Towards an EU 'defence union'?

- The need for Europeans to urgently strengthen their defences is clearer than ever. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has pushed European countries to raise their defence budgets significantly. But Europeans face three big obstacles. First, the capability gaps to fill remain very large. Second, national procurement and capability development plans are quite fragmented. Third, the European defence manufacturing is undersized and largely organised along national lines.

- This policy brief takes stock of the EU’s involvement in defence, its challenges and its prospects. The Union has emerged as a significant defence actor in recent years: it has tools to help expand defence production, to foster joint research and development and to promote joint procurement. There are plans to scale these instruments up, and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen talks of establishing a ‘defence union’.

- One issue with the EU’s efforts is limited funding: EU instruments are small and finding new resources is not easy. Another challenge is the design of EU instruments, particularly when it comes to striking the right balance between urgent military kit needs and long-term industrial strengthening. This in turn is closely linked to whether the EU’s tools are closed to partners like the US and the UK.

- The biggest challenge of all may be navigating the politics of the EU’s involvement in defence. Washington has been sceptical of EU defence efforts under President Biden and is likely to be even more so under Trump. US opposition makes many EU states cautious about the Union’s defence initiatives. Some member-states are also sceptical of the European Commission becoming more deeply involved in defence. Finally, the political economy of European defence is tricky, not least as most of Europe’s defence industry is in its western member-states.

- The prospects of EU involvement in defence will depend on how the Union approaches these challenges. The EU should explore the possibility of channelling more funds from its budget to defence, and ensure that more private and national public finance can flow into defence. The EU should also consider grant-funding to finance efforts by single member-states that benefit European security more broadly. Defence bonds, issued by the EU or by some member-states, may be an option.

- The negotiations for the next EU budget will be a key test. Current levels of funding would not lead to major changes. Conversely, if the EU establishes a budget in the region of €10 billion a year for defence, that would steer national procurement decisions towards co-operative solutions, and over time could reshape both national planning and the industry.

- The EU’s initiatives are more likely to be successful if they are sharply focused on addressing military needs and if they add real value to member-states’ national efforts. The EU should focus on those capabilities that are military priorities and that are broadly shared by the member-states. Improving European air and missile defences would be a promising starting point.

- Member-states’ scepticism about giving the Commission more powers in defence will probably throttle its ambitions to bring about a defence single market through regulation, or to move towards more EU-level defence planning. However, more co-ordinated planning and something closer to a single market for defence can emerge organically over time if both member-states and industry see co-operation as a rational decision. The EU should focus on providing incentives in that direction.

- If EU countries continue to buy from non-EU providers in large quantities, then the European defence industry will remain undersized. At the same time, a restrictive approach to partners risks disrupting existing co-operation between EU countries and non-EU partners. It also means that the EU will miss out on the additional funds and synergies that working with allies can bring. Instead of its current blanket approach, the EU would be better served by taking a case-by-case approach to the involvement of partners in its projects.

- Defence considerations should be mainstreamed into policy-making, to ensure that the impact on defence is taken into account by lawmakers legislating on other issues, such as the green transition, critical raw materials and resilience.

- Europeans have avoided taking their defences seriously since the end of the Cold War, but they can no longer afford to do so. The EU has the potential to play a substantial role in addressing these challenges, in synergy with NATO and national efforts, if it adopts an open, pragmatic approach, sharply focused on military needs.

Europeans need to bolster their security. Even if the conflict in Ukraine were to end soon, the threat to European security from Russia would remain. Europe’s southern neighbourhood is a source of threats, both from state and non-state actors. And in Donald Trump’s second term, America is likely to devote fewer resources to defending its European allies – even if Trump’s transactional rhetoric towards Europe suggests it is unlikely to abandon them entirely.

Advancing European defence co-operation is a priority for Ursula von der Leyen in her second term as Commission president. She often talks of establishing a ‘defence union’, and has entrusted the task of advancing the project to the EU’s first dedicated defence commissioner, former Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius. Kubilius, together with the new High Representative, former Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, is preparing a ‘white paper’ on European defence, due in mid-March. The aim of the paper is “to frame a new approach to defence and identify investment needs to deliver full spectrum defence capabilities based on joint investments, readying the EU and member-states for the most extreme military contingencies”.1 The white paper will follow three other recent EU reports that referred extensively to the EU’s role in defence: those of former Italian prime ministers Mario Draghi (on competitiveness) and Enrico Letta (on the single market), and that of former Finnish president Sauli Niinistö on preparedness and readiness. The three reports all highlighted the fragmented nature of Europe’s defence industry and called for Europeans to strengthen their defence capabilities.

The EU has the potential to play a substantial role in building up Europe’s defences. The Union has emerged as a significant defence actor in recent years, with tools such as the European Defence Fund (EDF) that foster more joint research and development. In theory, the Union could emerge as a facilitator of Europe’s efforts to strengthen its defences. However, that outcome is by no means guaranteed, as significant obstacles may keep the EU’s role in defence more circumscribed even as co-operation between European countries deepens bilaterally or in small groups. This paper starts by mapping out Europe’s defence challenge and the current state of its efforts to become more self-reliant. It then looks at the EU’s different initiatives in defence and their prospects. Finally, it makes recommendations for how the EU can maximise the impact of its efforts.

Europe’s defence challenge

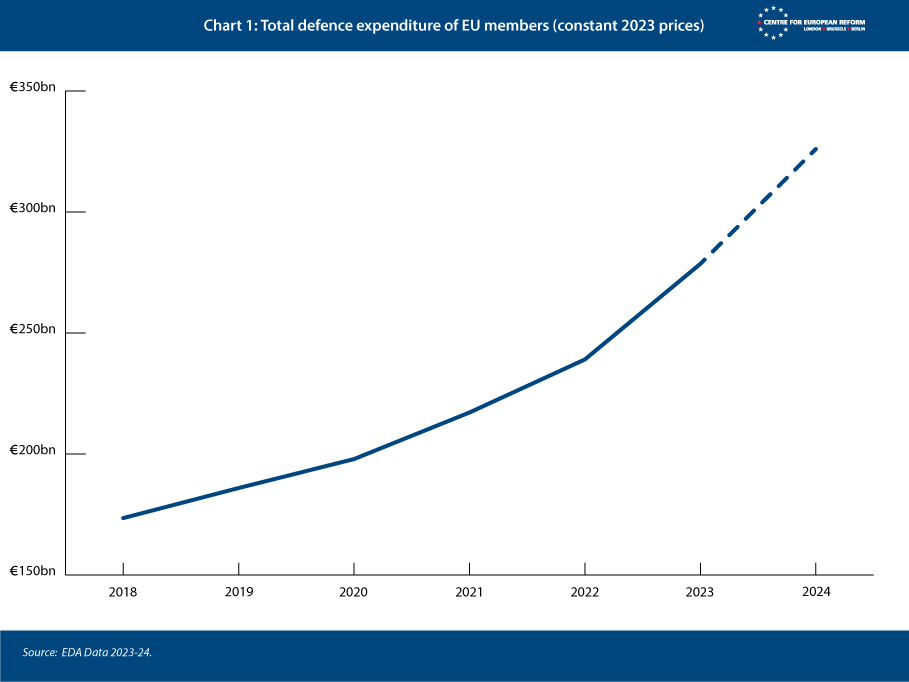

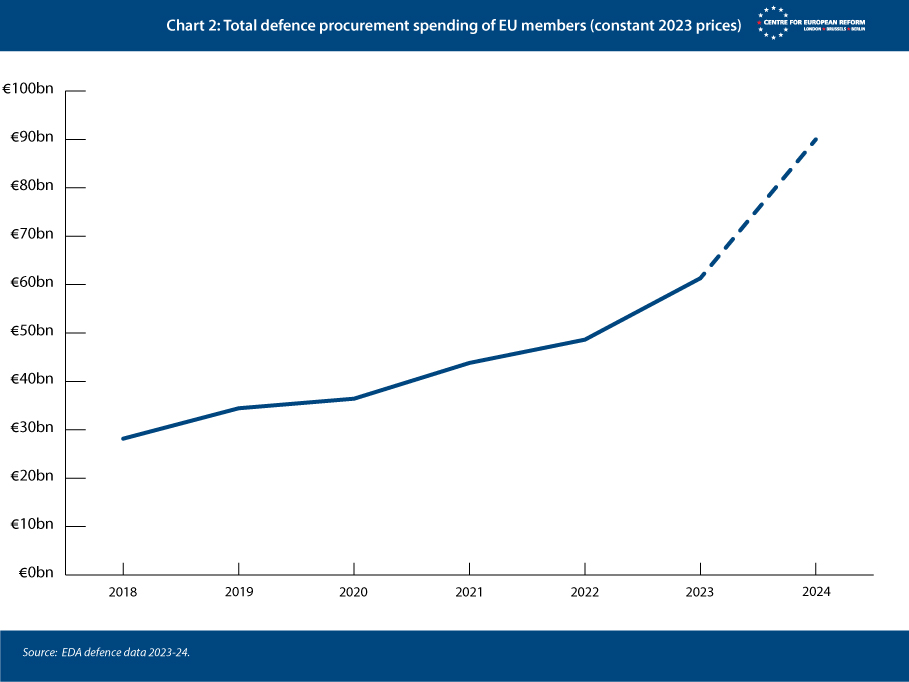

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has pushed Europeans to increase defence spending. National defence budgets have substantially increased across most member-states. According to NATO data, 16 EU members of NATO were set to spend a sizeable 2 per cent of GDP on defence in 2024. Notably, Germany, which has long been a defence laggard, is now spending 2 per cent – which has made Berlin Europe’s largest defence spender by a significant margin. According to the latest data by the European Defence Agency (EDA), EU states’ defence expenditure stood at €279 billion in 2023 and, according to preliminary estimates, was set to hit €326 billion in 2024, amounting to 1.9 per cent of GDP – a 79 per cent real-terms increase since 2014 (Chart 1). Meanwhile, real-term spending on procuring equipment has risen from just over €40 billion in 2020 to around €60 billion in 2023 and is set to hit over €90 billion in 2024 (Chart 2).2

However, Europe faces three big issues in building up its defence capacity. The first is that the gap to fill remains very large. European countries cut defence spending after the end of the Cold War, and budgets fell further following the financial crisis of 2008-09. According to the European Commission, if spending had been maintained at 2008 levels, EU countries would have spent an additional €160 billion by 2018. And if all EU members had spent 2 per cent on defence, that would have resulted in an additional outlay of €1.1 trillion between 2006 and 2020.3

Europeans have made moderate headway in repairing some of their past under-investment.

Europeans focused their smaller budgets on expeditionary operations, neglecting the equipment, stockpiles and readiness efforts needed for high-intensity conflict. Important military capabilities were scrapped, atrophied or were never acquired. For Europeans, it proved more convenient to rely on the US to provide numbers and key ‘enablers’, in areas such as air defence, ballistic missile defence, intelligence and heavy air transport. Europeans have made moderate headway in repairing some of their past under-investment, but the goalposts have moved, given Russia’s improved capabilities and the fact that US support cannot be fully counted on. Moreover, the threat of conflict means that more funding needs to be directed to maintaining a larger share of military forces at a high level of readiness. All this means that having capable armed forces with the necessary preparedness and resilience in terms of reserves will take many years. Realistically, Europeans will need to spend 3 per cent or more on defence.

The second problem Europeans face is a fragmentation of national planning and procurement efforts. While both NATO and the EU have defence planning processes, there is no effective mechanism to force different countries to co-ordinate better and agree on what equipment to buy in an efficient manner, ideally through co-ordinated or joint purchases. Countries make procurement decisions largely on their own, without prioritising co-operation, but rather other considerations such as price, specific requirements or a workshare for domestic industry. As a result, co-operative R&D and co-operative procurement spending remains low. According to the EDA, last year there was a “temporary slowdown of collaborative procurement”, and only 6 per cent of R&D spending was collaborative.4 European armies operate a plethora of different types of equipment – although the picture is not quite as bleak as it looks when one excludes legacy kit.5 European armed forces thus miss out on savings from economies of scale in procurement and maintenance, and are not as capable as the headline spending figures suggest. Duplicated systems that are not interoperable create unnecessary costs and hinder collaborative efforts.

Co-operation on research and procurement is challenging: all countries need to agree on the specific requirements of a piece of equipment, concur on a division of work between their industries, and trust each other not to pull out of a project. Even national procurement is not immune to delays and spiralling costs, but many co-operative projects have suffered from serious challenges in these respects. For example, in recent years, the Franco-German projects for a next-generation aircraft, the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), and for a main ground combat system (MGCS) have been marred by disagreements leading to long delays. It is unclear whether either project will come to fruition.

An undersized fragmented defence industry means that production times are long and unit costs high.

The third problem relates to the size and organisation of the European defence industry. After the end of the Cold War, manufacturing shrank along with national budgets, as the sector adapted to producing less equipment. As a result, it struggled to ramp up production in the wake of Russia’s invasion. The fragmentation of spending by European countries also means that Europe’s defence industry is largely organised along national lines. There was a wave of industrial consolidation in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the aerospace and missile sectors, but this has not been repeated in other areas. As the defence gap analysis produced for EU leaders in March 2022 states, the EU’s defence industrial base is characterised by “a number of national players operating in small markets, producing therefore small volumes.”6

An undersized and fragmented defence industry means that production times are long, and unit costs are often high. Governments have also been reticent to place long-term orders. Difficulties in scaling up production explain why the EU struggled to provide Ukraine with the 1 million rounds of artillery ammunition that it had promised to deliver in March 2023. The EU had promised to hit the target within a year, but it took the Union until November 2024 to fulfil its pledge.7

Defence experts have long known about the effects of defence-industrial fragmentation, but the Draghi report drew more attention to them. The result is that – together with the wish to strengthen political relationships with Washington – many European countries buy defence kit in large quantities from the US. For example, much of Germany’s €100 billion special fund announced in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion has gone to the purchase of American F35 fighters. Meanwhile, Poland’s desire to obtain equipment quickly meant that it splurged cash on readily available South Korean equipment.

According to EU figures, between 2007 and 2016, member-states spent over 60 per cent of their procurement budgets on non-EU equipment.8 Meanwhile, according to figures cited in the Draghi report, in the year between June 2022 and June 2023, 78 per cent of EU member-states’ procurement went to non-EU suppliers, with 63 per cent of that accounted for by the US. These figures are contested, with a study by the International Institute for Strategic Studies pointing to a lower share of non-EU procurement.9 However, the two studies are not directly comparable as the IISS study includes non-EU European NATO members, and is based on a different timeframe. What is clear is that Europeans buy defence equipment from abroad in large quantities. Unless more orders flow to the European defence industry, the pattern is likely to continue, as European production capacity will remain constrained and there will continue to be incentives for member-states to buy off-the-shelf from others.

For Europeans to strengthen their defence capacity, they need to address all three of these issues, and increase the readiness of their military forces. European efforts to improve military capabilities are playing out in a range of institutional frameworks: national, NATO, small groups and EU. The national line of effort is still the backbone of defence. Countries have national defence budgets and national troop formations. National procurement, whether from domestic industry or from foreign producers, is still the main way of buying military equipment. NATO plays an essential role: it sets standards and drafts plans setting out what each ally should do in a crisis; and its defence planning process is the most important framework for deciding what military assets the alliance as a whole needs, and what each ally needs to contribute. NATO has also recently started to play a role in funding defence innovation, through the NATO Innovation Fund and the Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic. Finally, NATO helps allies identify opportunities for co-operation in acquiring military equipment, and has a structure to facilitate joint acquisition and logistics in the form of the NATO Support and Procurement Agency. However, NATO lacks financial instruments to encourage allies to increase defence production or procure equipment together.

Aside from national efforts and NATO, small group co-operation frameworks are very important. Some countries have integrated their military forces so they can operate seamlessly together: for example the Dutch and German land forces or the Belgian and Dutch navies.10 This also applies to procurement, with two or more countries acquiring military equipment co-operatively. Recent examples include the joint order for 1000 Patriot missiles placed by Germany, the Netherlands, Romania and Spain in January last year, or the joint order placed by seven member-states for 155mm ammunition through the EDA in October 2023.11 Finally, the organisation for Joint Armament Co-operation (OCCAR), which has Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom as members, often plays a pivotal role in managing large co-operative procurement programs, such as the A400M air transport.

Understanding the EU’s role in defence

The EU’s involvement in defence has three pillars. The first is operational, and involves EU missions and assistance to partners like Ukraine. The second pillar encompasses the EU’s efforts to strengthen its defence industrial base and to foster more co-operation between the member-states. And the third pillar concerns the EU’s efforts to address non-military threats such as cyberthreats.

The EU has used the European Peace Facility to provide Ukraine with €6.1 billion in military assistance.

The EU’s operational role

Since creating what is now the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in the late 1990s, the EU has launched over 40 CSDP operations. These have focused on a range of tasks like training partners’ security forces, securing shipping lanes from piracy and peacekeeping. Perhaps the best-known recent example is the mission to train Ukrainian troops, set up in 2022. It had trained 63,000 soldiers by November last year, with an additional 15,000 due to finish training in the first few months of 2025.12

In theory the EU has so-called battlegroups on standby, with troops provided by member-states on a rotational basis. But these have never been used. Deploying the battlegroups requires consensus, and this has never been secured, largely because member-states have historically proved unwilling to contribute troops to potential EU operations. Moreover, the Union does not have the ability to carry out significant combat operations, because its command-and-control capabilities are limited. In 2022, member-states agreed to revamp the battlegroups into a larger formation of around 5,000 personnel called the Rapid Deployment Capacity (RDC), and to strengthen the EU’s ability to plan and command large-scale missions. However, it is unclear whether such plans can be fully implemented for the foreseeable future. Resourcing the RDC is a much lower priority for member-states than allocating scarce forces and staff to NATO structures.

The European Peace Facility (EPF) can also be seen as an operational tool. The facility is an off-budget fund established in 2021 to fund assistance to partners globally. The EU has used this to provide Ukraine with €6.1 billion in military assistance (with another €5 billion, in a dedicated Ukraine envelope, available for use). The EPF has been used to partly reimburse member-states for the equipment they have given to Ukraine. The EPF was also used to finance joint procurement on Ukraine’s behalf. In May 2023, EU leaders decided they would use €1 billion from the EPF to procure 1 million 155mm shells for Ukraine from the EU defence industry.13 The EPF, which was worth €5.7 billion at the start of the conflict, has been repeatedly topped up by the member-states and is now worth €17 billion overall.

The EU’s efforts to improve defence capabilities

The second dimension of the EU’s involvement in defence relates to fostering co-operation in defence capabilities. Unlike other goods, there is no EU single market for defence products. Article 346 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) carves out an exemption for essential national security interests, stating that a member-state can “take such measures as it considers necessary for the protection of the essential interests of its security which are connected with the production of or trade in arms, munitions and war material”. The reason for such a carve-out is that countries consider their defence choices a matter of national security. And countries want to ensure that they can give their domestic defence industry enough work to survive. The Commission has tried to push member-states to open up defence procurement and to ease transfers of defence equipment between them: in 2009 it adopted two directives that aimed respectively to push member-states to open more national tenders to external competition, and to simplify the rules on transferring defence equipment across EU borders. However, these have had little effect: a report by the European Parliament committee on the internal market and consumer protection found that member-states were making extensive use of Article 346 to avoid publishing open tenders, and that many administrative hurdles made cross-border transfers challenging.14

The EU’s role in improving defence capabilities has deepened since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

In the mid-2010s, the EU shifted to providing member-states and their defence industries with incentives to work together. The EU had been a player in defence-related research since 2004 though its R&D programmes. In 2017, the EU established a Preparatory Action for Defence Research, worth €90 million over two years, to foster joint research. In 2019, this was complemented by a European Defence Industrial Development Programme, worth €500 million over two years and meant to finance co-operative development efforts. After long negotiations, in 2021 the EU established the much larger European Defence Fund (EDF), worth almost €8 billion in the current EU 7-year budget, to finance defence R&D. The EDF was managed by a newly established directorate-general for defence and space in the European Commission (DEFIS).

Other capability development initiatives have had the member-states in the driving seat. The EDA, an inter-governmental institution established by the member-states in 2004, has tried to foster more joint research, development and procurement of military equipment. The EDA has played a relatively minor role, because of its limited staff and budget and because of member-states’ resistance to co-operation. But it is in charge of the Capability Development Plan, which identifies what military capabilities member-states need. The agency also manages the Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence, which is meant to highlight opportunities for co-operation. Both tools however, have had relatively little impact: most member-states are part of NATO and look to its long-standing defence planning process for guidance, with the EU equivalent as an afterthought. At the same time, long-standing difficulties in exchanging sensitive information between the EDA and NATO, stemming from the Cyprus- Türkiye dispute, mean that the EDA’s prescriptions cannot easily build on what NATO has decided.

Permanent Structured Co-operation (PESCO) is another relevant EU defence tool. PESCO is a treaty-based co-operation mechanism that was launched in 2017 and involves all EU members apart from Malta. All participant countries sign up to a range of so-called ‘binding commitments’ that amount to a pledge to take defence seriously. But PESCO is also made up of 66 practical projects to deepen co-operation and foster the joint development of specific capabilities. Perhaps the best-known PESCO project is military mobility – an effort to facilitate movements of troops and military equipment across Europe, by improving infrastructure and easing regulatory obstacles. Crucially, these efforts can draw on significant financial resources from the EU budget, in particular the Connecting Europe Facility, a fund to improve infrastructure, which has a dedicated budget of €1.7 billion for military mobility.

The EU’s role in improving defence capabilities has deepened since Russia’s full-scale invasion. In March 2022 EU leaders tasked the Commission with undertaking an analysis of defence gaps, which was released in May that year. A task force on joint defence procurement sought to co-ordinate member-states’ procurement needs and mapped defence production capacity, helping identify barriers to ramping up production.15 These initiatives paved the way for the establishment of two new instruments: the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) and the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP). EDIRPA, finalised in October 2023, is worth €300 million between 2023 and 2025, and is meant to foster joint procurement by financially supporting joint purchases of urgently needed equipment. ASAP, approved in July 2023, is worth €500 million and aims to expand production of ammunition and missiles in the EU, for example by upgrading factories.

While ASAP and EDIRPA are small, they break new ground, as they point to the EU becoming involved in defence procurement. In March last year, the Commission released a new European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS), aimed at fostering long-term defence readiness in the EU. The Strategy focuses on greater self-sufficiency in armaments, with a target that Europeans should spend 50 per cent of their procurement budgets on EU kit by 2030 and 60 per cent by 2035. It also states that collaborative procurement should account for at least 40 per cent of member-states’ procurement by 2030.16

In March last year, the Commission released a new European Defence Industrial Strategy.

EDIS is underpinned by a proposed European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP), worth €1.5 billion between 2025 and 2027. The rationale for EDIP, which is currently under negotiation, is to extend and expand the support provided by EDIRPA and ASAP past their expiry in 2025 until the end of the current EU budget cycle in 2027. EDIP proposes a number of new structures, covering: 1) more joint planning; 2) financial incentives for joint procurement and expanding defence production; and 3) regulatory measures. In terms of planning, EDIP proposes setting up a Defence Industrial Readiness Board with representatives from the Commission, the High Representative and the member-states, to ensure that EU instruments are better targeted, and to identify projects of common interest. In parallel, a European Defence Industry Group with variable membership (depending on the subject) will be established to function as the Commission’s interlocutor.

EDIP also proposes several new incentives for co-operation. The most prominent would involve the establishment of a Structure for European Armaments Programme (SEAP). These would be entities with their own legal personality that groups of at least three countries wanting to procure equipment together could set up. They would then receive additional funding bonuses, for example if they agreed on a common approach to exporting equipment. EDIP mentions the possibility of waiving VAT if co-operatively developed equipment is also jointly owned. EDIP also proposes to extend ASAP’s logic of funding industry to expand production of ammunition and missiles, by giving money to firms to maintain high-capacity production facilities even in times of low demand.

In terms of regulatory measures, EDIP proposes a security of supply regime, recycling ideas already proposed by the Commission during the ASAP negotiations (but largely rejected by the member-states at the time). The idea is to ensure that defence manufacturers can deliver under all conditions, for example by mapping supply chains and prioritising domestic orders over other ones if there is a supply crunch.

More broadly, a key aim of EDIP is to foster the development of Ukraine’s defence industry and its integration into the broader European defence industrial base. Ukraine is associated to EDIP, meaning that Ukrainian entities can benefit from EU funding. Moreover, EDIP envisages the creation of a separate instrument to channel financial support to Ukraine’s defence industry. This will be largely funded with the profits from Russian assets in the EU frozen by sanctions.

The EU as an enabler of resilience

The third aspect of EU involvement in defence relates to its role in fostering resilience and preparedness. This includes being prepared to deal with all contingencies and to deal effectively with threats like disinformation and attempts at manipulation , or physical and cyber-attacks against critical infrastructure such as power plants, sub-sea cables and pipelines.

EU laws play a key role in regulating areas related to resilience and preparedness. For example, the Critical Entities Resilience Directive and the Network and Information Security 2 Directive set standards for the physical and cybersecurity of critical entities. The EU also contributes to resilience though its satellite communications infrastructure, particularly the EU Infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite network that will provide secure connectivity to member-states and their authorities. Stockpiling is another area in which the EU is involved. For example, within its rescEU strategic reserve, the EU is stockpiling medical equipment to respond to the fallout from chemical attacks or nuclear radiation; and the Critical Raw Materials Act is supposed to encourage national-level stockpiling efforts.

Finally, the EU plays a role in helping member-states deal with cyber and disinformation threats through a toolbox on information sharing and awareness raising activities, and the deployment of ‘hybrid response teams’ to assist member-states or partners dealing with cyber-attacks or misinformation campaigns.

The challenges of EU defence

The EU is still a small player in the broader framework of efforts to strengthen European security. Many of its existing tools have significant shortcomings, and there are broader political issues at stake too.

The EDF

With the EDF, the EU has established itself as a significant player in defence R&D. While the EDF’s budget appears limited, at €1.12 billion a year, it actually adds around 9 per cent to member-states’ aggregate €13 billion annual R&D spending.17 The EDF is already a success in the sense that its funding calls always attract a lot of attention from private firms. The requirement to form consortia with businesses from other countries is leading to new cross-border co-operation and should help foster a co-operative instinct over time. However, the EDF’s effects will only be felt over the long term, as it takes time to integrate new technologies into defence capabilities.

With the EDF, the EU has established itself as a significant player in defence R&D.

Evidence submitted by stakeholders to the interim evaluation of the EDF suggest that despite its positive points, there are several problems with how it works. First, its funding is too dispersed and not sufficiently connected to member-states’ capability priorities. The EDA argues these priorities are considered initially, but later lost as the Commission sets the annual work programmes of the EDF, and that “The observer role of EDA is not providing the means to mitigate that situation”.18 A scattergun approach can work when it comes to long-term innovation, as it is difficult to know which investments will pay off. However, member-states will only take up the capabilities developed if they are linked to their main priorities.

A second issue with the EDF is its funding model. The annual funding cycle is seen as an issue by many stakeholders, as it lacks long-term stability and predictability. And the EDF’s projects probably have too many participants: in 2023, for example, winning consortia had an average of 17 participants. Having fewer participants would be difficult politically, as there would be fewer winners and probably fewer SMEs participating. But it would ensure that consortia were more cohesive and that they had a higher chance of having buy-in from member-states and driving forwards larger projects. Finally, many participants in EDF-funded programmes have complained about the administrative complexity of participation – a risk to its future success.

The EPF

The EPF has played a useful role in europeanising some of the costs of the assistance given to Ukraine, in the sense that all member-states have had to contribute in proportion to their GDP. However, the EPF has been hamstrung by a range of disagreements. Member-states have argued over whether non-EU origin equipment should also be eligible for reimbursement, and there have also been disagreements about the valuation of donated equipment for which reimbursement is sought. Germany secured a mechanism to account for member-states’ bilateral assistance to Ukraine outside of the EPF, reducing its own contributions to the instrument. But the biggest obstacle has been the need for consensus between the 27, which has allowed Hungary to veto disbursements. While a workaround has been found for some of the EPF’s funding, this does not represent a satisfactory solution. At the time of writing, Hungary is still holding up €6.6 billion of reimbursements.

PESCO

PESCO has a similarly mixed record. The military mobility project is leading to concrete results, with the EU allocating the full €1.7 billion budget of the initiative to improve infrastructure, in addition to efforts to align standards and to simplify administrative procedures for moving military equipment.19

However, beyond the flagship military mobility project, PESCO has been low-key, despite successes in some areas such as setting up a rapid cyber response team that has been deployed to support Moldova.20 But the original rationale for activating PESCO was to establish a group of member-states that was deeply committed to deeper defence integration, and that has not yet happened in a meaningful way. Instead, PESCO is made up of projects largely unconnected to each other, many of which would probably have happened in other frameworks.

ASAP and EDIRPA

ASAP and EDIRPA have a more positive record. Even though these are small instruments, they have both been helpful and expanded the horizons of the type of support that the EU can provide in defence. ASAP is funding a total of 31 projects that will help individual firms in doubling production of artillery shells to a total of 2 million per year by the end of 2025.21 For example, the French firm Nexter will receive €41 million, allowing it to increase its production capacity by a factor of eight.22 EU funding has also triggered additional funding by national governments, for example in the case of a grant given to Nammo Sweden.23 Overall, the EU argues that ASAP has resulted in a total investment of €1.4 billion in the supply chain.24 Meanwhile, EDIRPA will finance five projects, each worth €60 million, to support 20 member-states in co-operatively procuring air and missile defence systems, armoured vehicles and ammunition. The Commission argues that it was able to leverage €310 million in funding to encourage joint procurement with a combined value of over €11 billion.25

EU instruments are small, with the EU being a relative newcomer in the European security landscape.

The bigger picture

Looking beyond the individual instruments, in general EU defence tools face several big challenges. First, they remain limited in size, with the EU itself being a relative newcomer in the European security landscape and most member-states looking to NATO first. Second there are questions over the design of EU instruments. The EDF, ASAP and EDIRPA, as well as the planned EDIP, are based on the EU’s competences in industrial policy. Therefore, they are designed as industrial policy tools meant to foster a competitive EU defence industry, and not tools designed primarily to strengthen member-states’ military capabilities. That has not been a big issue with ASAP and EDIRPA, as the Commission has drawn up the work programmes to address urgent priorities. But it is more of an issue with the EDF, which has not always prioritised the need to build the capabilities that European forces require.26

A third challenge to the success of the EU’s defence efforts is their closed approach towards partners. The EU’s programmes are closed to most partners – except for Norway, which is formally associated with them as a member of the European Economic Area. The EU’s approach is guided by two principles: first, EU money should not subsidise non-EU firms; and second, EU funds should not go to equipment that is subject to third country export controls or leads to dependency on a third country. These measures are primarily designed to address the issue of the US International Traffic in Arms (ITAR) regulations, which means that the US can control the onward export and (in practice) also the use of products incorporating US technology. In theory, the EU’s rules leave the door ajar for third country partners to participate, and some EU subsidiaries of non-EU firms have been involved in EU funded projects. Notably, Chemring Nobel, a subsidiary of the British Chemring, secured an ASAP grant of €66.7m to expand production of explosives for shells.27 However, firms located in third countries face conditions that are uncommon in co-operative R&D and procurement. For example, they have to waive their rights in co-operatively developing intellectual property. The third country involved would also have to waive its right to impose export controls on co-operatively developed equipment. The EU’s rules are unpopular with partners like the US and the UK. Their worry is not only about losing market share, but also that existing co-operation can be undermined by the EU’s approach. Some member-states, such as Sweden and Italy, have tried – with some success – to insert more flexibility, for example on the possibility of incorporating up to 35 per cent non-EU material (by value) in EDIRPA projects.

The tricky politics of EU defence

The politics of the EU’s involvement in defence remain complex. First, those member-states that most depend on the US for their own defence do not want to annoy Washington. The US has always been suspicious of greater EU involvement in defence, thinking that there was a risk of Europeans duplicating NATO efforts, discriminating against non-EU allies (especially in terms of procurement), and ultimately decoupling from the US. Many eastern member-states trust the US more than they do other European partners, and this makes them wary of initiatives that seem protectionist and might upset Washington.

Second, many member-states are sceptical about the Commission becoming more deeply involved in defence. Most see the Commission as a relatively new and inexperienced actor in defence, particularly when compared to NATO, and they do not trust it to make the right choices. Many member-states fear that the Commission is merely trying to gain more powers with ideas like a Defence Board for defence planning or a European security of supply regime, or when it seeks to ease the rules on cross-border transfers of defence equipment. Opposition to these proposals is visible in the EDIP negotiations. It was also prominent in the ASAP negotiations, when member-states vetoed proposals to give the Commission power to collect sensitive information about defence production capacity and supply chains.

A third issue with greater EU involvement in defence is the fact that four EU members are neutral (Austria, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta), and tend to be reluctant to see the EU being more involved in defence or directing more funding to defence.

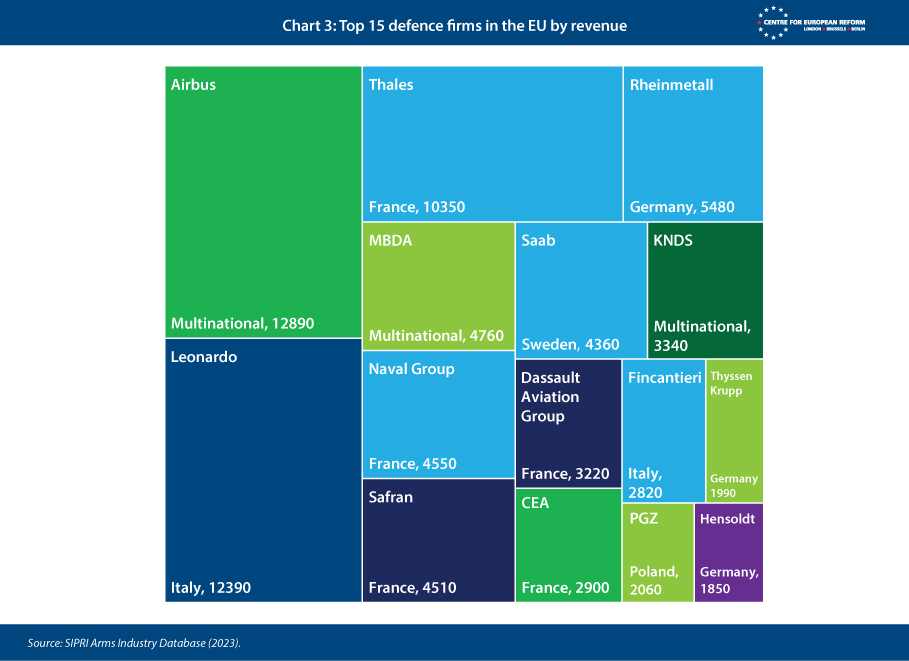

Finally, the political economy of European defence is tricky to navigate. Most of Europe’s defence industry is in its western member-states, especially in France, Germany and Italy (see Chart 3). These countries are normally supportive of EU defence industrial initiatives, so long as they think that their own industries will benefit. Countries that do not have a large domestic defence industry fear EU defence instruments will primarily benefit countries with large defence sectors. For example, countries in Europe’s east do not want to subsidise industry in the western member-states, and often prefer to buy off-the-shelf equipment from outside the EU. What unites the member-states is the desire to protect their own domestic industry, and the fear of job losses that greater competition and consolidation might imply.

This complex puzzle of interests creates fundamental trade-offs: should the EU follow the logic of efficiency, giving money to established players and trying to encourage their consolidation? Should it try to spread its funding as widely as possible, to ensure that everyone gets a slice of the pie, even if that means reducing efficiency? Is there actually a case for fostering competition between defence firms rather than consolidation?

Despite these challenges, it is worth noting that scepticism about the EU’s involvement in defence is lessening. It is notable that many countries in Europe’s north and east, which were traditionally sceptical, have become much more open to ideas about how the EU can contribute to strengthening Europe’s defences. For example, Estonia was the driver of the EU’s initiative to jointly procure 1 million rounds of ammunition for Ukraine, and together with Poland and Denmark has backed the idea of defence bonds. The selection of a Lithuanian as defence commissioner could also help traditional sceptics see EU involvement in defence in a more positive light.

The future of EU defence

Europeans face daunting challenges in strengthening their defences. The EU can play an important role in helping to fill the gaps. The degree to which the EU can do so will depend on how it approaches several interconnected questions: funding, design, partnerships, and the interplay between defence and other policy areas.

1) The funding question

National budgets are the pillars of EU defence. But ageing populations and low economic growth mean that it will be challenging for many governments to increase or even maintain funding for defence in coming years. If there is a peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine that appears to be sustainable over the long term, the pressure to increase spending may decrease further. With national budgets under pressure, there are questions over whether the EU can do more with its own resources.

One idea is to channel more funds from the current EU budget to defence. The Commission has made clear that it is possible to redirect a portion of undisbursed cohesion funds – which help reduce regional wealth disparities – to help defence firms.28 It is up to individual member-states to explore the scope to do so, but redirecting cohesion money is unlikely to be a panacea. Even if a lot of the money has not been disbursed yet, cohesion funds have been allocated to other priorities – and regions anticipating receiving some of it will be reluctant to reprioritise.

Another feasible way to raise more money is to ensure that more private finance flows into defence. In May last year, the European Investment Bank (EIB) changed its lending criteria to allow for more investment into the production of dual-use items.29 The EIB could do more to step up its lending to small defence players in particular, building on the €175 million Defence Equity Facility that it established in January last year to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in defence, and defence start-ups.

A third option is turning to joint debt, potentially raising hundreds of billions in additional funding for defence. There is now a lively debate about so-called defence bonds, originally proposed by France and Estonia. The CER has analysed the pros and cons of such funding in a recent paper.30 In essence, defence bonds could be used in several ways. For example, they could channel more resources into existing defence instruments, to set up a new fund on the model of the post-pandemic Recovery Fund, or establish a new off-budget vehicle similar to the eurozone’s bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism. Defence bonds face a number of hurdles, but the pressure for new sources of financing may well prove irresistible.

A fourth option is directing more funds to defence in the next EU budget, which begins in 2027. So far, member-states have not been willing to inject large-scale financial resources into EU defence. In negotiations over the 2021-27 MFF, Commission proposals for defence initiatives were subjected to large cuts by member-states. The negotiations for the next MFF, which are due to start in September 2025, will be a key test of the EU’s ambition. If funding is maintained at the level envisaged by EDIP (€750 million a year), then the impact on national procurement will be limited, as that would amount to less than 1 per cent of the €90 billion that the EDA expects member-states to have spent on procurement in 2024.31 Conversely, a budget of around €9 billion a year for EU procurement alone would amount to a more sizeable 10 per cent of EU-wide procurement spending, and would be a major consideration in steering national procurement decisions towards co-operative solutions, particularly if it was targeted at a few priorities.32 Additionally, the EU should consider directing funding to making critical national infrastructure more resilient, and giving grants to countries like Poland and the Baltic States to strengthen border obstacles such as anti-tank defences.

2) The design question

European defence has to navigate a complicated set of political circumstances. EU military missions can make a valuable contribution, most notably training Ukrainian troops. However, there is no solid agreement on giving the EU a greater operational role through the likes of the Rapid Deployment Capacity. For many member-states, efforts to improve the readiness and interoperability of military forces are best left to NATO and to small group frameworks. However, as the custodian of the single market, and a key regulatory body, the EU can play a highly significant role on the industrial side and in addressing non-traditional military threats like cyberthreats.

The success of EU efforts in doing so will largely be determined by the degree to which its instruments address genuine military priorities. To gain traction, EU programmes need to be targeted at addressing capability gaps, and should reflect NATO-identified priorities as closely as possible. In terms of standards, EU instruments should follow NATO standards, rather than inserting another layer of their own and hindering interoperability. In addition, Europeans will have to buttress Ukraine in the long-term and should pay attention to its military needs. Given the pace of Ukraine’s military innovation, there is also much that Europeans can learn from the Ukrainian armed forces.

EU programmes need to be targeted at addressing capability gaps.

More intense dialogue between EU bodies and NATO ones is essential, while involving non-EU allies in EU defence planning processes such as CDP or the CARD would also be beneficial. Given the difficulties in sharing sensitive information between the EU and NATO directly, EU members who are also in NATO could do more to communicate NATO priorities to the EU, ensuring that its approach reflects them as closely as possible. And the Commission should involve EDA capability experts more closely when it develops the work programmes for its defence instruments.

A second challenge is to identify capability areas in which EU funding can add value, both in term of short-term needs and longer-term industrial strengthening. In many capability areas, like fighter aircraft and main battle tanks, member-states have different strategic cultures and priorities, have recently bought off the shelf, or are already deeply committed to existing programmes. It would make sense for the EU to focus on other priorities. ASAP’s logic of funding permanently higher production capacity of consumables such as ammunition and missiles is helpful, as these are areas in which EU involvement is relatively uncontroversial. The Commission’s Political Guidelines have already singled out improving European air and cyber defences as priorities.33 These are areas where there are large gaps, and it is not easy to address them efficiently via purely national approaches.

Other promising co-operation areas are identified in the EDA’s 2024 CARD report, and include loitering munitions, underwater drones and long-range precision weapons. Enablers like electronic warfare, air transport and airborne surveillance systems could be other promising areas for the EU.34 Focusing on relatively new areas of warfare, such as uncrewed air (drones) and land equipment (robots) would be a good idea, as these are fresh pastures. There should be more scope for member-states to converge on a joint solution when there are not yet well-established national programmes. Beyond funding capabilities, the EU could consider funding infrastructure such as storage facilities and bases – both of which would free up national budgets for other priorities.35 More broadly, moving to a model of multiannual rather than annual budgets would more clearly communicate EU priorities and give a stronger demand signal to industry.

3) Avoid over-reach and get partnerships right

Attempts to create a defence single market by regulation are unlikely to succeed. Member-states have little inclination to give the Commission more power to intervene in their sovereign defence choices. Many do not see the Commission as a mature defence actor and do not always trust it to get things right. Something that looks like a single market for defence is more likely to emerge organically over time as both member-states and industry see co-operation across borders as a rational decision. The EU should focus on providing incentives in that direction, as it has already started doing.

Another priority for the EU should be ensuring a balanced approach towards partnerships. If EU countries continue to buy off-the-shelf, then the European defence industry will remain small and slow in producing the required equipment. It makes sense to try to change that by directing financial incentives towards EU firms; so does ensuring that Europeans are free to use the equipment they buy without worrying about third-country restrictions on use. At the same time, an unduly restrictive approach does not serve the EU well. First, the EU will miss out on the synergies that working with allies can bring in terms of additional funding, unique know-how and technology and lower costs due to having a larger customer base. Second, a restrictive approach risks disrupting existing co-operation between EU firms and their non-EU partners. That is particularly true in the case of the UK, which is a key player in European defence. A number of major defence firms have a strong presence both in the UK and the EU, such as Airbus, Leonardo and MBDA.

The EU would be well served if it took a more tailored approach to the involvement of partners. The Union could open its instruments to participations by partners that bring their own financing, as long as their involvement in a project does not pose an unacceptable risk, for example because of a country’s export control policies.

The EU would be well served if it took a more tailored approach to the involvement of partners.

4) Ensure defence considerations are taken into account in other policy areas

European leaders should also pay attention to the challenges that defence players face due to regulatory developments outside the narrow defence field.

Reporting requirements around environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards is a major example. Defence is not classified as an environmentally sustainable activity in the EU taxonomy of sustainable activities, and there is a perception of defence as an unethical sector in large parts of the finance community. According to a study requested by the European Commission, the defence sector is in a state of limbo: neither formally judged to be a sustainable activity nor defined as unsustainable.36

As a result, providers of finance worried about reputational damage opt to reduce their risk and exclude defence from their sustainable investment funds and sometimes all their investments. Some banks do not lend to the defence sector at all. Defence firms can also find their bank accounts closed and can find requests for export guarantees turned down. Public finance does not make up for this, particularly for SMEs. While the US and the UK have well-developed tools to support defence start-ups and SMEs, in the EU that can only be said of France. Encouragingly, improving access to finance for defence companies is one of Andrius Kubilius’ priorities.

The issue of defence financing is only one example of how regulation in one sector impacts defence. As Niinistö’s report highlights, regulation of new technologies, such as AI, will also affect the defence sector, and determine whether Europe can be at forefront of innovation.37 In general, it is essential that EU policy-makers consider the implications for defence whenever they embark on new lawmaking efforts.

Conclusions

Europeans have avoided taking their defences seriously since the end of the Cold War, calculating that there were no major threats on the horizon and that they could always rely on the US to provide security. Putin’s full-scale war against Ukraine has made clear that Europe is no longer safe, while Trump’s return to the presidency casts serious doubt on the US’s dependability as an ally.

Europeans have recently made some progress in strengthening their defences, but much remains to be done. The EU has the potential to play an important role in that endeavour, in complementarity with national efforts and other frameworks. The future of the EU’s defence efforts will be shaped by how policy-makers approach the questions of funding, by how the EU structures its defence tools, and by its stance towards partnerships. The degree to which policy-makers take defence considerations into account when dealing with other policy areas will also be a major factor. An open, pragmatic approach, sharply focused on Europe’s military needs would serve Europeans well.

2: European Defence Agency, ‘Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence Report 2024’, November 19th 2024; European Defence Agency, ‘Defence data 2023-24’, December 4th 2024.

3: European Commission, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Defence Investment Gaps Analysis and Way Forward’, May 18th 2022.

4: European Defence Agency, ‘Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence Report 2024’, November 19th 2024; European Defence Agency, ‘Defence data 2023-24’, December 4th 2024.

5: Jan Joel Andersson, ‘Building weapons together (or not): How to strengthen the European defence industry’, EU Institute for Security Studies, November 23rd, 2023.

6: European Commission, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Defence Investment Gaps Analysis and Way Forward’, May 18th 2022.

7: Yuliia Dysa, ‘EU has supplied Ukraine with over 980,000 shells, Borrell says’, Reuters, November 11th 2024.

8: European Commission, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Defence Investment Gaps Analysis and Way Forward’, May 18th 2022.

9: See Ben Schreer, ‘Europe’s defence procurement since 2022: A reassessment’, IISS, October 23rd 2024.

10: Dutch Ministry of Defence, ‘13 Light Armoured Brigade completes integration between Dutch combat brigades and German divisions’, March 30th 2023; Royal Netherlands Navy, ‘Admirality Benelux’, accessed January 8th 2025.

11: Shephard News, ‘NATO signs contract for 1,000 Patriot missiles’, January 5th 2024.; European Defence Agency, ‘Seven EU Member States order 155mm ammunition through EDA joint procurement’, October 2023.

12: Council of the EU, ‘Ukraine: Council extends the mandate of the EU Military Assistance Mission for two years’, November 8th 2024.

13: European Council, ‘EU joint procurement of ammunition and missiles for Ukraine: Council agrees €1 billion support under the European Peace Facility’, May 5th 2023.

14: European Parliament committee on the internal market and consumer protection, ‘Report on the implementation of Directive 2009/81/EC, concerning procurement in the fields of defence and security, and of Directive 2009/43/EC, concerning the transfer of defence-related products’, March 8th 2021.

15: EDA, ‘Joint procurement: EU Task Force presents conclusions of first phase’, October 14th 2022.

16: European Commission, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A new European Defence Industrial Strategy: Achieving EU readiness through a responsive and resilient European Defence Industry’, March 5th 2024.

17: €13 billion is the EDA’s estimate for EU member-states’ R&D spending in 2024.

18: EDA, ‘Submission to the consultation on the interim evaluation of the European Defence Fund’, February 20th 2024.

19: European Commission, ‘Joint report to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of the Action Plan on Military Mobility 2.0 from November 2022 to October 2023’, November 14th 2023.

20: EEAS, EDA, EU Military Staff, ‘Factsheet on the Cyber Rapid Response Teams and Mutual Assistance in Cyber Security (CRRT) PESCO project’, Accessed January 2025.

21: European Commission, ‘ASAP results factsheet’, March 15th 2024.

22: KNDS, ‘La Commission européenne octroie à Nexter une subvention pour accompagner la montée en cadence de la production de munitions pour l’Ukraine’, March 19th 2024.

23: Government of Sweden, ‘EU financial support for increased ammunition production in Sweden’, March 19th 2024.

24: European Commission, ‘The Commission allocates €500 million to ramp up ammunition production, out of a total of €2 billion to strengthen EU’s defence industry’, March 15th 2024.

25: European Commission, ‘EU boosts defence readiness with first ever financial support for common defence procurement’, November 14th 2024.

26: Douglas Barrie, Bastian Giegerich, Tim Lawrenson, ‘European missile defence - unstructured co-operation?’, International Institute for Strategic Studies, August 26th 2022.

27: European Commission, ‘Results of ASAP funding’, June 7th 2024.

28: Paola Tamma, ‘Brussels to free up billions of euros for defence and security from EU budget’, Financial Times , November 11th 2024.

29: EIB, ‘EIB board of directors steps up support for Europe’s security and defence industry and approves €4.5 billion in other financing’, May 8th 2024.

30: Luigi Scazzieri, Sander Tordoir, ’ European common debt: Is defence different?, CER policy brief, November 5th 2024.

31: The specific amount that EDIP would devote to procurement as opposed to expanding industrial capacity is not yet clear, so €750 million is likely to amount to significantly less than 8 per cent of procurement.

32: Figures on procurement from European Defence Agency, ’Defence data 2023-24’, November 29th 2024.

33: Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Europe’s choice: Political guidelines for the next European Commission 2024-2029’, July 18th 2024.

34: European Defence Agency, ’Co-ordinated annual review on defence’, 2024 report, November 19th 2024.

35: Jan Joel Andersson, ’Building weapons together (or not)’, EU Institute for Security Studies, November 16th 2023.

36: Laura Delponte, Francesco Giffoni, Anthony Bovagnet, Francesa Picarella, Thomas Tanghe, Gaetano Caccavallo, Ralph Thiele, ‘Access to equity financing for European defence SMEs’, European Commission, 2024.

37: Sauli Niinistö, ‘Safer together – Strengthening Europe’s civilian and military preparedness and readiness’, October 30th 2024.

Luigi Scazzieri is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

January 2025

View press release

Download full publication