Will EU enlargement create new models for the EU-UK relationship?

- Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine has given new momentum to EU enlargement. Ukraine and Moldova have started accession negotiations, and EU leaders regularly refer to enlargement as a geopolitical necessity.

- The enlargement process is pushing the EU to think creatively about how to work more closely with candidate countries before accession. The Union is increasingly embracing the notion of phased enlargement. In parallel, the EU is exploring new ways of deepening defence and security co-operation with candidate countries.

- This paper considers how enlargement could affect the EU-UK relationship. Specifically, it focuses on how the EU’s embrace of phased enlargement may lead it to develop models of association for countries that do not want to become full members, or that cannot do so.

- There are several models for what associate membership of the EU could look like. The most ambitious model could resemble an upgraded version of Norway’s relationship to the EU. Associate countries would be de-facto full members of the single market, including free movement, and have some decision-shaping rights. Unlike Norway, they would also be involved in extensive consultations with the EU, including by attending leaders’ meetings.

- The least ambitious model for associate membership would entail a much more limited level of integration. Associate members would align with EU law in some sectors only. They would not have decision-shaping mechanisms or implement free movement and consultations at all levels would be less frequent and intense. However, there could still be significant defence co-operation with the EU.

- If the EU developed an associate membership model, the implications for UK-EU relations would depend on what the model looked like in practice. The Norway+ model is unlikely to appeal to the UK so long as its red lines remain those of rejecting the single market, free movement, and the customs union. If the UK revised these, then full EU membership, if available, could seem like a more tempting option.

- Conversely, if EU associate membership was a minimalist model, the implications for the EU-UK relationship would probably be significant. The UK is likely to be very interested in a model that allows sectoral integration without free movement. The EU’s willingness to offer the UK such a model would depend on the broader state of bilateral ties, and on whether the development of a greater variety of relationships with non-EU partners eases the EU’s concerns about British cherry-picking.

- Even if the EU does not develop a fully-fledged associate membership model, the scope for EU-UK defence co-operation could grow if the EU continues to strengthen defence co-operation with accession candidates. The more defence is seen as a self-contained area of co-operation, insulated from broader issues, the greater the prospects of UK-EU co-operation.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is reshaping European politics. One consequence is the new momentum behind EU enlargement. Three years after Russia’s invasion, Ukraine and Moldova have joined Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Türkiye in the process of negotiating accession to the EU. Another effect of Russia’s invasion is greater pressure for closer EU-UK co-operation, particularly in defence.

This paper considers how enlargement may affect the EU-UK relationship. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and other EU leaders refer to enlargement as a “geopolitical imperative”.1 In practice, however, EU enlargement – both to Ukraine and Moldova and to the countries of the Western Balkans – is at risk of stalling again. Many candidates face significant internal challenges in meeting the requirements of EU membership, especially in terms of fighting corruption and strengthening the rule of law.2 On the EU side, there is still substantial caution about enlargement, manifested for example in the notion that the EU must reform before it can enlarge.

The challenges faced by many candidates, combined with scepticism on the EU side, mean that that there is a real risk that enlargement will stall. To avoid that, the EU is increasingly emphasising the notion of phased or staged enlargement. The idea is that candidate countries can be gradually integrated into different EU policy areas over time. The EU may also develop alternatives to fully-fledged membership, for example a status of associate member as an intermediate destination on the way to membership. That could have important implications for the way the EU deals with other neighbours, including the UK.

The paper will first consider what phased enlargement means in practice and what an associate membership of the EU could look like, including how it might differ from existing EU models for dealing with close partners like Switzerland and Norway. Secondly, the paper will assess what the benefits of such a status would be for the EU and its members, and for the partner countries. Finally, the paper turns to the question of what such a model would mean for the EU-UK relationship.

From phased enlargement to new membership models?

The question of enlargement is at the forefront of EU political debates, in particular in relation to Ukraine’s accession. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine the Union recognised enlargement as a “strategic priority”.3 The war has convinced many member-states that enlargement is a geopolitical necessity. Enlargement is one of the EU’s most powerful foreign policy tools, and it can play a major role in stabilising the accession countries and helping their economies grow by promoting reforms and attracting investment. Additionally, enlarging the EU would provide the Union with additional market size, natural resources and geopolitical heft (particularly if Ukraine joined).

While many EU leaders have argued that enlargement is urgent, especially in relation to Ukraine, the reality has often not lived up to the rhetoric. Ukraine and Moldova started accession negotiations last year, joining Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia. Meanwhile, the start of Georgia’s negotiations has been put on hold due to concerns over the rule of law on the EU’s side, compounded by Georgia’s own loss of interest after the Georgian Dream party consolidated its hold on power in the disputed October 2024 elections. As for Türkiye, it is hardly ever mentioned by the Commission as a candidate country, despite having held that status since the early 2000s. Its accession bid has been frozen since 2018 due to a range of bilateral disagreements with the EU.4 The opening of negotiations with Bosnia-Herzegovina is subject to a range of conditions which the dysfunctional state cannot meet, and Kosovo is only a potential candidate, with five member-states not recognising it as a sovereign state.

The start of negotiations with Moldova and Ukraine is an important step. Ukraine has made great efforts despite being under attack, for example in strengthening its judiciary. However, the EU assesses its preparation for membership as limited, with Kyiv having had little time to build up a track record in implementing reforms. Similarly, Moldova has made some progress but continues to suffer from a range of challenges, for example lack of administrative capacity to implement EU law. In the Western Balkans, Montenegro is more advanced and can start working towards closing negotiating chapters. However, challenges remain in terms of implementing reforms and making the justice system more efficient. In Albania, corruption, political interference in the judiciary and freedom of expression are serious concerns. In North Macedonia, the rule of law remains a challenge, with the EU calling attention to judicial independence and the need to fight corruption. Finally, Serbia has suffered from democratic backsliding over the last 10 years and has major shortcomings in the rule of law.

Aside from obstacles stemming from within the candidate countries, the pace of accession is slowed by politics on the EU side. EU leaders have always insisted that enlargement will depend on the EU’s readiness for it. The October 2023 Grenada Declaration mentions the need for the EU to “lay the necessary internal groundwork and reforms” for enlargement.5 However, the European Commission states that “no consensus has been found on how best to approach this issue”.6 Many leaders insist on the need to reform the EU’s voting rules to reduce the potential for individual member-states to paralyse the Union with vetoes – including on foreign policy. But many member-states are unwilling to drop their veto. Reforms to the EU budget are also often discussed as a pre-requisite to enlargement, but their form remains contentious.

To prevent disillusionment in the enlargement process, the EU has recently embraced the notion of gradual enlargement.

Opinion polling suggests that most European citizens favour enlargement.7 Still, those that oppose enlargement outnumber its proponents in several member-states, including Austria (59 per cent vs 35); Czechia (53 per cent vs 42); France (54 per cent vs 37); Germany (51 per cent vs 44); and Luxembourg (55 per cent vs 41). Many politicians, in particular from populist parties, are leaning on fears of enlargement to gain votes. But opposition by specific interest groups, such as farmers, has also forced mainstream politicians – especially in Poland – to take a tough line on the access of Ukrainian agricultural produce to the EU market.8

Internal EU difficulties, combined with the hurdles faced by accession candidates, led to the freezing of Türkiye’s accession process, and to disillusionment with the enlargement process in many Western Balkans countries. To reverse this disillusionment in the Western Balkans and to prevent Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova from suffering the same fate, the EU has recently embraced the notion of gradual enlargement.9

The idea is that, as candidate countries adopt the acquis, they would be eligible for more funding from the EU budget and be integrated into individual policy areas in the single market. Their citizens may have the right to work in the EU for lengthy periods or potentially without limits. Leaders from the candidate countries could regularly participate in informal meetings of EU leaders and potentially also in some sessions of formal EU summits. By gaining tangible benefits immediately, the candidate countries would have short-term targets to work towards and could more easily maintain domestic political support for enlargement. Meanwhile, member-states and citizens that are sceptical of enlargement would see that candidates are able to reform effectively, and their opposition would diminish.

The EU’s 2023 ‘new growth plan for the Western Balkans’ contains some ideas for what phased enlargement could look like. For example, after aligning with the relevant areas of EU law, the candidates could conclude agreements on conformity assessment to make it easier for their products to enter the EU market. The Commission also suggests improving customs co-operation to reduce checks and waiting times at borders, including the candidates in the Euro’s single payments area, and recognising certain professional qualifications.10

To integrate a candidate country into individual areas of the single market, the EU needs to trust it to apply regulations (for example on consumer safety) comprehensively and effectively, in compliance with ECJ jurisprudence.11 Therefore, even gradual integration depends on candidate countries adopting EU law and having the administrative capacity to implement it in a manner that the EU trusts. Ultimately then, gradual integration depends on whether leaders in candidate countries are willing to undertake politically and economically difficult reforms, and on the degree of support that the EU can offer them to mitigate the effects of opening their markets to direct competition from EU firms.

What associate membership could look like

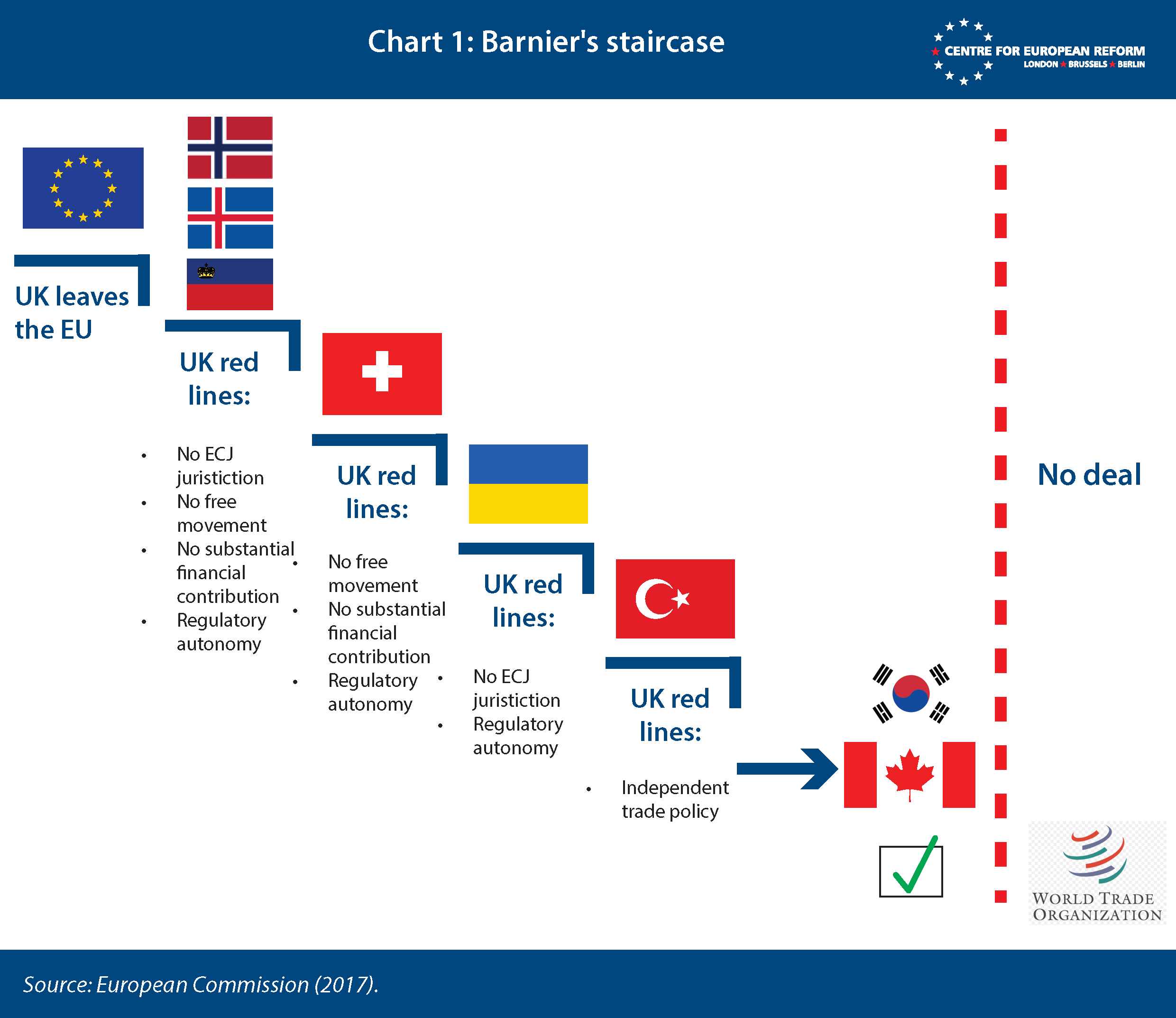

The EU’s increasing emphasis on gradual accession is likely to prompt additional thinking from the EU on how non-members can be involved in individual areas of EU policy. Over time, that might lead the EU to develop a more structured associate membership status - with potentially significant consequences for the EU-UK relationship. Defining what associate membership of the EU could entail is not an easy task. It is worth quickly taking stock of the EU’s relationships with key partners. The ‘staircase’ developed by the EU’s negotiator Michel Barnier during the Brexit negotiations (Figure 1) remains a useful guide to what the main points in determining a country’s relationship to the EU are.

Barnier’s model, while simplified, focuses on the key elements in determining the relationship with the EU: the degree of oversight by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), financial contributions to the EU budget, regulatory autonomy, freedom of movement, and an independent trade policy. As the model illustrates, of all non-members, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein (the non-EU members of the European economic area (EEA) have the deepest integration with the EU. They are de facto full members of the single market, except for some carve outs in agriculture and fisheries. EEA members also have some limited decision-shaping rights in the form of participation in technical meetings to prepare EU regulations. They dynamically align with EU law and with rulings of the ECJ. This is not done by applying EU law directly, but rather by transposing EU law into a body of EEA-law that mirrors it. The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) court has jurisdiction over EEA law, but mirrors the ECJ’s jurisprudence. The EFTA Surveillance Authority monitors implementation of EEA law in non-EU EAA countries, mirroring the Commission’s responsibilities in this respect for the EU. EEA members implement free movement for EU citizens, and make contributions to the EU budget.12 Norway is formally associated to the EU’s defence instruments, and its defence firms can work closely with their EU counterparts. EEA members are not members of the EU customs union, and are free to make their own free trade agreements with third countries.

Switzerland has a close level of integration with the EU. Switzerland’s relationship to the single market is underpinned by over a hundred bilateral agreements overseen by dozens of joint committees, leading to a complicated governance patchwork.13 Switzerland implements free movement for EU citizens and is not in a customs union with the EU. Switzerland does not automatically follow EU law, leading to lengthy negotiations whenever EU law changes. That has led to dissatisfaction, in particular on the EU side. The EU and Switzerland have therefore negotiated a new package of agreements that will ensure dynamic alignment with many aspects of EU law, such as product regulation and food safety.14 Switzerland does not have substantial defence co-operation with the EU.

After Brexit, Britain defined its red lines as no to the single market, customs union and free movement.

The Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) that the EU has with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova represent a significantly lower level of integration. These agreements are not based on dynamic alignment. Instead, they rely on legislative approximation of EU law, a looser system of alignment in which countries adapt their legislation to produce the same effect as EU law without any binding commitment to harmonise rules. The degree of increased market access depends on the degree of alignment with EU law. In theory, once the process of legal approximation is complete, DCFTAs can lead to EEA-like levels of market access. The agreements are overseen by arbitration panels that, in the case of dispute, will request binding judgements from the ECJ.15

Ukraine is unique among the EU’s DCFTA partners in that it is also being progressively integrated into EU defence industrial instruments. For example, the proposed European Defence Industry Programme would allow for Ukraine’s participation, as would the loans provided by the proposed Security Action for Europe (SAFE) Regulation. The EU Defence White Paper, released in March 2025, sees Ukraine’s integration into the EU’s defence industrial base as a key aim.16

Türkiye’s relationship with the EU does not fit into any of the previous models. Türkiye is unique among the EU’s close partners in that it is in a customs union with the EU for manufactured goods. As a result, trade in this sector is relatively smooth. However, Ankara’s relationship to the single market and the EU acquis is looser than that of other EU neighbours, and the level of market access is also lower. In terms of defence co-operation, the EU sees Türkiye as a third country, and Turkish defence firms face barriers in accessing EU instruments.

The UK’s relationship to the EU, as set out in the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) is the most distant of all the cases considered. Soon after Brexit, the British government defined its red lines as no to the single market, no to the customs union and no to free movement. That necessarily meant accepting a lower level of market access than the EEA countries or Switzerland, and more trade friction than Türkiye. At the same time, the UK chose not to include foreign policy and defence in the TCA. Similar to Türkiye, the UK is seen as a third country as far as EU defence tools are concerned.17

In theory, Associate status could encompass a large range of possible relationships with the EU, from rather distant to very deeply integrated.

At the most deeply integrated level, associate membership could be a sort of EEA+, similar to the associate membership model envisaged in the report by the Franco-German group of experts, which centres of single market participation.18 Associate countries could be de facto full members of the single market, with some decision-shaping rights. In return, they would dynamically align with EU law and ECJ rulings, sign up to free movement and perhaps also be in a customs union with the EU. Associate members would contribute to EU programs in proportion to their GDP, and potentially be eligible for funding from EU programs such as cohesion funds. Defence co-operation could be a key component of co-operation between the EU and associate members. Associate members could be formally associated with the EU’s defence tools, and their firms could participate in EU-funded programs on a similar footing to their EU counterparts.

Associate EU membership could conceivably describe a range of different, tailored relationships between the EU and its partners.

Unlike EEA members, members of the EEA+ would be extensively involved in consultations with EU bodies. Leaders of associate members would attend EU ministerial and leaders’ meetings with speaking rights but without voting, and their officials would be involved in working groups – allowing them to influence regulation. It is almost impossible to imagine that associate membership would have a higher level of integration, because giving associate members voting rights would make them to all effects EU members.

Alternatively, associate membership could entail a much more limited level of integration. In economic terms, associate countries could have a more distant relationship to the single market, only fully aligning with EU law in some economic sectors. For example, associate members could have a close relationship to the single market in some areas (like manufactured goods) and not others (digital services). They would not have decision-shaping rights and might or might not be part of the customs union and have free movement. Associate members could still be closely integrated into EU defence industrial tools and other areas of EU defence co-operation – as the EU plans to do with Ukraine. Leaders of associate members would attend Foreign Affairs Council meetings, some European Council meetings and Council meetings in policy areas in which they have fully adopted the EU acquis. It is difficult to envisage an associate membership with a significantly lower level of integration than set out above. If it only involved close political dialogue, the EU would be unlikely to label it as associate membership.

Associate membership could also be an intermediate status on the road to membership along the lines of the ‘staged accession’ model developed by CEPS and CEP.19 According to this four-stage model, a candidate would become an associate member once it had progressed substantially towards membership. That would give it the right to half the funding it would have as an EU member and some involvement in policy development. As a candidate country makes further progress in implementing the acquis it would move to a second stage, gaining the right to more funding and greater participation in EU institutions, in the form of speaking rights in the Parliament and Council. In a third stage, the associate member would transition to partial EU membership, becoming a ‘new member-state’. As such it would have right to full EU funding and participation in EU politics. However, it would not have a member on the Commission and, while it would have voting rights, it would not have veto powers in the Council. The final stage of accession would see the ‘new member-state’ become an ordinary member-state and gain the same rights as all other members.

Ultimately, associate EU membership could fall somewhere in between any of the above options. It could conceivably be a term that describes a range of different, tailored relationships between the EU and its partners. But the basis of all such relationships would have two pillars: a significant level of sectorial single market integration and an intense degree of political dialogue, at the working level, at leaders’ level and between members of parliament.

The EEA+ model could appeal to countries that want to be part of the EU and are technically ready to join but cannot, whether because of their own internal domestic politics or because there is no consensus among EU members on their accession. Such countries could probably accept EEA+ status, seeing it either as a destination in its own right or as a necessary stepping-stone to membership. For the EU itself, the advantage would be that of politically and economically anchoring countries in its orbit even without membership, minimising the risk of backsliding.

The minimalist model of associate membership could appeal to a broader range of countries. For example, it may appeal to candidate countries that do not want to progress further towards membership or to countries that want a moderately close relationship with the EU but do not want to pursue membership. The minimalist model could also work for countries that find their path to the EU blocked by opposition on the EU side, if they accept associate membership as an intermediate status. For the EU, the appeal of the minimalist model could also be substantial. The EU would gain significant benefits, tying partner countries more closely both politically and economically. At the same time, the EU would not have to give a partner full market access in all sectors – which could be useful to protect certain economic sectors and voting constituencies. The EU would also not have to grant a partner the same level of funding that it would be entitled to as a member. The EU would also be able to avoid giving the associate member free movement for its citizens – which is often a big source of public opposition to EU enlargement. In essence, the main appeal for the EU would be that it would gain some of the benefits of enlargement, while having to undertake fewer compromises.

Will the EU develop an associate membership model? Currently, a large obstacle to such a model developing is that the candidate countries are sensitive about being offered something that is not full membership or that relegates them to a second tier. There would also be a risk that the existence of such a model would sap reform momentum and discourage the candidate countries. Nevertheless, associate membership may still develop, as it addresses real issues and offers tangible benefits to both the EU and the candidates. The key variable will be whether associate status is seen as worthy in its own right, and whether it is seen as a possible stepping stone to membership or not.

Implications for the EU-UK relationship

The implications for the UK of the EU developing an associate membership status would depend on what that status entailed in practice, and on how the EU and the UK perceived it.

The UK is seen as a third country as far as EU defence instruments are concerned.

The EU-UK trade relationship has been shaped by many factors on both sides. On the UK side, the key factors have been the rejection of free movement to reduce immigration, the desire for an independent trade policy to strike free trade deals, and the wish to maintain a high degree of regulatory autonomy. These red lines, established by Conservative governments in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum, have proven remarkably entrenched. The current Labour government has embarked on a ‘reset’ with the EU, aiming to deepen both economic and security co-operation. On the security side, the UK has shown its willingness to engage in deep co-operation with the EU, including on matters relating to the defence industry. Conversely, the UK’s economic red lines on the single market, the customs union and free movement have not shifted. However, the new government has shown it is open to aligning with the EU in individual economic sectors, such as sanitary and phytosanitary regulation. The UK’s approach may shift further if the economic turbulence from US President Donald Trump’s highly protectionist approach to trade pushes the UK to revise some of its red lines and attempt to align more closely with the EU.

On the EU side, the key consideration shaping negotiations with the UK has been the wish to maintain the EU’s legal order and to prevent any British ‘cherry-picking’. In practice this has meant that the EU has been less flexible in its relationship with the UK than in its relations with other partners, especially on the question of whether sectoral dynamic alignment is feasible. This stance has, until recently, extended to security and defence co-operation with the UK. Despite the close level of integration between the UK and the EU defence industrial bases, the UK is considered a third country as far as EU defence instruments are concerned, and British firms cannot meaningfully participate in EU instruments.20 More recently, the EU seems to be growing more open to working with the UK. The proposed SAFE regulation paves the way for closer UK involvement in EU defence initiatives: if the UK negotiates a security and defence partnership with the EU, there can then be case-by-case co-operation on SAFE-funded actions. The EU and the UK are currently in the process of negotiating such a partnership. However, progress has been slow, because security and defence talks have been folded into the broader reset negotiations, and these are only progressing at the speed of the most contentious economic issues.21

Applying the EEA+ model of associate membership to the UK is likely to meet little opposition on the EU side, as it involves few compromises by the EU. However, the EEA+ model is unlikely to appeal to the UK as long as its red lines remain those of rejecting the single market, free movement, and the customs union. Of course, it is possible that the UK government will revise its current red lines. But if that happens, fully re-joining the EU may seem like a more tempting option than the EEA+ option, as re-joining would allow the UK to be fully engaged in making EU law. The key variable would be whether the EU was willing to grant the UK full membership, or whether member-states would insist that the UK becomes an associate member for a specified period of time as a sort of ‘cooling off period’. In that case, the EEA+ model could be a very useful docking point for the EU and the UK, at least for some time.

If the associate membership model developed by the EU was closer to the minimalist model discussed above, the implications for the EU-UK relationship are likely to be significant. In developing such a model, the EU would show that free movement is not a precondition for enhanced integration with the single market, and that it is possible for partners to have partial integration into the single market in exchange for dynamic alignment with EU law and acceptance of ECJ jurisdiction in some sectors – without free movement. This is likely to be very appealing for the UK, because opposition to immigration remains the biggest blockage to a closer relationship on the UK side, and because sectoral alignment would be easier for the British government to accept than alignment in all areas of the single market. However, the EU’s willingness to offer the UK such a model would depend on whether member-states and the Commission remain concerned about ‘cherry-picking’ or whether the development of a greater variety of relationships with non-EU partners eases those fears. Much would also depend on the state of bilateral relations with the UK, and on whether tensions with the US prompt the EU to be more open to exploring new arrangements to deepen economic co-operation with the UK.

Even if the EU does not develop a fully-fledged associate membership model, EU-UK defence co-operation could deepen if the EU continues to develop defence co-operation with candidate countries, and Ukraine in particular. As set out in a recent CER paper, it is possible to envisage several different models of UK association to EU defence instruments.22 The more defence is seen as a self-contained area of co-operation between the EU and its partners, and insulated from bilateral economic issues, the greater the prospects for UK-EU co-operation.

Conclusions

The renewed momentum for enlargement in the wake of Russia’s war on Ukraine is pushing the EU to think creatively about how to work more closely with accession countries. The EU is increasingly embracing the notion of phased enlargement, premised on the notion that the candidate countries can be integrated more closely in the EU already before accession. At the same time, the EU is exploring new ways of working with candidate countries in defence, especially with Ukraine’s planned integration in the EU’s defence industrial toolbox.

These developments could have a significant impact on the EU-UK relationship. Over time, phased enlargement may lead the EU to think more flexibly about relations with neighbours, and to develop formal association models for countries that do not want to or cannot become full members.

Depending on what associate membership of the EU looked like in practice, the implications for the EU-UK relationship could be significant. The UK could end up as an associate member during a hypothetical process to re-join the EU. Alternatively, the EU and the UK could draw inspiration from associate membership to rethink and deepen their relations. Even if the EU does not develop a fully-fledged associate membership model, the scope for closer defence co-operation with the UK could grow significantly if the EU continues to strengthen defence co-operation with accession candidates and defence is increasingly seen as unique, and separate from the trading relationship.

2: Zselyke Csaky, ‘Enlargement and the rule of law: Diverging realities’, Centre for European Reform insight, November 27th 2024.

3: Council of the European Union, ‘Conclusions on Enlargement’, December 17th 2024.

4: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘The EU and Türkiye: A relationship adrift’, Centre for European Reform insight, October 21st 2024.

5: European Council, ‘The Grenada Declaration’, October 6th 2023.

6: European Commission, ‘Communication from the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council on pre-enlargement reforms and policy reviews’, March 20th 2024.

7: Eurobarometer Winter 2024.

8: Reuters, ‘Polish farmers block border crossing with Ukraine in Mercosur trade protest, PAP reports’, November 23rd 2024.

9: European Council, ‘Conclusions’, June 24th 2022; Council of the European Union, ‘Council conclusions on Enlargement’, December 12th 2023.

10: European Commission, ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Comittee and the Committee of the Regions: New growth plan for the Western Balkans’, November 8th 2023.

11: European Commission, ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council on pre-enlargement reforms and policy reviews’, March 20th 2024.

12: Aslak Berg, ‘Should the UK pursue dynamic alignment?’, Centre for European Reform insight, July 4th 2024.

13: European Commission, ‘EU-Swiss relations factsheet’, September 25th 2016.

14: Anton Spisak, ’The new EU-Swiss deal: What it means and the lessons it holds for the UK-EU ‘reset’’, Centre for European Reform, March 17th 2025.

15: Beth Oppenheim, ‘The Ukraine model for Brexit: Is dissociation just like association?’, Centre for European Reform insight, February 28th 2018.

16: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘One step forward for Europe’s defence’ Centre for European Reform insight, March 26th 2025.

17: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘How the EU and the UK can deepen defence co-operation’, Centre for European Reform policy brief, March 7th 2025.

18: Report of the Franco-German Working Group on EU institutional reform, ‘Sailing on high seas: reforming and enlarging the EU for the 21st century’, September 18th 2023.

19: Michael Emerson, Milena Lazarević, Steven Blockmans, Strahinja Subotić, ‘A Template for Staged Accession to the EU’, Centre for European Policy Studies and European Policy Centre (Belgrade), October 1st 2021.

20: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘How the EU and the UK can deepen defence co-operation’, Centre for European Reform policy brief, March 7th 2025.

21: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘One step forward for Europe’s defence’ Centre for European Reform insight, March 26th 2025.

22: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘How the EU and the UK can deepen defence co-operation’, Centre for European Reform policy brief, March 7th 2025.

Luigi Scazzieri is a non-resident associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform

April 2025

View press release

Download full publication

This policy brief is the first of a three-paper CER/KAS project, ‘Navigating stormy waters: UK-EU co-operation in a shifting global landscape.’ The second brief focuses on UK and EU approaches towards China. The final paper looks at the EU-UK reset, a year after its start.