Why cities must drive growth in the EU's single market

- This year the EU has commissioned two reports by former Italian prime ministers, Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi, to set out policies to raise Europe’s anaemic growth rate. The long shadow of the financial and euro crises, Covid-19 and the energy price shock after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have all contributed to the continent’s disappointing economic performance. But so too have several long-standing problems with the EU’s economic structures. Letta has called for ‘more single market’ – deeper internal EU economic integration – as a way to raise competition and productivity. Draghi is likely to do the same when his report comes out in July.

- In this paper – which is the first to comprehensively assess the winning and losing subnational regions from trade within the EU – we identify four key facts that policy-makers should consider when pursuing more single market integration:

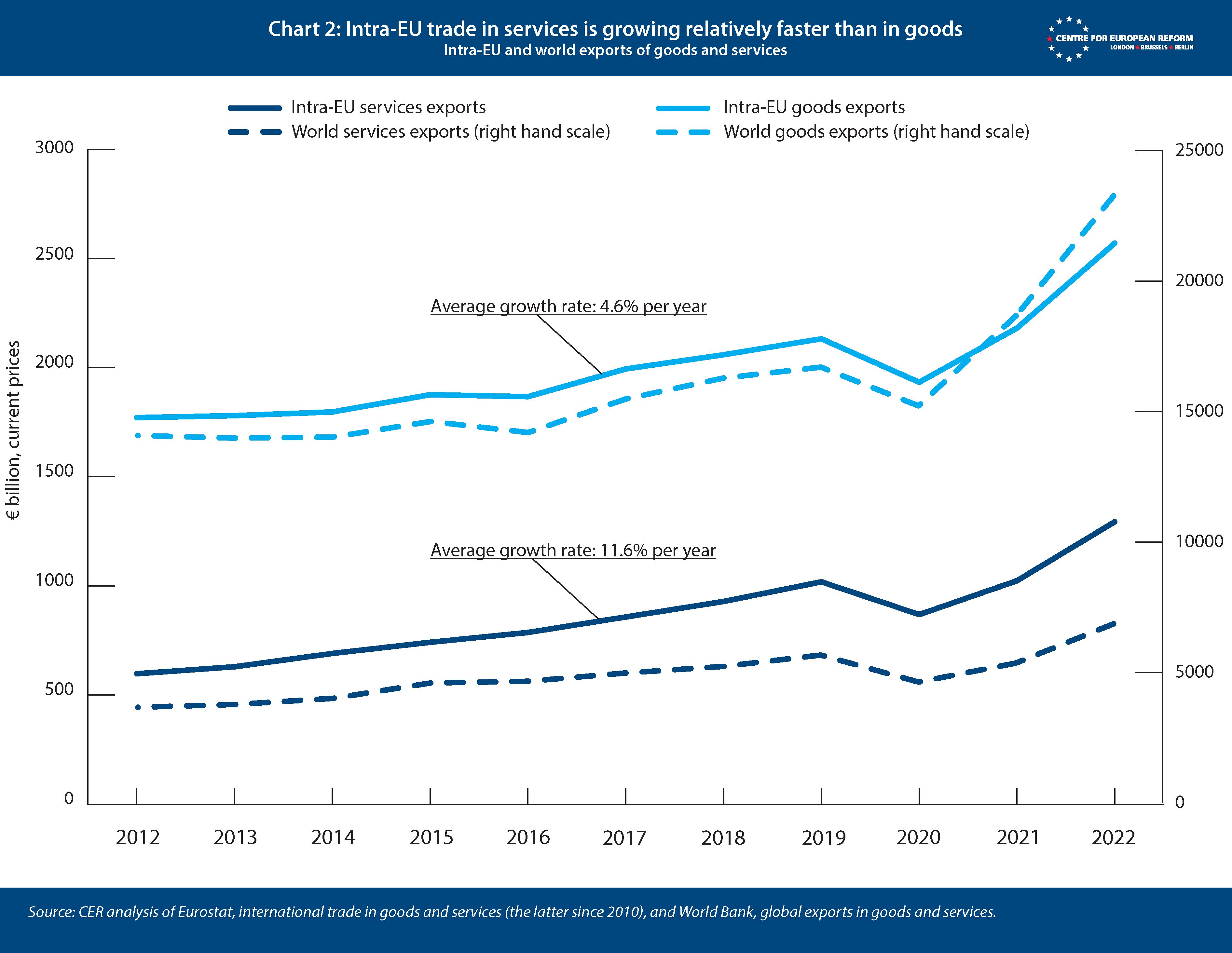

1. Integration of goods markets has slowed. Since 2012, intra-EU trade in goods has grown no faster than global goods trade, in contrast to previous decades: the 2004 enlargement, for example, saw rapid growth in manufacturing capacity in Central and Eastern Europe, raising trade within the single market.

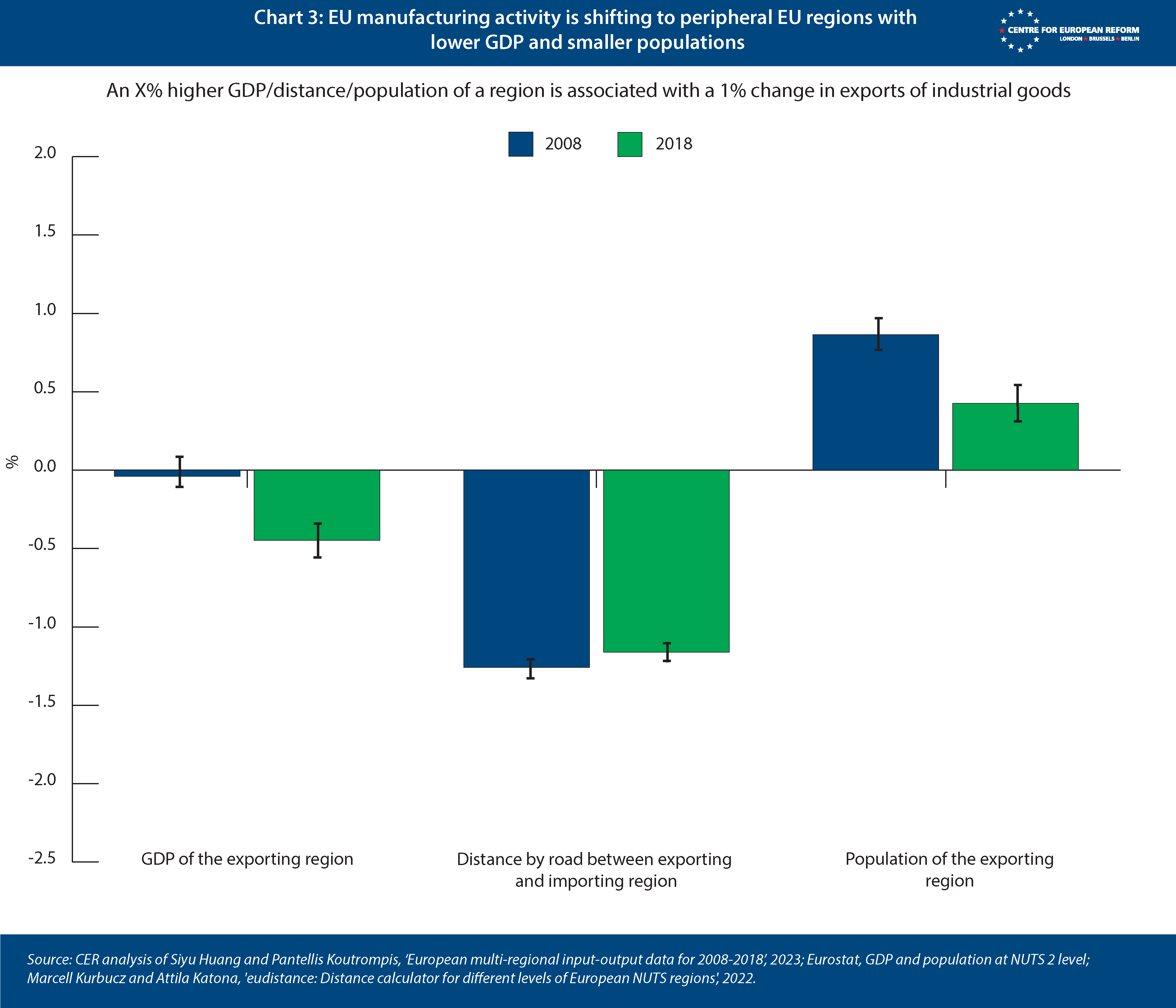

2. Goods trade is a ‘convergence engine’. As we show using a ‘gravity model’ (of the type that correctly predicted large Brexit costs), between 2008 and 2018 poorer and less populous regions of the EU became, on average, increasingly important sites for export-oriented manufacturers to locate factories. That is because they are constantly on the hunt for cheaper land and labour. But it is unlikely that there will be further big integration wins in goods trade as production costs in newer Central and Eastern member-states converge with the EU average – at least until Ukraine and other candidate states accede, probably in the 2030s.

