Europe and the global economic order

- Europe’s share of the global economy has been shrinking over time, a trend that is likely to continue as growth in Asia and America outpaces European growth. This is a threat to European influence.

- The EU’s share of global trade has nevertheless remained relatively stable as the European economy has grown more trade-intensive. The ‘Brussels effect’, whereby European regulations have global effects due to the size of the European market depends on the EU’s role in the global economy. It is not clear if the EU can continue to compensate for a diminishing share of GDP with increased trade intensity.

- The relatively stable period after the Cold War, characterised by US dominance and increasing globalisation, is giving way to competition between major powers (like the US and China). This instability is particularly worrying for Europe, as its economy depends heavily on international trade and stable global markets.

- Over-reliance on regulations risks undermining EU openness and its attractiveness as a trading partner. While regulations can be beneficial, excessive or overly stringent regulations can make it difficult and costly for other countries to trade with the EU. This can reduce the EU’s attractiveness as a trading partner and thereby also weaken the EU’s regulatory influence.

- The Brussels effect allows the EU to influence global regulatory standards, but its effectiveness depends on the EU’s economic weight in global trade. Therefore, EU regulations should be targeted and prioritised to minimise burdens on the European economy and maintain openness. Extraterritorial regulations (those that apply outside the EU’s borders) should be reserved for high-priority cases.

- The EU should co-operate closely with the US, leveraging the Trade and Technology Council as a forum to resolve or manage trade disputes, co-ordinate policy and engage in regulatory dialogue.

- The EU should manage its relationship with China carefully, both embracing the opportunities for European consumers while selectively confronting China when strategic interests dictate.

- To safeguard stability, the EU should help build a supplemental legal order outside the World Trade Organisation (WTO), through both continuing to expand its global network of free trade agreements and allowing neighbouring countries to plug into its markets and regulatory sphere.

The mood in Europe is glum. Growth in Europe has been mediocre and slower than in the US and Asia. As a result, Europeans fret over declining purchasing power. At the same time, the global order put into place after the Cold War is now increasingly fracturing under the pressure of renewed great power rivalry. For Europe, a trade-intensive economy that relies heavily on exports for economic growth, this is a particular concern.

Europe’s response so far has been to help uphold as much of the WTO system as possible, while relying increasingly on unilateral regulations, and its status as one of the most important trading partners to many countries, to influence the development of regulatory standards overseas. But relying too heavily on regulation to set the agenda brings its own set of risks: it requires the EU to set more conditions on access to its own market. In doing so, it risks undermining EU openness and its importance as a trading partner, which is the reason why other countries follow its standards in the first place. There are increasingly signs that, in imposing these new conditions, the EU has gone too far.

Europe has diminished influence, but is still vital in trade

A continent that 100 years ago dominated much of the world is now seeing its importance steadily diminish. The decline manifests itself in several ways. First, from a demographic perspective, Europe’s share of the global population has been shrinking rapidly for decades. While in 1960, the EU, the UK and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries still had almost 14 per cent of the global population, in 2023 that share has been reduced by more than half to 6.6 per cent.

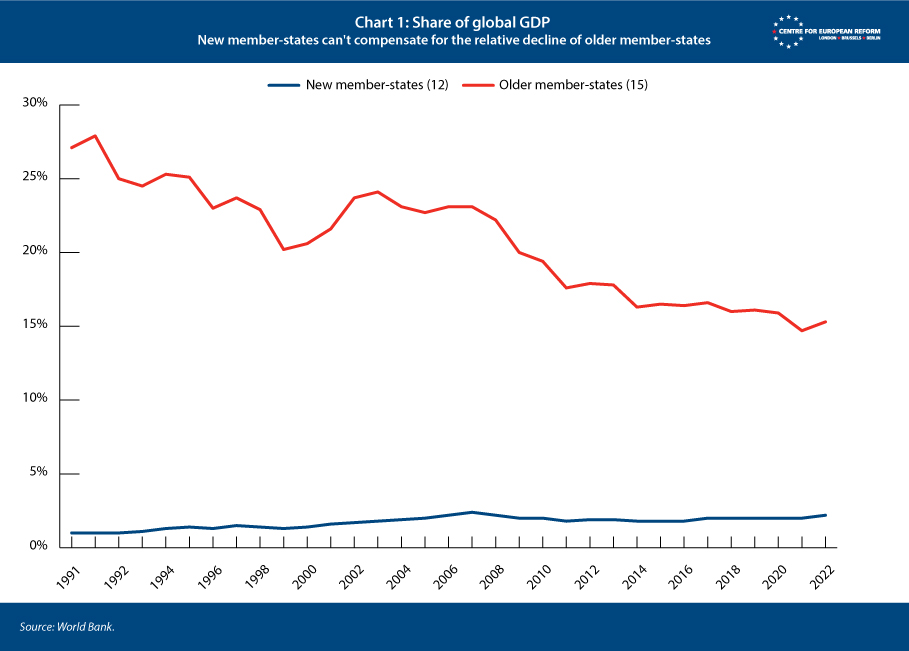

Second, the EU has reduced economic weight. The current EU-27 countries contribute 16.5 per cent of global GDP, going up to 21 per cent if the UK and EFTA are included.That is substantial but down significantly from 1960, when the figures were 28 per cent for the EU-27 and 38 per cent including the UK and EFTA. The relative decline of the older member-states has only been minimally compensated for by the economic resurgence of Central and Eastern Europe after its liberation at the end of the Cold War (Chart 1).

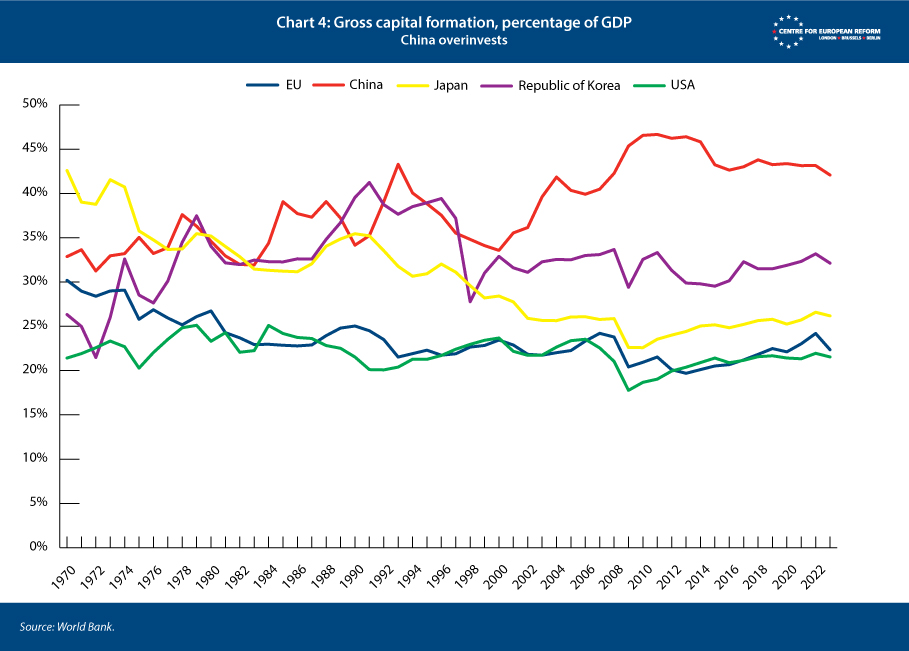

Economic growth in the rest of the world is outpacing that in Europe. The US retains control of the commanding heights of the information economy, and has ample domestic energy supplies along with an unmatched capacity for innovation. Although growth in China is slowing down and there are signs that its investment-led growth model is reaching its limits, it retains significant potential for continued catch-up growth. Moreover, India is now growing rapidly and looks set to become a significant global player.

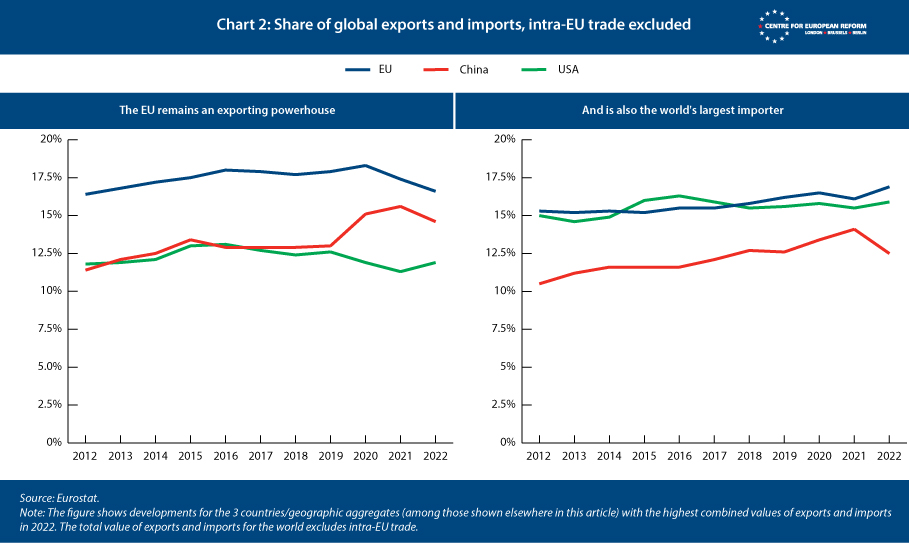

In other areas, Europe’s weight in the global economy has held firmer. Europe’s share of global trade has held steady over the last decade (Chart 2). Its share of exports kept rising steadily until 2020, while its share of imports has risen continuously.

Europe has performed strongly in trade because, unlike China and the US, it has grown more trade-intensive over time. Trade as a percentage of GDP in the EU-27 is now almost twice as high as in the US and is also significantly higher than for China. Smaller economies are generally more trade dependent, and the EU is unusually reliant on trade for its size.

The EU has compensated for its decreasing share of the global economy with increased openness and higher trade intensity.

There are several reasons for this. The EU is an export-reliant open economy, surrounded by a number of countries that are closely associated with it through close economic ties: Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Turkey and others. Although it does on occasion resort to trade defence measures – as with Chinese electric vehicles – it has refrained from the more blatant forms of protectionism such as US-style tariffs. But domestic consumption has stagnated since the pandemic. As a result, Europe relies on access to international markets. Exports to the US, in particular, have become increasingly important.

The EU’s share of global trade is perhaps the best measure of its influence over regulatory standards, as it measures the extent to which other countries interact directly with the EU. From that perspective, the EU has been able to compensate for a decreasing share of the global economy with increased openness and a higher trade intensity: as the EU’s share of GDP has gone down, trade’s share of EU GDP has gone up (Chart 3). However, it is not clear that this trend will persist as the EU’s share of GDP continues to decline.

The global context: A fraying legal order

The EU, as a creature of international law, arose as the natural solution for a continent that has learnt in the hardest possible way the value and importance of an international legal order. After World War II it was only one of several such institutions – arguably the most successful one – created to avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1930s. However, because the EU is trade-dependent it is also reliant on the international trade order underpinned by the WTO.

The WTO was never designed to handle great power rivalries and during the Cold War it never had to.

The purpose of the WTO is to create an environment that is predictable and avoids the trade wars that contributed so greatly to the Great Depression. The ambition was never to create a level playing field in the European sense, but rather to ensure a minimal level of openness among WTO members, and provide a mechanism to address and channel trade disputes to reduce the risk of tit-for-tat escalation. The WTO was never designed to handle great power rivalries and during the Cold War it never had to, since the communist states were not members of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) that later evolved into the WTO. Given the dominance of Western countries in the global economy at the time, this meant that in practice the WTO was dominated by like-minded and often allied countries, which facilitated progress in negotiations as well as dispute resolution.

After the end of the Cold War, the GATT turned into the WTO and gradually become a less Western-dominated and more universal and inclusive organisation. The inclusivity also made it harder to advance negotiations. The last major successful revision that led to substantially increased market access was the Uruguay round, which was concluded in 1994. Since then, only smaller agreements, and so-called plurilateral agreements that do not cover all WTO members, have been achieved. A principal reason for this is that multilateral agreements require consensus and, as the world becomes more multipolar, more countries are willing to block negotiations. A country like India, which was a minor player in the early years, eventually acquired the heft and confidence to say no, which New Delhi has often done since the 1990s, and with gusto.

In 2001, China joined the WTO. At the time, Western countries hoped that gradual integration into the world economy would turn China into a Western-style market economy and perhaps even a democracy. This hope has not been fulfilled. Instead, China’s entry into the WTO has further contributed to the deadlock within the institution. China’s export success has been founded upon the classical East Asian model followed by Japan and South Korea: repress consumption, and channel savings into investment to promote export-led growth (Chart 4).

If a country is small enough, this can pass unnoticed, but this was the main source of global trade tension in the 1980s when the US and Europe worried about Japanese car exports. For China, with a population ten times larger than Japan, the trade tension is greater still.

There is little chance of China changing its economic model. Even though the Chinese growth model is showing signs of exhausting its potential, it has brought China 40 years of strong economic growth and lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.1 Excess savings pay for industrial subsidies, and cheap access to capital is fuelling phenomenal growth in production capacity for manufacturing, ranging from electric vehicles and solar panels to semiconductors and shipbuilding. The WTO rules are ill-equipped to handle this kind of non-market practice. Although export subsidies are illegal and there are mechanisms to impose countervailing duties in response to unfair subsidies (as the EU is now doing with electric vehicles), countries with concerns about China believe they cannot identify, document and quantify the full extent of Chinese subsidies. In other areas of Chinese policy, such as economic policies that suppress wage levels or encourage savings, non-market practices do not breach WTO rules. Those rules allow China to be treated as a non-market economy – a status that in theory makes it easier to impose higher anti-dumping duties. The procedures for imposing such duties are cumbersome, however, so the practical effect of China’s status has been limited. The EU has, for instance, had anti-dumping tariffs in place on Chinese bicycles since 1993, with little discernible effect. Chinese market practices are systemic and intrinsic to the Chinese model, while each lengthy WTO process only offers localised relief to specific sectors.

An additional factor contributing to the decline of the WTO is the US’s long-standing dissatisfaction with its dispute settlement mechanism, which the US feels overstepped its bounds in some cases, including in cases unrelated to China. As a result, Washington has blocked appointments of Appellate Board members, rendering the WTO dispute settlement mechanism ineffective since 2019. In the public debate, many commentators blamed this on the Trump administration’s unilateralism, since the Appellate Board became unable to resolve disputes under his watch, but the concern was bipartisan, and the US first stopped the appointment of members under Barack Obama.

This is not the first time that global trade tensions have put the international legal order under strain. For instance, in the 1980s under the Reagan administration, the US had concerns about its trade deficit that were very similar to the concerns voiced by Donald Trump and others today. The dispute was first addressed by Japan’s voluntary export restrictions in 1982, followed by the Plaza Accords in 1985 that aimed at reducing the US trade deficit through a weaker dollar. But that was an agreement between US allies and like-minded countries with high levels of mutual trust. That is radically different to today’s situation where China and the US see themselves as geopolitical antagonists. A similar diplomatic solution today is difficult to envisage.

The US has largely liberated itself from the constraints of WTO rules in practice, while still paying lip service to them.

Since the demise of the Appellate Board, the US has largely liberated itself from the constraints of WTO rules in practice, while still paying lip service to them. WTO exemptions that allow for deviations on national security grounds have been routinely abused to justify tariffs on everything from steel and aluminium to electric vehicles. The Inflation Reduction Act, for instance, contained ‘Buy American’ provisions that were in blatant violation of WTO norms, and the Biden administration made little effort to justify them. WTO rules do allow for certain forms of subsidy in limited circumstances. And without any functioning Appellate Board, any dispute raised in the WTO can be ‘appealed into the void’ without ever getting resolved.

Moreover, the US has responded to China’s market-distorting practices with its own separate set of market-distorting programmes, in the form of industrial policy to promote US manufacturing. Although the EU has in turn also loosened its rules for industrial subsidies, the scale is limited. The European Chips Act for instance only had €3.3 billion from the EU budget. Allowing member states to subsidise more also risks undermining the level playing field of the single market, a key EU achievement.

What can Europe do?

The EU is then confronted with a situation where the US is increasingly disregarding the WTO, while China has market-distorting mechanisms that are difficult to address inside it. Since the two of them account for over 40 per cent of global GDP and more than a quarter of the EU’s exports, this represents a significant weakening of the global trade order.

How has Europe responded to this rising uncertainty? The EU has been at the heart of the Multi-Party Interim Arbitration Agreement (MPIA), a voluntary arrangement that replicates the WTO Appellate Board for countries that choose to participate. In addition to the EU, members include Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan and others. This is vital because it allows the EU and China to continue resolving bilateral disputes within the WTO framework as before. The electric vehicle tariffs that the EU is imposing on China will for example inevitably face a challenge from China in that system. This allows the system to work as intended in containing trade disputes, albeit without the US.

Can Europe be regulator to the world?

With the lack of progress at the WTO, there is a need for alternative ways to regulate global trade. Brussels has become enamoured with the so-called ‘Brussels effect’, namely the process by which EU standards often become de jure or de facto global standards due to the size of the EU market.2 Countries can easily adopt EU standards because EU law has traditionally been seen as high-quality, non-discriminatory and capable of transposition into different legal systems. Companies can apply EU standards everywhere, since they are typically the most exacting. The Brussels effect was named by Columbia Law School professor Anu Bradford in 2012 and popularised in her 2019 book.

However, the Brussels effect emerged through EU standards which evolved through technocratic processes – often with the close involvement of foreign companies, for example in standard setting organisations – with the main aim of sensibly regulating the European market. EU regulations became globally influential mostly as a side-effect, often market-driven, as companies found it easier to comply with one set of rules, and at other times because governments found it easier to copy EU regulations rather than developing their own set. Recently, however, the EU has increasingly deployed the Brussels effect actively, as an extra-territorial tool to enforce change globally.

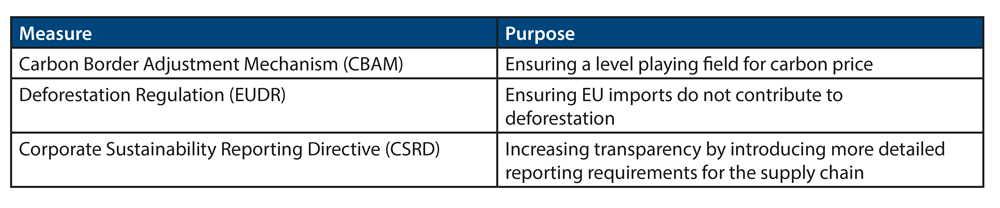

Looking specifically at the major trade-related measures that have been passed in the last few years is illustrative in this respect:

Each of these directives has a laudable objective. But each also increases the regulatory burden for both EU companies and their trading partners elsewhere. Increased regulatory requirements not only increase costs, but they tend to favour larger, more established companies that have the resources to comply. While CBAM in particular may be justified as necessary for a level playing field in a context where European producers will increasingly have to pay for carbon pricing, the other two represent examples of Europe taking it upon itself to enforce global governance through trade-related regulation.

Regulatory costs must be proportional to the desired goal and must take into the account the viability of the EU enforcing rules.

Moreover, the costs of regulations are cumulative for the economy and a significant burden for the private sector. But while the costs add up for the private sector, the benefits are dispersed across the range of objectives that regulations are meant to achieve. There is no real overlap between the objectives of the CSRD and the EUDRR for example: they are meant to help deliver discrete benefits for the world as a whole, and not Europe specifically. Each regulation may or may not end up delivering on its purpose, but the costs are certain and likely to be paid mostly by European importers. As a result, Europe has taken upon itself to pay high costs to help deliver a range of uncertain global benefits. The intention is noble, but it not clear that Europe can afford to be so selfless.

The Brussels effect depends on the EU being a large and indispensable market that justifies the economic cost of compliance. This requires the EU to have a certain weight in the global economy and global trade. Without that weight, regulations risk turning into self-defeating protectionist mechanisms that only make the EU a less attractive trading partner without achieving their stated aims. And to the extent these regulations make the EU a less open and more protectionist economy, they also risk reducing Europe’s weight in global trade and therefore European influence in general, creating a vicious cycle that could weaken the Brussels effect over time.

An important aspect of the Brussels effect is that it relies on companies finding it easier to comply with one set of rules than multiple ones: just complying with the strictest one can make sense. But while it is one thing to do this if you are a tech company with a global platform, it is not at all clear that this will be the case in the supply chain for raw materials and industrial goods for instance. In that case, it might make more sense to apply the stricter, more expensive regulation only when you have to. This would further reduce the Brussels effect and leave the EU as the less-favoured trade partner instead of being in a position to have a global impact through its rules.

There are already signs that the implementation of new regulations is becoming an increasing burden on trade. Both the Deforestation Regulation and CBAM are faced with implementation difficulties as trade partners are not yet ready to comply with the extensive reporting requirements, if they ever will be. Unlike CBAM, where importers can compensate for lack of regulatory preparedness by paying the carbon price, with the EUDR importers that are unable to comply will simply be unable to trade at all. The EU recently postponed implementation of the EUDR by one year to 2026, although it is not at all clear that trade partners will be readier to implement it then than now. To the extent Brussels law-makers thought the Brussels effect meant that regulations could be imposed without a competitive cost to Europe, that should be a warning that this is not the case.

The Brussels effect is important and does allow the EU to shape global regulatory standards in significant ways. But since its efficacy depends on the EU’s weight in global trade, European regulation must be highly targeted and prioritised to minimise the burden on the European economy and maintain openness. In particular, the use of explicitly extraterritorial regulations that target trade should be reserved for only the highest priority cases. CBAM is an example of a regulation that is clearly targeted and aimed at supporting a cause with high priority: climate change. It is in that sense strategic in both of its immediate goals: encouraging reduced emissions and levelling the playing field for EU producers. The same cannot be said for EUDR and the CSRD. Regulatory costs must be proportional to the desired goal and must take into the account the viability of the EU enforcing rules. By trying to do too much, the EU risks only harming itself without achieving its goals.

Navigating the new global order

How then can Europe navigate this new environment and retain its influence over global regulatory norms? It must first wake up to the need for growth: the EU is unlikely to increase the share of its economy which is trade dependent, so its only option is to increase the size of its overall economy.

That means first creating the conditions for economic growth at home. The Draghi and Letta reports should provide some impetus for more growth-oriented policies. It is unfortunate that the European Union has chosen to frame the problem in terms of competitiveness, however. European exports are in fact highly competitive, and the EU has consistently run a large trade surplus with the rest of the world, with only a brief interruption during the 2022 energy crisis. But a country can be poor and unproductive while still remaining competitive if it can keep its production costs low enough. Europe should instead focus on boosting productivity and innovation through higher investment. This can be done through public investment, but the more plausible path is to enable private investment through completion of the Capital Markets Union and the Banking Union. Although the Banking Union faces political obstacles, both Draghi and Letta rightly point to the Capital Markets Union as key to replicating the financial infrastructure that enables US innovation.

