The EU and the rule of law: Much movement, little change

The EU has strengthened its tools to defend the rule of law, but it needs to start applying them more forcefully.

During her first term of office, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen grappled with the twin rule of law crises in Poland and in Hungary. As her second tenure begins, some of the protagonists have changed. Poland’s new government, led by Donald Tusk, is strongly committed to the rule of law. Viktor Orbán’s Hungarian government, however, continues to dismantle democracy at home, and challenges to the rule of law are emerging in other countries. These include threats to the judicial systems and to media pluralism in Slovakia, Italy, Bulgaria and Greece.

Upholding the rule of law is crucial for the EU: citizens and companies thrive in an environment where no one is above the law, including lawmakers and leaders. Impartial justice is essential for the functioning of the EU single market; transparency and accountability promote trust and political cohesion among member-states.

Over the past five years, the EU’s enforcement mechanisms have improved, but they have failed to prevent or remedy rule of law problems. However, this does not mean that the EU is helpless in the face of challenges to the rule of law – just that it needs to use its tools more quickly and effectively. In addition, commitment to reforms and buy-in by national politicians, whether in opposition or in government, are important elements of solving the rule of law conundrum.

Over the past five years, the EU’s enforcement mechanisms have improved, but they have failed to prevent or remedy rule of law problems.

What has happened over the past five years?