3. Services trade, on the other hand, has been growing much more rapidly within the single market than globally. And it has been catching up with goods trade within the EU – by value, it has grown from a third of goods exports in 2012 to a half in 2022. While the single market for services is by no means ‘complete’, the movement of skilled service workers and capital, and the provision of cross-border services, is far easier within the EU than outside it. And there is much more that the EU could do to reduce barriers to trade in services – which would raise growth.

4. Services trade tends to be ‘centripetal’, however – with exporters clustering together, often in large and rich cities. We show that, if anything, this process has strengthened: a region’s success at exporting services is increasingly associated with the hallmarks of a ‘knowledge economy’ – high numbers of graduates, workers in tech, science, finance and other specialist fields, and effective and non-corrupt governance. Further single market integration in services will tend to reward already rich and successful places, with the potential to drive further political wedges between liberal cities and their more conservative hinterlands.

- If it wants to raise growth, the EU should move forward with its stalled capital and banking union projects; create European markets in telecoms, energy and online services; and try again to remove national regulations, such as professional qualifications, insurance mandates and language requirements that discriminate against services providers from other member-states. But it should also reform its regional spending, known as ‘cohesion policy’, to tackle the divergences that services trade promotes.

- With Central and Eastern Europe rapidly converging with Western European living standards, more regional funds should be directed towards city-regions with high growth potential, complementing existing allocations based on relative poverty. Many post-industrial cities have struggled, as productive services firms have chosen richer cities. To spread the economic benefits of agglomeration, we propose that the EU should identify ‘growth city regions’ in each member-state. These are non-capital cities that have the potential to become bigger centres for tradeable services – be they tech, engineering, finance, design or education. Money should be spent on:

1. Improving transport links within these cities and with surrounding towns. This will improve matches between workers’ skills and employers, by creating larger labour markets within commutable distances.

2. Raising the density of cities – much as better metropolitan transport expands labour markets, so does concentrating more workers and employers together in space. EU funds could be used to provide other infrastructure that facilitates that density, such as water, energy and telecoms.

3. Improving energy efficiency and electrification. Cities are more energy efficient than more sprawling patterns of settlement, but net zero will entail a large rise in electricity demand, with heating, transport and industry all needing to be electrified. Lower energy costs will make cities more productive.

- The EU should also locate any new agencies, and Horizon-funded research and development institutions in these growth city-regions and encourage national governments to do the same. These can help form the clusters of expertise that private companies can draw on and encourage them to move operations there. Choosing Paris for the European Banking Authority and Amsterdam for the European Medicines Agency, instead of second-tier knowledge hubs, this was a missed opportunity.

- City-regions should have a bigger role in choosing which projects are EU-funded. In many member-states national or state governments are in charge, and too much funding is disbursed without input from cities, which are increasingly the key unit of economic geography.

- This strategy would be politically challenging, as it would entail funds being distributed less by rules – a region’s GDP relative to the EU average; and more by judgement – which regions have the most capacity for growth? But, by integrating European services markets and investing in cities that have the potential to take advantage, the EU would raise growth and spread activity beyond successful metropolises. The EU should, however, continue to provide funds to poorer regions that are struggling to converge with European living standards.

1. Introduction

As its new legislators assemble following June’s European Parliament election, the EU is faced with major economic challenges. The European economy expanded at 2 to 3 per cent annually throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, but growth has never fully recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. While Europe continues to rank highly on broader measures of well-being, its growth has fallen well behind that of the US. Boosting growth is vital for Europe to deal with high levels of public debt, demands for higher spending on defence in the wake of Russia’s war on Ukraine, investment needed to curb emissions, and a rapidly ageing population.

Europe faces other looming threats. The US and China are subsidising industries and protecting domestic markets. The EU economy is highly exposed to this turn towards economic nationalism by major trading partners: the share of extra-EU foreign trade to GDP stood at over 40 per cent in 2021, vastly more than that of the US and China.1 China is also ramping up production of goods like electric vehicles and machinery, leading to an export glut that threatens Europe’s cutting-edge manufacturing sector. Europe also lags in technology creation and diffusion, just as artificial intelligence might unlock new productivity gains.

The search for higher economic growth, and the risk of global fragmentation, has rekindled European ambitions to deepen economic integration within Europe. Built to deliver unfettered movement of goods, services, capital, and labour across member-states, the EU’s single market has fostered trade, generated investment and stimulated growth. But there has been little progress on completing the single market for services – the largest sector of the economy, and the least integrated – in the last 20 years. Capital also remains ring-fenced along national lines despite the EU’s capital markets and banking union projects. Reducing such barriers to trade and investment would boost competition and dynamism by allowing more productive firms in any EU country to capture market share from less productive ones –and become more competitive in global markets. The EU tasked former Italian prime ministers Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta to make proposals in this direction and guide economic policy in the years ahead.2 Letta published his report in April, whilst Draghi is expected to do so in July 2024.

A more integrated single market, however, puts the spotlight on a longstanding challenge that has received less attention: regional disparities. The single market has been instrumental in raising standards of living for many regions and for the EU as a whole. At the same time, it has contributed to widening the economic gap between the EU’s metropolitan cities and successful industrial centres on the one hand, and post-industrial cities and more peripheral regions on the other.3 Intra-EU services exports are growing rapidly, despite regulatory barriers, but tradeable services firms tend to congregate in already prosperous cities. The EU is also edging towards another round of enlargement, with the accession in the medium to long term of Ukraine, Moldova and countries in the Western Balkans. Manufacturers may once again cut costs by shifting supply chains to poorer member-states, just as they did after the 2004 expansion to Central and Eastern Europe. This could trigger jitters about losses of manufacturing capacity elsewhere in Europe, especially now that Chinese import competition is also intensifying.

This dynamic, where internal market integration and the incorporation of new member-states raises growth but creates regional winners and losers, requires reforms to the EU’s regional policies. The EU should target resources on the places that may be able to take more advantage of trade within the single market. That has the potential to raise growth, but it must be handled carefully: the EU must also provide resources to regions that show less promise but need better infrastructure, technology and skills.

Using a dataset on goods and services trade within the single market between 2008 and 2018, this paper identifies how and where trade activities are concentrated, assesses shifts in regional trade patterns over time, and determines which regions have managed to leverage the single market to their advantage and which have been left behind – and why. As the EU contemplates expanding the single market in services and capital, the EU should consider a reformed cohesion policy that provides resources to city-regions that need help to take advantage of lower barriers in the services sector.

2. Trade in Europe: Clustering and compensation

There are two opposing forces that are unleashed when barriers to cross-border trade are lowered. The first is a geographical clustering of activity: lower barriers allow some factories and offices to take advantage of larger markets, and to draw in capital and workers from less successful companies and regions. The single market allows economic factors to move freely, or at least at a lower cost, so in some cases capital and labour will tend to cluster together to exploit economic benefits that come with higher concentration. Companies benefit from lower transport costs and better infrastructure, a larger pool of workers, and easier access to know-how that other firms have come up with. Such economies of scale are often accompanied by stronger competition, which in turn drives efficiency and innovation within the market.4

The second is centrifugal – production can also be more easily ‘unbundled’ across a larger market, with design and engineering taking place in places where workers have the requisite skills, and manufacturing in places where workers on lower wages live. That makes the use of Europe’s capital, land and labour more efficient, and promotes income convergence between the EU’s regions by enabling both types of regions to grow, but the low-wage ones more quickly as manufacturing tends to have higher productivity growth.

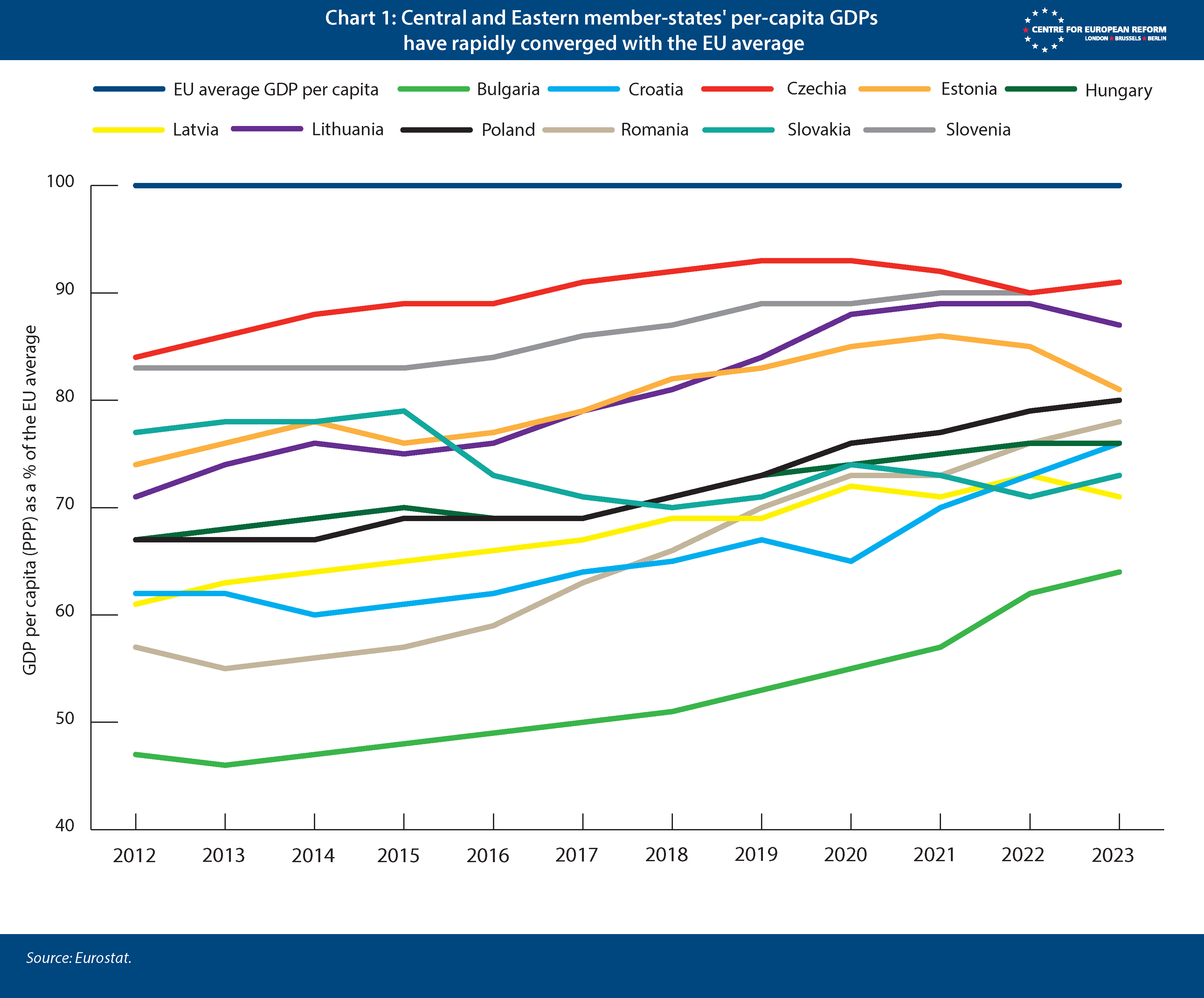

These dynamics, which together raise efficiency, productivity and innovation, explain why the EU has been striving towards ever-deeper trade integration within the single market for over 30 years. The single market has lifted the EU’s GDP by an estimated 9 per cent.5 But the gains from it already vary strongly, with regions in the geographic core of the EU enjoying income gains of up to €3,600 per capita, in contrast to more peripheral regions where increases were as modest as €150 euros, according to estimates by the Bertelsmann Foundation.6 However, across countries the single market has led to very large gains in income, especially for new member-states, as shown in Chart 1.

While market integration raises average output, it comes with downsides for firms that are out-competed, or workers who cannot move freely to more productive regions or firms. Regions that are geographically distant from major economic centres or hubs tend to lose out. The ‘costs of remoteness’ include higher relative transport costs, higher interest rates for businesses seeking to expand and limited access to human capital, knowledge and other resources.7

In the deliberations over the creation of the European Regional Development Fund in 1989, the Commission argued that the free movement of goods, labour and capital would not narrow the gap between new EU member-states like Portugal and Spain and the rich European arc (running from south-eastern England to northern Italy). The EU introduced its ‘structural funds’ to help European regions that did not have sufficient electricity, railways, ports or paved roads to participate equally in European trade.8 Such physical infrastructure is especially important to enable regions to export manufactured goods. Since the beginning, the aim of the EU’s cohesion policy has since been to improve infrastructure, skills, technology and buildings in poorer and more remote regions. Today, the EU dedicates around one-third of its budget – which comprises just over 1 per cent of EU GDP – to this aim. However, the impact of cohesion policy on fostering regional growth has been mixed. Some studies point to its success in promoting growth, at least for short periods, while others suggest it has not sufficiently addressed the structural weaknesses of lagging regions.9

Since cohesion policy’s inception, the dynamics and geography of trade in Europe have changed rapidly. Manufacturing has moved from large integrated industrial complexes to geographically-dispersed specialist component manufacturers and assembly plants, which allows big European companies to make things where it is cheapest to do so. This initially created big opportunities for convergence in incomes between poorer and richer regions.10 But in the last decade, goods exports within the EU single market have grown no faster than goods exports globally (see Chart 2).

Meanwhile, trade in services within the single market has been growing rapidly over the last decade – much faster than in goods, and significantly faster than global services trade (Chart 2). Intra-EU services exports were worth around a third of goods exports in 2012, but rose to around half by 2022. The EU is already a service-led economy: services now account for around 70 per cent of value added in the EU. And trade in services can still grow a lot: despite services trade within the EU doubling from 3 per cent to 6 per cent of GDP between 1993 and 2021, it still lags the more integrated goods sector.11 More services sector integration would further increase the share of services in EU GDP and boost productivity.

2.1 EU goods trade has been a convergence engine, but more for newer member-states than older ones.

Some regions have benefitted more than others from the continued growth in goods trade within the single market – and the same is true of faster-growing services trade. But which ones? And do the patterns of winning and losing regions allow European policy-makers to continue to claim that the single market is a convergence engine?

The enlargement of the EU after 2004 provided an excellent opportunity for European manufacturing conglomerates to relocate production, since land and labour were much cheaper than in the older member-states. The strictures of EU membership also improved national economic policy, and EU spending on infrastructure reduced energy costs and made it easier to ship goods from east to west.12 The cost advantages of newer member-states, combined with the scorching pace of Chinese manufacturing investment in the 2000s, constituted a shock to some industrial regions, especially in the UK, France and Italy.

The euro crisis compounded the shock; the failure to resolve the banking crisis quickly and the initial refusal of the European Central Bank to act as a lender of last resort to governments meant that interest rates in Southern Europe surged, with negative consequences for investment and growth. More recently, Germany’s economic problems since 2018 – notably weak public and private investment, and Chinese competition in its key sectors – have meant that it has also lost ground.13

The forces underpinning the relocation of manufacturing and services activity in Europe can be seen in a ‘gravity’ model that we have constructed. The model uses an experimental set of EU regional trade data developed by Siyu Huang and Pantellis Koutrompis at Oxford University, to identify whether poorer, less populous and more distant European regions exported more in 2018 than in 2008.14 This tells us whether the EU single market, working in concert with the EU’s regional policies, is aiding convergence: higher exports are strongly associated with higher productivity and higher income.15 Each region’s exports are estimated using transport data, so they should not be treated as the last word on the subject, but the model shows some potentially important trends. For more details about the model, please see the appendix.16

Chart 3 shows the results of the model for industrial goods (combining the manufacturing and heavy industry sectors). The relationship between distance and industrial exports was consistent between 2008 and 2018: if an exporting region was 1 per cent further away from the importing region, its exports were around 1 per cent lower (see middle bars). While controlling for the impact of distance on intra-EU trade, the negative impact of a region’s GDP on trade has grown (left hand bars), whereas the importance of a region’s population has roughly halved (right hand bars). The change in the coefficients between 2008 and 2018 is driven by goods exports rising more quickly in less populous and poorer regions. The model therefore shows that manufacturing activity has been shifting to regions with lower GDP and lower populations over the decade, as manufacturers have sought cheaper land and labour.

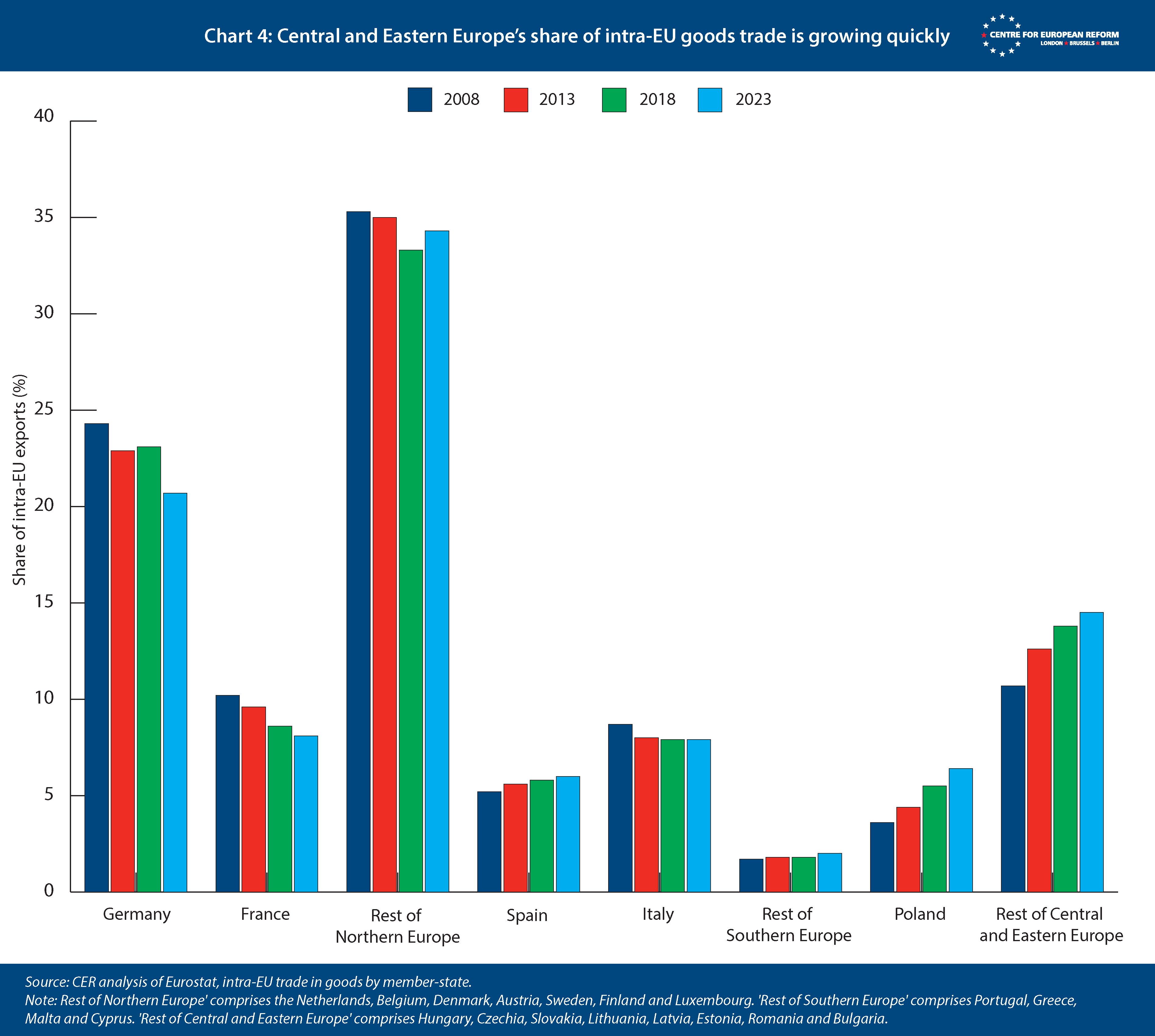

Unsurprisingly, this dynamic has helped countries with lower wages and cheaper land. Chart 4 shows that the shares of intra-EU goods exports of France, Germany and Italy fell between 2008 and 2023. Poland and other Central and Eastern European countries saw their shares rise substantially. The EU has provided a more powerful convergence machine for Central and Eastern European countries than for Southern Europe over the last two decades, to the extent that several have now overtaken Spain, Portugal and Greece in GDP per capita, and many more are likely to do so this decade.

2.2 Knowledge workers, professional services, infrastructure and quality of government have become less important to regional goods exports.

The characteristics of regions that excel in EU goods trade have also shifted dramatically over ten years, according to our principal components analysis (PCA). A PCA is a statistical method that simplifies a large dataset with many variables into a smaller set of patterns (see appendix for more details).17 We applied the PCA to a dataset we built based on regional trade and Eurostat data and the European Commission’s competitiveness index from 2010 and 2019. Our dataset includes variables for European regions in several categories.18 These include infrastructure (such as railway connections), institutions (like corruption and the effectiveness of government services), connectivity (the proportion of households with access to broadband), education (the proportion of the population with tertiary education), innovation (patent applications) and business sophistication (employment in professional, scientific, and technical activities).

The PCA clusters regions according to their similarity in terms of economic, institutional, and infrastructural variables. Our PCA thus reveals which European regions have similar characteristics in 2008 and 2018. The more closely correlated these variables – share of knowledge workers, say – are to goods and services exports, the more they are associated with a region’s success or failure to export. This allows us to examine the characteristics of regions that export more – are those regions with larger populations or more knowledge workers also bigger exporters? The results of a PCA are hard to understand visually because they represent the clusters of variables and regions in three-dimensional space. We therefore present those in the annex. In the following section we interpret the results of the PCA, coupled with descriptive statistics that function as a simplified visualisation of the PCA’s clustering.

In 2008, the regions that excelled in goods trade had higher GDP and larger populations. But they also tended to be regions with stronger knowledge economies: their firms issued more patents and had higher R&D expenditure, and a higher share of employment was in finance and technology. Regions that displayed these characteristics included, for example, Brussels, London, Athens and Paris but also areas like Liège in Belgium, Emilia-Romagna in Italy, the Calais region in northern France, Duisburg and the Ruhr area in Germany.

By 2018, as industry continued to shift to Central and Eastern Europe and other less wealthy regions, the relation between both GDP and population on the one hand, and goods exports on the other, collapsed (see Chart 5). As manufacturing companies sought lower labour and land costs, being a wealthy, populous and high-patent intensity region no longer seems to help attract investment (see Chart 5).

Our method also allows us to examine which EU regions have the right ‘cluster’ of characteristics that are associated with goods exports (see appendix for a fuller explanation).19 Regions in Poland, Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia moved closer to the cluster around goods exports, while quite a few regions in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and some in France and Spain retained their place. Yet many regions in Italy, Spain, and Portugal – countries that were most badly affected by the euro crisis – seem to have lost out: in the PCA these regions have moved away from the goods exports cluster.

These dynamics are also visible when we look at 25 regions that either saw their industrial exports within the single market decline significantly or grow strongly (see Chart 6). There are outliers – some regions in both older and new member-states performed well or poorly. But around half of the regions with the highest growth in manufacturing exports between 2008 and 2018 are in Central and Eastern Europe – and there are quite a few in Spain and Greece located further from the European economic core (See Chart 6a). The regions that saw very steep declines in goods exports are overwhelmingly in France, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark, though (for example) Catalonia in Spain and Berlin in Germany also rank amongst them (Chart 6b).

The PCA also confirms that industrial processes have been rapidly unbundling within Europe’s single market, with greater specialisation in various regions. Unbundling of manufacturing activities across regions refers to the process where different stages of production are separated and distributed across various geographic areas to optimise costs, resources, and efficiencies. Some regions in Western Europe retain remarkably strong industrial goods exports as a result. These include, for example, the Stuttgart region, home to highly specialised and high-end German Mittelstand manufacturers, and Mercedes-Benz. It also includes Brabant in the Netherlands, the region in which the industrial cluster for semiconductor machinery is concentrated, led by the firm ASML, which has a near-global monopoly on the most advanced chip-making machines. North-Central Sweden, known for steel production and housing major manufacturing plants for firms like Volvo and Saab also continues to be part of the cluster of manufacturing-exporting regions.

Across all of Europe’s regions, by 2018 almost all the variables that correlated strongly with goods trade in 2008 had become much less important. But regions that in 2008 had high scores in patent applications and product innovation, like Brabant or Stuttgart, continue to be in the cluster of regions with strong goods exports by 2018. This suggests that ‘old economy regions’ that manage to marry industrial and knowledge prowess can hold their own, and are not affected by the forces of the single market that push manufacturing towards low-cost regions.

The big picture confirms what one sees in the gravity model. By 2018, Western Europe’s once dominant comparative advantage, based on hubs of large, populous, rich and skilled regions, and those with many patent awards, had diminished. Institutional indicators like the rule of law lost significance as Central and Eastern European regions emerged as new goods exporters, with other variables also declining in importance. The reason is that the design, engineering, component manufacturing and assembly elements of goods production are now located in different regions.20

2.3 The single market for services has contributed to convergence between countries, but has led to divergence within them.

Overall, the single market in goods has continued to be a convergence machine, albeit one that has disproportionately benefited regions in member-states that joined after 2004. But what about services? After all, tradeable services also offer a route to higher incomes for Europe’s regions. ‘Tradeability’ is almost by definition a measure of productivity: if it is possible to locate an office in one region, and use it as a base to service hundreds of thousands of customers in other regions, productivity is likely to be high in terms of output per input. And higher productivity means higher income.

But tradeable services firms tend to favour larger cities – often capitals. There are benefits to having a large pool of highly skilled workers for employers to choose from, so workers and firms tend to cluster together geographically. Yet there are hopes that the internet and other information and communication technology (ICT) are making more services tradeable, allowing parts of the production process to be unbundled, just as has happened with goods.21 Back-office functions like database management and call centres can be moved to cheaper locations, and artificial intelligence may allow more services to be automated. And both the single market in services and the capital markets union programme are intended to reduce national restrictions on services trade, which may offer more opportunities for regions outside major cities to get in on the action. Moreover, ‘digital nomads’ like software engineers are often happy to move to lower-cost cities, such as Lisbon in Portugal.22

Our gravity model allows us to see whether the single market in services is helping to reduce regional inequality in Europe, just as it does in goods. If the effect of distance, GDP and population on exports of services is diminishing over time, regions outside major cities are winning business. Chart 7 shows that is not the case. Even in ‘low knowledge services’ – sectors such as logistics and warehousing – there is no evidence that production of tradeable services has been spreading into more distant or poorer regions. There is however, some evidence that it is spreading into less populous ones, perhaps in part because warehousing for online retail required cheap land for the enormous distribution centres that have been built. The same static picture is true of high knowledge services, which remain highly concentrated in cities – regions that have large overall GDPs.

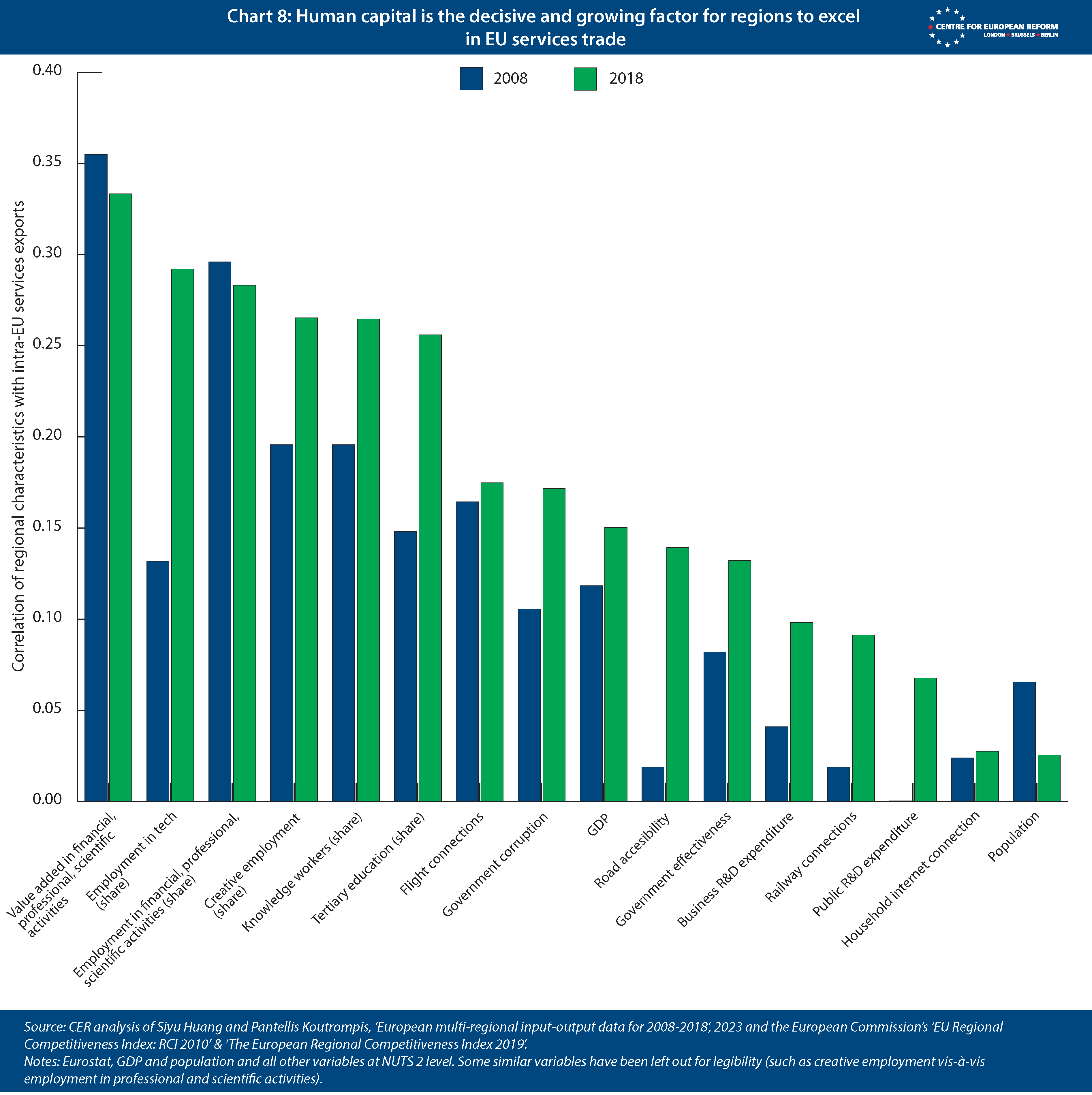

A PCA on the characteristics of successful services exporting regions also shows that services trade has not been a convergence engine, unlike trade in goods. Services exporters are mainly – though not only – concentrated in capital cities across Europe. In 2008, knowledge economy and transport indicators strongly aligned with success in services exports. These indicators include the share of knowledge workers, patenting, transport connections (passenger flight connections, railway access and motorway connections) and albeit more loosely, GDP and population. But as Chart 8 shows, by 2018 these factors continued to be important, and if anything, their importance had grown.

Between 2008 and 2018, then, human capital probably became more important, with services exports correlating more closely with factors like the proportion of knowledge and technology workers. And the relationship of GDP and population to services exports tightened. Regions with higher GDPs and populations – the largest cities – became more successful at services exports, as did those with a higher proportion of workers in tech or creative sector employment, that have a university education, or work in science. Connections to rail, air and motor transport also still mattered. But success in European services trade is ultimately a story about having and attracting skilled people.

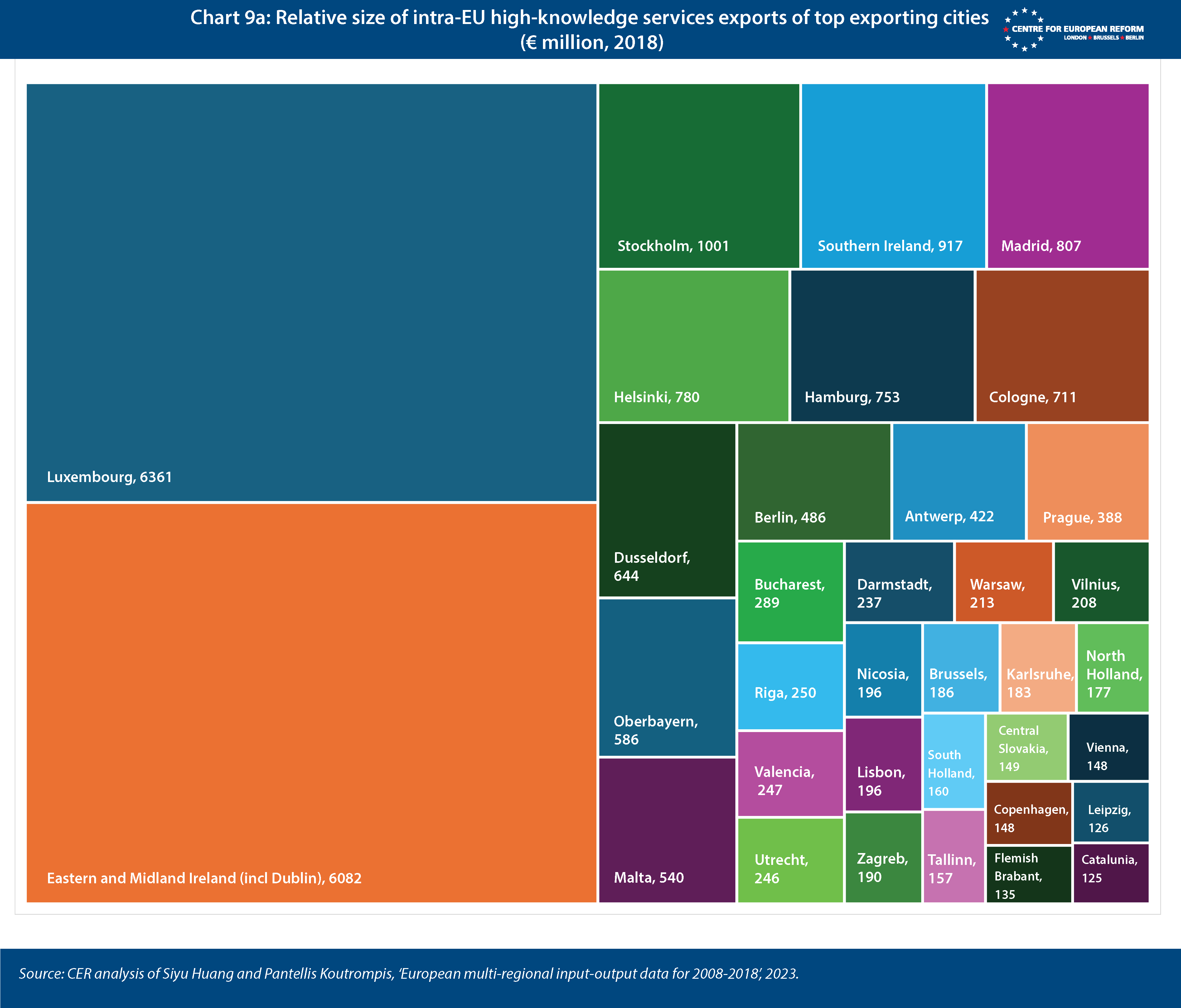

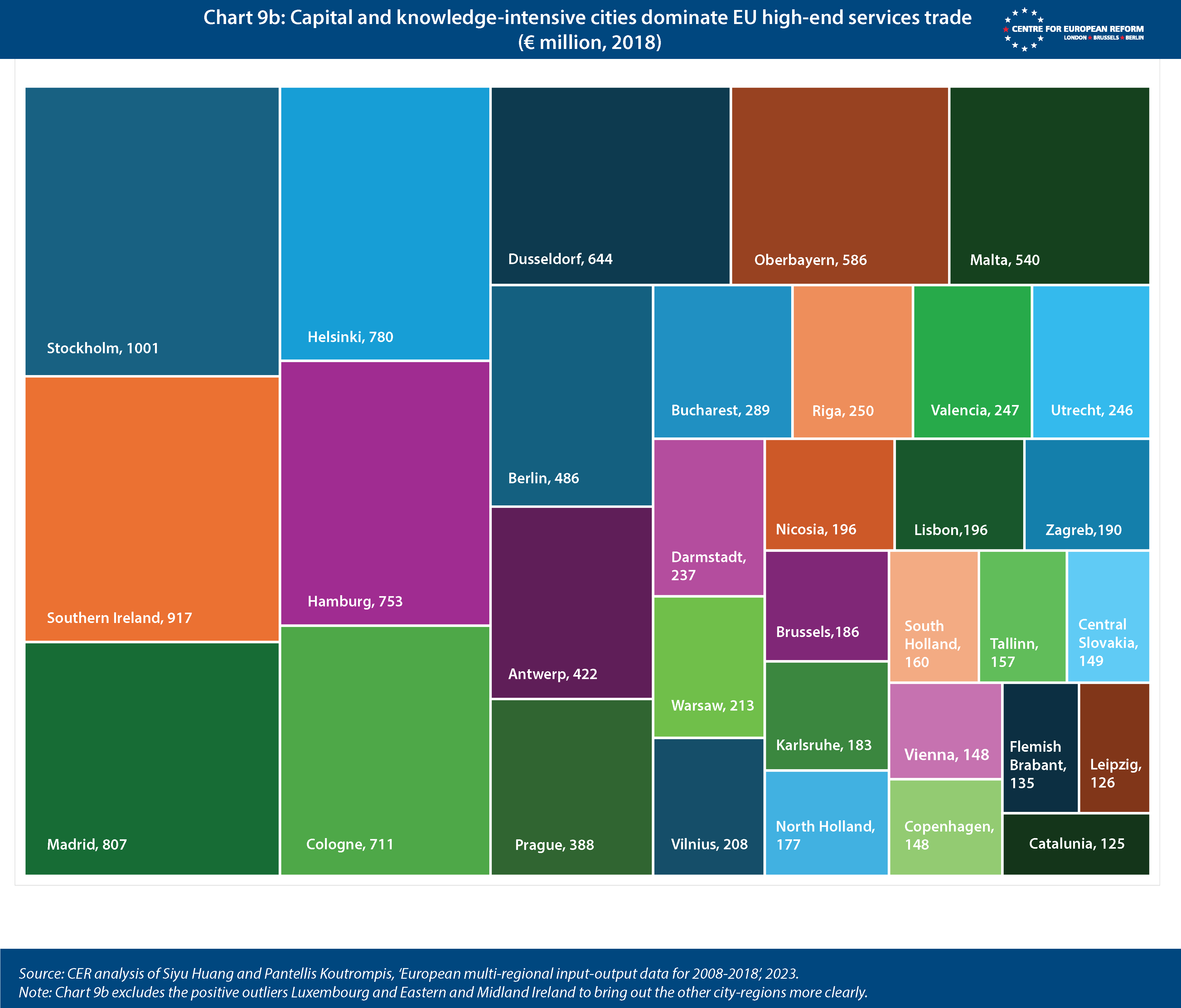

In other words, being a knowledge hub mattered even more for a region’s services exports in 2018 than it did 2008. The observations that make up this cluster of exporting regions in the PCA include many of the major capital cities of Europe for which we have data (see Chart 9a and 9b). This suggests that the drivers of services exports include higher education, government institutions and the accumulation of human capital.

