The gap between the 'Brexit reset' rhetoric and the reality

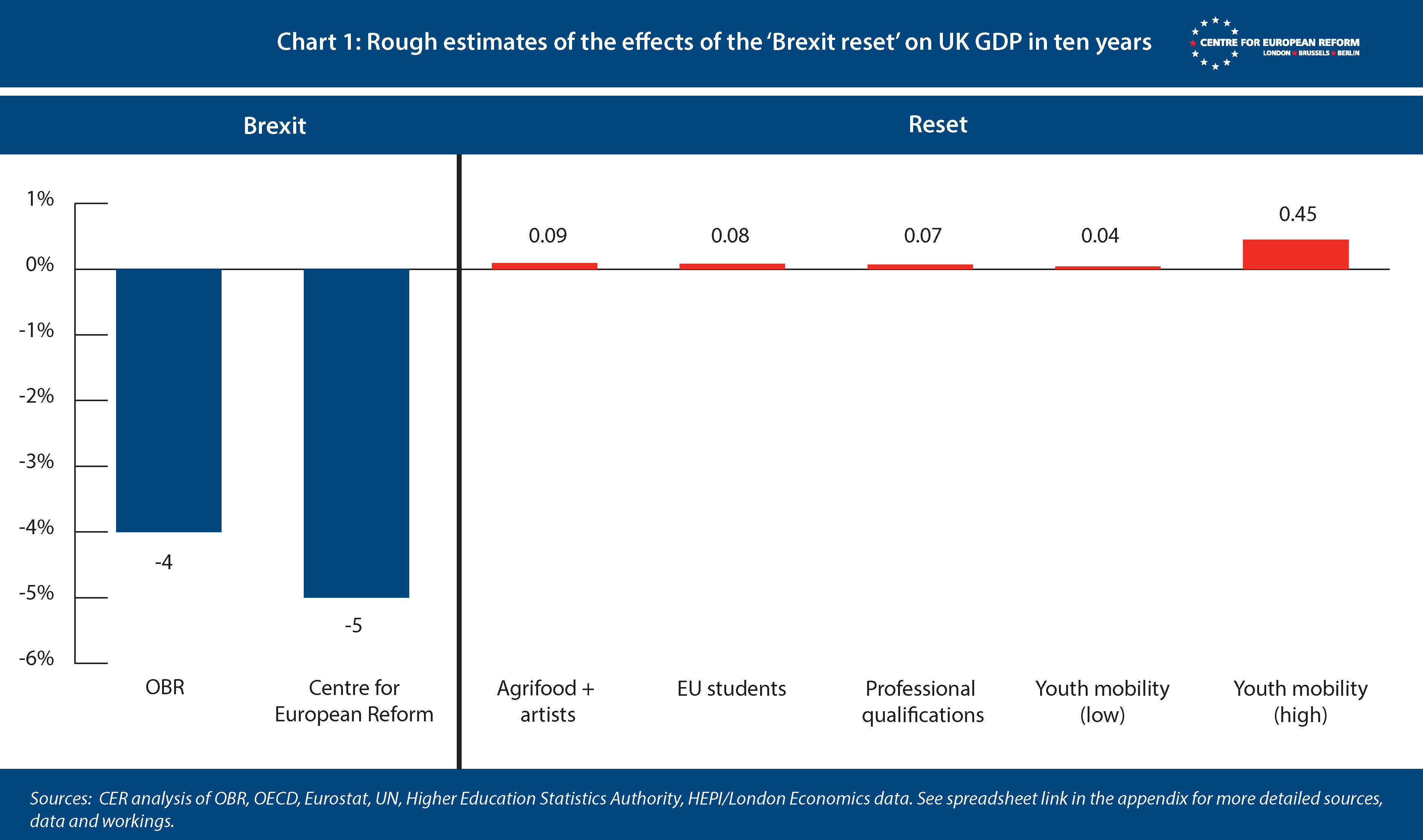

Rough-and-ready calculations based on the stated demands of the UK and EU suggest the reset might raise Britain’s GDP by 0.3-0.7 per cent.

