Draghi's plan to rescue the European economy: Will EU leaders do whatever it takes?

- Draghi’s report on the ailing European economy contains hard truths for EU leaders, who have long failed to confront Europe’s declining growth rate head-on.

- The report’s diagnosis is hard to argue with: Europe’s innovative capacity is declining, compared with other major advanced economies, as is its business dynamism. Intensifying state-led Chinese competition, geopolitical tensions and continued reliance on imported energy mean that policy procrastination could lead to permanent stagnation, or worse.

- Some of Draghi’s proposed fixes are new, even ground-breaking. Others have been in the EU debate for a long time. The report’s vital contribution is that it brings them together into a coherent growth agenda and that it tries to recognise the trade-offs involved in delivering it. In five areas, Draghi’s proposals will spark especially fierce debates about the direction of EU economic policy.

- First, Draghi rightly identifies Europe’s competitiveness challenge as being about improving productivity, including by closing an annual private and public investment gap of around €800 billion. He implicitly rejects boosting exports through wage repression and overly tight budgets, a strategy which served Europe poorly during the eurozone debt crisis and would backfire even more in a protectionist era.

- But Germany and many frugal member-states are still wedded to the export-led model of growth. And the EU policy framework is poorly equipped to run an economy ‘hot’ with internal demand: fiscal rules remain quite strict and the EU’s pandemic recovery fund will run out in 2026.

- Second, Draghi shifts away from a yes-or-no debate on industrial policy to a nuanced when-and-how discussion considering the characteristics of each industry, its prospects and its strategic value. He distinguishes between sectors where the EU has lost its comparative advantage entirely, those that are employment-rich, those that are critical for security, and infant industries: they all require a different mix of trade and industrial policies ranging from accepting imports to bringing in foreign technology to setting up trade protections.

- In practice, the EU will find it challenging to be hard-nosed in responding to demands by EU firms for aid and protection, to avoid wasting taxpayer money and to avoid helping incumbents over younger and more innovative firms. Draghi also advocates a tougher EU line on Chinese mercantilism and closer alignment with the US, which will prove controversial. Critics will fret that the EU taking a more hawkish line on China could be the final nail in the coffin of the frail rules-based trade system, on which the EU itself remains deeply reliant, and it could undermine developing countries.

- Third, Draghi suggests that competition authorities take more account of innovation and common continental interests like security. These are sound ideas in principle and Draghi’s approach is hardly an unconditional endorsement of ‘European champions’. However, his reform proposals still carry risks which are not fully acknowledged and are not always consistent with each other.

- Fourth, the report calls for more joint decision-making in key economic policy areas. More majority voting and common regulatory frameworks to escape the patchwork of national ones would strengthen the EU’s economic capacity to act. But member-state reluctance to cede sovereignty will make this politically difficult, leaving the EU vulnerable to ill-coordinated policies and pressure from external powers on individual member-states.

- Fifth, the EU will need money to achieve some of these objectives. Draghi suggests scaling up the EU budget and redirecting spending to strategic priorities. But fundamental reform of the EU budget has repeatedly proved impossible, while national budgets in many member-states are stretched. Draghi’s suggestion for some common debt may be unavoidable but it is controversial, even if it is only used for productivity-increasing investments in EU public goods such as breakthrough innovations, defence and cross-border energy infrastructure.

- Immediate outcries from some German politicians stumbling over Draghi’s reference to common debt do not bode well, even though Germany, as the EU’s stagnant industrial powerhouse, would be a major beneficiary from an EU growth agenda.

- Draghi’s sectoral proposals for innovation, energy and defence should be more uncontroversial. He suggests more funding for research and rolling back excessive regulation and cross-border barriers in the single market, all of which hamper the efforts of innovative European firms to scale up. Like Enrico Letta in his single market report, Draghi stresses that unlocking more high-risk investment through deeper and more liquid capital markets is critical.

- As ways of lowering energy prices, the report advocates improved collective gas procurement, stronger regulation of gas trading practices and accelerating technology-neutral energy decarbonisation. Draghi also rightly advocates for more funding, industry consolidation and enhanced EU co-ordination to counteract the EU’s fragmented defence sector.

- Implementing these plans will still be difficult: member-states have so far been reluctant to give additional powers to Brussels in these areas, for example over defence policies and procurement.

- Draghi poses the right challenge to EU policy-makers in an age of increased geopolitical competition and burgeoning investment needs. But will EU member-states rise to meet it? Or succumb to the narcissism of their differences and face a ‘slow agony’ of fading growth, economic heft and global influence?

On September 9th 2024, Mario Draghi launched his report ‘The future of EU competitiveness’, which European policy-makers had eagerly anticipated. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had tasked the former president of the European Central Bank (ECB) and former Italian prime minister with producing a plan to jolt the stalling European economy into a higher gear. Draghi’s report follows an April report to the European Council, on completing the EU single market, by another former Italian prime minister, Enrico Letta.1

Such reports often lack punch, because the outside expert is not free to speak their mind, internalises too many different perspectives, or is not clear about what their main message is. The Draghi report does not suffer from these drawbacks. It provides a sober and downbeat assessment of the European economy’s woes, a series of ambitions which are more realistic than those usually trumpeted by EU leaders and a clear-eyed set of reform proposals to achieve those ambitions. Draghi’s overriding message is that the European economy has lost dynamism and slow economic growth is accelerating Europe’s relative decline, while the surrounding political environment is becoming more hostile. Member-states will need to coalesce around a coherent plan to boost growth and rescue the European economy if they want to keep the continent prosperous enough to defend its social and political model.

The report advances three priorities: first, Europe must refocus its collective efforts on closing the innovation gap with the US and China so that it can remain a player in emerging technologies, having already lost the battle for many existing technologies. Second, the EU needs to blend decarbonisation objectives with retaining competitiveness, including by building a competitive green industry of its own rather than relying solely on Chinese imports. And third, the EU should increase its security and reduce external dependencies, by pursuing access to critical raw materials, developing its own digital services and strengthening its defence industry. Draghi’s report contains many proposals addressing these three priorities, calibrated to be implementable over the next few years.

This policy brief assesses the key themes of Draghi’s report, notably its diagnosis and proposals to boost innovation, reform industrial and trade policy, strengthen energy independence, accelerate decarbonisation and foster common defence capabilities. We also look at Draghi’s suggestions on how to finance investment – the most controversial of his proposals in EU capitals.

Member-states will need to coalesce around a coherent plan to boost growth and rescue the European economy.