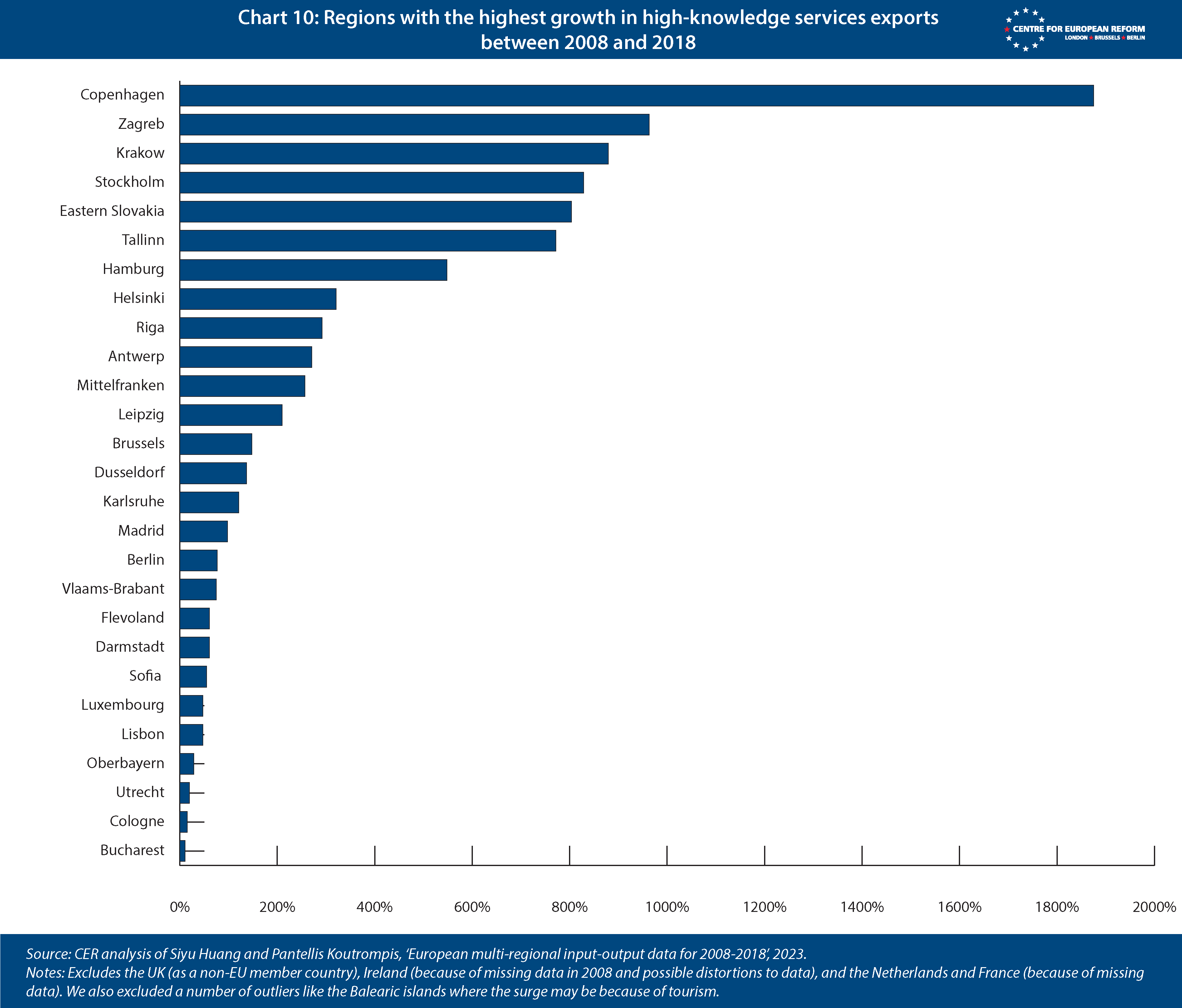

Critically, the observations not only include major cities that are service-exporting powerhouses, like Stockholm or Luxembourg. The capitals of smaller member-states are also part of this cluster in the PCA, and in fact, capital cities as diverse as Lisbon, Athens and Prague have moved closer to the heart of this cluster of observations between 2008 and 2018 (see appendix). It is also striking that a few countries – not just regions – have features that make them excel at services exports, including Germany, the Netherlands and Luxembourg and, now outside the EU, the United Kingdom. Chart 10 shows the top-performing regions in growth of intra-EU services exports.

The capital cities of Central and Eastern Europe provide an interesting illustration. Economic disparities within these countries are on the rise, in part because large cities are outperforming the rest of the country. Bratislava, Prague, Budapest, Warsaw and Vilnius all have higher per-capita income than the EU average. Prague’s income per capita is double the EU average, and Warsaw is more than 50 per cent above it.23

But this is not only a story about capital cities that already had a strong base of skills achieving high economic growth rates. A closer look at regions that managed to strongly grow their services exports from 2008 to 2018 reveals several different types of city in which services exports have been rising. They can be broadly sorted into four categories:

- Diversifying port cities (Antwerp, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Valencia)

- Resurgent capital cities (Berlin, Lisbon, Vilnius, Tallinn)

- Second-tier knowledge and creative cities like Leipzig and Karlsruhe in Germany, Krakow in Poland and Malmo in Sweden

- The ‘next door’ cities that are close to a capital city like Leuven in Brussels or Utrecht in the Netherlands.

The single market for services, therefore, can be seen as a ‘between country’ convergence machine, whilst increasing within-country disparities.

3. EU cohesion policy is ill-suited for this new phase of economic integration

On April 18th, former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta published his long-awaited report on the future of the EU’s single market, entitled ‘Much more than a market’.24 He described the single market as unsuited to a world where the EU’s share of the world economy is shrinking and where it faces competitors less willing to play by norms of open and fair competition.

Letta has proposed a wide range of reforms, in particular to rekindle the EU’s stalling capital markets union through harmonisation in some areas and a joint supervisory authority. Such markets continue to play a minor role in credit provision in the EU: banks account for 90 per cent of household debt and 70 per cent of business debt.25 A more integrated capital and banking market would enhance financial services trade within Europe, increasing the market’s size and competition and lowering firms’ funding costs.26

The single market for all other types of services is also hampered by regulatory differences. Harmonising national regulations in licensing and local insurance requirements, public procurement, consumer protection and tax frameworks would improve the tradeability of EU services. This could also involve the creation of optional EU-wide frameworks for specific corporate areas (such as digital sales or contract law) that operate alongside national laws, offering companies an alternative set of rules to choose from.

Member-states have broadly endorsed this agenda, although they disagree on many policy details, and have a tendency to seek to protect their own country’s firms from foreign competition. However, there is a growing recognition that more economic integration is needed; and that if that is pursued without a revamped cohesion policy, it could create further divergence between EU capital cities and poorer hinterlands. So far, EU regional and single market policies have been caught between two objectives, and have managed to achieve both reasonably well. On the one hand, the Union has striven to raise growth for the EU as a whole, by fostering trade integration within the single market. Cohesion policy has contributed to regional growth, but it has performed better in regions that have better measures of governance.27 However, the goal of European policy has also been to help regions that lose out from economic integration. Cohesion policy should always retain this redistributive role, in order to maintain the consensus in favour of open European markets.

But EU policy after the 2024 European elections will have to catch up with two fundamental realities. First, the single market in goods has helped newer member-states converge with West European standards of living. But as GDP growth in Central and Eastern European countries continues to surpass that of many Western European ones, the returns from ploughing even more EU money into their regions will diminish. As noted above, the impact of factors like transport connections on integration in the single market for goods is declining. Moreover, global goods trade has been stagnant in real terms since 2018, with China-US trade wars, Brexit and other forms of protectionism on the rise. Globally – if not necessarily within the EU – the integration of goods production might be reaching its political limit.

Second, services trade has been growing, and much more rapidly than goods trade. This is the fruit of advances in digital technology, cheaper travel and higher demand for tradeable services as economies get wealthier and more complex. Finance, business services, education, marketing, culture and other services can increasingly be delivered remotely. This trend is likely to continue as digital technology progresses.

Services trade provides the next opportunity for growth in Europe, but EU cohesion policy has done little to help it along. Cities – the engines of the services economy – have only been a marginal player in EU funding, despite the efforts by the European Commission to add a stronger urban dimension to cohesion policy. The market in services has also not provided many opportunities for regions that are distant from Europe’s metropolises. There are potentially large opportunities for the European economy in spreading tradeable services activity across more cities – especially those have struggled to find a new role as their manufacturing sectors have shrunk.

4. A city-led strategy to reap the rewards from services trade

Tradeable services are concentrated in cities, especially the largest ones, for reasons of specialisation and agglomeration. The advantages of skilled services workers and their employers in being close to one another has led graduates to move across Europe into major cities.

There are some caveats to this story, though – which creates opportunities for government policy to shift activity into hinterlands, using cities as nodes for production networks that are spread more widely geographically. One challenge is the increased economic and social burdens resulting from traffic delays, overburdened infrastructure and reduced productivity due to the inability of urban systems to keep pace with population and activity growth. Many of the benefits of higher productivity in cities flows to owners of housing and office buildings. More roads and metro lines and other public works can reduce fixed costs – since these do not vary with the number of users once the infrastructure is built – but become more expensive as land values rise. Thankfully, the internet and other forms of digital technology provide opportunities to split up production tasks in the same way as in manufacturing. Examples are Indian call centres, back-office tasks moving to smaller cities and towns, greater use of video conferencing and more remote work.

However, it is unlikely that remote work will lead to a full-blown reversal of centripetal forces. Many are now working in the office two or three days a week because some office time reduces communication costs, provides benefits to career progression and aids supervision by managers. It is expensive and time-consuming to go to the office from hundreds of kilometres away if you need to be there every week.

So what can policy do? European policy-makers at the EU, national and local level should pursue a city-led strategy in two directions. First, policies need to make cities, especially second-tier cities, larger (more populous), by allowing more housing and making it faster to get into the city centre. Adding scale and connectivity increases the accumulation and exchange of human capital, increasing the dividends from the agglomeration effects. But policy-makers should also make cities denser, by allowing more tall buildings in urban cores and improving metro systems, thereby expanding agglomeration benefits and lowering fixed costs. These policies will suck in more workers, raising individuals’ productivity, but add to centripetal forces, with skilled workers and capital shifting into cities.

Policy-makers can at the same time offset these divergent forces by reducing transport times between major cities and surrounding areas. Less dense regions that are near to cities are more productive than ones that are further away.28

Policy-makers can also seek to make cities with lower shares of knowledge workers more attractive to them. This will also provide opportunities to less skilled workers, who can provide knowledge workers with non-tradeable services. Policies to do that include, first, expanding university and technical colleges, and locating nationally significant research and development institutions, such as the European Molecular Biology Laboratory or Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes, and public TV and radio, in cities that need a new economic purpose. Karlsruhe, for example, which excels in the European services trade, is home to the renowned Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), which has helped develop a whole ecosystem of highly competitive and productive services and industrial firms around it. Second, policy-makers should finance urban regeneration to make ex-industrial cities more attractive as places to live in. Third, they should provide more publicly owned housing and adjust zoning laws to provide more affordable housing and ensure less-skilled people can afford to live there.

Many of these policy levers are at the national and local level. So, what should be the EU’s role?

Cohesion policy traditionally faces a trade-off between equality and efficiency – by either providing transfers for regions that lose out or channelling investments into regions to participate in manufacturing value chains. But as manufacturing stagnates and the services sector expands, this trade-off misses the mark. Without change, cohesion policy will increasingly be pushing against the single market’s tendency to turn major cities into services hubs. If EU cohesion policy does not support second and third-tier cities in capitalising on the growth of the services sector, metropolises will be the main beneficiaries.

The EU should adopt a more targeted strategy that reinforces its role in economic growth and puts less emphasis on absolute convergence. A sketch of a strategy follows.

First, the EU should designate three or four large cities as ‘European growth city-regions’ in each of the big countries, and one to two in smaller ones. In almost all cases, national EU capital cities are performing well in services trade. So growth city-regions should be large, ex-industrial cities that can be repurposed for tradeable services. Here picking large cities with the lowest GDP-per-capita is admirable from a convergence standpoint, but it may backfire, because they could lack the characteristics to attract and retain the necessary human capital. Instead, EU and national policymakers should pick cities that are already showing some dynamism and potential in European services trade. For example, in the case of the Germany, Cologne, Karlsruhe and Leipzig are prime contenders; for Poland, Krakow; for Spain a former industrial port city like Valencia; and for a smaller country like the Netherlands, Almere in Flevoland and Utrecht – areas next to Amsterdam, even though both are already doing quite well.

The EU should spend a portion of cohesion funding on these city-regions – ideally by taking money from programmes that do not work well, such as the common agricultural policy, rather than cutting spending to poor regions that show less promise. One key priority is to spend more on transport links between European growth cities and their satellite towns and hinterlands. This would allow the benefits of agglomeration to spread, with workers in surrounding districts having more potential jobs within commuting distance. This would improve matches between employers and skilled workers.

So too would funding for infrastructure that allowed cities to become denser. Just as providing more transport links between cities and their hinterlands expands labour markets, so too does concentrating workers and employers geographically. More water and sewerage, telecoms, metro and bus stops, bike lanes and parks could be funded as cities expand upwards with taller buildings.

Cities tend to be more energy efficient – and have lower emissions – than more sprawling patterns of settlement. But denser cities will need more power, especially as heating, transport and industry are electrified. Data centres need increasing amounts of electricity, too. EU funding can help growth-cities to roll-out district heating systems, electric bus and car charging networks, battery storage and renewable electricity generation more rapidly.

Whenever the EU can locate new EU agencies, R&D or science institutions, they should be in these growth city regions, where practicable. From that perspective, the post-Brexit decision to relocate the European Medicines Agency to Amsterdam and the European Banking Authority to Paris was a missed opportunity. It would have been better to place them in, say, a city like Rotterdam or Krakow.

A city-led strategy also provides opportunities to strengthen administrative capacity, thereby ensuring that EU and national funds are better spent. Regions have struggled to absorb EU funds quickly and direct it towards useful projects. During the last two seven-year EU budget cycles, less than 50 per cent of the EU structural funds committed to eurozone countries were paid out in time, let alone at a faster pace than the ongoing Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which has a six-year deadline.29 The EU should encourage member-states to give growth city-regions a bigger role in managing EU funds, for example to raise the quality of local planning institutions. The EU can also play a co-ordinating role by establishing stronger links between the Commission and growth city-regions, so that knowledge of urban development within the single market can be shared between them.

If the EU budget is reformed, so that less funding flows to farmers and more to growth-enhancing initiatives, it will be important to ensure that some of the money cut from other budget lines flows to growth city-regions. If it is made more conditional on reforms at the member-state level, the EU should demand more administrative capacity for growth city-regions as a price for its cash.30 The RRF provides such a model for the governance of EU funding, even if disbursement was too rushed, so as to comply with a 2026 deadline imposed to allow spending hawks to say that the fund was a one-off.

This is an ambitious and radical programme. But the EU’s growth performance has been weak. Better functioning cities are a sine qua non for higher services trade and productivity growth – it is time for the EU to put services and cities at the heart of its growth strategy.

2: Enrico Letta, ‘Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity: Empowering the single market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU citizens’, European Council, 2024.

3: Christian Odendahl and John Springford, ‘The big European sort: The diverging fortunes of Europe’s regions’, CER policy brief, 2019; Cinzia Alcidi, ‘Economic integration and income convergence in the EU’, Intereconomics, April 2019.

4: Edward Glaeser, Agglomeration Economics, 2010.

5: Stefano Spinaci, ‘Single market barriers report’, European Parliament Members’ Research Service, April 2024.

6: Bertelsmann Stiftung, ‘Estimating economic benefits of the single market for European countries and regions’, 2019.

7: Stephen Reddin and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, ‘Quantifying Agglomeration and Dispersion Forces’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), September 2016.

8: John Bachtler, ‘Cohesion policy - where has it come from? Where is it going?’, European Court of Auditors, 2022.

9: Sacha Becker, Peter Egger and Maximilian von Ehrlich, ‘Effects of EU regional policy: 1989-2013’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2018; Guglielmo Barone et al, ‘Boulevard of broken dreams. The end of EU funding (1997: Abruzzi, Italy)’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2016; Philipp Mohl and Tobias Hagen, ‘Do EU structural funds promote regional growth? New evidence from various panel data approaches’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2010.

10: Richard Baldwin, ‘The great convergence: Information technology and the new globalization’, 2016.

11: European Commission, ‘Annual single market report 2023: Commission staff working document’, 2023.

12: International Monetary Fund, ‘German-central European supply chain – cluster report’, August 2013.

13: Sander Tordoir & Shahin Vallee, ‘Germany needs a new growth model’, CER insight, June 2023.

14: Siyu Huang and Pantellis Koutrompis, ‘European multi-regional input-output data for 2008-2018’, 2023.

15: We use NUTS 2 regional data – this is a territorial unit within the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) used by the European Union for statistical purposes, typically representing a basic region for the application of regional policies.

16: The appendix is published on the CER website separately, see here.

17: The appendix is published on the CER website separately, see here.

18: Siyu Huang and Pantellis Koutrompis, ‘European multi-regional input-output data for 2008-2018’, 2023 and the European Commission’s ‘EU Regional Competitiveness Index: RCI 2010’ & ‘The European Regional Competitiveness Index 2019’. The competitiveness indices from 2013 and 2019 are ‘backward-looking’, recording the state of regional characteristics in 2009/2010 and 2017/2018, aligning with our regional trade data.

19: The appendix is published on the CER website separately, see here.

20: For a summary of the literature on unbundling, see Faezeh Raei and colleagues, ‘Global value chains: What are the benefits and why do countries participate?’, International Monetary Fund, January 2019.

21: Richard Baldwin, ‘The globotics upheaval: Globalization, robotics and the future of work’, 2019.

22: Nathalie Marquez Courtney, ‘Digital tech nomads are pricing Portuguese workers out of the coutry’ country‘, Euronews, April 15th 2024.

23: Andrea Dudik and Daniel Hornak, ‘Eastern Europe is richer than ever – and more divided’, Bloomberg News, April 30th 2023.

24: Enrico Letta, ‘Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity: Empowering the single market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU citizens’, European Council, 2024.

25: Oliver Wyman, ‘The European banking regulatory framework and its effects on banks and the economy’, European Banking Federation, January 2023.

26: Thorsten Beck, Jan Pieter Krahnen, Philippe Martin, Franz Mayer, Jean Pisani-Ferry, Tobias Tröger, Beatrice Weder di Mauro, Nicolas Véron, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, ‘Completing Europe’s banking union: Economic requirements and legal conditions’, Bruegel, November 2022.

27: See footnote 13.

28: OECD, ‘The metropolitan century: understanding urbanization and its consequences’, February 2015.

29: Sander Tordoir and Nico Zorell, ‘Towards an effective implementation of the EU’s recovery package’, ECB economic bulletin, 2021.

30: John Springford and Elisabetta Cornago, ‘Why the EU’s recovery fund should be permanent’, CER policy brief, November 2021.

John Springford is an associate fellow and Sander Tordoir is chief economist at the CER, Lucas Resende Carvalho is project manager, Europe’s Future Programme, Bertelsmann Stiftung

June 2024

This policy brief, a joint project, was written thanks to generous support from the Bertelsmann Stiftung. The authors are grateful to European officials and others who shared their insights into the topic. The views are those of the authors alone.

View appendix

View press release

Download full publication