According to the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s fiscal watchdog, Brexit will reduce productivity by 4 per cent in the long run, compared to a Britain that remained in the EU. My analysis found the reduction in GDP to be around 5 per cent by the second quarter of 2022. Prime Minister Keir Starmer acknowledges that Brexit has been costly, at least in the form that the Conservative party chose. He promises to “make Brexit work” and to “tear down” the trade barriers that Brexit imposed, to offset some of those costs, while insisting Britain will not rejoin the single market, customs union or the EU itself. But how much will his planned ‘reset’ of UK-EU relations deliver on these promises?

I have conducted a rough-and-ready set of estimates of the benefits of the ‘reset’. These are based on the stated aims of both the UK and the EU so far, using assumptions and historical economic relationships that are inevitably crude guides to the future, but which offer a reasonable guide to the magnitudes involved.

In their manifesto, Labour promised to negotiate:

- a ‘veterinary agreement’, which would seek to reduce barriers to trade in food and agricultural products (which would entail alignment with EU animal and plant health rules, otherwise known as sanitary and phytosanitary rules, or SPS)

- help for performing artists to be able to conduct tours in the EU (the current visa and transport rules make touring bureaucratic and expensive)

- mutual recognition of professional qualifications, so that UK and EU professionals can more easily move across jurisdictions to work.

For its part, the European Commission published a proposal for youth mobility between the EU and the UK in April 2024. It sought negotiations to allow:

- UK and EU 18-30 year-olds to be able to migrate for work, study or other purposes for four years

- UK and EU students to pay the same tuition fees as home students in each other’s jurisdictions.

The UK has already rejected some of these negotiating demands. The British government opposes such an expansive youth mobility scheme (although not a youth mobility scheme in general, saying before the election that it merely “has no plans” for one). The EU is reportedly drawing up an alternative proposal for a slimmed down version. Other negotiating demands might be put on the table, and the UK’s unspecified plans for closer co-operation on energy might raise output. But if we take the proposals from the two sides at face value, how much might they offset the cost of Brexit?

Chart 1 sets out the estimated effects of the reset on UK GDP in the long run. The trade impact from a veterinary agreement and allowing more artists’ tours would raise GDP by about 0.1 per cent in ten years. While an SPS agreement would raise exports and imports in agri-food substantially, that sector is a small part of the economy, so the effects on output are tiny. This is even more true for performing artists. The effect of easing barriers to migration might be somewhat larger, with youth mobility and easier recognition of qualifications raising GDP by between 0.1 and 0.5 per cent. And allowing EU students to pay UK fees to study at British universities might raise GDP by about 0.1 per cent, because more EU students would move and spend money in the UK. It is worth noting that the EU demands for young people may raise UK GDP more than Britain’s demands on trade and the easier movement of professions.

If we add those potential benefits up, we obtain an overall improvement to UK GDP between 0.3 and 0.7 per cent over ten years. That overall effect is not nothing, and both sides should pursue these gains.

But as the stated positions of the two sides stand, the potential economic benefits are likely to be even smaller. Britain is unwilling to accept an expansive youth mobility scheme, which will mean fewer young people working in Britain, and therefore a smaller economy. The government has also signalled opposition to EU students paying home university tuition fees – which are about £12,000 lower a year than international ones. That is despite a clear drop in EU students studying in the UK since Brexit – around 55,000 – and the spending of EU university students standing at around £61,000 per student over the course of their studies, according to the Higher Education Policy Institute and London Economics (that figure does not count spending on tuition fees – more details in the appendix below). For its part, the EU has been wary of mutual recognition of professional qualifications because the UK has a comparative advantage in this sector, and it would put European domestic professionals under greater competitive pressure.

Far from “tearing down” barriers to trade and migration, then, Britain’s proposed reset is likely to do little to offset the costs of Brexit.

Appendix

A spreadsheet with the data and workings can be found here.

Here is a summary of the crude but rough-and-ready methods I have used.