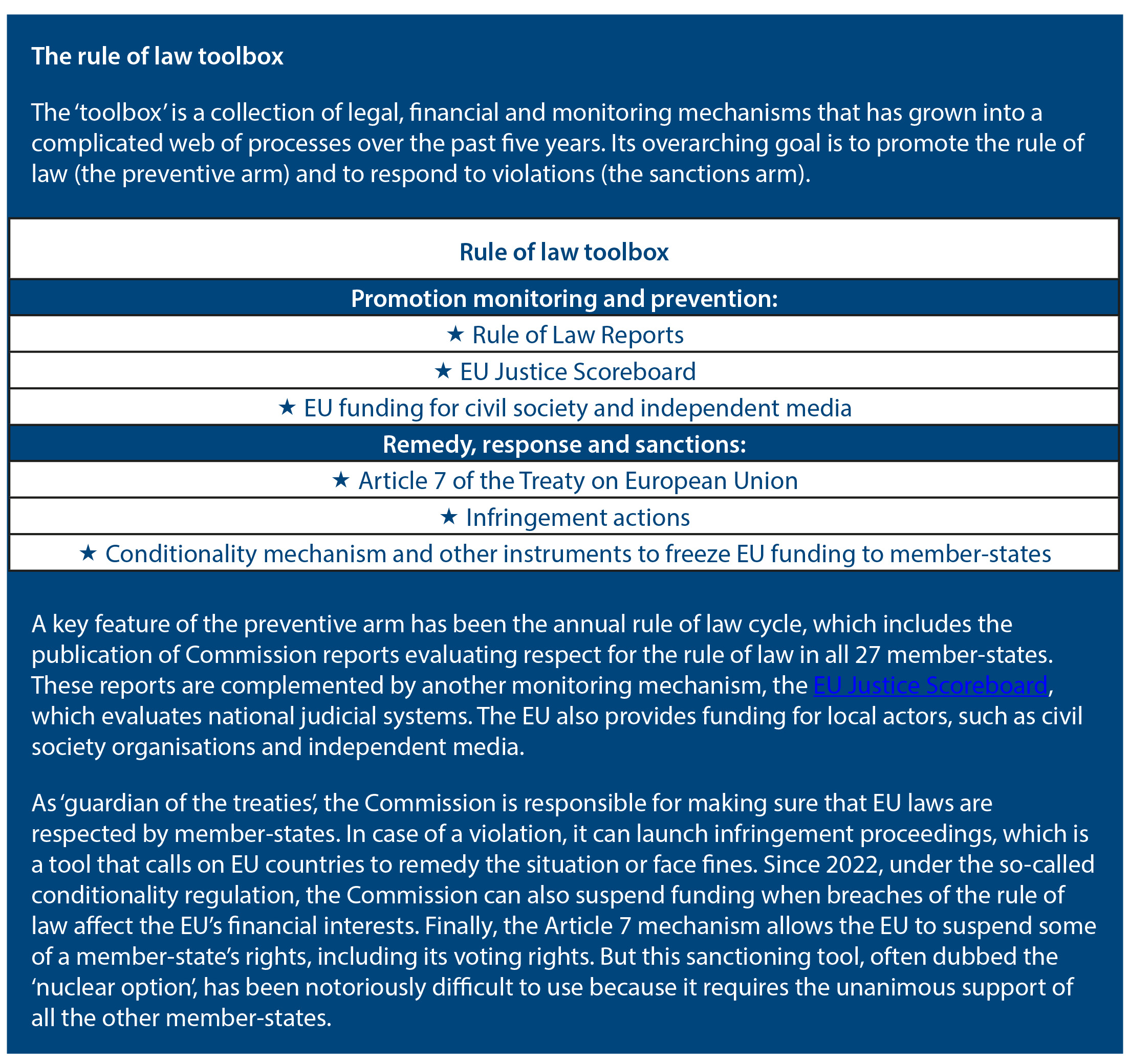

In her 2019 Political Guidelines, Ursula von der Leyen declared that, “There can be no compromise when it comes to defending our core values.” The guidelines promised tougher enforcement of the rule of law, linking more EU funding to respect for the rule of law, and full implementation and expansion of the so-called rule of law toolbox (see box below).

The EU has strengthened both the preventive and the sanctions arms of the toolbox since 2019.

Promotion, monitoring and prevention

The Rule of Law Reports have evolved, taking into account criticism from the expert and NGO communities. The 2024 edition, compared with 2020, contained not only country-specific recommendations but also monitored progress in their implementation. Both are significant improvements. The report also covered four new candidates – Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

The reports, however, have failed to sufficiently confront the most problematic cases, namely Hungary, and Poland before its change in government in late 2023. First, they used overly diplomatic language. And second, the reports applied the same, often formalistic benchmarks to democracies and to the two countries, where the governing party had captured state institutions while keeping the trappings of democracy. The application of the same criteria can be misleading: the adoption of an anti-corruption strategy, for example, may be laudable in a well-functioning democracy but makes little difference in a country where corruption flows from the top. The Rule of Law Reports therefore inappropriately drew parallels between qualitatively different cases, diminishing the gravity of the Hungarian and Polish situations.

The EU Justice Scoreboard has suffered from the same flaws but to a lesser extent, given its narrow, technical focus on national judicial systems and its emphasis on gathering additional data for assessing member-states’ adherence to the rule of law. It has had less of a prominent role in the toolbox.

The EU has increased the amount of funding available to promote the rule of law. The Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values (CERV) programme has grown to €1.55 billion in the ongoing seven-year budget cycle, up from €439 million in the years 2014-2020. Some of that money has specifically supported civil society organisations working on the rule of law. Funding for promoting pluralism and sustainability in the media has also increased – even if the exact amount has been hard to quantify due to the lack of EU-wide data.

Remedy, response and sanctions

There has been no movement on the Article 7 procedure, which is the main tool for holding countries accountable if they breach EU values. For most of the past five years, both Hungary and Poland remained stuck in the first stage of the process, with little progress beyond regular hearings on the state of play. In Hungary’s case, member-states did not take additional steps towards determining that there is a “risk of a serious breach” of EU values, the first step of the procedure. Nor was there any movement towards establishing the existence of a “serious and persistent breach” – the second step – despite the fact that the country has been subject to the Article 7 procedure since 2018. When it comes to Poland, the first Von der Leyen Commission closed the procedure in May 2024, just before the end of its term. The decision came after Poland’s newly elected government proposed plans to remedy violations of the rule of law.

The number of infringement proceedings – the other enforcement tool in the hands of the Commission – has plummeted since the early 2000s, negatively impacting rule of law enforcement. According to a 2022 study the change was the result of ‘forbearance’: the Commission preferring dialogue over infringements to avoid losing countries’ support for its policy proposals. This trend has continued in recent years, although there were some important exceptions. These included record-high fines handed out to Poland in 2021, for the government’s attempt to discipline judges, and to Hungary in 2024, for violating the rights of asylum seekers.

The most important development of the past five years was the introduction of the so-called conditionality regulation, and the subsequent suspension of EU funding linked to rule of law violations. This step allowed the EU to overcome inertia against rule-breakers. In a first, the Commission froze €6.3 billion of Hungary’s cohesion funds in late 2022 – of which the country is about to permanently lose roughly €1 billion by the end of 2024 if it fails to comply with ‘super milestones’ on corruption and public procurement. An additional €9.6 billion of grants and loans under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the EU’s post-Covid funding, also remains frozen due to Hungary’s non-compliance with corruption and audit rules.

The conditionality regulation and the suspension of funding to Poland and Hungary were major steps towards protecting the rule of law.

The Commission has also triggered a previously unused instrument to rein in rule-breakers, the so-called horizontal enabling conditions, which led to the largest chunk of suspended funding. In 2018, the EU incorporated the Charter of Fundamental Rights into the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR), the EU’s rulebook for delivering funds to poorer regions. This allowed the Commission to freeze disbursements to countries that fail to protect fundamental rights, such as freedom of speech or equality. In 2022, Brussels froze €75 billion destined for Poland and €22 billion allotted to Hungary under this mechanism.

These steps demonstrate that the Commission put a real effort behind the use of conditionality. But the suspensions did not last. In 2023, the Commission released €10.2 billion to Hungary following the passing of some judicial reforms and to avoid an Orbán veto during a crucial European Council vote on support for Ukraine. It released all funds to Poland after the new government announced its plans to respect the rule of law in 2024.

What worked and what did not?

The strengthening of the rule of law toolbox since 2019 has yet to translate into improvements on the ground in EU member-states. The past five years have been characterised primarily by stagnation, according to the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index or Freedom House’s Freedom in the World reports.

Neither arm of the rule of law toolbox has had a significant impact. Stronger monitoring under the Rule of Law Report has yet to prevent deterioration, in part because there are no direct consequences when countries fail to follow up on recommendations. Additionally, ‘politicisation’ seems to have further undermined the report’s effectiveness – this year, for example, the publication of the reports was delayed, reportedly to avoid upsetting Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni before von der Leyen’s re-election.

The EU’s rule of law toolbox is comprehensive, complicated and large enough to be useful – but what is often missing is the political will to use it effectively.

Von der Leyen promised tighter enforcement of the rule of law five years ago, but there was no increase in the use of infringement proceedings and no movement on Article 7. The introduction and use of the conditionality regulation and the suspension of money under the CPR were major steps forward. Yet, they have failed to ‘bite’ – the Commission released €10.2 billion to Hungary just as the country had run out of EU funding, thus avoiding any direct impact on the economy. Finally, the increase of EU funding to civil society and independent media is promising, but it is too early to tell how much impact it will have.

During the publication of the EU’s 2024 Rule of Law Report, Commissioner for Values and Transparency Věra Jourová highlighted two success stories: the closing of the Article 7 process against Poland and the end of a five-year-long deadlock on judicial appointments in Spain. In Poland, financial and legal sanctions against the country played a crucial role in the 2023 election campaign. The opposition claimed that the Law and Justice (PiS) government was preparing to leave the EU. In this way, EU pressure may have contributed to the defeat of PiS and the beginning of the restoration of the rule of law. In Spain, the EU also played an important, and somewhat unusual, role as mediator between the governing and opposition parties. A lack of agreement between the two had led to a deadlock at the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), a body overseeing judicial independence and appointments. This resulted in a significant number of vacancies in the judicial system, threatening its effectiveness. The Commission’s mediation helped to unblock the appointments and put an end to the crisis.

Yet, as Jourová highlighted, there was little progress in the three other areas covered by the reports. When it comes to corruption, the EU’s average score on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) declined for the first time in almost a decade in 2023, demonstrating an erosion of checks and balances and declining trust in institutions. It did not help that the European Parliament suffered its own corruption scandal last year, the so-called Qatargate. The adoption of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) will help to safeguard the independence of public media, improve ownership transparency and the safety of journalists, as well as protect against excessive ownership concentration. However, it will only come into effect starting next spring. Finally, in the area of checks and balances, civil society continues to face attacks and restrictive laws, as demonstrated by the recent adoption of legislation banning LGBT+ ‘propaganda’ in Bulgaria.

When it comes to the EU’s biggest rule of law headache, Hungary’s slide into autocracy, the problem certainly has not gone away. If anything, the situation has worsened as Prime Minister Viktor Orbán adopted an increasingly unco-operative stance within the EU (and NATO) – both to obtain concessions and to embellish his image at home. Major threats to the rule of law have also emerged in Slovakia, where Prime Minister Robert Fico has attempted to bring public media, cultural institutions and the prosecution of corruption cases under political control. In response, the Commission is looking into triggering the conditionality mechanism against the country. Finally, judicial independence has long been fragile in Bulgaria, where infighting over reforms triggered the sixth election in three years, and in Greece, which has been reeling from a spyware scandal, with allegations of illegal use of such tools by the government against politicians and journalists. The media have also faced attacks in these countries as well as in Italy, where smear campaigns and onerous lawsuits against journalists have undermined their ability to report freely.

Priorities for the next Commission

Despite the lack of significant impact, there is no need to throw the baby out with the bathwater – the tools at the Commission’s disposal to defend the rule of law are not useless.

First and foremost, the Commission should use the expanded toolkit more quickly and effectively, rather than playing a game of constant catch-up. Brussels should respond to the first signs of a deterioration in democracy and rule of law in a member-state and, where necessary, launch infringement actions, trigger the conditionality mechanism or advance Article 7. The Commission has a lot of discretion and leeway to use the infringement and conditionality mechanisms more assertively. And while a final decision under Article 7 is up to the member-states, the Commission should still consider resorting to it earlier and more quickly. Robust enforcement would help to avoid complaints and lawsuits by the European Parliament for failing to hold rule-breakers accountable.

Second, the Commission should increase transparency to avoid accusations of politicisation. Legal questions cannot be separated from their political context. But the best way to avoid the appearance of politicisation is to communicate transparently and to adhere to deadlines. In allegedly delaying the publication of the 2024 Rule of Law Report to avoid upsetting Italy, and in timing the release of funds to Hungary to coincide with a vote on EU support for Ukraine, the Commission has failed both tests.

Third, avoiding politicisation should not mean forgoing engagement with national political actors. The EU has accomplished most when there was receptivity and commitment from national politicians. This was the case in both Poland and Spain, where the opposition (in Poland) and both parties (in Spain) showed willingness to engage and to remedy the situation. This suggests that the solution to most rule of law problems can be found, ultimately, within the member-states. The question is how the EU can nudge that forward without getting embroiled in accusations of interference in domestic matters.

Fourth, with sufficient political will, the current toolbox is already comprehensive, complicated and large enough to be useful. Yet, as we have seen, the introduction of a new instrument (the conditionality regulation in 2022), is sometimes needed to trigger the use of an already available tool (the ‘horizontal enabling conditions’ in the CPR). Expanding the use of conditionality to other parts of the budget and building a closer link with the Rule of Law Reports, as proposed by the new Commission, could lead to similar synergies and to more robust enforcement.

Internal and external threats, such as climate change, Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s industrial assertiveness, will continue to draw attention and resources away from strengthening the rule of law inside the EU. Yet, to confront these challenges, the Union cannot afford to ignore the state of democracy at home. Tolerating rogue member-states will fracture EU cohesion and undermine the EU’s capacity to act. And with enlargement on the horizon, one thing is clear: if the enforcement of the rule of law is lacking in an EU of 27, it will be woefully inadequate for an EU of 35 of more.

Zselyke Csaky is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment