to the rule of law. Morawiecki has given no indication that Poland will unblock disciplinary action against Budapest, because he does not want Orbán to retaliate by doing the same to Warsaw. And Poland did not want to use the conditionality mechanism against Budapest – the matter was eventually decided by qualified majority voting in the Council, because the conditionality mechanism, unlike Article 7 procedures, allows for it. As the war drags on, public support for Ukraine may begin to falter, in which case more countries in Europe may become more sympathetic to Orbán’s claims about sanctions hurting the European economy.

Most importantly, the Union has been able to use the carrot of its post-pandemic recovery fund to extract rule of law concessions from both Budapest and Warsaw. It is up to the Commission to assess whether member-states meet pre-agreed milestones and targets, including anti-corruption and accountability measures, and to greenlight money transfers. So the recovery fund gives the Commission more leverage than any of the other rule of law tools, which often require either the approval of the Council of Ministers or the unanimous agreement of all EU governments. But the recovery fund is not a rule of law mechanism by design, and, crucially, it is time-bound. On paper, the fund should run out by 2026. As EU funds are paid out and disappear into the rear-view mirror, the Commission’s leverage will unavoidably decrease. That means the wrangling over funds and vetoes could return, possibly every six months all the way to 2026, as milestones are assessed.

As EU funds are paid out and disappear into the rear-view mirror, the Commission’s leverage will unavoidably decrease.

