Five proposals for enforceable EU fiscal rules

- The EU’s fiscal rules, which guide and constrain member-states’ budget policies, are in desperate need of reform. They are too complicated, impose unrealistic demands on some countries, and lead to government overspending in economic booms and underspending in recessions. Unsurprisingly, countries barely comply with them.

- The EU should learn from its enforcement mistakes. Technocratic bodies cannot enforce the rules on their own: only the European Commission with support from member-states has the legitimacy to press a democratically elected EU government to change its budget. Hard-wired numerical rules that are imposed on a ‘one size fits all’ basis are supposed to lead to strict enforcement, but they cannot account for big economic shifts or unforeseen crises – like Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, or the Covid pandemic.

- The tension between rigid enforcement and economic reality has prompted the Commission to develop a flexible, but opaque, interpretation of the rulebook. At the same time, the political cost of sanctioning non-complying countries has time and again deterred the Commission and member-states from enforcing the rules.

- After suspending the rules in the wake of the pandemic, member-states recently asked the European Commission for a reform proposal. The Commission’s first proposal, published in November 2022, had flaws, but rightly replaced hard-coded rules that applied to all member-states with multi-year debt-reduction plans individually negotiated with each member-state, enabling each country to take ownership of its own fiscal trajectory.

- This has not pleased all member-states, though. Some capitals worry that the Commission will use its discretion to be soft on high-debt countries and want to maintain inflexible debt reduction targets. Germany has proposed that member-states with high debts cut debt-to-GDP ratios by 1 percentage point a year, which would be very difficult in periods of recession. That would once again tempt the European Commission to weaken enforcement, because some member-states would struggle to stick to the rules.

- The Commission is right to propose tailored debt reduction plans for individual countries. It needs discretion to apply the fiscal framework in a way that keeps pace with a changing growth and inflation regime and critical EU challenges like climate change or military defence. But it cannot ask member-states to trust it blindly on enforcement. The way to solve the dilemma is coupling Commission discretion with stronger enforcement mechanisms to get member-states to follow debt reduction plans. The proposals of both the Commission and the German government fell short on enforcement.

- This policy brief makes several proposals to make fiscal rule enforcement work better in the future:

- First, member-states and the Commission should agree that a portion of future EU funds will be used as incentives for good fiscal behaviour. The new fiscal framework envisioned by the Commission tries to replicate the logic of the EU pandemic recovery fund by negotiating fiscal policy bilaterally with countries, rather than seeking to constrain them solely through rules. However, under the Commission’s proposal, EU funding will not be conditional on investment and reform, unlike the recovery fund, which will expire in 2026. The EU will launch its new budget in 2027: its pay-outs should be conditional on following the rules and some funds should be set aside as rewards for high-debt countries running sustainable fiscal policies.

- Second, EU fiscal policy enforcement should closely align with national electoral cycles. The Commission initially proposed that each country should submit a four-year fiscal plan, extendable up to three years, to reduce public debt. That would be too lenient: there would be little incentive for a government with one year left to pursue reforms or public investment vigorously to avoid sanctions, or to obtain rewards from the EU institutions that only benefit the next government. Countries’ fiscal plans should cover a shorter period, such as two or three years, so that a government can reap the rewards of obeying the rules or frontloading key investments during its time in office, rather than letting its successor benefit from extra leeway or EU funds.

- Third, the new framework should prevent dangerous fiscal policy errors rather than seeking to fine-tune policy. There should be a threshold before the Commission starts investigations. An example of such a threshold would be a fiscal balance that makes a falling debt ratio probable for the most indebted EU-countries. The Commission would only spring into action if a country was on the verge of enacting policies that would lead to increasing debt levels, and turn to enforcement if it assessed that a dangerous policy error was in the making.

- Fourth, when a country’s budget is on the wrong track, the EU should redesign enforcement actions and fines so they act as a scale of escalating warning signals to bond markets, even if fines are unlikely to be imposed in practice. Making fines for less egregious fiscal mis-steps financially smaller would not reduce the political cost of imposing them – the EU has not imposed fines for non-compliance to date. But it would add more of a range of signals to bond markets about the Commission’s assessment of risks to debt sustainability. Past stand-offs between Brussels and capitals over fiscal policy have fed into higher government borrowing costs.

- Fifth, technocratic institutions like independent fiscal watchdogs can play a significant role in evaluating policy and providing technical analysis, even if they cannot be enforcers. The British Office of Budget Responsibility is a strong model. But the quality of these institutions varies widely across Europe, and whether they gain proper independence, prominence and capacity depends on the political economy of each country. To help these institutions across the continent, the EU should provide a funding base to all national fiscal institutions if conditions of independence and quality are met.

Fiscal rules aim to guide policy-makers, by committing them to long-term goals or anchors like deficit or debt levels. Based on these anchors, fiscal rules impose constraints through principles or numerical limits on expenditures, deficits, or debt. The rules are buttressed by institutions, like the European Commission or national fiscal institutions like the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, which have a double role vis-à-vis governments: analyst-advisors and rule enforcers.

Fiscal rules are needed in the EU because European, and especially eurozone, economies are deeply interwoven. A debt crisis in one country could therefore easily spread to other countries and disrupt the common market.1 And since the ECB must impose a single interest rate across the eurozone, its role becomes much harder if the state of public finances in different member-states varies too much.

The EU fiscal rules are a complex set of guidelines that nudge member-states to keep their budget deficits below 3 per cent of GDP and to bring their public debt below 60 per cent of their GDP. These thresholds are baked into the EU treaties. But the way those thresholds are implemented is governed by a set of EU rules that can be reformed through the Union’s ordinary legislative process. While the EU would need to reform its founding treaties to change the thresholds, to reform the way those thresholds work the Council of Ministers and the Parliament just need to pass a law.

The EU fiscal rules need reform.2 The rules guide government tax and spending based on indicators that tend to underestimate fiscal space in slumps. Faced with budget consolidation choices – spurred on by the rules – governments have tended to cut investment first because voters notice public spending cuts and tax rises more than cuts to investment. As a result, public investment as a share of the economy was lower in the euro area than in other advanced economies between 2011 and 2019 (except Japan), a trend that has only recently gone into reverse.3 And while the eurozone’s average public debt level is not that different from that of the United States, there is a lot of divergence, and some countries need to put debt on a downward path.

As the EU reforms fiscal rules, it should think more creatively about ways to make enforcement work better.

Member-states recently mandated the European Commission to come up with a plan to reform the rules. After the rules were suspended in the wake of the pandemic, national fiscal policies must now be brought back under an EU framework. This must be done without creating creating painful austerity unnecessarily quickly, following the debt surge during the pandemic. The Commission’s first proposal, published in November last year, did away with rules that took little account of macroeconomic conditions or political realities, and replaced them with multi-year debt-reduction plans individually negotiated with member-states, enabling them to take ownership of their own plans. Frugal member-states, worried about giving the Commission a larger role, want to go back to inflexible numerical targets for highly indebted countries to reduce their debt.

A big fight over the rules will take place after the Commission translates its proposals into a draft regulation. The Commission is now under time pressure to deliver reform: even if the member-states find agreement, any regulation will need to go through the whole EU legislative machinery – including legislative ping-pong between the Council and the Parliament. Unless a deal is made in the coming weeks, the process will spill into next year, with European elections in May 2024.

There is a way out of the conundrum: as the EU starts putting its fiscal reforms into legislation, it should think more creatively about ways to make enforcement work better, an area where the Commission’s proposal fell short. The EU could draw inspiration from recent history. This policy brief outlines five recommendations for better enforcement based on lessons from 20 years of reforms to EU fiscal rules.

Three lessons from the history of EU fiscal rule enforcement

The EU fiscal framework, officially referred to as the ‘Stability and Growth Pact’, consist of four main numerical rules:

- The deficit rule: member-states must ensure that their budget deficits do not exceed 3 per cent of their gross domestic product (GDP) in any given year.

- The debt rule: member-states must ensure that their government debt does not exceed 60 per cent of their GDP. If a member-state’s debt exceeds this threshold, it must take measures to reduce it by one-twentieth of the distance towards 60 per cent each year.

- The medium-term objective: member-states must work toward achieving a budgetary position that is close to balance or in surplus over the medium term. This means that they must strive to contain their ‘structural deficit’ to 0.5 per cent of GDP. The structural deficit is one that results from a fundamental imbalance in government receipts and expenditures, as opposed one-off or short-term factors, like a recession. If their debt is above 60 per cent of GDP, they should run a structural surplus.