The Draghi diagnosis

Mario Draghi’s sombre diagnosis is bold but hard to argue with. The European economy grew at around 2 to 3 per cent a year throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. But growth never fully recovered after the 2008 financial crisis. While Europe continues to rank highly on broader measures of wellbeing, its meagre growth has fallen well behind that of the US. Around 70 per cent of the EU’s gap in GDP per capita (in purchasing power terms) with the US is explained by lower productivity growth. With the EU workforce shrinking, Europe’s current rate of productivity would only be sufficient to maintain the economy at its present size until 2050. And Europe faces considerable structural headwinds. Chinese exports of goods such as cars and machinery are ramping up, threatening key pillars of the European economy.2 Europe also lags in technology creation and diffusion, just as a potential AI revolution might unlock new productivity gains. Businesses complain that, in some cases, recent EU regulation is more of a hindrance than a help in promoting cross-border economic activity to boost Europe’s single market.

The report’s fundamental assessment – that Europe is stuck with a “static industrial structure”, with little business dynamism and few high-growth sectors – should be telling for many EU leaders. Many of them think of Europe’s competitiveness challenge only as a question of how to help existing iconic industries maintain global market share. This has contributed to proposals to protect such sectors from radical innovation, such as by extending the deadline to end sales of traditional combustion engine cars. Draghi skates over the fact that exposure to radical disruption has helped generate the high levels of business dynamism in the US – even if it has resulted in deindustrialisation. Instead, he tries to persuade EU leaders that better use of technology might help “our existing industries … stay at the front”. However, he recognises Europe must now focus on managing the impact of disruption – for example by helping workers retrain and maintaining the European welfare state – rather than protecting firms from it.

In doing so, Draghi acknowledges another difficult truth: that Europe’s digital ambitions are unrealistic. In cloud computing, for example, the EU should merely maintain a ‘foothold’ so it is not dependent on foreign suppliers when sovereignty is critical, rather than try to compete head-to-head with the US cloud giants of Amazon, Microsoft and Google. The report also delicately acknowledges that the EU can only hope to carve out a lead in “selected segments” of the AI sector and that its focus should mostly be on increasing take-up of the technology.

Draghi’s report represents a much-needed reality check for the EU’s ambitions. European leaders must address the lack of support for disruptive innovation in Europe and the difficulty entrepreneurs face in commercialising their ideas and scaling up. The report provides useful policy prescriptions, even paradigm shifts in some cases, through several key policies outlined below. Draghi also asks the EU to get serious about closing the staggering €750-800 billion investment gap to meet its decarbonisation, digitalisation, defence and growth ambitions.

The Draghi report’s diagnosis is just as relevant to the German economy as to southern Europe, if not more so. The German economy has been stagnating for years and its growth path is way below where it was if it had followed its 2010s trajectory, as show in Chart 1. So, Germany also needs an effective EU growth agenda: as Europe’s industrial heartland, it could well be the main beneficiary.3

It is unclear, however, whether the EU can unite to implement Draghi’s proposed fixes. Raising public funds will pose an enormous political challenge. EU fiscal rules – and those of several member-states – would need to be redesigned to allow for a massive increase in public investment. Draghi anticipates objections and points out that investments should greatly boost productivity, thus easing the pressure on public budgets. But politicians like Germany’s finance minister Christian Lindner have already ruled out key parts of Draghi’s proposal for public investment.4

1. Making the EU more innovative

Draghi puts enormous emphasis on technology as the most important way to boost productivity. He points out that the growing productivity gap between the EU and the US is largely explained by America’s strength and Europe’s relative weakness in high-growth technology sectors. In these sectors, Europe’s share of world trade is mostly declining and as Chart 2 shows, its share of global R&D spending trails far behind the US and China, which suggests that the EU is likely to fall further behind.

Draghi stresses the creation of innovation and suggests steps to help innovative companies grow. Why does innovation not translate into commercialisation in Europe? This is not only driven by a lack of venture capital funding, the EU’s capital markets union (CMU – which remains less than half-built), or the poor links between universities and businesses. The problem for Draghi is also that EU firms cannot grow given sluggish demand in Europe and the difficulties of operating across borders, limiting the size of their addressable market. So, they do not get financed even when funding is available and then they leave for the US. To help firms grow, drawing from an idea proposed in the Letta report, Draghi proposes to allow innovative EU start-ups to have access to a ‘28th regime’. This would allow firms to follow one set of corporate, insolvency and some labour and tax laws across the EU. While this is a worthy idea, it is unclear whether member-states will agree to give up their national competences even to a small extent, some of which – like labour and tax laws – are extremely sensitive.

Draghi also notes that innovative firms are stifled by the EU’s relentlessly increasing regulatory burdens, especially for small and medium enterprises and in the digital sector. This problem is already well-known,5 and von der Leyen’s political guidelines for the Commission emphasise the reduction of regulatory burdens. However, efforts at regulatory simplification in the EU go back decades and have typically focused only on cutting red tape – such as reporting requirements – rather than addressing the sheer complexity of the regulatory environment, such as the number of overlapping laws covering areas like use of artificial intelligence. This complexity makes it hard for firms to adapt and evolve and has a much greater impact on innovation, dynamism and economic growth in the long run. The next Commission seems likely to continue to pursue new digital laws, like the mooted Digital Fairness Act, a proposal to tackle issues like the use of deceptive or addictive product design. Many recent digital laws – such as the AI Act – have increased the overall level of regulatory burden in the EU instead of tackling divergences in national regulation.

The report also acknowledges that public funding could be spent more wisely on innovation – for example, by shifting more innovation funding to the EU level so that more funding goes to the best projects regardless of where in Europe they are located, streamlining funding programmes and reorienting funding priorities towards radical innovation. Draghi is right to point out that the EU gets too little value for its money because its innovation budgets, like the Horizon programme, are unfocused, bureaucratic, sometimes duplicative and fragmented across borders, often prioritising ‘fair distribution’ rather than the most promising projects. Strategic investments are also too small: as a result, the EU rarely pursues breakthrough innovations, such as artificial intelligence tools, with positive spillovers for the continent at large. Draghi presents a striking statistic to back this up: as a percentage of GDP, public research and innovation spending in the EU is similar to that of the US. But while in the US the vast majority is spent at the federal level, only 10 per cent of Europe’s total research and innovation spending is at the EU level. Draghi implies that this makes US spending far more efficient at driving breakthrough innovation.

2. Energy and decarbonisation

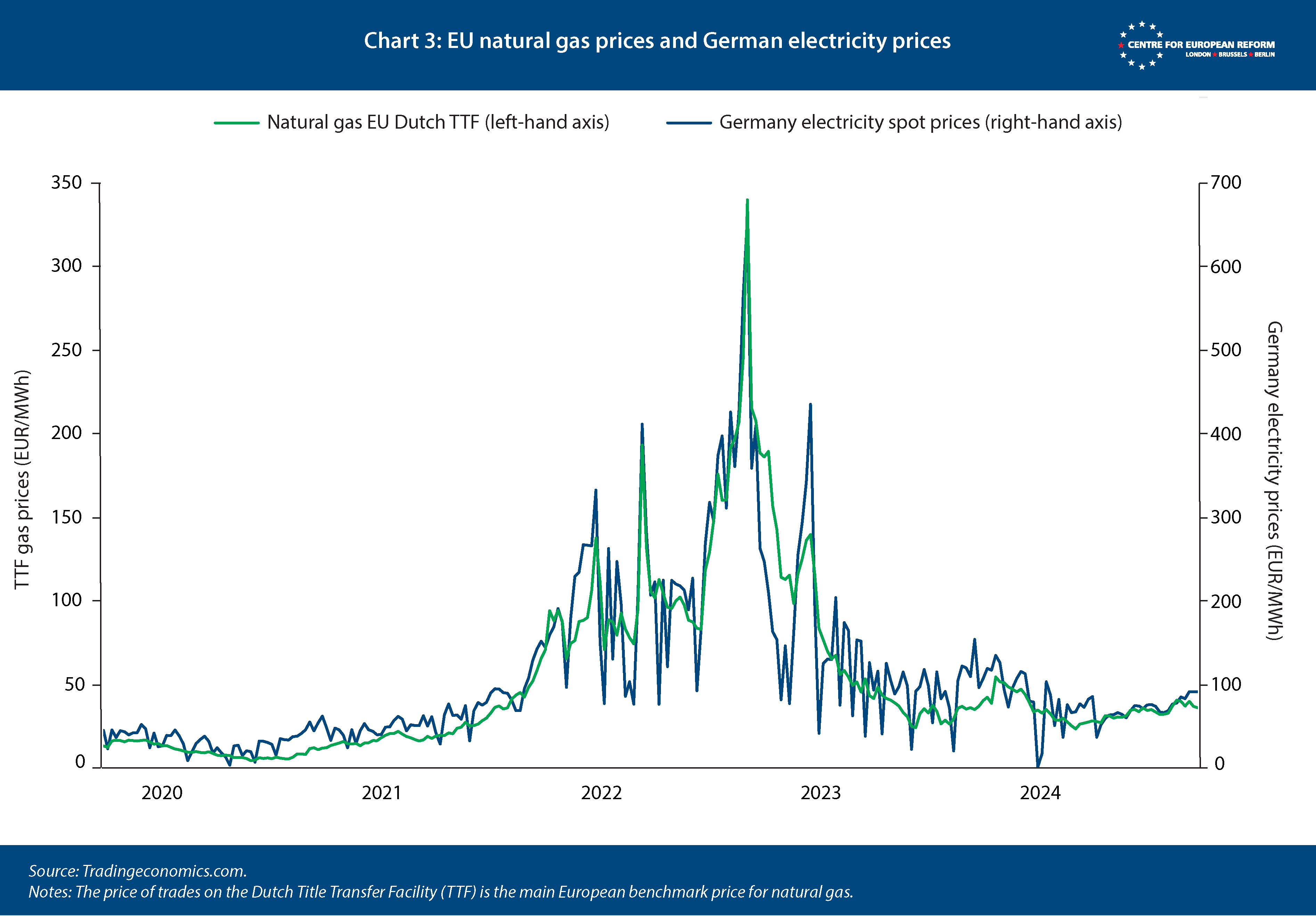

The Draghi report identifies the high cost of energy as a major brake on the competitiveness of European businesses, since their competitors in the US and China enjoy substantially lower prices. He points to weaknesses in both gas and electricity markets that, if addressed, could curb prices and their volatility. Finally, he indicates that accelerating energy decarbonisation in a technology-neutral, cost-effective way, is the key to durably lowering energy prices.

The high cost of energy is a major brake on the competitiveness of European businesses.

While the EU’s lack of natural resources cannot be solved by policy, Draghi pinpoints limited collective bargaining power on gas markets as one of the drivers of high gas prices: given gas is procured at the local as opposed to EU level, Europe is not leveraging its market scale to the fullest to negotiate better deals. This may sound like déjà vu: the Commission launched the EU Energy Platform in April 2022, precisely to facilitate demand pooling and matching with supply. Draghi suggests this concept should be expanded, becoming a platform for negotiation of long-term contracts for the entire continent – something he argues is sorely needed as part of an EU strategy to end gas import dependency.

Diversification of gas supply was part of discussions of energy security even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and it has since become a high-level political priority. But the report also shines a light on more technical and yet very consequential aspects of the energy crunch. Draghi decries the concentration of non-financial actors such as commodity traders on gas derivative markets: traders have gained record profits during the energy crunch, with speculative practices contributing to price spikes and volatility. Stronger, more coherent supervision of trading practices should put an end to these extra profits and, as such, limit gas price volatility.

On the electricity front, Draghi points to the connection between gas and electricity prices. This, again, will sound familiar to EU energy observers, given it was a key driver of the recently approved EU electricity market reform. Because gas power plants are often called upon to generate electricity at peak time, gas prices largely drive electricity prices, even though the share of gas in the power mix is shrinking (see Chart 3). Draghi’s suggested solutions are about supercharging policies that have emerged after the energy crunch. Expanding the use of long-term contracts for electricity (discussed in detail in past CER analysis)6 is a core element of the recent power market reform – Draghi suggests facilitating their uptake through government guarantees that would make them more accessible also to SMEs.

Draghi reckons that, while natural gas is still part of the EU energy mix today, it is a shrinking proportion. A key tenet of his energy proposals is that accelerating decarbonisation of the electricity sector is necessary for a durable reduction in energy prices and for EU industry to regain competitiveness. His vision of cost-efficient energy decarbonisation and of the electrification of the European economy builds on all clean technologies, from renewables to nuclear, from hydrogen to carbon capture and storage. He points out that massive investments are necessary to deliver this transformation and that they should be co-ordinated at EU level when they touch upon European public goods, such as cross-border interconnectors between power grids.

Accelerating decarbonisation of the electricity sector is necessary to bring down energy prices and for EU industry to regain competitiveness.

The success of such a momentous programme of investment in infrastructure rests on at least three ingredients. Firstly, finance – one of Draghi’s most discussed recommendations (see below). Second, effective co-ordination at EU level, which would require member-states to relinquish some of their energy policy competences to the EU to achieve faster deployment of infrastructure in optimal locations and, thus, at a lower collective cost. Third, efficient permitting to kickstart infrastructure projects. If permitting is to become faster, governments need to boost the capacity of local authorities, both in terms of staff numbers and skills. This is a prime example of a skills gap that, if left unaddressed, risks holding back the infrastructure investments necessary for decarbonisation. This should sound familiar to EU leaders, as it is a bottleneck that has slowed the construction of infrastructure built with post-pandemic Next Generation EU (NGEU) funds.

The Draghi report indicates that industrial decarbonisation comes with a challenge – cleaning up energy-intensive industries (EEIs) while preserving their competitiveness – and an opportunity – maintaining EU leadership in clean technologies.

Draghi notes that the EU has been leading in the application of carbon pricing through its Emissions Trading System (ETS), balancing it with the provision of free emissions permits for EEIs to protect them from the risk of carbon leakage. Similarly, the EU adopted ambitious environmental regulations, such as that positing the phase-out of internal combustion engines for cars and the advent of electric vehicles. But he indicates that to achieve both industrial decarbonisation and EU leadership in manufacturing, businesses need additional support. This needs to come in several forms: more targeted and streamlined investment support; smart use of local content requirements to boost domestic demand for clean tech; economic foreign policy to build partnerships with allies to source raw materials; and pragmatic trade measures to protect EU producers whenever their competitors benefit from state-sponsored support.

On industrial policy, his recommendations echo von der Leyen’s plans for supporting European industry in its decarbonisation efforts through a Green Industrial Deal. Simplifying the multiplicity of EU funds always seems reasonable, whereas finding additional funds will be tricky but is fundamental, be it for encouraging traditional industry to clean up its act or to support infant green tech industry. Draghi mentions the car industry as an example of mismatch between environmental regulation – which pushed ahead with ambitious goals – and industrial policy support – a belated policy addition. However, one could ask whether existing industries have delayed clean tech investments for lack of funds, or rather for lack of vision. The slow shift of the European car sector to EV manufacturing, which has left China plenty of time to become the market leader, is a case in point.

3. A less naive industrial and trade policy model

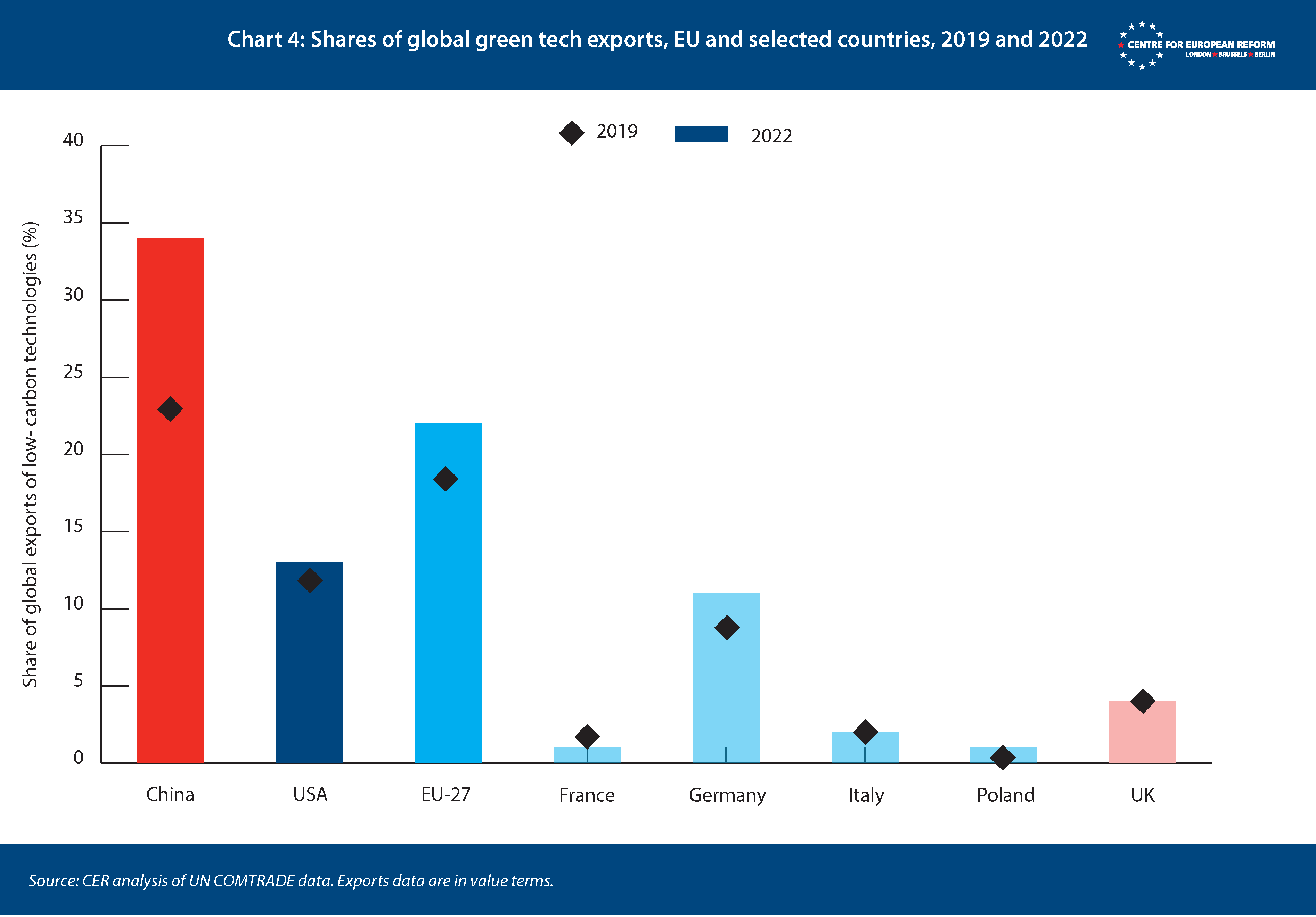

The European economy is much more dependent on trade than the American one and Europe relies heavily on fraying international law to keep markets open. Draghi did not mince his words in launching his report, stressing that Europe is vulnerable when its key trading partners no longer play by the rules. Europe’s traditional openness to imports needs to be matched by a willingness to confront and offset threats, especially the one posed to the EU’s productive clean industries by China’s system of buy-Chinese policies, protectionism and pervasive state subsidies. Although the EU’s share of global green tech exports is well ahead of the US’s, it is well behind China’s and growing much more slowly, as shown in Chart 4. The EU should act carefully, but Draghi is right to argue that inaction in the face of China’s state-sponsored competition would be detrimental to the EU’s security and to its economic growth, as the EU’s promising cleantech manufacturing sector shrinks and public support for the green transition declines.

The Draghi report provides a sharp but accurate critique of the current state of EU industrial policy, which is unfit to meet the challenge from China and geopolitical competition more broadly. Modern industrial policy demands co-ordination between fiscal policy to incentivise production, trade policy to manage external pressures and foreign policy to secure supply chains. Draghi is right to point out that in the EU these policies often work at cross purposes because they are dispersed between the national and EU levels and across and within European institutions.

Draghi is critical of the Franco-German initiative to loosen state aid curbs on national industrial policy. This is a dead end for Europe: letting EU member-states continue to lavish state aid on their own firms could threaten the level playing field of the internal market, which the EU needs to ensure that its industries remain globally competitive. Draghi sensibly proposes to roll back these exemptions from state aid rules and argues that such aid should in future only be used for strategic ‘important projects of common European interest’ (IPCEIs). IPCEIs themselves need reform, however: state aid for cross-border European projects has been under-used except for battery production, largely because the process for obtaining funding is slow and bureaucratic. Like for corporate frameworks more broadly, the report advocates for a special IPCEI framework outside the 27 national legal frameworks as well as new fast-track tools to approve and implement critical projects, for example in semiconductors and energy interconnectors.

Industrial policy is undeveloped at the European level, where the focus has traditionally been on constraining state aid.

Trade policy: Openings for deepening transatlantic co-operation

Global trade policy is increasingly centered around the US-China rivalry, increased mercantilism and security concerns. Draghi understands that European interests are often best served by close co-operation with the US, because of Europe’s dependencies on the US for technology, exports and security. But to defend European interests, Draghi argues that the EU must also get its own house in order. Trade policy must be tightly co-ordinated with and even subordinated to, industrial policy. Trade policy is an EU competence par excellence and has been one of the few areas where the EU could negotiate with the US as an equal. Industrial policy, however, is undeveloped at the European level, where the focus has traditionally been on constraining state aid. A cohesive approach to avoid fracturing the single market would require at a minimum Draghi’s proposed reforms on state aid and IPCEIs.

Trade is also an area where EU policy has been consistent in supporting the multilateral system. Draghi pays lip-service to reforming the World Trade Organisation (WTO), but it is unclear how serious he is about the WTO: he seems to suggest the EU should defend its interests even when WTO rules prove too constraining. It is true that WTO rules are not well-adapted to addressing Chinese economic policy, but if the EU follows the US in moving beyond WTO rules it needs to take care to avoid contributing to increased trade fragmentation. When there is a dilemma between WTO rules and EU-US co-operation, Draghi tends to argue that the EU should prioritise co-operation with the US. This is a difficult and necessary debate that the EU will have to confront.

The best example is Draghi’s suggestion to agree with international partners on common commitments to decarbonise, in exchange for exempting their products from the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – even if they do not have a carbon pricing mechanism equivalent to Europe’s. The EU and the US have been negotiating a US exemption from CBAM, but such a deal has remained out of reach ‘because it is difficult to reconcile with WTO non-discrimination principles. Draghi suggests that such a deal would boost EU-US trade relations and it would represent a move towards a ‘trade NATO’. Such an alliance could also tackle other shared challenges like access to critical raw materials and production of semiconductors. This risks fracturing the global trade order. Exempting the US from CBAM is also controversial. It may undermine the rationale of the newly-implemented law, which is to provide a clear carbon price signal to encourage industrial decarbonisation beyond the EU’s borders in the same way the bloc does domestically. The EU and the US have the same objective. But the US has preferred subsidising green production to putting a price on carbon, which risks putting European manufacturers at a disadvantage.

What sectors should industrial strategy cover?

The report’s most important contribution is to provide an intellectual framework for a more coherent EU industrial and trade policy, designed sector-by-sector. Draghi distinguishes between four cases. First, in areas like solar panels, where the EU has entirely lost its comparative advantage, the EU should accept Chinese imports. He is right: regaining competitiveness in this sector would require excessive and wasteful taxpayer subsidies and make decarbonisation more expensive for European consumers. Second, where the EU needs to retain domestic production and jobs, it should employ trade and industrial policies to protect EU industry from unfair competition. In employment-rich areas such as the car industry – which support millions of jobs in the EU, but whose technology is not necessarily strategic from a security perspective – the EU could welcome Chinese investment. Third, in security-relevant sectors, the EU needs to own both the know-how and the means of production in case of an escalation of geopolitical tensions. The continent can sustain its home-grown market for such sectors through the application of local content requirements on national security grounds. And fourth, in infant industries where the EU has an innovative advantage and sees high future growth potential, it should deploy (temporary) trade protections to prevent China’s overcapacity and protectionism from hampering EU innovation. Many of these proposals would push the boundaries of WTO law. Since the EU, unlike the US, is subject to dispute settlement mechanisms it will have to find ways to square the circle of WTO compliance with an active industrial policy. The car sector could be an example of this, where the EU’s proposed tariffs on Chinese electric cars are designed to comply with WTO procedures.

The EU will have to find ways to square an active industrial policy with WTO compliance.

How should industrial strategy be designed?

Building a coherent industrial policy using Draghi’s blueprint will take time, but the EU could quickly enact several of his suggested measures. Brussels could act on its investigations into Chinese subsidies on a swathe of greentech products with sizeable but more targeted tariffs than the US. In doing so the EU would protect critical, viable employment-rich sectors and promising infant industries whilst remaining within WTO rules. EU countries could also encourage local production by making their green subsidies conditional on firms curbing carbon emissions during production and avoiding transporting goods over long distances. This will safeguard local production because it will be challenging for non-European countries to meet stringent environmental standards and non-European production will face an inherent disadvantage when it comes to the carbon cost of transporting goods to the EU.

It is hard to disagree with Draghi’s general approach that “trade measures should be pragmatic and aligned with the overarching goal of raising productivity growth”. The risk is that EU leaders will defend some protectionist measures as promoting economic growth and productivity even when they do not. The EU will have to counter China’s surging trade imbalances and unfair practices to avoid deindustrialising more than necessary, but trade protections will come at a cost for consumers.

Some of Draghi’s suggestions, like the idea of using free trade agreements to develop privileged access to raw materials, will be hard to implement. The EU’s trading partners will likely refuse restrictions on where to send their exports and the report does not propose any ideas on how to incentivise them to prioritise the EU. In von der Leyen’s first term, the EU sought to be more strategic about using its economic policy to advance foreign policy goals with mixed success. The EU will need to find a new formula to build a successful network of like-minded partners to source clean energy and raw materials while avoiding accusations of neocolonialism.

Second, money spent defensively on preventing or limiting deindustrialisation will be money not spent on supporting innovation in new potentially higher-growth sectors of the economy where (by definition) there is currently less employment. For the EU, finding the right balance will be difficult. Draghi, to his credit, is aware of the importance of being selective and targeted. But knowing that a path is slippery does not always save you from falling once you start walking on it.

4. Competition policy

While most of the report confronts EU leaders with difficult truths based on evidence and analysis, Draghi’s proposals for reforming competition policy are a weak point.

The first problem is that his upfront messages on competition policy conflict with those buried deeper in the report. His headline points, for example, imply that he agrees with Letta and von der Leyen that competition policy needs to take more account of innovation and resilience – which means loosening the rules by allowing more mergers, facilitating more intra-industry co-operation and removing rules in the telecoms industry which aim to improve competition. Yet this sometimes sits uncomfortably with his insistence that stronger competition drives more investment, innovation and productivity. Buried deep in the report are proposals that would introduce a number of different objectives into competition law analysis and grant significant new powers to the European Commission.

A second problem is that Draghi’s proposals on competition policy contain very little evidence and are likely to create unintended consequences, such as making competition decisions in Europe less predictable and more politicised. Ultimately, the case for significant change is not made.

Take telecoms: in arguing that telecoms operators in Europe lack scale and therefore cannot invest efficiently, the report does not acknowledge the benefits that fierce competition in Europe has produced, most notably that prices for connectivity are far lower than in the US. This is an advantage for European businesses – most of which are in the business of buying, not selling, connectivity – and should help make it easier for the EU to achieve its goal of increasing business take-up of technologies like big data, cloud and AI. To reach its 2030 targets for take-up of these technologies – such as to have 75 per cent of EU companies using technologies like cloud and AI –, the EU needs enterprises to speed up adoption of those technologies (see Chart 5). There is little evidence that European businesses are slow to take up these technologies because of telecoms under-investment. Even if consolidation encourages telecoms operators to increase their investments – which is not a guaranteed outcome – the report does not weigh these benefits against the costs of higher prices.

Concerned at telecoms operators’ low profitability, Draghi’s proposal recommends a variety of poorly-evidenced ideas such as slashing regulation of dominant telecoms companies (directly allowing them to raise prices), facilitating in-country mergers (which would reduce customer choice) and forcing large tech firms to contribute to telecoms operators’ revenues – an idea which has been widely debunked as economically incoherent.7 If scale is important to help telecoms companies support investment, then the better solution is to promote more EU-wide harmonisation of telecoms laws, so that telecoms providers can adopt the same systems, practices and service offerings across the continent. That could promote more cross-border mergers, which would help European telecoms companies grow without negatively impacting competition. Draghi does suggest some sensible ideas in this respect.

Beyond the telecoms sector, Draghi’s report contains a number of other suggestions for competition policy, not all of which seem fully thought through. Recommendations that the Commission provide clearer guidance, speed up decision-making and streamline its processes are unobjectionable. One reasonable-sounding suggestion is for the Commission to give more weight to the potential impact on future innovation when assessing a merger. It is currently very difficult for merging parties to persuade the Commission that a merger which reduces competition should be allowed because it increases efficiency and thus improves incentives for investment and innovation. This could, for example, be the case if it gave the merged firm bigger economies of scale. There are currently no cases where efficiencies alone have convinced the Commission to approve a merger it would otherwise have blocked.

However, Draghi’s proposal to ensure that firms actually deliver more investment is unconvincing. For example, he suggests that merging firms commit to levels of investment when getting their merger approved and that the Commission monitors these after the merger is complete. However, it is unclear what punishments would apply if the promised investments do not happen. Unless the merger can be unwound, approving it could create harm to competition, by locking in an uncompetitive market structure, which would prove to be irreparable.

Draghi implicitly accepts EU consumers should pay higher prices to help European firms compete elsewhere in the world.

A further problem is that Draghi states that the point of allowing efficiencies must be to help firms develop “the scale needed to compete at the global level”. This is perhaps a cautious endorsement of the concept of ‘European champions’, though Draghi also envisages safeguards which will disappoint many advocates of that concept (such as preventing already-dominant companies from taking advantage of the flexibility). Nevertheless, Draghi implicitly accepts that EU consumers may have to pay higher prices to help EU corporations compete elsewhere in the world. This transfer from consumers to shareholders is hard to reconcile with the fundamental principle of EU competition law, which is to protect European consumers (Draghi is also clear that his proposals to tweak competition policy should not require treaty change). Nor are transfers from consumers to shareholders consistent with his applause for Europe’s achievements in limiting social inequality.

The report also proposes introducing a “security and resiliency assessment” into merger review. The idea of such a review is sound. Draghi rightly suggests that this assessment should be undertaken by a separate body, not the EU’s competition directorate. The directorate should then take the assessment into account in its decision. However, such an assessment will inevitably involve difficult political issues – such as considering the trustworthiness of some of the EU’s trading partners – and involves questions which do not easily fall within the scope of EU competition law. Security and resilience decisions in sensitive sectors should be made by a separate body, under a separate approval regime, rather than being incorporated into competition law assessments.

Finally and most radically, Draghi reintroduces the idea of a “new competition tool” (NCT). The NCT would allow the Commission to investigate competition problems in a market and impose structural changes to address “systemic” problems, without having to prove breaches of the law. The idea was previously rejected by member-states under the first von der Leyen Commission for being too wide-ranging, but it morphed into the much more limited Digital Markets Act, which instead established rules for large tech platforms. To make the NCT more acceptable, Draghi proposes that it would be limited to addressing specific types of problems which competition law has not addressed well. However, his list – covering issues such as markets where special consumer protection laws are justified or where economic resilience is weak – would nevertheless allow wide-ranging new regulation of many sectors of the economy. The UK competition authority – which has legal powers on which the NCT is modelled – has conducted investigations into markets as wide-ranging as airports, energy, banking, healthcare, vet services and auditing services.

5. Defence

Draghi’s report correctly identifies many of Europe’s weaknesses in defence. First, while there has been an uptick in defence spending since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the overall level remains low, given the current threats Europe faces and the level of under-spending over the past three decades. Spending on defence R&D is particularly sluggish, which hinders Europe’s ability to develop next-generation military equipment and keep up with innovation. Low defence R&D spending also limits the positive spillovers to other economic sectors. Second, Draghi is also right that European defence spending is fragmented and inefficient. Despite the existence of joint planning processes in the EU and NATO, member-states carry out defence procurement in a largely unco-ordinated manner, leading to a fragmentation of demand. At the same time, Europe’s defence industrial base remains fragmented along national lines, impeding efficiencies of scale. As a result, equipment is produced slowly and at a prohibitive cost and Europeans get less bang for their buck than the US. Many European countries buy much of their defence equipment from foreign suppliers, especially from the US.

Draghi’s report prescribes a multi-pronged approach to counter this, much of it already contained in the European Defence Industrial Strategy produced by the Commission in March this year.8 Many of his prescriptions will be familiar to EU defence analysts. First, Draghi argues that member-states should aggregate demand and foster consolidation of their defence industries. The overall aim should be setting up what Draghi calls an “integrated single market for defence products”. Draghi argues that EU competition policy should allow for mergers of defence firms to go ahead. Second, Draghi emphasises that more funding is needed to help this process of industrial de-fragmentation along, including by relaxing the European Investment Bank’s current restrictions on lending to the defence sector and by clarifying the application of Environmental Social and Governance rules to defence. Resources, Draghi insists, should focus on specific projects of common interest and high impact. Third, Draghi proposes to give the EU a co-ordinating role in all of this.

In principle, the idea of common defence planning and procurement and an integrated EU defence market makes economic and strategic sense. However, the political barriers to implementing his recommendations are formidable. Some member-states will not fully agree with Draghi’s analysis. In particular, the reliability of the figures he uses on the EU’s dependency on American equipment have been questioned by some analysts.9

In reality, member-states have little desire to give control over their defence procurement policy to the EU.

The bigger challenge, however, will be implementing some of his prescribed solutions. In principle there is not much opposition to the idea of directing some EU funding towards defence, for example to help firms expand production facilities. And the EU has been trying to foster a more co-ordinated approach to defence planning for many years, through tools such as the Capability Development Plan or the Co-ordinated Annual Review of Defence. Some of Draghi’s specific ideas for how to achieve this, like improving access to finance for the defence industry, will not be particularly controversial. Indeed, some steps in that direction have already been taken, with the EIB recently relaxing its rules on investing in the production of dual-use goods and services. Draghi’s proposal of not allowing competition policy to get in the way of mergers seems less relevant, given that the main barrier to consolidation is member-states’ desire to maintain control over their defence industries and their fear that consolidation might mean losing jobs.

Some proposals will be controversial. Draghi talks of a “prioritisation mechanism at the EU level to manage crisis situations”, for example ensuring privileged defence industry access to raw materials and energy. Draghi does not fully spell out how the mechanism would work, but he does reference recent proposals by the European Commission, that in effect would allow defence production to take priority over other types of production. Member-states are sceptical about this and unwilling to share sensitive information about their supply chains with the Commission. Draghi also talks about reforming public procurement legislation to advance a “European preference principle” in procurement, including potentially by reforming public procurement legislation. This proposal too mirrors the Commission’s approach of reducing reliance on non-EU suppliers such as the US or the UK. However, many member-states do not have the same negative view of reliance on non-EU suppliers and want to keep buying military equipment from them. There will also be broad opposition to reforms to public procurement that tie member-states’ hands. Draghi’s most controversial proposal is that of creating an “EU defence authority” to perform “EU defence joint programming and procurement”. While this is not fleshed out, it is likely to be a non-starter as member-states worry about the Commission encroaching on their choices of which defence equipment to buy and who to sell it to.

The political reality is that member-states have little desire to give control over their defence procurement policy to the EU and do not yet fully trust the Commission as a defence actor. They resist joint defence planning and many want to buy non-EU products for a range of legitimate reasons. European defence industrial integration can evolve in an organic manner, as EU funding increasingly shapes governmental and business choices, gradually making co-operation and consolidation the obvious choice. But this requires large scale funding – which may be Draghi’s biggest problem.

6. The question of funding

Draghi does not so much call for more investment, as ask how to meet the EU’s existing investment commitments. His report outlines €750-800 billion in additional annual investment required between 2025 and 2030, which would be an unprecedented surge of 4.4-4.7 per cent of EU GDP. These investment gaps are not new and are broadly in line with previous European Commission and European Central Bank estimates. The bulk stems from existing EU targets for decarbonisation (€450 billion), digitalisation (€150 billion), high-impact, innovative, transformative financial ventures that break new commercial or scientific ground known as ‘breakthrough investments’ (€100-150 billion) and NATO’s 2 per cent of GDP defence spending target (€50 billion). Draghi himself acknowledges that the scale of the investment gaps is staggering. He points out that an investment programme to close the gaps would lift the EU’s investment-to-GDP ratio back up to levels not seen since the reconstruction period after the Second World War. It is also much larger than the pandemic recovery fund, which was €800 billion (in public money) disbursed over several years.

Draghi had the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Commission run helpful simulations, which show that such a massive investment surge is feasible. It will slightly increase inflation for a period, as the supply side of the EU economy – materials, machines, workers – will struggle to keep up with the demand created by the investments, but it will not be overly distortive. Importantly, based on these simulations, around 80 per cent of the investment will have to come from the private sector. But the simulations also showed that the public sector must help unlock private investment through investment subsidies. A reduction of 2.5 per cent in the cost of private funding is necessary to unlock additional private investment of 4 per cent of EU GDP. If implemented successfully, Draghi argues the effects in terms of raising productivity will reduce the total cost of funding by about a third.

Frugal nations will resist common debt issuance, even if it is limited to €100-150 billion for breakthrough innovation.

Where the report adds a novel dimension is in Draghi's argument for more common spending to facilitate breakthrough innovation in Europe: he calls for an additional €100-150 billion in research and innovation (R&I). Frugal member-states quickly balked at the suggestion for joint funding. But it is important to put his recommendation in perspective. Even if the entirety of his recommended R&I spending were funded jointly by EU-member states, it would constitute around 12-19 per cent of the total programme. Draghi contends this spending would generate extra productivity growth, something that is confirmed by the European Commission and IMF simulations. If the EU manages to lift R&I, this could raise productivity, which in turn could bring in more tax receipts to create the fiscal space to fund other lower yielding but necessary investments, for example in climate change mitigation. While that argument is analytically compelling, it has so far not moved countries which reject further EU borrowing or direct cross-country transfers.

Draghi rightly criticises the EU budget, which accounts for about 1 per cent of EU GDP, for being too small and too unfocused to support the required public and private investment. Over 60 per cent of the 2021-2027 EU budget is allocated to cohesion policy, which supports poorer and more peripheral EU regions and agricultural subsidies, rather than the EU’s strategic objectives. Draghi stresses that EU programmes aimed at promoting regional convergence should be revised to address the changing geography of trade and innovation. As laid out in previous CER research, much of the future growth in intra-EU trade will be in services, which tend to cluster in large and rich cities, while innovation and its benefits also tend to agglomerate in a few metropolitan areas.10 By integrating European services markets and investing in second-tier cities that have the potential to take advantage, the EU would raise growth and spread activity beyond successful metropolises. But the vested interests of the member-states, the EU farming lobby and the regions that currently receive a lot of funding are likely to prevent radical changes to the allocation of funds in the 2028-2034 multiannual financial framework, the first draft of which the Commission will present in mid-2025 or 2026.

Given the difficulty of reforming the budget and stretched national budgets in many member-states, some common debt will be unavoidable if Draghi’s suggested joint investments in innovation, defence and electricity grid connectors are to be realised. Draghi is right that this would give rise to more EU safe assets, which are the best way to unlock a truly integrated European capital market, which in turn could stimulate some of the needed private investment. But the use of the ‘safe asset’ term is already backfiring politically. Germany, the Netherlands and other more frugal nations will resist more common debt issuance, even if it is limited to only a portion of the €100-150 billion required for breakthrough innovation. But Draghi could hardly have sidestepped the question of funding. His approach is wisely to ‘show, don’t tell’: he focuses on the opportunities and trade-offs. He leaves open whether member-states want to close the public funding gap through co-ordination of national budget interventions, overhauling the EU budget, issuing more common debt – or a combination thereof.

7. The question of governance

Finally, on governance, Draghi presents several promising ideas but some of them have failed to take off or deliver tangible progress in the past. He wants closer coordination through a competitiveness co-ordination framework, to align productivity policies, speed up sluggish decision-making and reduce EU overregulation. His report also acknowledges that for European public goods and common investments, competences must be transferred from the national to the EU level. But existing co-ordination through a process known as the ‘European Semester’ has often failed to yield more aligned economic and fiscal policies. Member-states have a poor compliance record with the recommendations from this process. Similarly, letting coalitions of willing member-states forge ahead with common projects without waiting for laggards is intellectually appealing. Such a multi-speed model allows willing nations to push ahead with deeper integration, while others move at their own pace, avoiding deadlock and enabling flexible progress. But that option is already available in the EU treaties and it has rarely been used by member-states. Member-states will also object to more majority, or qualified-majority voting, even if they are allowed to retain a veto over certain core interests.

Ultimately, member-states will have to allow more decisions about economic security and industrial policy to be made at the EU level. That would ensure the EU identifies its interests as a bloc and defines a clear strategy; it could give businesses more certainty and consistency about the rules across member-states, boosting investment and deepening the single market; and it would reduce the ability of China (or the US) to lean on individual member-states. When it comes to deciding on whether to align with the US on China, or standing up to Russia, co-ordination has been lacking for years. European countries have, for example, had widely different stances on letting Chinese firms build 5G infrastructure in Europe, buying Russian gas or civilian nuclear technology, or responding to US demands for expanded controls on EU semiconductor exports.

Draghi’s plans will inevitably lead to wrangling between member-states over the sharing of sovereignty.

Conclusion

Overall, Mario Draghi’s plan to resuscitate the EU economy is both comprehensive and compelling. It incorporates elements of Jean Monnet’s original vision for EU defence integration, Jacques Delors’ advocacy for the EU single market and Bidenomics’ emphasis on cleantech manufacturing and economic security. But above all, it is Draghi’s own vision, blending these influences and coupling them with a focus on innovation, investment and business dynamism, to boost economic growth in the EU.

The risk with EU growth strategies is that they end up in desk drawers, or worse, serve as a procrastination excuse for politicians to conduct strategic debates but avoid implementing the necessary reforms. It is now up to von der Leyen to act on it. But the biggest effort will have to come from the member-states, who remain in charge of many economic policy areas. The report is not without flaws – its suggestions on competition policy are not particularly compelling and the implementation of a more active trade and industrial policy is always fraught with the risk of missteps. But Europe cannot afford to sit still and must mount its own response to Chinese and US industrial policy. And at the core of Draghi’s report is a welcome focus on rebooting innovation and investment.

Some politicians from Germany and other frugal countries were quick to reject the report because of the suggestions of jointly funding strategic investments and generating more European safe assets. That criticism largely misses the real value of Draghi’s intervention, which is the blueprint it provides for a coherent EU growth strategy. It contains a rich set of proposals centred on building market scale, boosting the EU’s languishing record on innovation, enhancing the energy security of a hydrocarbon-poor continent and using sectorally-tailored industrial and trade policies to respond to China. This is what member-states should react to now, instead of discussing worn-out pros and cons of common debt issuance. That debate harks back to the eurocrisis of the early 2010s and the Covid-19 recession.

But the reality of Europe’s slow growth today is very different from the risk of a fragmentation of eurozone bond markets back then. In fact, Germany, as the EU’s industrial heartland, would stand to benefit more than most from Draghi’s proposal for a stronger European industrial policy – a reality that other member-states like France or Italy would have to confront. But Paris and Rome will also need to step up their efforts to bring their budget deficits under control. Forging consensus on funding Draghi’s own programme inevitably requires both high and low debt countries to come together.

Overall, Draghi’s diagnosis and proposals are well-founded and rooted in compelling economic analysis. It will now be up to EU Leaders, especially in France and Germany, to choose between building a real growth agenda or, as Draghi put it, seeing the European economy wither away in “slow agony”.

2: Sander Tordoir, ‘Chinese exports threaten Europe even more than the US’, Politico, June 7th 2024.

3: Lucas Guttenberg, Nils Redeker and Sander Tordoir, ‘Eine Riesenchance für Deutschland’, Handelsblatt, September 17th 2024.

4: Giovanna Faggionato and Hans von der Burchard, ‘Germany’s Lindner rejects Draghi’s common borrowing proposal’, Politico, September 9th 2024.

5: Zach Meyers, ‘Helping Europe’s digital economy take off: An agenda for the next Commission’, CER policy brief, February 20th 2024.

6: Elisabetta Cornago and Zach Meyers, ‘Reform of Europe’s wholesale power markets: In need of a jolt?’, CER insight, June 13th 2023.

7: Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications, ‘BEREC preliminary assessment of the underlying assumptions of payments from large CAPs to ISPs’, October 7th 2022.

8: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘The EU’s defence ambitions are for the long-term’, CER insight, March 13th 2024.

9: Juan Mejino and Lopez Guntram Wolff, ‘What role do imports play in European defence?’, Bruegel, July 4th 2024.

10: John Springford, Sander Tordoir and Lucas Resende Carvalho, ‘Why cities must drive growth in the EU’s single market', CER policy brief, June 20th 2024.

Sander Tordoir is chief economist, Aslak Berg is a research fellow, Elisabetta Cornago is a senior research fellow, Zach Meyers is assistant director and Luigi Scazzieri is a senior research fellow at the CER.

September 2024

View press release

Download full publication