French lessons for Britain's economy

- Since 2008 Britain’s economy has badly under-performed America’s, but on some key metrics it has also performed much worse than France’s.

- Average wages in Britain are only slightly higher than they were in 2007. That extraordinary fact is down to extremely weak productivity growth after 2008. France, on the other hand, managed to keep pace with US output per hour in the decade after the financial crisis. France’s GDP per capita is similar to Britain’s – and lower than that of the US – because French people tend to ‘bank’ higher productivity by working fewer hours, rather than earning more.

- This policy brief’s analysis of the drivers of British, US and French growth shows that lagging private investment is the main cause of the UK’s growing productivity gap. And contrary to the popular view in Westminster circles – that the biggest constraint on Britain’s growth is that its planning system makes it very hard to build – this paper finds that macroeconomic forces have been crucial. The investment bust after the financial crisis was bigger in Britain than in France, and the UK’s recovery was weaker than in the US. That was true of investment in property, in other physical assets like machinery and computers, and in ‘intangibles’ such as R&D and branding. The vote to leave the EU then snuffed out the investment recovery in all three asset classes.

- These shocks were particularly bad for some of Britain’s exporting industries, compared to American and French ones. Exporters tend to be more productive and an important source of growth in a medium-sized, trade-oriented economy like Britain’s. The UK maintains higher productivity in finance than France, but the gap has shrunk, and the City of London is now less productive than Wall Street. And comparative productivity in manufacturing also dropped after the 2008 financial crisis. Since finance and manufacturing are also badly affected by the trade barriers Brexit imposes, productivity growth in other exporting industries is needed.

- Britain’s professional services and tech sectors offer some cause for optimism: output and exports have performed well since 2016. Productivity growth in the US tech sector has been astonishing, and the gap with the UK is growing rapidly. But Britain’s tech sector productivity has been converging with France’s over the last two decades, and its output has been growing more rapidly. And the UK maintains a big advantage in productivity compared to the US in the professional services sector, which includes accountancy, law, media and scientific research. In these areas, the UK also boasts a big advantage in exports with France.

- The new Labour government’s industrial strategy should focus particularly on professional services and tech. France offers some lessons on how to do so. Unlike the UK, France offers tax relief on investment in intangible assets, like software and branding, which are particularly important to these sectors. France’s denser cities with more extensive public transport provide a productivity boost to professional services and tech firms based there. France’s urban labour markets are larger and more efficient, which helps firms that rely on human capital. Its property tax regime is more proportional to property values, which encourages people to downsize if they no longer need larger houses, helping geographic labour mobility. Higher salary thresholds needed for immigrants to obtain British visas, alongside high visa costs, may also discourage knowledge workers from coming to Britain in the future. And, as a member of the customs union and single market, France has lower barriers to trade than the UK.

- Turning around Britain’s dismal economic performance will be difficult: high interest rates and a tight labour market mean that higher investment will have to come at the expense of consumption, at least in the short to medium term. The reforms outlined in this policy brief will be politically difficult for the British government to enact, and a worsening trade and security environment after Donald Trump’s re-election will stiffen headwinds. But France’s model provides some lessons for Chancellor Rachel Reeves in her mission to raise growth.

The obsession of Britain’s political class with the US, the product of a shared language and the dominance of American culture, means it tends to look across the Atlantic to see how the UK is performing. At present, the comparison is not a flattering one. US growth has powered ahead during the recovery from the pandemic, on the back of large fiscal stimulus and higher investment. Moreover, that comes after Britain had struggled through a prolonged period of weaker growth in living standards than America since the 2008 financial crisis.

The new Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has promised to raise growth, but finds herself in an environment that will make that promise hard to fulfil. Britain’s public debt is high, and interest rates have risen. Labour markets are tight, and sticky inflation suggests there are few scarce resources that she can put to work through fiscal stimulus. Britain has also imposed sizeable trade barriers on itself by leaving the EU, and Keir Starmer has decided not to try to reverse that decision. The security threat from Russia means that defence spending will have to rise, which will require lower government consumption and investment elsewhere. When Donald Trump takes office in January 2025, trade barriers may rise further: he plans to demand better terms of market access for US companies or impose tariffs. A more transactional US will sharpen Britain’s post-Brexit dilemma about whether it should move closer to America, diverging from EU norms and standards in the process, or remain close to the EU, its largest export market.

Britain’s aim should be to ‘muddle through’ the economic risks of Trump, but in the direction of France.

This policy brief compares Britain’s recent economic performance to that of France and the US, and suggests that the successes of France in productivity and investment have been underappreciated across the Channel. Despite the apparent similarities between the US and UK economic models, such as smaller states and larger service sectors than continental European economies, France provides more policies for the British government to consider emulating. France has big economic problems too – slow growth, a sizeable budget deficit and a comparatively low employment rate (although the latter has been improving in recent years). But its workers are more productive, it has a more effective state, and it has made fewer economic policy blunders in the last two decades.

However, what follows is not an argument for Britain to ‘strategically converge’ on the French model. Grands projets are always risky: the last two attempts to reconfigure Britain’s economic and social model have both failed. One of Reeves’s predecessors, George Osborne, sought to reduce the size of the state during a period of weak demand in the 2010s. But he merely weakened growth further and reduced the state’s capacity to deal with shocks like the pandemic. To the extent there was an economic theory behind Brexit – deregulation and free trade agreements with faster growing economies to compensate for higher trade barriers with the EU – it has, predictably, been found wanting, and leaving the EU has imposed huge costs. Instead of radical change, Britain’s aim should be to ‘muddle through’ the economic risks that Trump and Vladimir Putin pose, but in the direction of France.1

The worsening productivity gap with France and America

Britain is often portrayed as a ‘mid-Atlantic’ economy, with a higher consumption share of GDP and a smaller state than continental European countries. It has a more laissez-faire tradition of policy-making, at least since it adopted a floating currency and joined the EU in the 1970s, and Margaret Thatcher’s reforms of the 1980s. And it has been comparatively open to foreign investment, with overseas investors especially attracted to assets located in the engine of the economy in London and the South-East.