Veterinary agreement

Jun Du and colleagues have estimated the effect of an SPS deal, finding that it would raise UK agri-food exports by 22.5 per cent and imports by 5.6 per cent. That rise in exports/imports – about £3 billion each – would raise total UK trade in goods and services by 0.3 per cent. Using the OBR’s analysis as a ready-reckoner, which suggests a 15 per cent fall in trade as a share of the economy reduces long-run productivity by 4 per cent, we find that a 0.3 per cent rise in trade raises productivity (and hence GDP) by 0.1 per cent.

Helping touring performing artists

In 2022, Britain’s exports of ‘creative, arts and entertainment activities’ to the EU were 32 per cent below their 2019 level. Its exports to the rest of the world were 21 per cent below. Taking the difference – about £110 million in exports, and applying the OBR rule-of-thumb above, we get a rise in GDP of 0.008 per cent. This is probably an over-estimate, as the exports of ‘creative, arts and entertainment activities’ series includes more activities than tours of performing artists.

The UK’s imports of these services from both the EU and the rest of the world were much smaller and more volatile, so the effect of imports on GDP is negligible.

Mutual recognition of qualifications

The EU’s Regulated Professions Database shows that, in 2023, 32,000 professionals used the EU’s system for recognising their qualifications. Applying the UK share of the EU labour market to that – 16 per cent – we arrive at 5,000 UK professionals making use of an agreement to access EU labour markets a year, if the UK were able to use the system.

The same database shows that, in 2019, 9,500 EU professionals used the system to have their qualifications recognised in the UK. This leaves a net immigration to the UK of 4,500 professionals. In reality, the effect of the agreement on migration would probably be smaller, as professionals can have their qualifications recognised in both the UK and many EU member-states, although it is more difficult without a mutual recognition agreement.

The OBR estimates that one million more immigrants in the UK raises GDP by around 1.5 per cent. Applying that ratio to our 4,500 annual figure, over ten years UK GDP would be 0.07 per cent higher.

Youth mobility

Forecasting migration is notoriously difficult, because it depends on employment and wage conditions in sending and receiving countries. I have produced two estimates to offer a range.

The low estimate takes the average annual growth rate of 15-29 year-old EU citizens in employment in another EU country between 2014 and 2023. It has grown by 0.8 per cent on average each year. That gives us a sense of current movement of young people within the free movement area of the EU. If we apply that to current numbers of EU 18-29 year-olds in payrolled employment in the UK, according to the HMRC, we would see around 40,000 more young people in work in the UK in ten years’ time.

The UK data for young people in the EU is much patchier. According to an ONS study, in 2017 there were 85,000 British 15-29 year-olds living in the EU. Extrapolating forward from the EU growth rate above, in ten years’ time there would be an additional 12,000 in the EU.

Applying the OBR rule-of-thumb for immigration and output to the net figure of 26,000, GDP in ten years' time would be 0.04 per cent higher.

The high estimate takes the growth rate of EU young people working in the UK between 2014 and 2017 – i.e. until the vote to leave and the fall in sterling meant immigration to the UK from the EU dried up, and led many EU citizens to leave the country. That was 5.9 per cent annually. For UK young people in the EU, I used the growth rate of UK nationals as a whole living in the EU between 2000 and 2015, according to the UN’s five-yearly data. That was 3.4 per cent.

The net immigration that results to the UK would be around 31,000 a year, which, using the OBR ratio, would entail a rise in GDP of 0.45 per cent in ten years.

EU students paying home fees

According to Higher Education Statistics Authority data, the number of EU students studying at UK universities fell from an average of 149,000 between 2018/9 and 2020/1, to 95,000 in 2022/3. If we assume that the fall is entirely down to EU students having to pay higher, international fees, the EU’s proposal would entail around 55,000 extra EU students in the UK a year. That would mean the loss of fees of approximately £12,000 per existing EU student. But it would raise economic activity because students spend money on rent and other goods and services in the UK. According to the Higher Education Policy Institute and London Economics, because of the spending of students and visiting families, each EU student brought in £61,000 each in non-fee income to the UK over the course of their studies. Taking that additional spending, and subtracting the loss of international fee income from the 90,000 EU students who came despite the rise in fees, we end up with an increase in GDP of 0.08 per cent.

John Springford is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment