European common debt: Is defence different?

- The proliferation of threats to European security has forced European countries to increase their defence budgets. But filling long-standing gaps in military capabilities will take time, a sustained fiscal effort and better co-ordination of national military spending.

- Efforts to strengthen defence capabilities are largely national, but the EU is playing a growing role in some areas – such as fostering joint research. Now, constraints on national budgets are pushing European policy-makers to consider innovative ways to boost and co-ordinate defence spending.

- The notion of EU defence bonds is routinely touted by European leaders.

- Defence bonds have three key selling points:

- They would increase overall European defence spending.

- They could enhance efficiencies through pooled investments, generating economies of scale.

- They would also reduce free-riding by some member-states who have been reticent about increasing defence investment.

- Defence bonds could be used to fund several European public goods:

- To support Ukraine.

- To enhance European defence R&D and production.

- To encourage joint procurement.

- To finance efforts to strengthen borders and critical infrastructure.

- Defence bonds face three main hurdles:

- Opposition to joint debt in principle by a group of wealthy, fiscally hawkish countries.

- Differing threat perceptions between member-states and concerns about sovereignty and neutrality.

- Distributional questions about which countries – and which defence industries – would benefit from higher defence spending.

- In terms of design, options for defence bonds include using existing EU funding mechanisms, creating a defence-specific fund, or establishing a new off-budget instrument. Each option has advantages and challenges, particularly regarding their legal and political feasibility.

- For defence bonds to be viable, additional national guarantees would be required, especially since existing commitments in the EU budget limit the Union’s borrowing capacity. The European Stability Mechanism provides an alternative model, but it would require an institutional overhaul.

- Defence bonds face significant obstacles. Yet, as threats to European security grow, the lure of innovative defence funding solutions may prove irresistible. If designed carefully, EU defence bonds could offer the financial firepower necessary to close capability gaps and strengthen European deterrence.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine upended European security. The war shows no sign of winding down, and the threat of Russian aggression is likely to endure even if the conflict ends. As Americans head to the polls to elect a new President, Europeans also fret about Washington’s weakening commitment to their defence. A Trump presidency threatens to weaken NATO and undermine deterrence, but even if Kamala Harris wins, Europeans will need to do more for their own defence, as the US will have to devote additional resources to countering China’s military build-up in Asia.

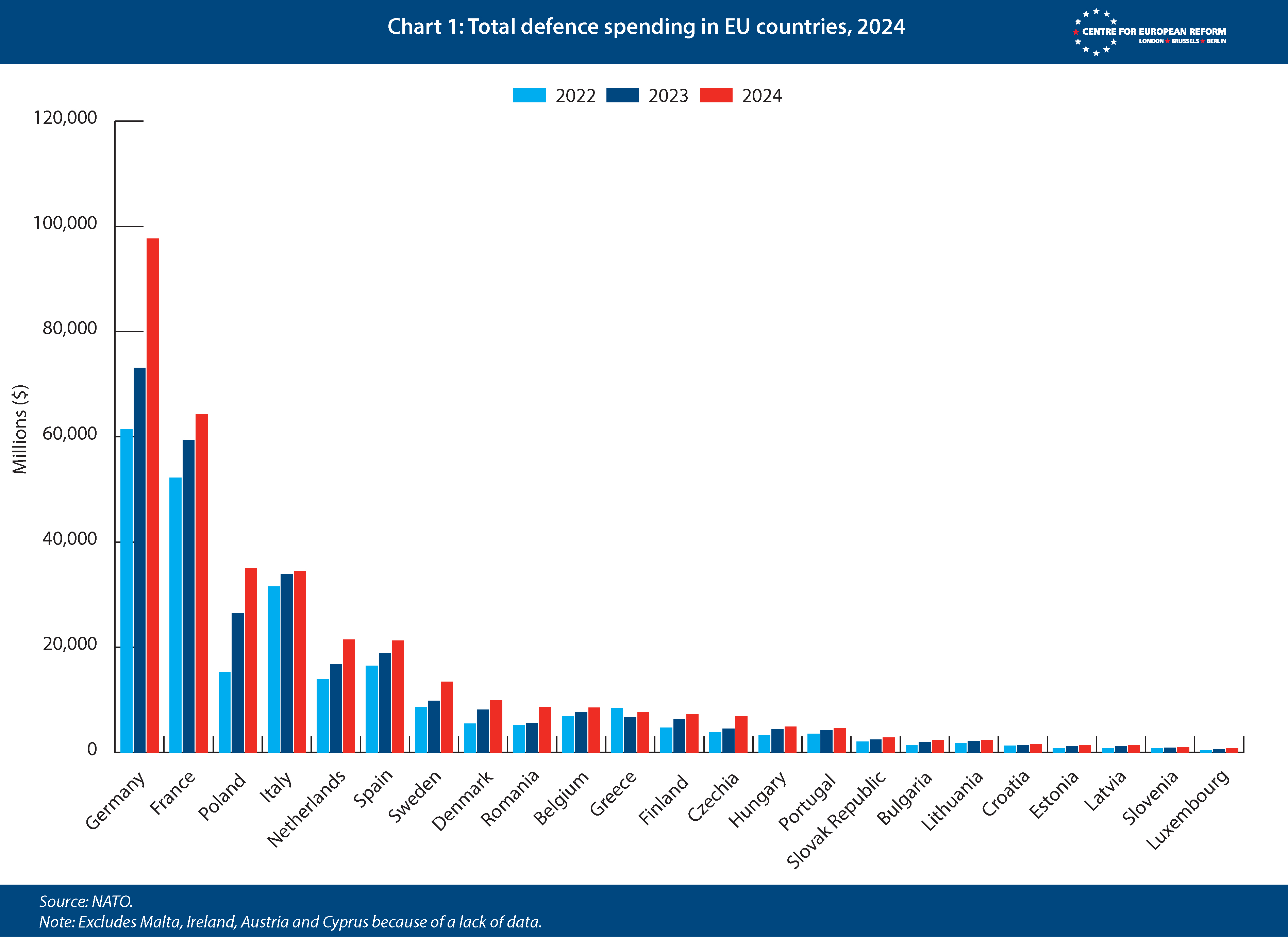

The proliferation of threats has led Europeans to raise their defence budgets substantially in recent years. As can be seen in Chart 1, some EU member-states are rapidly ramping up defence spending. Sixteen of them are due to spend over 2 per cent of GDP on defence this year.1 However, the under-investments in defence over the past three decades mean that it will take many years to fill the capability gaps that Europeans face in a range of areas from ammunition to precision-strike weapons. According to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the EU needs €500 billion in additional defence investment in the coming decade.2

European policy-makers are looking for new financial tools to strengthen their defences.

At the same time, there is a growing emphasis on spending in a more co-ordinated way, to improve the interoperability of military equipment and address the fragmentation of Europe’s defence industrial base, which remains largely organised along national lines and therefore hinders economies of scale. European defence innovation is also lacking: as the recent report by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi highlights, EU members spent only 4.5 per cent of their defence budgets on R&D, totalling $11.8 billion, while the US spent $138.9 billion in 2023, amounting to 16 per cent of its $847 billion budget.3

Funding European defence is a major challenge. Private financing of defence is scarce and the sector has long suffered from a poor image amongst investors, although the tide may be turning. Valuations of publicly-traded European defence companies, as measured by an index of aerospace and defence stocks, have approximately doubled since February 2022, far outstripping the performance of the broader European market. But these valuations, and the availability of private credit for defence more generally, will be contingent on demand for defence capabilities, which will always remain driven by governments.

Public financing is therefore essential to boost the EU’s defence capabilities. But in many member-states, it is unclear whether political consensus for raising defence budgets in inflation-adjusted terms will be sustained in the future. Voters are unlikely to support higher defence expenditures if these are perceived to come at the expense of higher taxes or lower spending on other priorities. Faced with these challenges, European policy-makers are looking for new financial instruments to enhance their defences.

One proposal is the creation of EU defence bonds. Ever since the Union’s pandemic recovery fund made large-scale common EU borrowing a reality, policy-makers have often looked to such an instrument as a solution for a range of problems. But defence is exceptionally intertwined with member-states’ national sovereignty, and the EU’s role in defence is still embryonic.

This paper explores the case for defence bonds and the potential models for their design, as well as the challenges that must be addressed if they are to become a viable tool in the EU’s security strategy.

The EU’s involvement in funding defence

The overwhelming majority of defence spending in Europe is done through national budgets. However, the EU has in recent years emerged as a sizeable actor, in particular since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although the EU budget cannot legally be used to fund “expenditure arising from operations having military or defence implications” (Article 41.2 TEU), member-states have found other ways to fund defence jointly, particularly by leaning on the Union’s competences in the field of industrial policy (Article 173 TEU). The European Commission is supporting co-operative defence R&D activities through the European Defence Fund (EDF), which is worth almost €8 billion between 2021 and 2027, and is aimed at strengthening the competitiveness of the EU’s defence industry.

The EU budget is also being used to fund the expansion of ammunition and missile production through the €500 million Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP), and to foster more joint procurement through the €310 million European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA). While both tools are small in size, they are due to be expanded in the planned European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP), currently under negotiation. Separately, the EU has used the off-budget European Peace Facility (EPF), now worth €17 billion, to reimburse member-states for some of the equipment they have given to Ukraine, and to strengthen Ukraine’s defence industry. Meanwhile, the Connecting Europe Facility, which is designed to fund the development of transport infrastructure, is providing €1.7 billion in the current EU budget to strengthen ‘dual-use’ infrastructure that serves both civilian and military purposes.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is also increasingly involved in defence. Traditionally, the EIB has excluded ‘pure’ defence from its activities and applied a high threshold to financing dual-use goods, only funding projects deriving 50 per cent or more of their expected revenues from civilian uses. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EIB launched a Strategic European Security Initiative (SESI), providing €8 billion in financing for dual-use goods until 2027.4 In January this year, the EIB’s European Investment Fund launched a €175 million Defence Equity Facility (with €100 million coming from the European Defence Fund). The Facility is meant to support small and medium-sized defence enterprises (SMEs) and defence start-ups. And in May, the EIB changed its lending criteria, waiving the requirement that dual-use projects need to derive 50 per cent of their expected revenue from civilian use.5

Towards EU defence bonds?

The growing emphasis on co-ordinating defence spending, combined with constraints on national budgets, has sparked a search for other forms of funding – including EU defence bonds. At the June meeting of the European Council, EU leaders tasked the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, and the Commission with presenting options “for public and private funding to strengthen the defence technological and industrial base and address critical capability gaps.”6

The taboo over EU joint borrowing was broken during the Covid-19 pandemic, when member-states agreed to establish a €800 billion Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which provided a mix of grants and low-interest loans to individual EU countries. Some are now advocating a repeat of the experiment for defence. France and Estonia were the original proponents of defence bonds early this year, but the idea has since gathered support from other members, including Italy, Spain and Poland. Conversely, Germany has argued that its hands are bound by its national constitutional court ruling stating that the RRF was a one-off.

Separately, the report on the future of the single market issued by former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta proposes using the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to issue low-interest defence loans to member-states.7 The ESM was established during the Euro crisis and is the eurozone’s permanent rescue fund. It was originally set up as an inter-governmental organisation outside the EU’s legal framework in 2012, to provide loans to financially distressed countries.

Is there a case for EU defence bonds?

In theory, there are a range of potential uses for defence bonds:

1) To support Ukraine by funding weapons purchases, whether from the EU, from other countries and/or from Ukraine’s own defence industry;

2) To boost production of defence equipment in the EU or bring down funding costs for defence firms;

3) To help finance research and development of next-generation military equipment;

4) To help fund the joint procurement of specific military capabilities such as air and missile defence;

5) To fund dual-use infrastructure and measures such as the upgrading of critical civilian infrastructure to make it more resilient, and to finance border defences such as anti-tank obstacles in countries bordering Russia.

EU defence bonds have the potential to address three key obstacles to strengthening European defence.

First, defence bonds can raise aggregate defence spending. EU countries with relatively high debt levels, or whose debts are perceived as risky, have higher borrowing costs than the EU (or the ESM) as an issuer. They may therefore under-invest in defence. Some member-states on the EU’s eastern border – like Finland and Estonia – have relatively low debt levels and can finance their government expenditures at lower interest rates than the EU average. However, the rates paid by other countries, such as eurozone countries Lithuania and Latvia, and Bulgaria and Romania (which are not yet in the euro) are higher than the EU average. Italy, Spain and other high-debt countries further removed from the border with Russia also stand to benefit. These countries would be able to invest more in defence if they drew on EU debt, as it could bring down their cost of funding.

Second, as Draghi argues in his report, the fragmentation of defence R&D and procurement spending into relatively small national programmes leads to inefficiencies and duplication. It also makes it more difficult to launch large, capital-intensive or high-risk projects. If directed at commonly agreed priorities, defence bonds would therefore enable joint spending that would provide more bang-for-the-buck in terms of defence capabilities. It would also be easier to overcome collective action problems and realise large projects of common interest, like improving air defences for the continent at large, which may not materialise if member-states have to wrangle for years about what equipment to buy, or their workshare.8 An additional advantage of defence bonds is that they could allow for more predictable multi-year project-funding, unlike national budgets which are more volatile.

Third, defence bonds would help address the issue of free-riding. A member-state that strengthens its military capabilities also benefits others. Poland’s large defence investments, for example, also increase security for its neighbours. Despite this, there is a temptation for each member-state to free-ride on the defence capabilities of other European countries (as well as of the US). Chart 2 shows large divergences in the recent evolution of defence spending. Mutualising some defence spending through defence bonds would spread the burden across member-states, and align incentives better. Countries with little inclination to invest in defence themselves would contribute to strengthening European security via their contribution to the EU bonds.

In theory, the EU budget could be modified to funnel more money into funding defence, for example by increasing the budget for EU defence programmes. However, fundamental reform of the budget has repeatedly proved politically impossible. The strongest backlash against budget reform has come from poorer regions or their national governments, which heavily rely on cohesion funds, and from the agricultural sector, which relies on money from the Common Agricultural Policy. Defence bonds offer an alternative.

However, there is also considerable opposition to the idea of defence bonds. First, a group of wealthy, fiscally hawkish countries opposes joint debt in principle, insisting that the EU debt issuance for the pandemic recovery fund was a one-off. Second, there are political hurdles in the form of differing threat perceptions and scepticism about greater EU defence spending in neutral member-states. Threat perceptions across Europe are not uniform: it will not be easy to persuade countries that are far away from Russia and do not feel they need to spend much on defence to agree to defence bonds. Similarly, the idea of mutualising (parts of) defence spending, let alone doing so through EU debt, could be a difficult sell to neutral member-states and to eurosceptic voters.

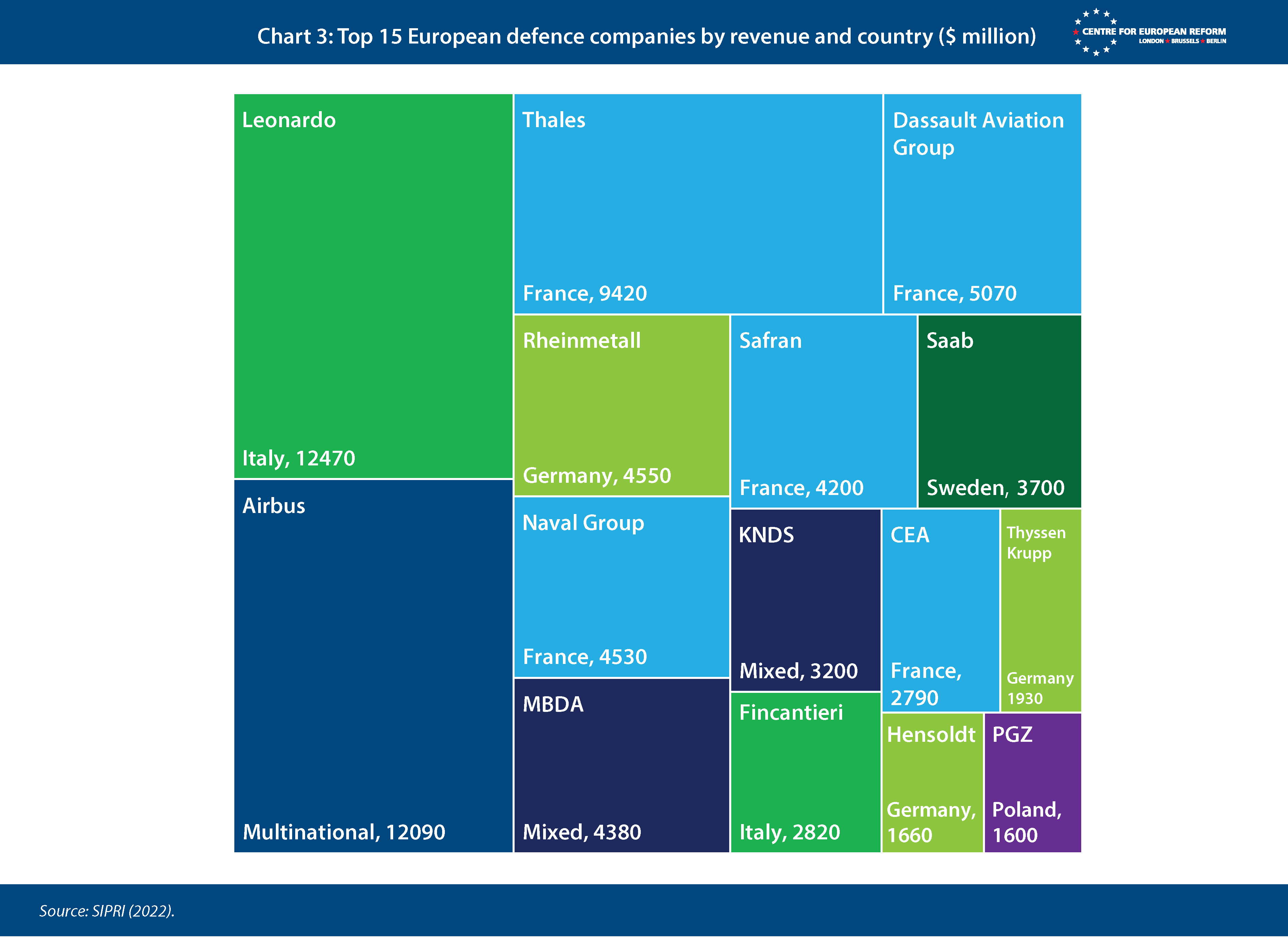

Third, there are challenges related to who would benefit from defence bonds. The biggest European defence companies tend to be in the largest and most industrialised countries, as can be seen in Chart 3. Large member-states with big defence industries, like France, will try to insist that funds raised through defence bonds should be channelled exclusively or near-exclusively to EU firms. Meanwhile, countries without large defence industries of their own have little incentive to adopt such buy-European provisions, as they may wish to use money to buy primarily from outside of the EU to fill capability gaps quickly.

These challenges are not insurmountable. A Trump presidency and a change of government in Germany, combined with a rapid Russian advance in Ukraine, could persuade many countries that increasing defence spending is urgent – and that defence bonds are a good way to do that, after all. In some countries, the public may accept higher defence spending more easily if this is done co-operatively rather than at a national level. It may be possible to structure defence bonds in a way that excludes unwilling member-states, for example by granting neutral countries an opt-out. It should also be possible to design defence bonds so that all member-states will feel they can benefit. For example, defence bonds could focus on only a few defensive priorities such as improving air defences and supporting Ukraine. Defence bonds could also fund a mix of off-the-shelf joint purchases from EU and non-EU suppliers, while also financing the expansion of production capacity and fostering long-term innovation.

How should the EU design defence bonds?

Defence support from the European level can come in the form of grants or loans to member-states or defence firms directly. If it is grants, then the European Commission or a new institution needs a revenue stream to repay bondholders. Conversely, if support is in the form of repayable loans, there is only a need for credit guarantees. A combination can also be envisioned: for example, the EU could provide grants for building defence infrastructure and loans to member-states which can then use those to reduce funding costs for defence firms.

Defence support from the European level can come in the form of grants or loans to member-states.

There are essentially three options for bond design: 1) injecting additional funding into existing EU instruments, many of which are part of the EU budget; 2) setting up a structure like the RRF; 3) establishing a new off-budget vehicle. There are trade-offs between the three options.

Option 1: Using existing EU instruments

Borrowed funds could be channelled into existing EU instruments. Funding could target defence R&D (the EDF), measures to ramp up production and foster joint procurement (ASAP, EDIRPA, EDIP), measures to support Ukraine (the EPF) and measures to strengthen critical infrastructure. These tools already exist or are at an advanced stage of planning, and therefore setting up new structures would be unnecessary.

In a seminal paper, legal scholars Sebastian Grund and Armin Steinbach argued that EU debt can be used to fund such programmes.9 The revenue and expenditure in the EU budget must be balanced. Member-states are legally bound to make their EU budget contributions (based on their relative GDP) cover ‘revenue’. Such revenues can encompass funds raised through debt issuance. Debt repayments are covered in two ways. First, in so-called back-to-back funding, a member-state that borrows money from the Union pays interest and eventually repays the EU for the principal of the loan, which the Commission in turn uses to repay its bond investors. Alternatively, as in the case of RRF grants that are debt-financed, all member-states ensure repayment of EU bond investors via a commitment to provide extra contributions to the EU as needed.

However, three challenges stand out. First, directly funding joint procurement through the EU budget is legally problematic, so long as the current legal interpretation of Article 41.2 TEU stands. Any funding would likely have to be directed at covering fringe costs of joint procurement, such as its administrative costs. If Article 41.2 was re-interpreted so that ‘operations’ referred only to military operations rather than procurement, a big block would be removed. A second challenge is that while neither the EDF nor EDIP depend on consensus between the member-states, the EPF does, which makes it vulnerable to vetoes from individual member-states. Third, in its current form the EPF can only be used to finance procurement for third countries, rather than for EU member-states themselves.

Option 2: A defence fund modelled on the RRF

EU funding obtained through borrowing could also be used to establish a fund modelled on the post-pandemic RRF. This defence RRF could provide both low-interest loans and grants, for which member-states would apply. Both loans and grants would target priorities agreed by the member-states during the design of the facility, such as financing purchases for Ukraine from the Ukrainian defence industrial base, increasing EU production capacity for specific defence capabilities, strengthening the resilience of critical infrastructure and erecting border defences. Disbursements from this fund would not depend on consensus between the member-states, reducing the risk of blockages.

A defence RRF would be outside the EU budget but operate within the general contours of EU law and rely on the EU to be the issuer of debt. A defence RRF would nonetheless have shortcomings. First, even though it would not be part of the EU budget, it seems unlikely that funds from such a facility would be outside the remit of EU law and could therefore not be used to directly finance the purchase of defence capabilities – reducing its impact. A second challenge is that member-states with low interest rates on their own debt would not draw on the RRF’s loan component, potentially undermining political consensus for it. Third, a defence RRF would include all 27 EU member-states, making it vulnerable to difficult countries that might seek to block progress.

Option 3: Using an off-budget instrument

Another option is establishing a new off-budget instrument. This could, in theory, be modelled on the ESM bailout fund, or the ESM itself, though that would require a major overhaul of the ESM Treaty, including an alteration of its financial stability mandate. Such an instrument (given that it is made up of eurozone countries) would automatically exclude the enfant terrible Hungary, but non-eurozone members could make ad-hoc contributions. Using the ESM itself, which has €410 billion in remaining lending capacity, would make it possible to finance defence expenditure to a greater degree than using the EU budget, which is already fully committed. But the ESM would be unable to dole out grants for defence spending – just loans, which would only be beneficial for countries that have higher borrowing costs than the ESM. Reorienting (part of) the ESM’s lending capacity towards defence would also raise concerns about removing a firewall against financial instability in the eurozone – the ESM’s current function. The governance would also be cumbersome. Any ESM disbursement decision would be subject to approval by the German Bundestag, Finnish Parliament and possible other national parliaments.

Alternatively, the ESM could be left alone and a wholly new organisation could be established. Such a structure would have two big advantages. First, its membership could consist of a coalition of willing eurozone members, non-eurozone members and potentially also non-EU members – such as Norway and the UK. Second, EU member-states that were not interested in defence borrowing would not be forced to participate and could not block progress. But such an instrument would require a new institution – and personnel – to manage it. There is also a financial downside to setting up a whole new instrument: it would need a new injection of capital from the participating countries. Unless it was established as a proper international organisation like the ESM, a defence-related special purpose vehicle (SPV) would also essentially issue bonds directly on behalf of participating member-states. Member-states’ guarantees to the SPV would therefore be counted by statistical authorities as directly adding to their debt levels. That would make the option unappealing to member-states that are already heavily indebted.

The design of defence bonds will determine what they can be used for. If funds are channelled through the EU budget, then funding ‘pure’ defence will be very challenging unless the legal interpretation of Article 41.2 changes. Conversely, using the EPF or a similar off-budget instrument would allow more flexibility in terms of what spending can cover, but also make political blockages more likely. A challenge shared by all three options is how to ensure repayment to investors who would buy EU defence bonds.

How can the EU guarantee the repayment of defence bonds?

Before the pandemic, the EU conducted small borrowing and lending operations, where it leveraged its strong credit rating to borrow at low interest rates, subsequently lending these funds on to EU member-states or third countries like Ukraine that have higher borrowing costs. The ESM has also issued supranational debt.

The challenge for EU defence bonds is that EU resources necessary to guarantee them are fully committed.

The recovery fund truly enlarged the universe of European supranational debt – from the European Investment Bank (EIB), ESM and EU – to over €1 trillion. The interest rate on such debt has tended to be slightly higher than that of France. The interest rates that European institutions pay on the various types of European bonds are similar, but there are differences: the EIB’s bonds, which have been on the market the longest, have the lowest interest rate; EU bonds have the highest; and ESM bonds stand in the middle.10

The EU’s pandemic RRF bonds will be repaid from the EU budget’s revenues – known as ‘own resources’ – over a period of around 30 years, starting at the end of the 2021-2027 EU budget cycle. To fund its budget, the EU has maximum own resources that it can call on. However, it sets much lower limits on what it can spend on outlays for agricultural subsidies, transfers to poorer regions, the EU’s Horizon research support and other programmes. The difference between the revenue and spending ceiling is the so-called ‘headroom’ against which the EU can borrow on the market. Member-states are obliged to provide funds to the EU not only to pay for ongoing EU spending programmes, but also to underwrite any borrowing obligations under the headroom. This is akin to parents not only covering their student child’s expenses but also raising their allowance to ensure they can cover any credit card debt.

To secure the large EU bond issuance for the recovery fund, member-states agreed to raise the own resources ceiling far above EU budget spending to cover an estimated 0.10-0.15 per cent of EU Gross National Income (GNI) in annual recovery fund repayments.11 In case a member-state refuses or is unable to pay its commitments to the EU, the Commission can also withhold EU transfers to that country (or its regions).

The big challenge for EU defence bond issuance is that the EU’s resources are already committed to guaranteeing the repayment of the EU’s pandemic recovery bonds. This is why, when member-states agreed to give EU budget support to Ukraine, they had to provide additional national guarantees to the EU to ensure repayment of bond holders. If the EU wants to issue additional bonds for defence, member-states will have to provide new national guarantees. Alternatively, they will have to amend the EU’s ‘own resource decision’ by unanimity – essentially committing more resources to the EU to guarantee the issuance of additional EU debt. The ESM operates differently: it has paid-in capital from eurozone countries, against which it can borrow, and it can only dole out loans, not grants. If the ESM were to dedicate part of its resources to defence, it would not need additional guarantees or a repayment stream, but it would have less lending capacity left to bail out eurozone countries in financial distress.

The EU’s support packages for Ukraine also incorporate relevant fiscal features that would be useful for defence bonds. Traditionally, such operations required a strict one-to-one match between the cash flows from EU borrowed funds and the loans the EU would give: for instance, if Ukraine received a ten-year loan, the Commission would issue a ten-year bond concurrently. With the latest macro-financial assistance plus (MFA) programme for Ukraine, the Commission pursued a “diversified funding strategy” as with the recovery fund. This allows for more flexible debt management, as the EU can issue bonds or bills at the most favourable times rather than adhering to a fixed schedule.

Conclusion

Europeans are strengthening their defences, but large capability gaps remain, and the public finances of some member-states are stretched. EU bonds offer a potential solution to bolstering Europe’s defence capabilities by leveraging the joint creditworthiness of the EU. The debt-to-GDP level of EU and even eurozone member-states varies greatly but, on average, is below that of the US. Defence bonds could therefore lift aggregate defence spending, enhance efficiencies by pooling more investment – thereby reducing duplication across member-states – and reduce free-riding by those benefiting from the security efforts of others.

Bonds could be used in various ways: to fund EU programmes, as part of a separate initiative modelled after the EU’s pandemic recovery fund, or through an entirely new instrument or institution. However, with EU finances already stretched, member-states will either need to provide financial guarantees to underwrite these bonds, commit more resources to the EU, or put up the capital for a new institution.

Defence bonds can greatly improve EU co-ordination, but they are not a free lunch. The political capital and the creditworthiness the EU would use for them are scarce resources. Political resistance to further debt mutualisation, varying national security priorities, and legal barriers pose significant obstacles. Yet, as Europe’s security environment becomes more precarious, the need for innovative defence funding solutions is undeniable. EU defence bonds can offer the necessary financial firepower to close capability gaps and strengthen Europe’s defence infrastructure. Success will depend on securing consensus among member-states and ensuring that these bonds are part of a broader, co-ordinated effort to enhance European security in the long term.

2: Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Opening remarks at the joint press conference with President Michel and Belgian President De Croo following the meeting of the European Council of 27 June 2024’, June 27th 2024.

3: Mario Draghi, ‘The future of European competitiveness’, September 9th 2024.

4: EIB, ‘The EIB continues its support to the EU’s Security and Defence Agenda’, March 10th 2022.

5: EIB, ‘EIB Board of Directors steps up support for Europe’s security and defence industry and approves €4.5 billion in other financing’, May 8th 2024.

6: European Council, ‘Conclusions’, June 27th 2024.

7: Enrico Letta, ‘Much more than a market. Speed, security, solidarity: Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens’, April 2024.

8: Guntram Wolff, Armin Steinbach, ‘Financing European air defence through European Union debt’, Bruegel, September 17th 2024.

9: Sebastian Grund, Armin Steinbach, ‘European Union debt financing: leeway and barriers from a legal perspective’, Bruegel, September 12th 2023.

10: Kalin Anev Janse, ‘Developing European safe assets’, Intereconomics, 2023.

11: Grégory Claeys, Conor McCaffrey and Lennard Welslau, ‘What will it cost the European Union to pay its economic recovery debt?’, Bruegel, October 9th 2023.

Luigi Scazzieri is a senior research fellow and Sander Tordoir is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform.

November 2024

View press release

Download full publication