Some British economic commentators – especially those of a conservative bent – can be contemptuous of France, with its larger state, more regulated labour market, and higher rates of taxation. It has also found it difficult to curb its chronic budget deficit. In upturns, France’s economic growth rate has tended to be slower than the UK’s, at least between 1993 and 2016, but the UK tends to have larger recessions. As a result, the size of the British and French economies has remained similar for many decades. However, Britain has fallen behind France, as well as the US, on a number of metrics.

“In the long run, productivity is almost everything”, said Paul Krugman – a quote that is almost impossible to exclude from any discussion of the subject.2 Productivity growth – getting more output from labour and capital, and thereby gaining more resources for the same amount of work – matters because other types of economic growth do not raise living standards sustainably. Adding more immigrant workers to the labour force has a small beneficial effect on existing workers’ incomes, but increases living standards less than overall output, because higher national income is shared between a larger number of workers. Juicing growth with fiscal or monetary expansion helps to stabilise output when demand falters, but will lead to inflation and financial instability if used as a long-run strategy. Throwing ever more capital at an economy by splurging on investment in roads, computing equipment and housing ultimately leads to literal and metaphorical bridges to nowhere.

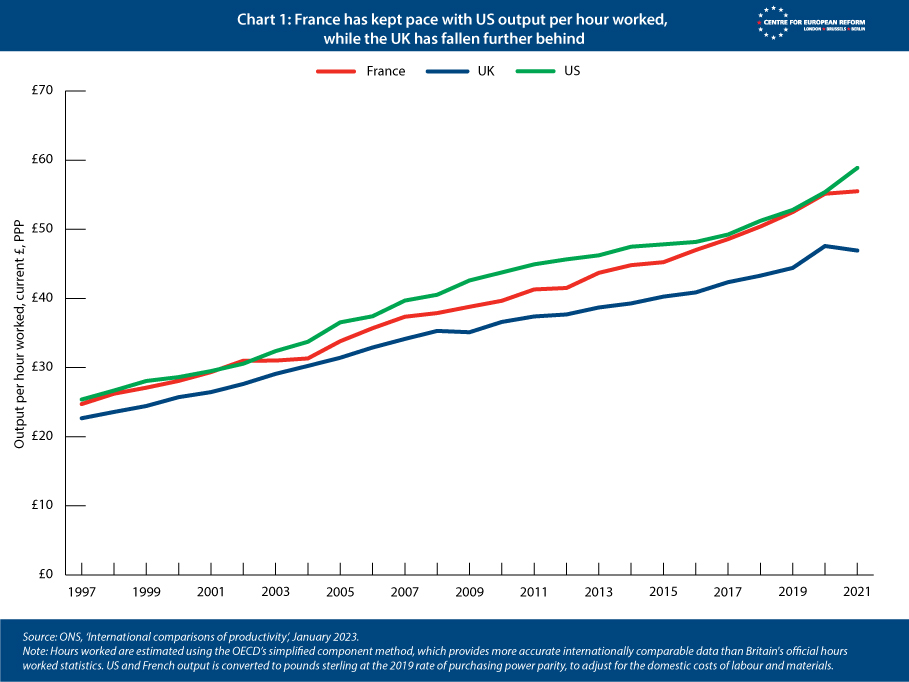

It is well known that US productivity growth has been stronger than the UK’s. Britain’s dismal performance since the global financial crisis is the main reason why average wages have barely improved since then. It is less well known that France’s output per hour worked has been growing at a similar rate to that of the US (Chart 1).

Why, then, is France’s GDP per capita so much smaller than America’s? The answer is that the French choose to bank more of their productivity gains as leisure time than Americans do, with each French worker working about a fifth fewer hours than an American one. Workers in Britain, on the other hand, work more hours than in France but fewer than the US, and are less productive than both.

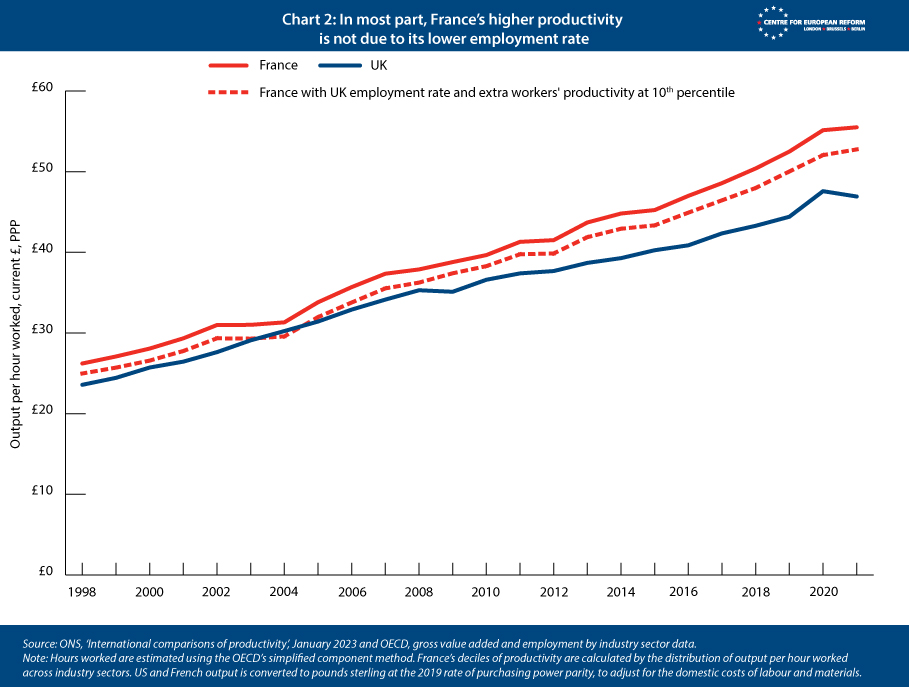

The UK’s productivity gap with France remains even if we account for the fact that fewer French people work. Workless people would tend to be in lower productivity jobs if they were in work, so France’s productivity rate might be flattered by the fact that it has lower employment than Britain does. Chart 2 shows what French output per hour would be if it had the UK’s employment rate, and if all the additional workers were as productive as the bottom decile of French people. In this scenario, France would still be 12 per cent more productive than the UK.

‘Why is Britain less productive?’ is not an easy question to answer. We have limited knowledge about economic development. And what we know can only be formed into vague prescriptions for growth, many of which the UK already follows, such as strengthen property rights, keep corruption to a minimum, strengthen competition – including by remaining open to imports, and divert a decent chunk of revenues to investments that the private sector will underprovide, like education and transport infrastructure. There is no agreed-upon set of policies that governments, if they would only use them, can use to make businesses invest in things that raise output or to help workers be more efficient. And national economies differ from one another because they have different specialisms in knowledge and technology that can be put to work in a globalised economy. ‘Be like France/America’ is not very helpful advice, precisely because they have different economic models but similar productivity levels. And yet, there are some lessons that can be teased out from these countries’ experience over the last few decades.

The problem: private sector investment

The first lesson is that Britain’s weaker growth than France and the US since the financial crisis is largely down to weaker private sector investment in physical capital like buildings, machinery and computers – so-called capital deepening. That contrasts with ‘total factor productivity’ (TFP). These terms tend to make one’s eyes slide off the page, but they are needed to understand why growth has hastened or slowed. Capital deepening means providing more space and tools for workers to use. More capital will raise workers’ productivity up to the point when negative returns set in (a warehouse so crowded with forklift trucks that drivers cannot move around would reduce productivity). Total factor productivity, on the other hand, rises when companies organise capital and workers more effectively, raising their output per hour. It is an amorphous concept, but total factor productivity can rise through better management techniques, ‘learning by doing’ by workers, and improvements in the quality of capital (as opposed to the amount of money invested in capital) such as adopting the latest software.

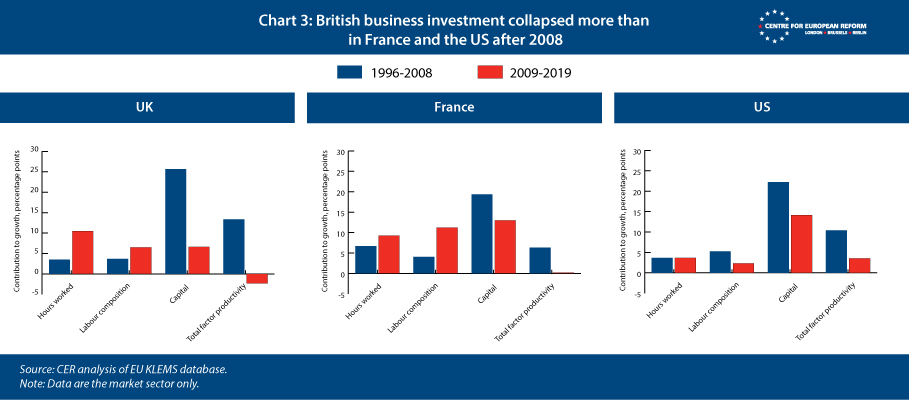

British business investment collapsed more than in France and the US after 2008.

Chart 3 shows the factors driving UK, French and US growth in two periods – the relatively benign conditions of 1996 to 2008, and the dreadful decade that followed. In both periods, France had more rapid improvements in hours worked and ‘labour composition’ – a measure of skill levels – than the UK and the US, but it started from a lower base. However, after 2008 the UK’s biggest problem was the fall in private investment. It contributed more to growth in the good years than in France and the US, and fell by much more in the bad. Total factor productivity did worse than our comparison countries too, but not as badly as capital. In a sense, this is hopeful news. Britain’s problem is not that its line managers became much more incompetent than French or American ones, or that its relative rate of technological progress collapsed, as much weaker performance in total factor productivity would suggest. The problem was that Britons stopped investing. This problem is more tractable for policy-makers: there are more tools for incentivising capital investment than there are for, say, improving managerial competence.

However, we need to understand why capital investment was so much weaker than in France and the US. There are two main theories – structural and cyclical. The structural one is eloquently set out by Sam Bowman, Samuel Hughes and Ben Southwood in a highly cited essay published in September 2024.3 They pin the blame on Britain’s notoriously complex land use planning system, arguing that “higher investment in the UK is mainly frustrated by systems that effectively ban private companies from … building houses, infrastructure, and energy generation”.

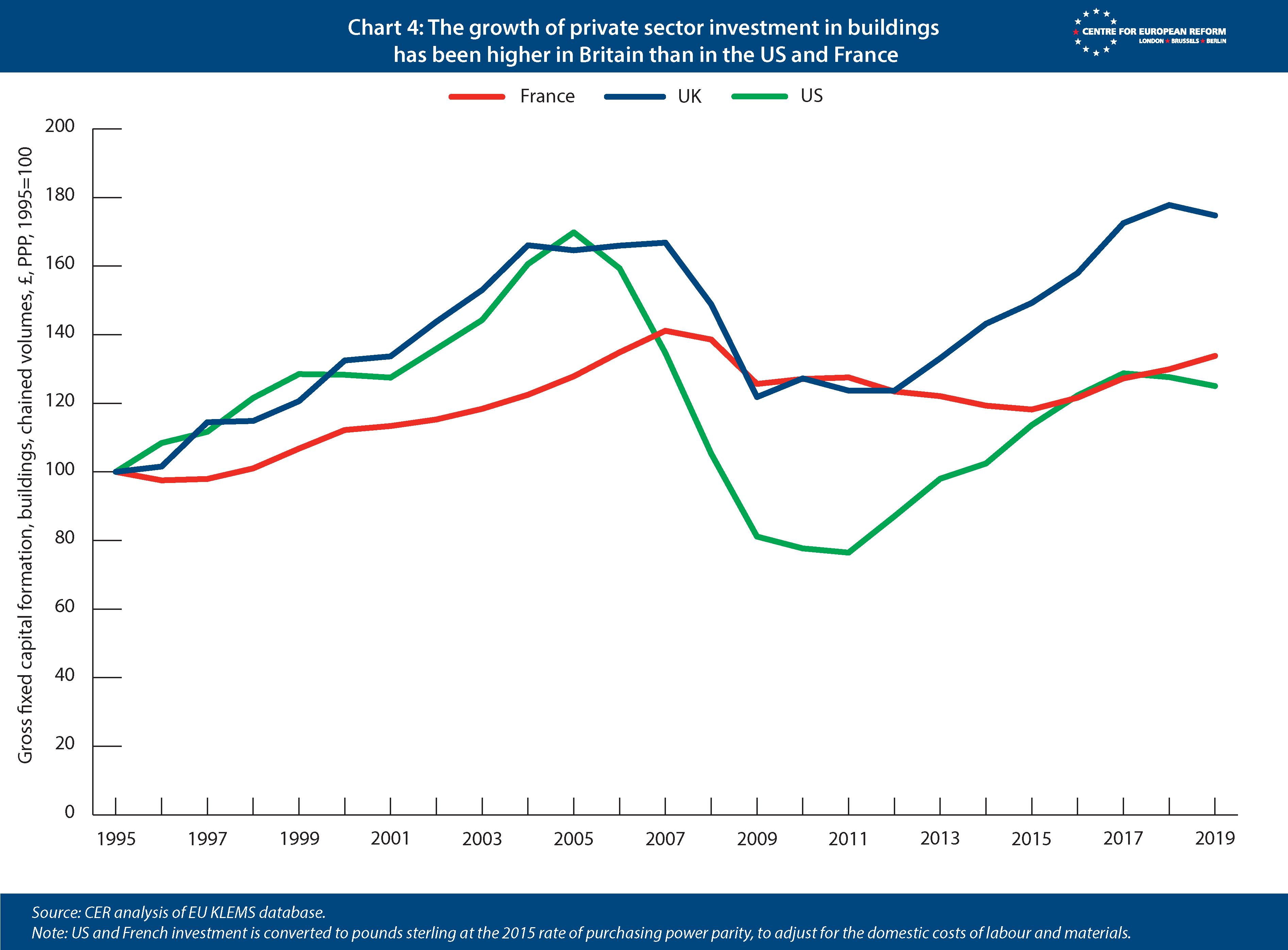

The authors are right that Britain has historically invested less than France and the US in buildings and infrastructure, and its capital stock in these areas is lower. That is reflected in smaller houses, higher congestion and higher energy prices. But they are wrong to argue that the planning system is the main reason why Britain’s productivity growth has stagnated: macroeconomic conditions are more important. Chart 4 compares investment growth in buildings in the three countries between 1995 and 2019. Growth in Britain’s investment in buildings was comparable to the US until the financial crisis, with France stagnating in comparison. During the ‘austerity’ period, when the private and public sectors were retrenching heavily, investment collapsed, before recovering to a level far higher than in France and the US. There was no outbreak of 'planningitis' in 2008-9: instead, financial conditions deteriorated, and public and private sectors cut investment in an effort to curb debt.

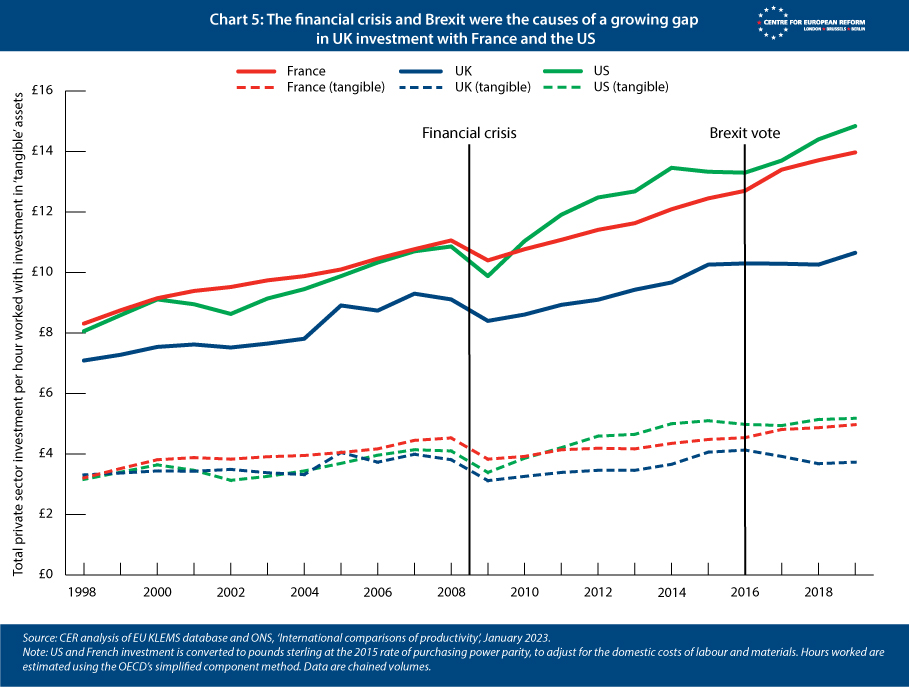

The macroeconomic causes of relative stagnation are even starker if we exclude buildings from a comparison of private sector investment. The gap in investment per hour worked between the UK and the US widened markedly after 2008-9, as the US economy recovered more quickly (Chart 5). And the gap widened with both France and the US after the 2016 vote to leave the EU, which led to a prolonged period of stagnating investment. By 2019, the UK was investing about a quarter less than both other countries. The cyclical nature of investment divergence is particularly noticeable in ‘tangible’ assets, marked by the dotted lines on Chart 5. This is investment in physical stuff – computers, machinery and so forth – as opposed to intangible assets like R&D, branding, software and intellectual property. These sorts of investments are ‘lumpy’ durables that are often financed by borrowing – and can be patched up towards the end of their life to keep them going, rather than splurging on new kit. After a recovery between 2009 and 2016, investment in tangibles then fell back with the prospect that Britain would leave the single market and customs union.

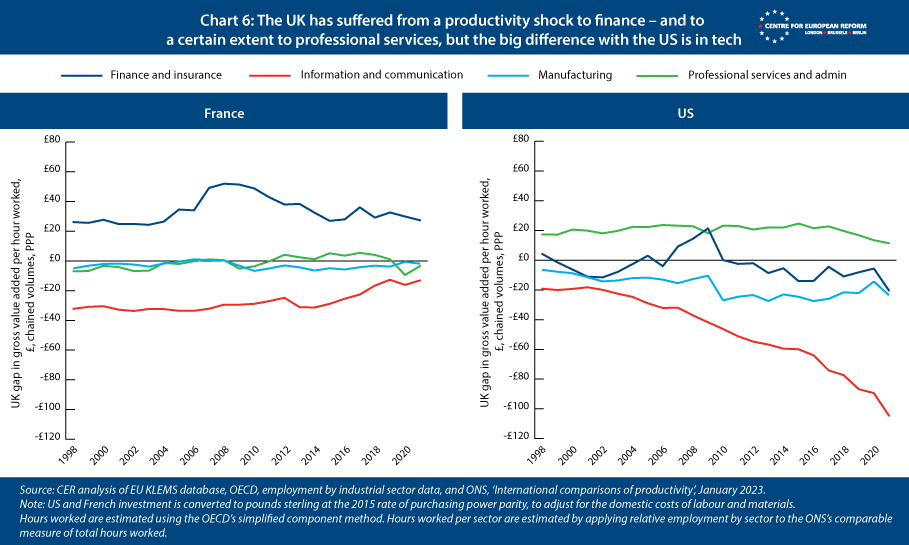

Might the cause of weak private sector investment be that the UK has been particularly buffeted by shocks to certain industries that it has an exporting advantage in? For a comparatively small, open economy such as the UK, productivity growth is led by exporting sectors. That is the case to an extent: Chart 6 shows the gap in output per hour worked in key exporting sectors between the UK and France/the US. In financial services, the 2004-8 bubble burst, and the UK’s higher productivity in that sector fell markedly. In manufacturing, the gap in productivity with both countries worsened after the financial crisis. And after the Brexit vote, Britain’s high gap in professional services productivity has been eroded vis-à-vis the US and France, probably because London was no longer such an effective base for professional services firms outside the single market. On the other hand, the UK is building a more productive tech sector, closing the gap with France: tech is relatively unaffected by the trade barriers with the EU that the post-Brexit trade deal has imposed. As shown below, output and exports have been growing in that sector rapidly, too. But, given that the giants of the tech sector are largely US firms, several of which have entrenched positions in their respective markets, US investment in that sector has streaked ahead.

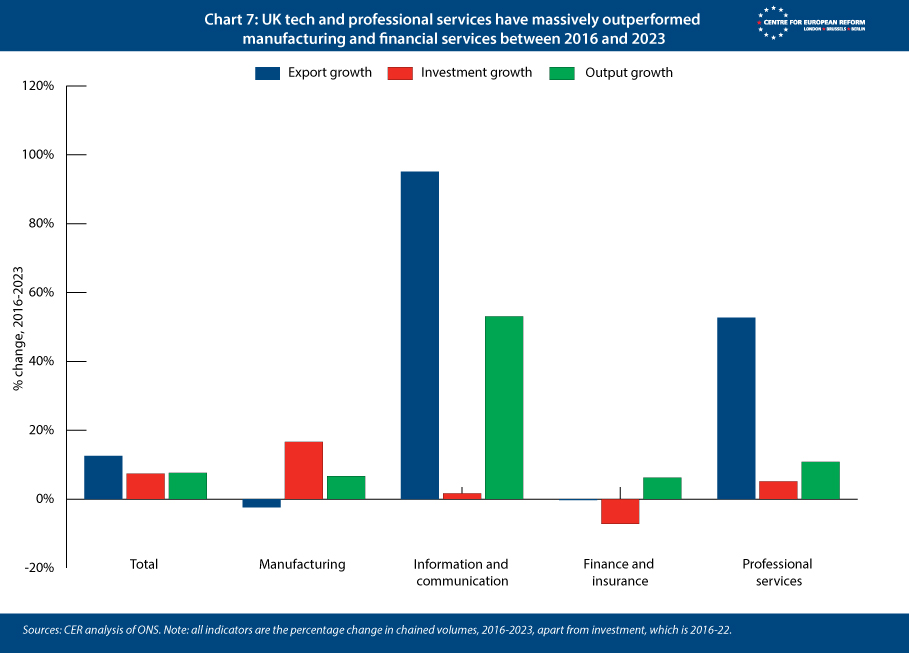

These trends suggest that Britain’s most promising ‘knowledge services’ – tech and professional services – should be at the centre of the Labour government’s new ‘industrial strategy’, rather than stagnating sources of export earnings: manufacturing and finance. Since 2016, export and output growth has been much higher in ICT and professional services than in goods production (Chart 7). These sectors’ growth is less dependent on high levels of capital investment than manufacturing, because human capital is more important than physical to the production process. Goods output and exports have struggled since 2016, unsurprisingly, given the high barriers to goods trade with the EU that the EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement imposed. For the same reason, financial services export growth since 2016 has been zero, and disinvestment in the sector is continuing. Finance exports have also significantly underperformed the OECD average since the UK left the single market in 2021.4

An industrial strategy for straitened times

The Labour government’s industrial strategy white paper, sensibly, includes life sciences, tech, professional and business services and creative industries in its ‘eight growth-driving sectors’ that will be the focus of government support.5 The final plans are still being put together, so some broad suggested principles for the strategy follow.

First, investment is a cost to consumption when an economy is at full employment and interest rates are higher than zero. The UK has high investment needs, not just because of the shocks of the 2010s, but also because its infrastructure has been increasingly congested for several decades, and net zero targets will require more private and public sector investment. Higher rates of investment in public services and infrastructure will require workers to be shifted from other sectors of the economy, including consumer-facing services like retail and distribution – and, potentially, housebuilding. Regulation, road pricing, and higher user charges are needed to push private sector investment in infrastructure up, but the higher relative prices and interest rates that will ensue will eat into consumption, at least in the short to medium term. Reeves was perfectly justified in borrowing 1 per cent of GDP for higher government investment to improve public services and transport, but that will entail higher interest rates, which will in turn mean curtailed household consumption to pay for higher monthly mortgage payments. Trading some consumption now for higher growth in the future is sensible but it is challenging politically, and ensuring that investment is efficient is critical.

That means that industrial strategy should focus on the sectors that will drive the most output and export growth for the least capital investment. Business services, like accountancy and consulting, require lower investment in both tangible and intangible capital for any pound of output than life sciences and tech, and lower ratios still than manufacturing and clean energy. Helping dull lawyers, accountants, media executives and advertisers to grow their businesses is as important to economic growth as encouraging more flashy data centres, supercomputers or scientific labs.

Trading some consumption now for higher growth in the future is sensible, but politically challenging.

Second, the need to economise on ‘building physical stuff’, given the country’s transport, energy and water construction needs, means that the government will have to be selective. There are only so many people who are willing to work in construction, and imported materials need to be paid for. The government’s plans to reform the planning system is welcome, but building more housing estates that are poorly connected to city centres will not raise productivity. High-rise, denser cities are more capital and energy efficient, and they allow people easy access to more jobs. The costs of transport to and from work, for the government, the individual, and the environment are also lower in cities, especially with infrastructure that helps people to walk and cycle.

Third, tax reform is an important tool to raise investment and make it more efficient, and Reeves largely ignored that in her first budget, apart from making tax relief for investment in tangible assets permanent (her predecessor, Jeremy Hunt, had introduced the relief but on a temporary basis). Road pricing will reduce congestion, curbing the cost of building new roads and maintaining old ones (revenues from the current system of fuel duty and vehicle taxation will fall as the country shifts to electric vehicles). By updating property valuations – last conducted in 1991 – to ensure tax is more proportional to current values, the Chancellor would encourage existing housing to be used more efficiently, as older occupiers of family houses would move to smaller homes to reduce their tax bills. Eliminating stamp duty, which is in effect a tax on moving house, would also help.

Fourth, maintaining openness to imports and immigrants – and, if possible, becoming more open – will help reduce the consumption costs of higher investment. With its small manufacturing sector and limited natural resources, the UK imports most of the physical resources that fulfil its investment needs. Trump’s victory will impose several invidious choices. If he goes ahead with his plans to impose a 10-20 per cent tariff on imports from the UK, the government will have to decide whether to accede to his demands for more market access or to impose retaliatory tariffs on US imports. As the UK is no longer a member of the EU customs union, it does not have the strength in numbers that the EU provides – its market is smaller, so the relative costs that it can impose on the US via tariffs is lower.

What is more, Trump may pressure the UK into imposing high tariffs on Chinese goods too – he is planning a 60 per cent tariff on imports from China. China provides more than a tenth of Britain’s goods imports, and higher tariffs would raise the cost of key materials needed for the energy transition, especially batteries and electric vehicles. Unless Starmer is willing to violate his red lines and take the UK back into the single market and customs union, maintaining the UK’s current level of openness to imports – already diminished by leaving the EU – will be difficult. Britain has a smaller manufacturing sector than the EU, which means it has weaker domestic interests pushing for protection, which might help the government to withstand US pressure.

Finally, so far, the government has not announced plans to change the immigration system they inherited from the Conservatives. After net immigration rates surged after the pandemic, the Conservatives raised the low salary thresholds that immigrants must fulfil to take a job in the UK (with some exceptions in health and social care). High visa costs, and the ‘immigration health surcharge’ – which is, in effect, a £700-1,000 annual tax on visa-holders – may make the UK less attractive to immigrants as the post-pandemic surge subsides, especially those from other rich countries. There is a risk that an industrial strategy founded on knowledge services conflicts with an immigration system that imposes high barriers on skilled workers entering the country. If it is serious about its growth mission, the government should reduce disincentives to immigrate.

Muddling through, but towards France

France already fulfils many of the principles set out above. It has a somewhat larger manufacturing sector than the UK, but it also has strengths in finance, professional services, tech and life sciences. These high-skilled services jobs are more concentrated in France’s largest cities than in the UK’s, which is probably because French cities are denser, and its transport systems are more extensive and less congested.6

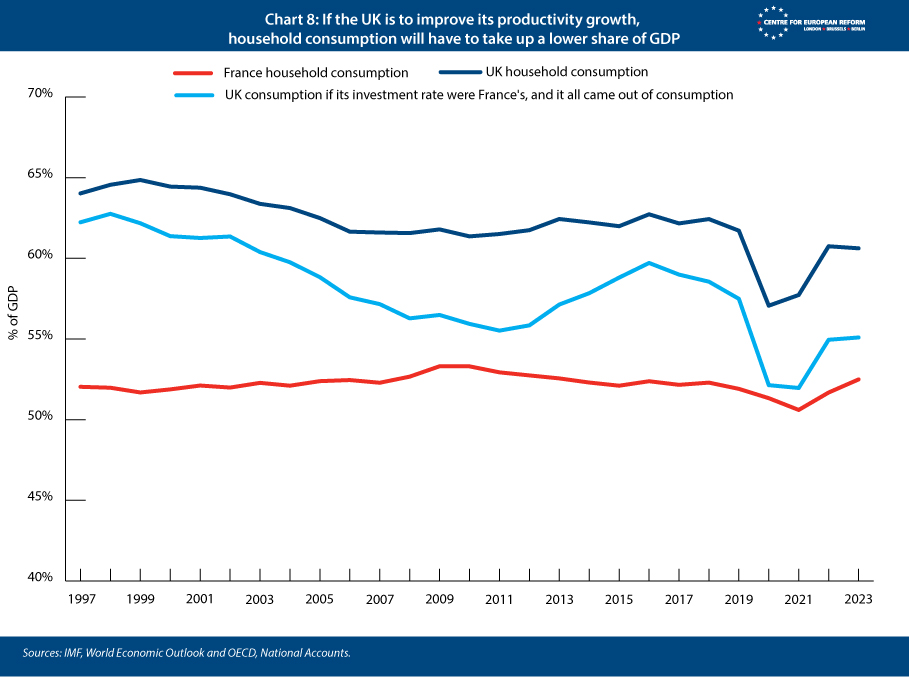

France’s investment rate is significantly higher than the UK’s, and that comes at the cost of lower household consumption, which makes up about 52 per cent of GDP in France, and 60 per cent in the UK (Chart 8). If the UK had managed an equal public and private investment rate to France in the past quarter century, instead of sweating its depreciating assets, its household consumption would have been similar. This is not an unreasonable guide to Britons’ future, given the limits to the UK’s ability to borrow to invest now that interest rates have risen. The US, given the exorbitant privilege of the dollar, the size of its market, and its investment system, is able to run larger deficits in order to pay for investment. Britain should prepare for weak consumption growth if it is to improve its capital stock.

France also has a tax system that does more to encourage investment than the UK does. It has a wider range of investment costs that are eligible for tax breaks than Britain’s Treasury provides. The UK’s ‘full expensing’ system, which Reeves made permanent in her budget, largely provides tax benefits to tangible capital like machinery and buildings.7 France provides tax breaks for a broader range of intangible assets, including software and branding, which are more important for Britain’s most promising sectors.8 France also has more toll roads than the UK, reducing congestion. It has more progressive property taxation than the UK does, which is more closely linked to property values.9 Local governments have more power to raise taxes to pay for improvements to public transport than in the UK, which explains why its metro, tram and bus systems are much more extensive. The biggest inefficiency in France’s tax system is high payroll taxes, which discourage hiring and contribute to France’s high structural unemployment rate. But this system does appear to provide stronger incentives to invest than the British one: and in part, investment in capital becomes more attractive when labour costs are higher.

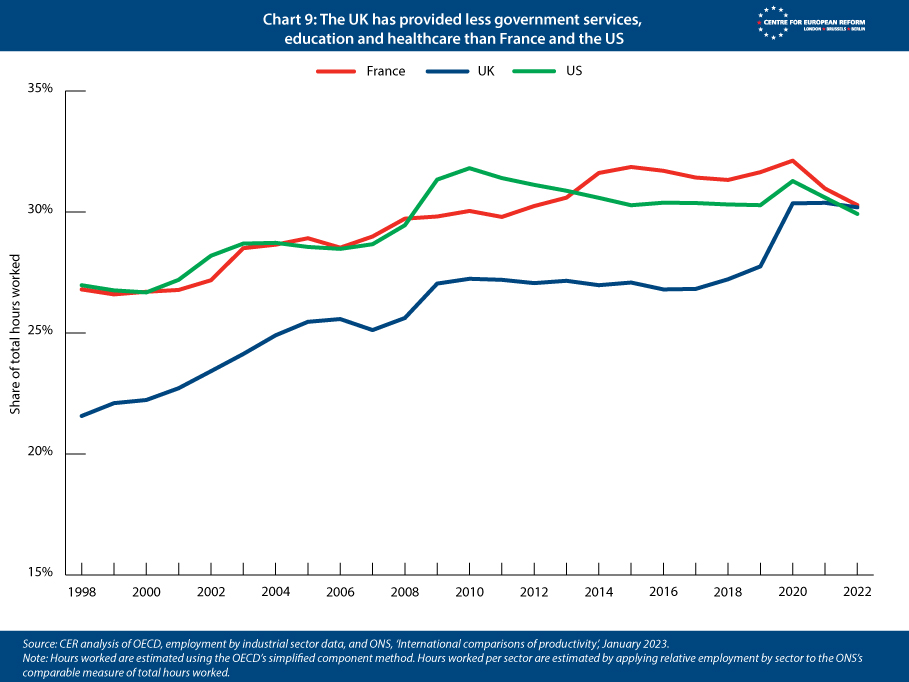

France’s state is also far more efficient than that of the US: less of its national income is gobbled up in healthcare and education costs, and more is freed for investment to increase productivity. The common assumption is that Britain sits somewhere between France and the US in the provision of government services, education and healthcare. Healthcare is privately provided in France (though paid for by mandatory insurance and subject to government price control) and similarly in the US (but with far less comprehensive coverage and few price controls). But in reality, the UK has historically put fewer resources into these services than France and the US, as shown by its lower share of total hours worked in public services (Chart 9). The difference is that the US system for providing healthcare is extremely inefficient. The US spent $12,500 per head on healthcare in 2022, compared to $6,600 in France and $5,400 in Britain, but the life expectancy of its citizens is several years lower.10 After the pandemic, hours worked in the UK public sector jumped. But long waiting lists in healthcare got worse, and continued growth in school class sizes and a slow criminal justice system mean that Reeves plans to spend significantly more in these areas than the Conservatives planned. So a bigger UK state is here to stay – and an ageing population means that more resources will have to be put into health and social care over time.

Healthcare spending pressures make public investment choices difficult. To her credit, in her October Budget Reeves committed to maintain higher public investment rates in the UK. These rates have been converging on French and US levels since Boris Johnson’s tenure as prime minister. But the lion’s share of the investment went to healthcare and education, and transport investment will fall by 3 per cent next year.11 Better urban transport will be needed in future years if the UK is going to improve the laggardly productivity levels of its major cities, and by extension its most promising sectors: tech and professional services.12

France has a major advantage over Britain in maintaining openness to trade: it is a member of the EU. That may help it to navigate Trump’s trade wars more easily, because retaliatory tariffs by the EU as a whole pose more of a threat to the US economy than Britain can muster alone. It remains politically unlikely that Britain will reverse the costly decision it made in 2016, given the trauma that the Brexit period inflicted – and the wasted government time as problems were mounting. But the new Labour government does have the power to help advance a high-skilled services model that was already in train in Britain, and that Brexit will inevitably hasten.

The fact that services trade remains such an advantage for the UK will also help as goods trade wars rage. But Britain will have to find a way to direct more resources into investment, trimming consumption, in order to raise growth. And there will be strong headwinds, with geopolitical and trade instability looming.

Conclusion

To finish with some political conclusions: any attempt to rapidly reverse scars of the economic shocks and policy blunders of the last fifteen years will probably fail. Reeves’s strategy of raising taxes and borrowing was largely vindicated, with no financial market revolt, despite the fact that she was planning to borrow nearly as much as Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss did in their infamous 2022 mini-budget. However, the market reaction did show that a rapid turnaround will be difficult: interest rates and inflation are forecast to be a little higher as a result of additional government borrowing. Public investment will be maintained at a level slightly below France and the US, rather than exceeding it in order to make up for the underinvestment of the last decade. The Chancellor may still get lucky with faster-than-forecast growth improving the public finances. But weaker trade and the need for more defence spending after Trump’s victory have surely diminished Britain’s economic prospects.

What is more, opponents of reforms that would raise investment remain powerful. Policies to raise growth are painful, because they push labour and capital to shift to more productive activities, which many workers and businesses will oppose. Higher investment means lower consumption in an economy that is at full capacity. If the government were to rapidly pull all the levers available to raise private sector investment – tax and planning reform; forcing up infrastructure investment and allowing higher user charges to pay for it; reversing Brexit; higher immigration and higher tax for higher public investment – it would risk a political revolt. Rebuilding Britain will be the work of at least two terms. Muddling through the storms of Trump’s presidency, but slowly proceeding towards the high-investment and high-productivity model of France, seems to be the ‘industrial strategy’ with the most chance of success.

2: Paul Krugman, ‘The age of diminished expectations: US economic policy in the 1990s’, MIT Press, 1994.

3: Sam Bowman, Samuel Hughes, Ben Southwood, ‘Foundations: Why Britain has stagnated’, ukfoundations.co, September 2024.

4: John Springford, ‘Brexit, four years on: Answers to two trade paradoxes’, CER insight, January 25th 2024.

5: Department for Business and Trade, ‘Invest 2035: The UK’s modern industrial strategy’, October 2024.

6: Kathrin Enenkel, ‘Why large French and German cities perform better than their British neighbours’, Centre for Cities, August 2021.

7: Paul Brandily and others, ‘Beyond boosterism: Realigning the policy ecosystem to unleash private investment for sustainable growth’, Resolution Foundation, June 2023.

8: PwC, ‘Worldwide tax summaries: France’, March 2024.

9: Alexander Leodolter and others, ‘Taxation of residential property in the euro area with a view to growth, equality and environmental sustainability’, European Commission, 2022.

10: OECD, ‘ Health spending’, 2022.

11: HM Treasury, ‘Autumn budget 2024’.

12: John Springford, Sander Tordoir and Lucas Resende Carvalho, ‘Why cities must drive growth in the EU single market’, CER policy brief, June 20th 2024.

John Springford is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

December 2024

View press release

Download full publication