To preserve the Brussels effect, Europe must ensure that it maintains its openness to trade.

Meanwhile, Europe must accept that its global influence, while still substantial, will diminish further in the foreseeable future. To preserve the Brussels effect, Europe must ensure that it maintains its openness to trade. As an export-reliant trade bloc it needs to evaluate carefully whether the positive effects of regulations like CBAM and the Deforestation Regulation justify the increased cost and impact on growth. This need not require abandoning European environmental commitments, but it does mean better prioritisation to maximise the impact of the Brussels effect when necessary. In the case of CBAM, there is a strong case to be made for its necessity.

Second, while China and the United States are important trade partners, more than 70 per cent of EU exports go elsewhere. The European Union remains an attractive trading partner, both because of the size of its internal market and because it is now less protectionist than the other two major trade blocs. Unlike China, the EU plays with transparent rules and to a much greater degree than the US it has so far been willing and able to open its markets through free trade agreements. Free trade agreements have traditionally been seen by many trade policy experts as a competitor to progress in the WTO. But in a world where the WTO is under threat, any legal commitment to trade that is compatible with WTO law should be seen as a strengthening of the global legal order.

A key litmus test is the contentious ratification of the free trade agreement with Mercosur.3 Mercosur represents a market of 300 million people in democratic, like-minded countries that have substantial trade barriers and high tariffs on key European industrial exports. An estimated economic boost of 0.3 per cent of GDP may seem modest at first, but for a continent that is struggling to eke out 1 per cent annual growth, that would be a welcome contribution.4 Closer ties would also derisk Europe’s economy by diversifying export markets and improving relations with a key supplier of critical raw materials. Similarly, although the road to concluding an FTA with India is longer, finalising negotiations with the world’s most populous country should be a top priority for the same reasons: it would help deliver growth and the EU is uniquely positioned among the major trading blocs to do it, since neither the US nor China is likely to conclude a free trade agreement with India.

The EU, with its commitment to international law and a rules-based international order also has a uniquely open architecture that allows the European Economic Area (EEA) and other countries, like Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the UK to plug into its regulatory framework. This is a competitive advantage that should not be wasted. The EU has red lines that need to be respected: there has to be a level playing field with a balance between market access and responsibilities, as famously illustrated with Michel Barnier’s diagram of a staircase during the Brexit negotiations.5 However, the EU would benefit from considering these relationships as strategic tools that help position the EU at the centre of an emerging regional trade order with a global impact instead of just managing each relationship in isolation.

In managing its relations with Switzerland and the UK, this could mean placing greater value on the strategic importance for the EU of these countries aligning with EU regulation. This effectively enhances and extends the EU’s regulatory sphere and therefore its role in the global trading system. Bilateral flexibility and even generosity help strengthen the EU’s position globally. Renewed efforts could also be made to extend the EU’s regulatory influence beyond the borders of Europe to any willing partner.

Last, but not least, the EU must manage its relations with the US. The transatlantic economy remains the world’s largest and most important and the EU has no substitute partner for the US, either in terms of security or as an export market. That means Europe must of necessity stay close to the US. There is little point in hoping for a US return to the WTO fold. The bipartisan consensus on this in Washington is strong, and US contributions to WTO reform efforts have been perfunctory at best.

The EU has no substitute partner for the US either in terms of security or as an export market.

The EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) set up under the Biden administration will therefore have to serve as the main forum for trade policy co-ordination with the US. The TTC can serve at least three functions. First, it is a forum for dispute settlement and management. The TTC helped put both the steel and aluminium dispute and the Boeing-Airbus dispute on ice. In this respect the TTC harks back to dispute settlement in the early years of the GATT, which was similarly more diplomatic than legal in nature. That function should be embraced and developed.

The TTC also serves as an important forum for regulatory dialogue and co-operation. Although the concrete results have been limited, the TTC’s role as a forum for dialogue has value. Dialogue helps avoid surprises and increases mutual understanding. It also simply helps officials get to know each other, boosting ad hoc co-operation. Gina Raimondo, the US Secretary of Commerce, has for instance cited how the TTC facilitated the coordination of sanctions on Russia in the aftermath of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The EU would be well-served by developing the TTC further as a cornerstone of transatlantic relations.

Close alignment with the US does not necessarily entail adopting the US point of view wholesale. The US perspective on China specifically reflects a great power rivalry in East Asia where Europe, despite very real concerns about the situation around Taiwan and the South China Sea, does not have exactly the same perspective or interests. But the rise of China as an economic competitor poses real challenges to the EU as well, particularly as Chinese industry climbs up the value chain and is increasingly becoming a competitor in key European export sectors such as machine tools and vehicles.6

Increasing US efforts to isolate China and enlist allied nations in its cause are adding to the pressure. The partially successful US attempts to exclude Chinese telecom manufacturers such as Huawei from Europe are the best example. Another is the drive to push EU member-states, notably the Netherlands and Germany, to expand restrictions on the exports of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China. The US spent considerable diplomatic capital in pursuit of these goals and has been met with resistance but also partial success. Europe therefore finds itself under pressure to side with the US or China. If forced to, Europe will side with the US, but the European preference is to maintain trade relations with both. This remains true, even with a separate set of rising EU-China trade tensions.

So far, the EU has managed its disputes with China well within the WTO framework. Brussels will continue to take a selective approach – as the Draghi report recommended – picking the most important battles instead of engaging a broad trade war with China, as the Draghi report recommends. This is a sensible strategy. Global consumers have benefited from the Chinese model over the last 30 years, accessing a vast array of inexpensive Chinese-manufactured goods, boosting consumer purchasing power. Moreover, the Chinese overcapacity in certain areas will be of enormous help for key European strategic interests, for example in enabling cheap solar energy for the energy transition. In those cases, if China wants to supply subsidised goods, Europe should take as much as it can get, especially while Europe’s own production capacity remains woefully insufficient to meet its climate targets.

EU willingness to take advantage of China’s economic model must be balanced against three considerations: the impact on European labour markets, strategic risks connected to excessive dependency for certain goods, and the relationship with the United States.

The EU’s work on derisking supply chains is still in its infancy, but for many products there is an excessive reliance on one supplier, often China, which means that the supply chain has a so-called single point of failure, as for instance with permanent magnets. Reducing dependency on one supplier would be sensible, but this does not necessarily mean paying for European production. It could instead mean working with partner countries to co-operatively develop alternative sources that could take a part of the market, without completely shutting China out at a very high cost to consumers. Here again, a selective approach is needed, keeping in mind that for many global supply chains with single points of failure, that single point is in Europe. It is not possible or desirable to eliminate all such points globally, nor is the pursuit of it an example the EU should want to set.

Conclusion

Europe’s influence on global regulations is in relative decline. But it remains one of the three large trading blocs that set the tone in the global economy and wield significant power over global trade. Since power is ebbing away from Europe, it is all the more important for the EU to leverage its unique characteristics to make sure it continues to be an indispensable player in global trade. The key priorities should be maintaining good relations with the US, extending its trade arrangements with other countries aggressively and using a selective approach with China, picking disputes where Chinese policies threaten key European interests while embracing the opportunities that China offers global consumers where this serves European interests. By doing so, it can continue to influence global affairs for the foreseeable future.

2: Anu Bradford, ‘The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world’, Oxford Academic, December 19th 2019.

3: Mercosur is an economic and political bloc consisting of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.

4: Uri Dadush and Michael Baltensperger, ‘The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and risks’, Bruegel, September 24th 2019.

5: Michel Barnier, slide presented to the heads of state and government at the at the European Council (Article 50), December 15th 2017.

6: Sander Tordoir and Brad Setser, ‘How German industry can survive the second China shock’, CER policy brief, January 16th 2025.

Aslak Berg is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform

January 2025

View press release

Download full publication