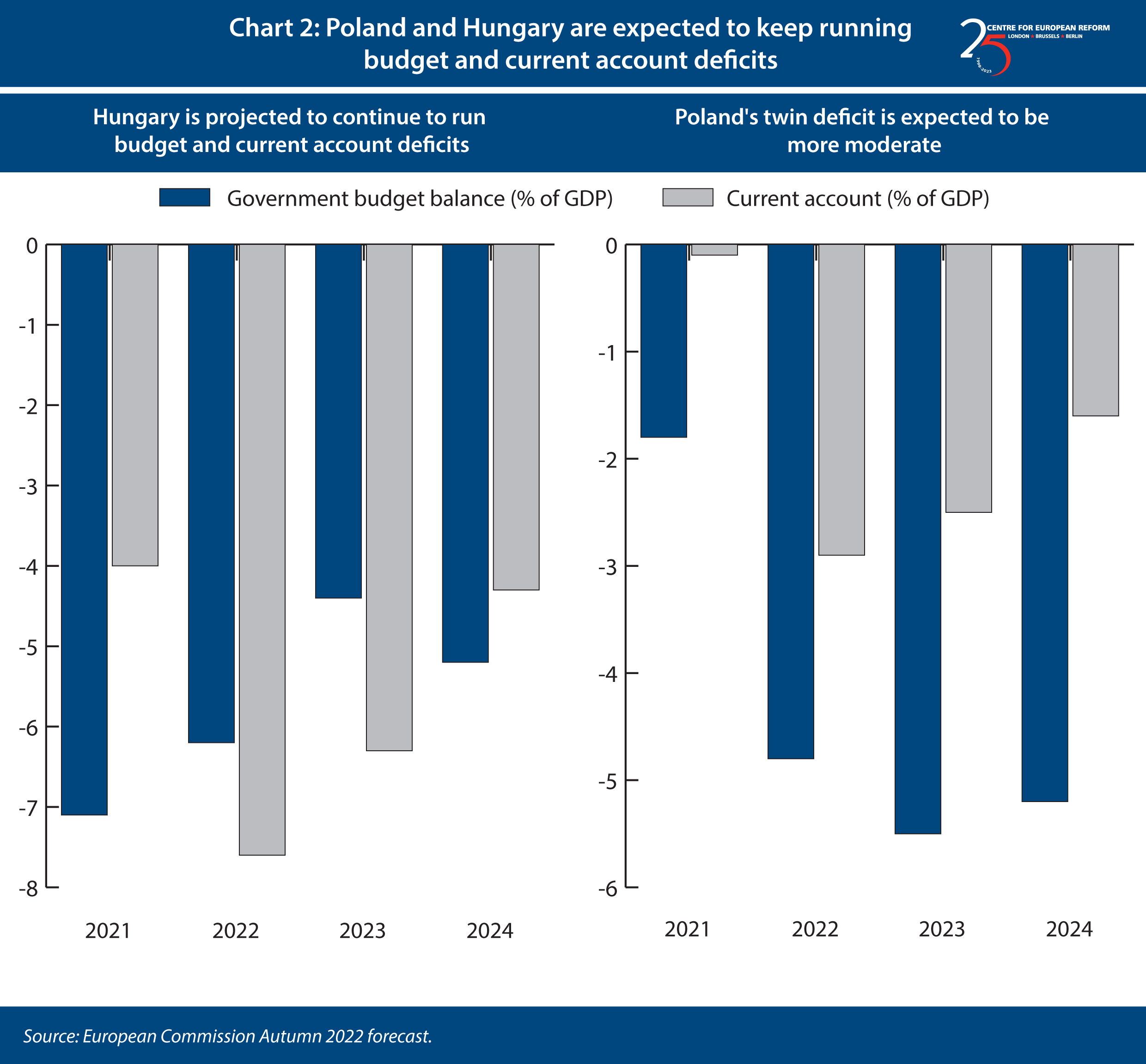

For now, the benefits of withholding EU funds outweigh the risks for Brussels. Neither Poland nor Hungary are eurozone members and their economies comprise only 4 and 1 per cent of the EU economy, respectively. The pair are also expected to keep running budget and trade deficits for the next few years and will continue to need the EU fiscal spigot. But, in the longer term, financial penalties alone will not solve the EU’s rule of law crisis and may end up backfiring if they trigger a full-blown economic crisis in either Hungary or Poland.

If EU funds are regularly frozen, investors will lose confidence and may stop financing Hungary and Poland’s budget and current account, or ‘twin’ deficits (see Chart 2). This would put much more downward pressure on their currencies and may ultimately lead to a balance-of-payments or financial crisis. Such a panic could spill over to other eastern-European countries and some pockets of the wider EU financial system that are vulnerable to instability in the region. For example, around 22 per cent of the Austrian banking system’s assets are exposed to central, eastern and south-eastern Europe.

In case of financial troubles in either Poland or Hungary, the European Central Bank may need to intervene to contain spill-overs or protect its balance sheet, especially if there are risks to the independence of Poland’s or Hungary’s central banks. Since the pandemic, the ECB has extended a swap line by which the Polish central bank can borrow up to €10 billion from the ECB in exchange for złoty. Through the swap, the Polish central bank could provide euro liquidity to stabilise banks if they struggle for funding in their own currency. Hungary, got a so-called ‘repo line’ of €4 billion, which, however, is less attractive than a swap because its central bank cannot borrow euros simply against its own currency but must provide euro-denominated assets to the ECB as insurance.

Hungary’s December deal with the EU narrowly avoided a sell-off by international financial markets that had grown increasingly jittery on Hungary. The forint exchange rate has since recovered ground vis-à-vis the euro while interest rates on Hungarian government bonds have decreased. The threat of a loss of financial market confidence in Poland has been much smaller but non-negligible. The market relief after the deal between Brussels and Budapest will not have been lost on Warsaw. The threat of an economic crisis is more useful for the EU than having one.

For the EU to defend the rule of law, the threat of an economic crisis in Hungary and Poland is much more useful than actually having one.

Vetoing decisions in exchange for concessions is a practice as old as the EU itself. So is using money to increase one’s leverage in EU decision making. But it is in nobody’s interest to resort to blackmail. If it wants to avoid constant disruption while ensuring that all countries comply with democratic standards, the Union should invest in a long-term plan to build a functioning common legal space.

To build a more durable strategy to protect the rule of law in Europe, the EU should change the way it thinks about the relationship between EU values, the Union’s legal order and its member-states’ rights and obligations. Both the internal market and the area of freedom, security and justice work because there is an implied trust that all national courts follow the same standards. Once this is no longer the case, membership of not only the single market, but also the EU’s borderless area of Schengen become endangered. The Union should make that link clear.

For that, it could draw inspiration from both the European Semester and the recovery fund to come up with a ‘European Justice Semester’ that would help anticipate problems, hold countries accountable and set up a dialogue between national capitals and Brussels. Much like the recovery fund, this plan would require national justice strategies which should be adopted in agreement with Brussels. And much like the European Semester, it would also include recommendations – which would, unlike those of the Semester, have to be binding. Ultimately, a warning procedure could apply to countries which have been found to repeatedly deviate from the standards. Such a procedure could end with a temporary ‘freezing’ of the recalcitrant country’s participation in certain EU laws, like the European Arrest Warrant.

The pandemic and the war in Ukraine had an unexpected silver-lining for the EU’s rule of law struggle. It is time for the Union to upgrade its battle plans accordingly. By streamlining some of the elements of the recovery fund into its rule of law toolbox and ensuring that attacks on democratic standards have serious consequences in other areas, the EU will end up with a more consistent, more effective strategy. It is not always about the money, stupid.

Camino Mortera-Martinez is head of the Brussels office and Sander Tordoir is senior economist at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment