The EU's troubled leadership: You get what you pay for

Recent gaffes by Ursula von der Leyen and Josep Borrell, over COVID-19 vaccination roll-out and Russia policy respectively, have irritated member-states. But governments are ultimately responsible for the EU’s leadership woes, and they need to make the effort to fix them.

The EU’s top leadership has got off to a bad start in 2021. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen carries only a small share of responsibility for EU member-states’ slow progress in vaccinating their populations against COVID-19, but her attempts to blame others have not gone down well. Moreover, the Commission’s panicked attempt to close Ireland’s border with Northern Ireland to prevent the export of vaccines to the UK has reignited tensions with Britain over the Northern Ireland Protocol of the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement. Meanwhile, the politically risky visit to Moscow by EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HRVP) Josep Borrell was widely described as humiliating: the Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, accused EU leaders of lying about the poisoning of Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny and described the EU as an unreliable partner – while Borrell stood silently next to him at a press conference. The Russians underlined their contempt for Borrell by declaring three EU member-state diplomats personae non gratae while he was meeting Lavrov.

The EU's top leadership has got off to bad start in 2021. But if member-states' governments are wondering who appointed such unsuitable people to such important positions, they do not have far to look.

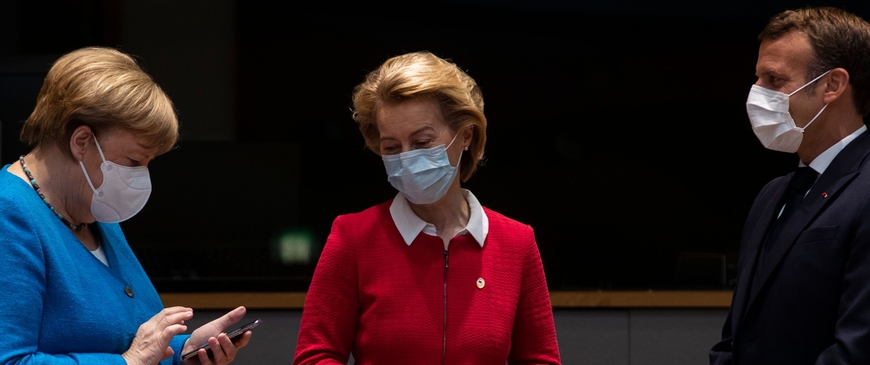

But if member-states’ governments are wondering who appointed such unsuitable people to such important positions, they do not have far to look. After three days of intense negotiations in the European Council in the summer of 2019, both Brussels-watchers and the nominees themselves were surprised by the names put forward for the EU’s top jobs: German defence minister von der Leyen for Commission President; former Belgian prime minister Charles Michel as European Council President; Spanish foreign minister Borrell as HRVP; and (the least surprising) Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Christine Lagarde as President of the European Central Bank.

None of the EU’s new leaders were first choices – with the exception of Lagarde. This had little to do with their seniority and experience, and everything to do with the ever-complex world of EU politics, where consensus, institutional turf wars and quotas often trump political strategy. The combination of factors that have to be considered make choosing the right candidates for the job difficult at the best of times; at worst, it weakens the EU both internally, by pitching governments against the Brussels institutions, and externally, by failing to show a coherent front to the world. The current problems with the EU leadership are a direct result of the inability (or unwillingness) of European governments to agree on a team that had a clear and strong vision for Europe.

The appointments came about because of the interaction between the results of elections to the European Parliament in May 2019 and the Spitzenkandidaten process, whereby the nominee of the largest political grouping in the incoming Parliament is supposed to become Commission President (the CER has long criticised the process for upsetting the balance of power between the European Council and the European Parliament in favour of the latter, and for failing to deliver promised democratic legitimacy). The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) won the elections, but its Spitzenkandidat, Manfred Weber, was so unpopular that even an EPP-dominated European Council rejected him. Some leaders from the EPP family, including Angela Merkel, would have backed the Spitzenkandidat of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), Frans Timmermans, a former Dutch foreign minister and Vice President of Jean-Claude Juncker’s Commission. Most wanted the job for the EPP, however. Timmermans was also opposed by Central European countries which objected to his attempts to tackle violations of the rule of law in Hungary and Poland.

With Timmermans out of the race, European leaders rushed to find a compromise candidate. Von der Leyen, a francophone German conservative, was acceptable to both Germany and France, to the EPP from whose ranks she was drafted, and to the Visegrad countries. Her appointment created a domino effect: with the Commission going to a German conservative, Southern socialists and the liberals needed top jobs, too. Enter Borrell and Michel.

It was never going to be easy for von der Leyen, Borrell and Michel to steer a hesitant EU through growing tensions between China and the US; to deal with Britain’s exit from the bloc; or to stop democratic backsliding inside the Union, to cite three of the many challenges the EU faces. The coronavirus pandemic threw an extra complication into the mix.

It was never going to be easy for von der Leyen, Borrell and Michel to steer a hesitant EU through growing international tensions. The coronavirus pandemic threw an extra complication into the mix.

Unlike the Commission presidency, Borrell and Michel’s positions are theirs to shape. Both jobs are relatively new (the Lisbon treaty created them ten years ago), and the degree to which they are influential depends largely on who fills them. For now, Michel has kept rather quiet. He did not try to position himself as a broker between the EU and the UK, even as Britain left the EU; nor has he had any major role in pandemic management and communication. Unfortunately for him, his first year in office will be remembered – if at all – for his very public faux pas when he unveiled a project to set up an EU institute to train imams as a way to combat extremism – a French idea seemingly oblivious to the dangers of conflating terrorism and Islam.

Von der Leyen and Borrell are having a more torrid time than Michel. Von der Leyen’s leadership style is different from the bonhomie of her predecessor, Luxembourg’s Jean-Claude Juncker. Unlike him, she is not a veteran of EU politics. She relies on a tight-knit circle of advisers, many of whom are unfamiliar with Brussel’s palace intrigues themselves – perhaps because they came directly from her Berlin ministerial office. She is also having to work with the most divided European Parliament in EU history. Until 2019, the Parliament was an essentially bipartisan institution in which its largest parties (the EPP and the Socialists) worked together and alternated in leading it. Now they need the support of other groups (in practice, the Greens-European Free Alliance or the liberals of Renew Europe) to assemble a majority.

This has made von der Leyen’s job tricky: in order to win support for her appointment from groups as different as the Greens and the Conservatives (the Parliament has the right to reject a presidential candidate, and to fire the President and the Commissioners once in office), she made a long list of promises that she was bound to break. Von der Leyen cannot push laws through a parliament that disagrees with her. And the opinion of European parties, in turn, depends largely on what happens in national politics back home.

Despite the obstacles, von der Leyen has spearheaded two of the Union's most ambitious projects to date: the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund; and the bloc’s joint vaccine procurement. The former was a good example of von der Leyen’s way of doing things, with hurried communiqués and last-minute decisions, but it paid off in the end. For the first time the EU agreed on a common fiscal response to an economic shock, creating a recovery fund endowed with money borrowed from financial markets.

Despite the obstacles, von der Leyen has spearheaded two of the Union's most ambitious projects to date: the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund; and the bloc's joint vaccine procurement. The latter has gone down to the drain.

Joint vaccine procurement, however, has been less successful. The vaccination roll-out has been slow and plagued with problems. EU governments outsourced vaccine purchases to the Commission in the hope of avoiding disparities in vaccination rates between member-states. Once doses are delivered, though, it is up to the member-states to decide who to vaccinate and when. Von der Leyen and her team quickly put together a purchasing strategy against the background of a world race to secure jabs. The plan had gaps, in particular a lack of enforcement mechanisms in case pharmaceutical companies did not deliver on their promises. And initial problems in manufacturing chains led to delays and vaccine shortages.

As a result, EU countries have made little progress in vaccinating their citizens: as of late February, Malta, the member-state with the bloc’s highest vaccination rate, had given the necessary jabs to only 4.7 per cent of its population. Von der Leyen failed at first to acknowledge and then explain the terms of the Commission’s deals with vaccine producers and why these might result in shortages. Astonishingly, she also tried to blame the EU’s trade officials for the fracas. She later apologised but the damage was done.

The EU’s vaccination problems caused collateral damage, when EU officials publicly accused the British-Swedish pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca of delivering vaccines earmarked for the EU to Britain first, helping the UK’s successful vaccination campaign at the expense of the EU. The Commission then announced that it would trigger Article 16 of the Northern Ireland Protocol to the UK Withdrawal Agreement, imposing export controls on vaccines moving from the EU to Northern Ireland. The article authorises the parties to restrict the free movement of goods in cases of “economic, societal or environmental difficulties”, but is intended as an emergency measure, not something to be used lightly. In this case, the Commission took both the UK and Irish governments by surprise. Facing criticism from both, it quickly backed down; but the incident exposed the shortcomings of von der Leyen’s decision-making process, in which no-one with an understanding of the sensitive Irish border issue had been consulted.

Von der Leyen has emerged badly bruised from the vaccine showdown. While there are things she could not control (if a manufacturing plant is ill-equipped for massive vaccine production, there is little the Commission President can do about it other than wait for it to be fixed), her managerial style has angered national capitals and her own team alike. And because vaccine shortages have a very tangible impact on people’s lives, European governments have been quick to lay the blame for the mishaps on von der Leyen (whom their voters cannot remove from office) rather than themselves (more vulnerable to voters’ anger). The Commission’s leadership handled the problem of vaccine shortages poorly, and unnecessarily gave the moral high ground to the UK by appearing ready to impose a hard border in the island of Ireland, when the EU had spent four years telling the UK that such a border would be totally unacceptable.

The Commission’s leadership handled the problem of vaccine shortages poorly, and unnecessarily gave the moral high ground to the UK by appearing ready to impose a hard border in the island of Ireland.

Borrell, notably opinionated, is possibly in the most uncomfortable position of the EU’s leaders. By labelling her team ‘the geopolitical Commission’, and creating units in charge of dossiers with significant foreign policy implications (like a new department for digital matters), von der Leyen made it clear who the boss of the bloc’s foreign policy was going to be. Clue: not Borrell.

This may, in part, help explain Borrell’s shambolic visit to Moscow on February 5th. It was a badly timed trip – Navalny had just been jailed on returning from Berlin, where he was treated for poisoning carried out by Russian security agencies. Borrell seemed ill-prepared for Lavrov’s predictable claims that any problems in the EU-Russia relationship were the fault of the European side. There was a stark contrast between Borrell’s passivity and the willingness of the Finnish foreign minister, Pekka Haavisto, to contradict Lavrov when speaking to the media after their meeting in St Petersburg on February 15th.

EU governments are upset about the way von der Leyen has managed the vaccine fiasco. Some are livid at Borrell’s seemingly free-standing diplomacy. But they are simply getting what they paid for. In patching together a leadership team with no clear common plan or direction, leaders were setting themselves up for failure. Von der Leyen and Borrell should learn from their mistakes. The Commission president should be more open to outsider opinions and make better use of seasoned EU staff. Borrell, for his part, needs to have a better understanding of those that wish the EU ill – first, by recognising that they exist.

But none of this will matter if member-states do not pull their weight by providing the EU leadership with the necessary support to shore them up in areas where they are weak. Ultimately, EU governments should be more strategic the next time they appoint their leaders. In 2024, everyone should take the whole process of selecting EU leaders more seriously – for example by coming up with slates that take into account quotas and politics but are also cohesive and well thought through. EU governments need to pick candidates who can, and want, to do the job, not people they wish to push out of national politics. If governments simply continue to play the game of deflecting blame to Brussels when it suits them, that will only help Europe’s anti-EU forces and their foreign supporters – including Vladimir Putin.

Camino Mortera-Martinez is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Until there is a system whereby commissioners are selected based on merit by the EU President & not because country X is entitled to a commissioner then the same low caliber people will continue with EU credibility further damaged.

Add new comment