All at sea? UK-German co-operation in the Nordic-Baltic region

This policy brief is the third of the CER/KAS project, “Plotting a Course Together: UK-EU Co-operation in Times of Uncertainty”. This paper focuses on the scope for UK-German security co-operation in the Nordic-Baltic region. The first paper focused on UK-EU co-operation in relation to Ukraine. The second looked at the prospect of a second Trump presidency and its impact on UK-EU relations.

- The Nordic-Baltic region is strategically and economically important to Germany and the UK, but remains an area of competition between the West and Russia. The Baltic Sea, in particular, is far from being a peaceful ‘NATO lake’. Regardless of how the war in Ukraine ends, Russia will remain a threat to the interests of EU and NATO countries in the Nordic-Baltic region.

- Through the Northern Group of defence ministers, and especially through its leadership of the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) the UK has become closely involved in the security of the Nordic-Baltic region. It is also provides the majority of NATO forces deployed in Estonia.

- Germany is an important security player in the region both on land and at sea. It is deploying a brigade in Lithuania on a permanent basis. Berlin is also increasing its maritime role, hosting NATO’s Baltic Maritime Component Command.

- Despite NATO efforts to increase its capabilities in the region, the routes by which it would have to reinforce allies in the region in a crisis are all vulnerable to being disrupted. For the EU, the energy security of member-states on the eastern side of the Baltic Sea is a challenge.

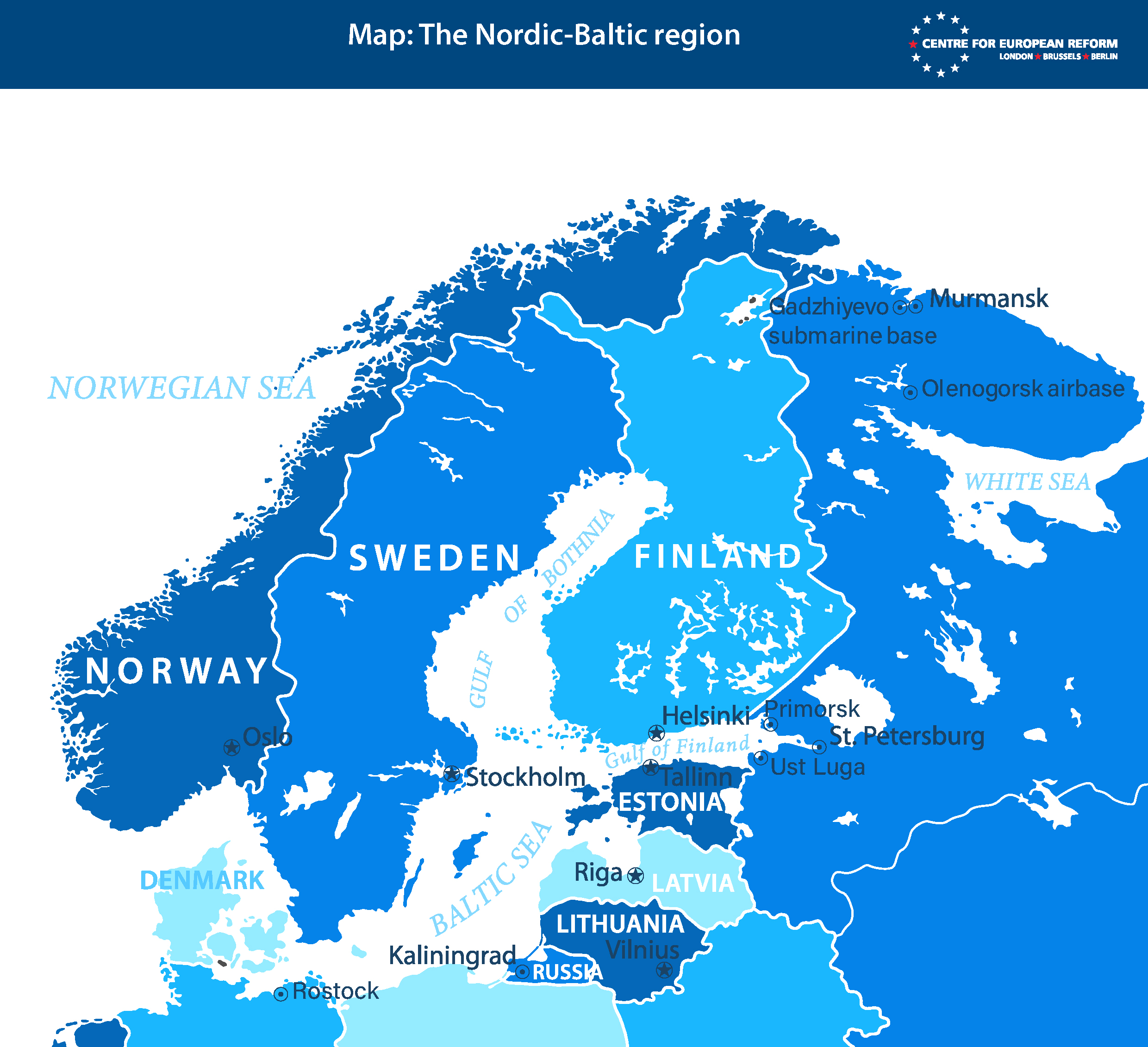

- Significant elements of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces are based in its north-west regions, near its borders with Finland and Norway. The Kaliningrad exclave on the Baltic provides a base from which Russia can threaten Western land, sea and air assets in a crisis.

- More than a third of Russian oil exports travel via the Baltic Sea. The region has been an important transit route for Russian gas exports, and may become one again if Russia can increase its exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

- Although the UK and Germany take part in a number of multilateral forums relating to the Nordic-Baltic region and have shared interests there, there is relatively little bilateral co-operation between them on regional issues. The joint declaration agreed by the new UK defence secretary and his German counterpart in July 2024 barely mentions it. On both sides, there are suspicions of the motivations of the other that need to be overcome. Some in Germany think the UK wants to use the JEF to give itself a bigger voice in European security after Brexit; some in the UK have been reluctant to involve Germany in the JEF in case it diluted the UK’s leadership role.

- A first step would be a frank discussion of the nature of the threats, the capability gaps and the scope for the UK and Germany to co-operate to fill those gaps. The UK and Germany could start a discussion, bringing in other regional players, on NATO’s complicated command arrangements for the Nordic-Baltic region. There is a case for treating the region more holistically.

- The UK should launch a process of reflection on the role of the JEF now that all its members are NATO allies. At present it sits outside NATO structures, and is supposed to be used in lower-level crises that do not engage the alliance.

- The UK and Germany should consider how they could do more in co-operation to protect critical energy and communications infrastructure in the Nordic-Baltic region, including by co-ordinated use of the Boeing P-8 maritime patrol aircraft that both operate.

- There is an opportunity for Germany and the UK to work together more closely in a region that matters to both of them.

The Nordic-Baltic region has been important to both Germany and the UK for centuries, vital at various times to either their trading or their security interests or both. It has also been a crucial area for Russia, particularly from the time of Peter the Great, who founded St Petersburg on the Gulf of Finland in 1703 as Russia’s ‘window to Europe’. The region remains an important, and contested, area for both Russia and the West, vital in particular for Europe’s energy security and Russia’s energy exports. Regardless of the outcome of its war against Ukraine, Russia will continue to pay close attention to the region, and to pose a threat to the interests of Germany, the UK and other EU and NATO members there.

After the Cold War, the Baltic region seemed destined for a period of peaceful interactions among its littoral states, with all except Russia members of either the EU, NATO or both. Berlin and London both focused on integrating the new members into the two organisations, while seeking mutually beneficial relations with Russia. All the Baltic littoral countries became members of the Council of Baltic Sea States, an organisation set up in 1992 to promote regional co-operation on issues including environmental protection, humanitarian questions, education and infrastructure. In the wider Nordic region, Finland, Norway and Sweden all sought to improve relations with Russia and to profit from commercial opportunities.

The security situation in the Nordic-Baltic region changed fundamentally after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Tension between Russia and the West grew, however, particularly after the 2014 annexation of Crimea; and the security situation in the Nordic-Baltic region changed fundamentally after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. There is renewed East-West confrontation throughout the area, where Russia shares borders with six NATO allies (Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Poland).

After Finland and Sweden joined NATO in 2023 and 2024 respectively, it is not surprising that some commentators described the Baltic Sea as a “NATO lake”; of the littoral states, only Russia is now a non-NATO (and non-EU) country.1 That ignores the fact, however, that the Baltic Sea is an international waterway, with extensive sub-sea energy and communications infrastructure that is hard to protect against covert attacks; and that Russia still has important interests in the Nordic-Baltic region.

This policy brief assesses the roles that the UK and Germany see themselves as playing in the Nordic-Baltic region and existing co-operation between them, including in the framework of NATO. The assessment is embedded in the broader context of Western and Russian interests in the Nordic-Baltic region, and current security challenges, with a particular focus on the Baltic Sea and the littoral states. Finally, the piece offers recommendations on areas for additional UK-Germany consultation and co-ordination.

The UK in the Nordic-Baltic region

In the Cold War, the UK paid close attention to the defence of Denmark, Norway and northern Germany, providing NATO’s Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces in Northern Europe (CINCNORTH), based at Allied Forces in Northern Europe (AFNORTH) headquarters near Oslo. Allied Forces Baltic Approaches (BALTAP), with German and Danish forces, was the command responsible for the eastern North Sea, the Baltic Sea and the Danish straits, as well as Denmark and the Schleswig-Holstein region of Germany. BALTAP reported to CINCNORTH. With the relaxation in East-West tension, however, NATO’s command structures changed significantly, with functional commands (for example, MARCOM, responsible for all NATO naval forces) replacing geographical commands like those for Northern Europe and the Baltic region. The UK became less engaged with the region, which was not seen as facing any significant security threats, and from 2001 its focus turned to Afghanistan and Iraq.

The UK’s re-engagement with the Nordic-Baltic region began almost accidentally in the early 2010s. The government wanted to compensate for the negative impact that reductions in UK defence capabilities based in Europe had had on the UK’s standing in NATO. The positive UK experience of working alongside Nordic and Baltic allies in NATO operations in Afghanistan meant that closer co-operation with them seemed logical. The first step was the initiative taken by then defence secretary Liam Fox to organise a ‘Northern Group’ meeting of defence ministers in Oslo in November 2010. This involved the UK, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Sweden. Fox identified a number of areas of common interest, including Afghanistan (where all 11 had troops deployed), cyber security and energy security (including the physical security of supply routes). Northern Group defence ministers continue to meet regularly, but the group has not undertaken any concrete projects; it primarily provides a forum for ministers to discuss their views ahead of NATO meetings.

The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) has proved a more useful initiative. The then UK Chief of the Defence Staff, Sir David (now Lord) Richards, laid out the concept of the JEF in a speech in 2012. The JEF was intended to be a flexible UK-led force into which allies would be able to insert units for operations anywhere in the world – based on the assumption that future wars would, like those in Iraq and Afghanistan, be fought far from Europe and not against military peer competitors.2 He expressed the hope, in passing, that Denmark and Estonia, which had fought alongside the UK in Afghanistan, might want to play a role.

Members of the JEF agreed its core area would be the High North, North Atlantic and Baltic region.

By 2014, however, the security picture in Europe had changed significantly, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its intervention in eastern Ukraine. NATO’s Wales summit in September 2014 focused on strengthening NATO’s collective defence in response to the growing Russian threat. It agreed the concept of ‘framework nations’ – whereby one nation would lead a group of others, acting as the main provider of forces and of the command structure. The group would work together to provide a capability that NATO needed. In the margins of the summit, the UK (as framework nation), Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Norway signed a letter of intent to establish the JEF as a “pool of high readiness, adaptable forces”.3 The summit declaration described the JEF as “a rapidly deployable force capable of conducting the full spectrum of operations, including high intensity operations”. Finland and Sweden joined the JEF in 2017, and Iceland in 2021.

Despite its name, the JEF is not a permanently constituted formation. Instead, it comprises various land, sea, air, space and cyber components from its member nations, which exercise together in order to increase their interoperability, and can be assembled in various configurations to respond to a crisis. Notwithstanding the Wales Summit declaration’s reference to high intensity operations, the JEF is sometimes described as a ‘sub-threshold’ capability – in other words, designed for use in situations that are not serious enough for NATO’s Article 5 mutual defence guarantee to come into play.

Though the UK initially described the JEF as “a capability that can respond anywhere in the world”, most of its members wanted to focus on concerns closer to home. In 2021, members of the JEF agreed that its core area would be “the High North, North Atlantic and Baltic Sea region” – though without excluding the possibility of deployments further afield.4 The JEF’s first (and so far only) operational deployment was of maritime and air elements in the Baltic region in December 2023, following the (seemingly intentional) cutting of a gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia and communications cables between Finland and Estonia and Finland and Sweden. The deployment was described as “a military contribution to the protection of critical undersea infrastructure” in the region.

While the JEF was developing, NATO’s 2016 Warsaw summit also announced an “enhanced forward presence” (eFP) in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland – a NATO battlegroup of about 1,000 troops in each country, each led by a framework nation. These deployments were designed to show Russia that NATO collectively stood behind the Baltic states and Poland, giving some substance to NATO’s mutual defence commitment. The UK volunteered to be the framework nation for the force in Estonia, and Germany for that in Lithuania. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Madrid NATO summit in June that year agreed that these battlegroups should be scaled up to brigade size (between 3,000 and 5,000 troops, in theory) “where and when required”. The UK has promised it will be able to deploy a full brigade in Estonia in the event of a crisis. However, in the coming years the UK’s contribution to NATO’s permanent force there is likely to decrease, at least temporarily, as it removes armoured units (which are scheduled to receive new tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles, and will need to train with them for some time) and replaces them with more lightly-armed infantry units.5

The UK has good bilateral defence relations with countries in the region. Among the most important are those with Poland, Sweden and Norway. The UK is making an important contribution to Baltic security through its involvement in Poland’s ‘Miecznik’ frigate programme. With the help of the UK defence contractor Babcock and the support of the Royal Navy, Poland is building three new ships (and may build more), which are in essence the same as the UK’s Type 31 frigates. Thales UK and MBDA UK are also involved in the project, providing technology and weapons systems. The result should be a considerable level of interoperability between the Polish and British navies once both are operating these ships.

In October 2023, Swedish prime minister Ulf Kristersson and then UK prime minister Rishi Sunak signed a ‘Strategic Partnership between the United Kingdom and Sweden’, in which among other things they agreed to deepen joint defence industrial collaboration substantially, focusing on space and underwater technology, cyber and security.6 BAE Systems owns some of the most important Swedish defence manufacturers, notably the artillery manufacturer Bofors.

In the wider Nordic region, the UK’s relationship with Norway is particularly important for Britain’s energy security: it gets more than 40 per cent of its gas from Norway – more than from the UK’s own gas fields, and more than from all other sources of gas imports combined. The gas is transported by a number of undersea pipelines. The UK has also stepped up its defence co-operation with Norway. The two had worked together for decades, with the UK’s Royal Marines exercising regularly in northern Norway. They signed a memorandum of understanding on bilateral defence co-operation in 2012, but it had no specific regional focus.7 That changed with the 2022 ‘Joint Declaration to promote bilateral strategic co-operation between the UK and Norway’, which highlighted co-ordination and dialogue on security issues in the North Atlantic, High North, Arctic and Northern Europe – also referring to the participation of both countries in the JEF and the Northern Group.8

The 2022 joint declaration was supplemented with a 2023 UK-Norway ‘Statement of Intent’ on collaboration in protecting critical energy infrastructure, sub-sea protection and anti-submarine warfare. The destruction of the Nord Stream pipelines had raised awareness of how hard it was to monitor and counter threats to sub-sea infrastructure such as pipelines, electricity cables and fibre-optic communications links.

Germany in the Nordic-Baltic region

Even during the Cold War, when much of Germany’s Baltic coast lay within the German Democratic Republic, the Baltic region was important to West Germany’s security. It was Germany that proposed the establishment of BALTAP in 1962, and although the commander was a senior Danish officer, his deputy was a German officer of the same rank. After German unification and the end of the Cold War, Germany was less focused on the military importance of the region and more on its economic significance, including for trade with Russia. Germany was a major importer of Russian oil, the majority of it shipped from the Russian ports of Primorsk and Ust Luga on the Gulf of Finland (see below). After 2011, much of the gas Germany imported from Russia came via the Nord Stream pipeline across the Baltic Sea – more than 60 per cent of it in 2021, before Russia cut the supply. As East-West tensions have grown, Germany’s military involvement in the Baltic region has also increased again.

Germany is deploying a brigade in Lithuania – its first permanent deployment outside its borders since World War Two.

Germany’s approach to security in the Nordic-Baltic region encompasses both the land and maritime elements. Of all the Baltic littoral states (other than Russia), Germany has the most powerful navy. It initiated the annual Baltic Commanders’ Conference in 2015, bringing together the naval commanders of all the Baltic littoral states except Russia. The latest meeting, held in Estonia in March 2024, focused on the security of critical undersea infrastructure. In a crisis on NATO’s eastern border, Germany would also play a crucial role in receiving reinforcements transported by sea from the US, Canada and the UK, facilitating their movement to Poland and the Baltic states and deploying its own army.

Since NATO began to increase its forces on its eastern borders, much of the focus of German activity in the region has been on land – in particular, in relation to its eFP contribution in Lithuania. Unlike the UK, which does not plan to scale up its presence in Estonia unless there is a crisis, Berlin is in the process of permanently deploying a brigade in Lithuania – Germany’s first permanent deployment outside its borders since World War Two. Almost 5,000 German troops will be stationed in Lithuania, with the brigade becoming fully operational in 2027.

Together with Denmark and Poland, Germany is also one of the framework nations for the Multinational Corps Northeast headquarters, the NATO command headquarters for the forces in Poland and the three Baltic states, which would also take command of reinforcements for the region in a crisis.

Despite the fact that Germany’s Baltic coastline stretches around 1,000 kilometres, from the Danish to the Polish border, it was slow to create a dedicated naval command structure with regional responsibility. It was only in 2019 that Germany established the German Maritime Forces Staff (DEU MARFOR) in Rostock, following a 2016 pledge to create a NATO Baltic Maritime Component Command (BMCC). DEU MARFOR will take on this Baltic command responsibility later in 2024. In peacetime, DEU MARFOR has 69 German and 21 multinational staff (including Royal Navy officers). Because Rostock was in the territory of the German Democratic Republic and the 1990 treaty on German re-unification says that foreign armed forces will not be stationed or deployed on the territory of the former GDR, non-German members of the NATO command’s staff will be based at the German navy’s Maritime Operations Centre in Glücksburg, near the Danish border.

One priority for Germany in the Baltic Sea is to improve its situational awareness – what a German officer described as “getting rid of the white spaces” on and under the surface of the Baltic, working in partnership with the private sector. Germany contributes a frigate and a minehunter to each of the two maritime components of NATO’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), one of which operates in the Baltic and the North Sea, spending about four months a year in the Baltic.

When it comes to the wider Nordic region, Berlin’s relations with Norway are also close. Like the UK, Germany has become heavily dependent on gas supplies from Norway. Even before Russia’s 2022 decision to cut gas supplies to Germany, Norway had become a major source of gas, delivered through two undersea pipelines. In 2023, it accounted for 43 per cent of Germany’s gas imports.

In the defence area, apart from regular German participation in exercises in Norway, the relationship is cemented by Norwegian purchases of German defence equipment, including submarines and Leopard 2 tanks. In 2022, following the damage to the Nord Stream pipelines, Germany and Norway jointly proposed to NATO that it should set up a co-ordination office for protecting sub-sea infrastructure – an initiative which led to the establishment of the Maritime Centre for Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure at Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM), near London. The centre, whose members are Denmark, Germany, Norway, Poland, Turkey, the UK and the US, brings together naval representatives with the private sector (which owns most of the infrastructure in question), to provide advice to the Royal Navy admiral who heads MARCOM.

EU and NATO interests in the Nordic-Baltic region

With the accession of Finland and Sweden, nine of NATO’s 32 member-states are in the Nordic-Baltic region (ten, if one includes Iceland); the six allies that share a land border with Russia are all in the region as well (Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Poland). Russia’s proximity and its hostility to NATO makes the Nordic-Baltic region acutely vulnerable to military threats and hybrid attack.

Russia’s proximity and its hostility to NATO makes the Nordic-Baltic region acutely vulnerable to military and hybrid threats.

At the Lennart Meri Conference in Tallinn in May 2024, the Inspector of the German Navy, Vice Admiral Jan Christian Kaack, suggested that despite its losses in the Black Sea, the Russian navy would “always have the initiative” in the Baltic Sea, and was increasing its capabilities, especially sub-sea.9 Though land routes will be important for reinforcing Finland and the Baltic states in a crisis or conflict, the Baltic Sea will also be a lifeline for them – but one that is easy to disrupt. After the Baltic states joined NATO in 2004, the alliance was initially reluctant to devise contingency plans for their defence, for fear of provoking Russia; it was 2010 before they were included in plans originally devised for reinforcing Poland.10 Since the annexation of Crimea, however, NATO has beefed up its efforts to deter any Russian attack on Baltic allies. And after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, NATO has also focused on having the capability in place to defend the Baltic states (rather than, as originally conceived, focusing on liberating them after occupation – an approach that was bitterly criticised by then Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas, shortly to become the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy).11

Eight of the EU-27 are also in the Nordic-Baltic region, while Norway and Iceland are members of the European Economic Area, and closely integrated into the single market. Until sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a sharp drop in purchases, the EU relied heavily on Russian oil exported from its Baltic ports. Gas flowed to Germany from Russia through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.

The reduction in flows of energy from Russia through the Baltic has not reduced the sea’s importance to EU energy security – at least, for the Baltic states and Finland. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, tankers have transported an increasing amount of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US and other suppliers to ports around the Baltic, replacing Russian gas. Estonia gets most of its energy supply by various sub-sea routes, including pipelines and power cables. The Baltic Pipe pipeline, opened in 2022, brings gas from Norway to Poland. Indeed, Norway has become the EU’s largest gas supplier, responsible for 30.3 per cent of imports in 2023 according to the European Commission. This extensive infrastructure is hard to protect (there could never be enough naval assets to cover all the potential targets) and relatively easy to attack, including from ostensibly civilian ships. It is often hard to attribute attacks with certainty, and therefore to punish those responsible. The energy supplies of most countries around the Baltic are therefore likely to remain vulnerable for the foreseeable future. For the EU, the best way to mitigate the risk to the energy security of states on the eastern side of the Baltic may be to invest more in energy sources that do not need to be imported, such as wind and hydro power, and to build so much redundancy into power grids and pipeline networks that no individual attack could cut them completely. But such steps cannot be taken overnight.

Russia in the Nordic-Baltic region

Western interests in the Nordic-Baltic region must be seen in the context of Russia’s competing interests, and the threat Russia poses to NATO and EU countries in the region. North-western Russia, the area closest to the Nordic-Baltic region, contains military facilities and commercial ports of great importance to Russia, as well as its second city, St Petersburg – doubly significant as long as Putin is in power, since it was his birthplace and original power-base.

The Kremlin will continue to attach a high priority to the security of its bases in the High North.

In the far north, on the Kola peninsula and around the White Sea, are the main bases of the Northern Fleet, such as Gadzhiyevo, from which Russian submarines carrying nuclear-armed ballistic and cruise missiles sail, as well as Olenogorsk, an airbase for long-range nuclear-capable aircraft able to strike the US. It is around 100 kilometres from the Norwegian border to the submarine bases; and around 200 kilometres to the airbase. Russia has also to take into account its 1300-kilometre border with Finland – only about 150 kilometres from the airbase in question. Before it began to prepare for the 2022 war in earnest, Russia was investing significant sums in increasing both its offensive and defensive capabilities in the Arctic and the High North, re-opening Soviet-era bases and strengthening its Northern Fleet, with its headquarters in Severomorsk, near Murmansk.

Facing demands for more forces to fight in Ukraine, for the moment Russia has prioritised the needs of the war over the defence of this area: Finnish intelligence sources believe around 80 per cent of the troops near the Finnish border have been removed and sent south, and there has been no change since Finland joined NATO in 2023.12 Given hints that Russia may revise its nuclear doctrine to broaden the circumstances in which it might use nuclear weapons, however, it is clear that the Kremlin will continue to attach a high priority to the security of these bases in the High North.13

Russia’s Baltic coastline stretches around 650 kilometres, most of it along the north and south sides of the Gulf of Finland around St Petersburg and the rest in the exclave of Kaliningrad, the main base, and sole ice-free port, of the Russian navy’s Baltic Fleet (which, like the Northern Fleet, is also nuclear-armed, though with shorter-range weapons). Kaliningrad’s surface-to-surface missiles, its air defence installations and its aircraft provide Russia with a so-called Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) capability that would make it difficult for NATO to reinforce the eastern side of the Baltic, at least initially, in a crisis.

Economically, Ust Luga, Primorsk and the Big Port of St Petersburg are the second, fourth and seventh largest cargo ports in Russia by tonnage handled, and between them Ust Luga and Primorsk handle more than a third of Russia’s oil exports – an essential source of revenue for the Russian government.14 The amount exported by the two increased from 2022 to 2023 by 9 per cent and 6.5 per cent respectively.15 Before EU sanctions on Russian oil, almost all of this oil was transported to ports in Europe; now much of it goes to India.

The Baltic Sea has also played (and may play in future) an important role in Russian gas exports to Europe. From September 2011 until it was put out of commission by explosions in September 2022 (responsibility for which remains unclear), the Nord Stream 1 pipeline from Vyborg on the Gulf of Finland in Russia to Lubmin on Germany’s Baltic coast carried 55 billion cubic metres of gas per year – more than a third of the EU’s total gas imports from Russia. The Nord Stream 2 pipeline would have carried a similar amount, but days before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Germany stopped the process of putting it into operation; one of its two lines was also destroyed by an explosion in September 2022, and the other remains inactive. Russia is also building a plant to produce LNG at Ust Luga, with a capacity of 45 billion cubic metres of gas per year. This plant was originally scheduled to come into operation in 2024, but its activation has now been put back to 2027-2028 and may be delayed further by Western sanctions on the export of LNG technology and the transport of LNG.16

Current UK-Germany co-operation in the region

On the face of it, Germany and the UK should have plenty of scope to work together against the new security challenges in the Nordic-Baltic region, both land and maritime. Each acts as the framework nation in the NATO formation defending one of the Baltic states. Germany will provide the NATO naval headquarters for the Baltic Sea. The UK leads the JEF, the maritime component of which deployed to the Baltic for the first (and so far only) time operationally in 2023 following the apparently deliberate damage to the gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia in October that year.

It might seem logical for Germany to be more closely associated with the maritime element of the JEF.

Yet when the newly appointed UK defence secretary, John Healey, signed a joint declaration on defence co-operation with his German counterpart, Boris Pistorius, on July 24th, the Baltic got only a passing mention as a subject for discussion. This was in the context of the 3+3 group of defence ministers from the three Baltic states and the three framework nations (Canada being the framework nation for NATO forces in Latvia), which meet regularly to discuss defence arrangements for the Baltic states.17

This seems to be a consistent gap in UK-German discussions of European defence and security: under the last UK government, there was no explicit mention of the Baltic in the UK-Germany joint declaration of June 2021, and the ‘joint understanding’ issued by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Chancellor Olaf Scholz after their meeting in April 2024 referred to the framework nation roles of Germany and the UK in the Baltic states, but without suggesting any specific need for them to work together in the area.

The UK and Germany work together in a variety of multilateral frameworks in the region: the Northern Group, the 3+3, a group of six North Sea states (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and the UK) that agreed in April 2024 to work together on the protection of undersea infrastructure, as well as in various NATO formats. Yet bilaterally, their regional engagement is quite insubstantial. There seem to be a variety of reasons for this.

On the German side, defence co-operation with the UK was delayed by Brexit: there was an informal agreement among EU member-states not to enter into new bilateral arrangements with the UK until EU-UK issues over the Northern Ireland protocol were resolved. By that time, Germany and the UK were both focusing on other military priorities.

Some of the UK’s rhetoric and policy decisions during that period led some in Germany (and other countries in the region) to believe that the UK saw its future security interests not in the Baltic and the North Sea, but east of Suez. Both the ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’ announced in the UK’s 2021 Integrated Review and the 2021 AUKUS agreement between Australia, the UK and the US pointed in that direction. Despite renewed British attention to European security after February 2022, there remains a sense in some allied capitals that the UK’s longstanding global naval ambitions, exemplified by the decision to build two aircraft carriers, have resulted in decisions on the mix of capabilities in the Royal Navy that are at odds with at least some of what the countries of the Nordic-Baltic region need for their defence.

An exception is the UK’s acquisition and conversion of a Norwegian offshore oilfield support vessel – now renamed the Royal Fleet Auxiliary ‘Proteus’ – to monitor and protect sub-sea infrastructure. This vessel will carry a variety of remotely-piloted sub-sea vessels and equipment that should be useful in detecting and deterring malign activity, and will be of particular relevance in the North Sea, with its high concentration of critical energy and communications infrastructure.18

It might seem logical for Germany (and Poland) to be more closely associated with the maritime element of the JEF, given the overlap of membership with the Northern Group and the Baltic Commanders’ Conference. But there are hesitations on both sides.

For Germany, the JEF itself is part of the problem: though its creation was ‘blessed’ by NATO, it is not a NATO formation, and Germany regards it as no more than a coalition of the willing. German forces can conduct operations under the aegis of collective security and defence organisations – primarily the EU, NATO and the UN – but the more informal arrangements of the JEF would not (in the view of the German authorities) satisfy Germany’s constitutional requirements. Kaack, speaking at the Lennart Meri Conference, suggested that Germany saw the JEF as a distraction from NATO activities in the region. In private discussions, there have been indications that some senior German officials also regard the JEF as a vehicle for the UK to give itself a bigger voice in European defence after Brexit, while the EU is trying to increase its own defence role.

On the British side, it is not yet clear whether the omission of an explicit mention of UK-Germany co-operation in the Nordic-Baltic region in the July 2024 joint declaration is deliberate, or merely a hangover from the Conservative government’s view. Conservative defence ministers were reluctant to try to involve Germany (or Poland) in the JEF, for example, for fear that that would dilute the UK’s leadership role in it.

Despite the creation of the new BMCC, and Germany’s role in it, there is also a tendency in London to look at Germany almost exclusively through the prism of its contribution to NATO land forces, ignoring any capabilities it might be able to bring to keeping maritime lines of communication open in the Baltic. Yet even in relation to land forces, the UK seems not to be exploiting the potential of the 3+3 format to be a forum for closer co-operation and co-ordination – indeed, all three framework nations in the Baltic states seem more often than not to act unilaterally, and not to be focused on ‘horizontal’ co-operation and co-ordination between the eFP units in the three states. One exception to this was the NATO exercise Steadfast Defender in January-May 2024, which among other things practised the overland reinforcement of the Baltic states and included the participation of the German-British Amphibious Engineer Battalion in enabling units to cross rivers en route.

Recommendations for future action

When Scholz met the new British prime minister, Keir Starmer, on August 28th 2024, they agreed to negotiate a new bilateral co-operation treaty. Defence will form an important part of this. The treaty may not go into detail on the geographical priorities for closer co-operation, but in implementing it, the two governments will need to consider where their interests are most closely aligned, and where they can both benefit from doing more together. Despite the apparent reluctance so far of both the British and German governments to get too closely involved in bilateral co-operation in the Nordic-Baltic region, they should take a fresh look at the scope for them to work together there. Perhaps the first step needed is a frank and comprehensive discussion of the nature of the threats to the whole region. Then it would be useful for London and Berlin to assess the capabilities available to Germany and the UK, the countries in the region, and the US or other NATO allies to deal with the threats; the gaps in capabilities; and the scope for the UK and Germany to contribute to filling them.

The first step needed is a comprehensive discussion of the nature of the threats to the whole region.

One issue Berlin and London could discuss, first bilaterally and then with others in the region, is how to optimise NATO’s complicated command arrangements for the Nordic-Baltic area and the surrounding seas. NATO now has regional plans, with forces allocated to carrying them out in a crisis. But the Nordic-Baltic region is divided up in ways that may not reflect the ways in which Russia could threaten it. Joint Force Command Brunssum (in the Netherlands) is responsible for the eFP formations in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, and for the defence of Northern Europe more generally. Meanwhile, Joint Force Command Norfolk (in the US) is responsible for the defence of NATO territory “from Florida to Finnmark”, as its website puts it, as well as the North Atlantic up to the North Pole. MARCOM in Northwood is “the central command of all NATO maritime forces”, and (like the two Joint Force Commands) is subordinate to Allied Command Operations at SHAPE, Belgium. With Finland and Sweden having joined NATO, they, together with Norway, will fall in the area of responsibility of Norfolk – a division of labour based on the assumption that the main challenge in a crisis in this region would be to get US reinforcements across the Atlantic to Norway, and thence via Sweden to Finland.

There is a case, made by some countries in the Nordic-Baltic region, for taking a more holistic approach to deterrence, defence and reinforcement on the eastern side of the Baltic – if not the recreation of BALTAP, then at least something like it, able to respond flexibly to disruption of reinforcement operations and to keep an overview of the area from the eastern border of Finland and the Baltic states to the eastern North Sea. The ability in a crisis to keep both land and sea routes across and around the Baltic open to NATO and as far as possible closed to Russia would be vital. Both the UK and Germany could be important players in such an approach. Others worry that too much regional integration might encourage the US to think it could safely reduce its contribution to the Nordic-Baltic region’s defence. But they should worry more about the risk that in the future the US might be unable or unwilling to send large-scale reinforcements.

The UK should also launch a process of reflection among JEF members about its function now that Finland and Sweden are NATO allies. It no longer serves its original purpose of building interoperability between NATO and non-NATO forces for expeditionary warfare; de facto, it has become a framework for a group of NATO allies with a Nordic-Baltic regional focus. At present, it serves as a vehicle for the UK to show regional leadership in crises not big enough to involve NATO; but in a major confrontation with Russia, its component parts would be transferred piecemeal to NATO command. Given the experience of its components in exercising together, it would be worth considering whether the JEF as a whole is more than the sum of its parts, and whether it could provide added value in implementing NATO’s regional plans.

A JEF that had a NATO label on it would be easier for Germany for working with; a JEF that either incorporated Germany and Poland or at least had established arrangements to work with them would provide robust land, sea and air capabilities in and for northern Europe. Such capabilities would be useful in the early stages of a confrontation with Russia, before US reinforcements began to arrive. NATO is not keen on regional forces, as opposed to multinational formations that include elements from many parts of the alliance; but in a crisis, it would be valuable to have forces in the Nordic-Baltic region that could deploy quickly, rather than waiting for reinforcements to arrive from the US or from countries in Western or Southern Europe.

Finally, the UK and Germany both have a clear interest in the security of critical infrastructure in the seas around them. Damage to it in recent years, and Russia’s specialised sub-sea capabilities, which give it the ability to attack cables and pipelines, should incentivise London and Berlin to work together bilaterally and with others to increase their ability to detect and deter hostile activity and to improve the resilience of the infrastructure. Building on the first meeting of North Sea ministers to discuss the protection of infrastructure in April 2024, the UK and Germany, as the largest naval powers among the littoral states, should consider what monitoring and deterrent capabilities would be useful in region – including unmanned as well as manned systems.19 As both countries operate Boeing P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft, there may be scope for sharing tasks and intelligence and avoiding duplication, for example.

Conclusion

The UK and Germany both have major stakes in the security of the Nordic-Baltic region, which is crucial to their security and prosperity. NATO is more capable of meeting the challenge from Russia than it would have been a few years ago, but its sea and land lines of communication in the region remain vulnerable. Above all, the energy and communications infrastructure in the region is exposed to attacks, and is hard to protect.

The UK’s new Labour government is keen to improve relations with key European partners, and Germany is taking its defence, including in the maritime domain, more seriously than it has done for many years. Clearly, there is an opportunity for the UK and Germany to enhance their co-operation in a region that matters greatly to both countries. In doing so, they can contribute more to the defence of their allies in the region, and hedge, at least partially, against the risk that the US may in future contribute less. The July joint declaration is a good start to rebuilding mutual trust between London and Berlin; it does not have to be the last word on what the two countries can do for regional security in Northern Europe.

This policy brief was written with generous support from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. The author is grateful to British, German and other officials and experts for their insights into the issues discussed. The views expressed here are those of the author alone.

2: ‘Royal United Services Institute (RUSI): Speech by General Sir David Richards, Chief of the Defence Staff’, gov.uk, December 17th 2012.

3: ‘International partners sign Joint Expeditionary Force agreement’, gov.uk, September 5th 2014.

4: ‘Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) – Policy direction’, gov.uk, July 12th 2021.

5: Tim Ripley, ‘British Battlegroup in Estonia faces Re-jig’, Defence Eye, March 8th 2024.

6: ‘Strategic Partnership between the United Kingdom and Sweden’, gov.uk website, October 13th 2023.

7:‘Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Defence of the Kingdom of Norway and the Ministry of Defence of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on the enhancement of bilateral defence co-operation’, regjeringen.no (Norwegian government website), March 6th 2012.

8: ‘Joint Declaration to promote bilateral strategic cooperation between the UK and Norway’, gov.uk, May 13th 2022.

9: ‘Can We Turn the Baltic Sea into a NATO Lake? Lennart Meri Conference 2024’, YouTube recording, May 18th 2024.

10: Ian Traynor, ‘WikiLeaks cables reveal secret Nato plans to defend Baltics from Russia’, The Guardian, December 6th 2010.

11: Richard Milne, ‘Estonia’s PM says country would be ‘wiped from map’ under existing Nato plans’, Financial Times, June 22nd 2022.

12: Mika Mäkeläinen, ‘High intelligence source to Yle: Almost all ground troops in Russia’s vicinity are now in Ukraine’, Yle Uutiset (Finnish public broadcaster), June 19th 2024.

13: ‘Senior Russian diplomat says US must take heed of discussions on nuclear doctrine’, Reuters, June 27th 2024.

14: Vladimir Afanasiev, ‘Oil exports restart at key Russian terminal after drone attack’, Upstream, January 22nd 2024.

15: Isabel Stagg, ‘Transneft pipeline oil exports down 6.5% in 2023’, World Pipelines, January 16th 2024.

16: ‘Zavod SPG v Ust’-Luge dolzhen zarabotat’ v 2027 godu’ (‘The LNG plan in Ust Luga should start operating in 2027’), Interfax (in Russian), February 5th 2024.

17: ‘Joint Declaration on Enhanced Defence Cooperation between Germany and the United Kingdom’, Ministry of Defence, July 24th 2004.

18: ‘A guide to RFA Proteus – the UK’s new seabed warfare vessel’, Navy Lookout, October 2023.

19: ‘Six North Sea countries join forces to secure critical Infrastructure: Joint Declaration on co-operation regarding protection of infrastructure in the North Sea’, regjeringen.no, April 9th 2024.

Ian Bond is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform.

September 2024

View press release

Download full publication