- The expenditure benchmark: member-states must limit the growth in government expenditure to a medium-term benchmark of potential GDP growth plus inflation. That should automatically reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, because government expenses would grow slower than the economy as a whole.

In practice, governments have often failed to follow the four rules. A 2023 study found that, the quantitative standards were met only in half of the cases.4 In particular, the rules which guide the policy of countries that have not yet breached the 3 and 60 per cent deficit and debt targets are often violated.5

The EU cannot easily force member-states to follow the rules, unlike the United States, Germany or Switzerland, whose federal governments have more tools to impose hard debt brakes on regional governments. Because fiscal policy is still mostly in the hands of member-states, the EU institutions need a good reason to intervene. And the Commission cannot act alone – it needs the approval of the Council to sanction a member-state.

The current system of governance is the result of three sets of reforms

A 2005 reform tried to make the rules take more account of economic cycles. In 2003, Germany and France broke the rules because they felt they prevented the use of fiscal policy to overcome a period of slow economic growth.6 Eurozone finance ministers struck a deal to forgo sanctions on France and Germany and give them more time to bring down their budget deficits. A subsequent reform expanded the list of circumstances in which member-states could temporarily deviate from the general rules, such as persistent economic slowdowns, and reforms that could adversely affect national budgets in the short run.7 To provide more flexibility, the rules were also reformed on the basis of the ‘output gap’ – the unobservable gap between the economy’s current output and its maximal potential output based on all productive factors in the economy, which can only be estimated imprecisely. The idea was that linking fiscal policy space to the output gap would indicate when some of the economy’s resources were sitting idle and fiscal stimulus might help the economy to grow.

Following Greece’s government-debt crisis, which started in 2009, a second set of reforms to the EU fiscal rules in 2011 and 2013 empowered the Commission and placed greater emphasis on debt and expenditure control. The Commission’s role was strengthened because governments hoped it would be less susceptible to national political influence than the Council. The reforms changed the way the Commission could impose sanctions in the event of an EDP. Now, instead of having to approve a proposal for sanctions by qualified majority voting, the Council was deemed to agree with the Commission unless a qualified majority of its members objected. The reforms also gave the Commission the right to opine on – and even reject – draft budgetary plans before they were approved by national parliaments. The euro crisis reforms also asked national governments to establish ‘independent fiscal institutions’ at national level where they did not yet exist and established a ‘European Fiscal Board’ to provide an independent assessment of the implementation of the EU’s fiscal governance framework, in the hopes that these institutions would nudge governments to pursue sustainable fiscal policies.

A third reform in 2015 gave more leeway to the Commission in how it applied the EU fiscal framework. The euro crisis reforms had been disappointing: austerity had failed to increase economic growth, had diminished the tax base, and had eroded the ability of governments to repay their debts. After the crisis, the Commission increased its estimates of how much economic growth fiscal expansion generates, or conversely how much economic damage budget cuts do – a ratio often referred to as the ‘fiscal multiplier’.8 But the stricter rules from the euro crisis still applied, mandating a tight fiscal policy that the Commission thought was inappropriate for the economic conditions prevailing in some member-states. As a result, the Commission decided not to use its enforcement powers, recognising that forcing further budget cuts would have made the situation worse.

This shift was best captured by a 2015 Commission communication.9 It explained how the Commission would henceforth take public investments, structural reforms and cyclical conditions into account when assessing whether member-states were complying with the rules, so that EU capitals would enjoy more fiscal space. Member-states also had different views on whether more flexibility was needed, and, if so, how much. To get more fiscal space from Brussels, member-state representatives argued endlessly with the Commission and their peers over how conservative formulas for the ‘output gap’ should be.

These changes have given the Commission more flexibility in interpreting compliance with the rules and, somewhat unintentionally, made the rules themselves more complex.10 The European Fiscal Board concluded that although the flexibility provisions introduced in 2015 reduced fiscal tightening a lot, they undermined the transparency and predictability of the rules, and some member-states still failed to live up to them.11

The EU tried, and failed, to insulate rule enforcement from political pressure during the euro crisis.

This history of reform contains lessons for improving enforcement in the future.

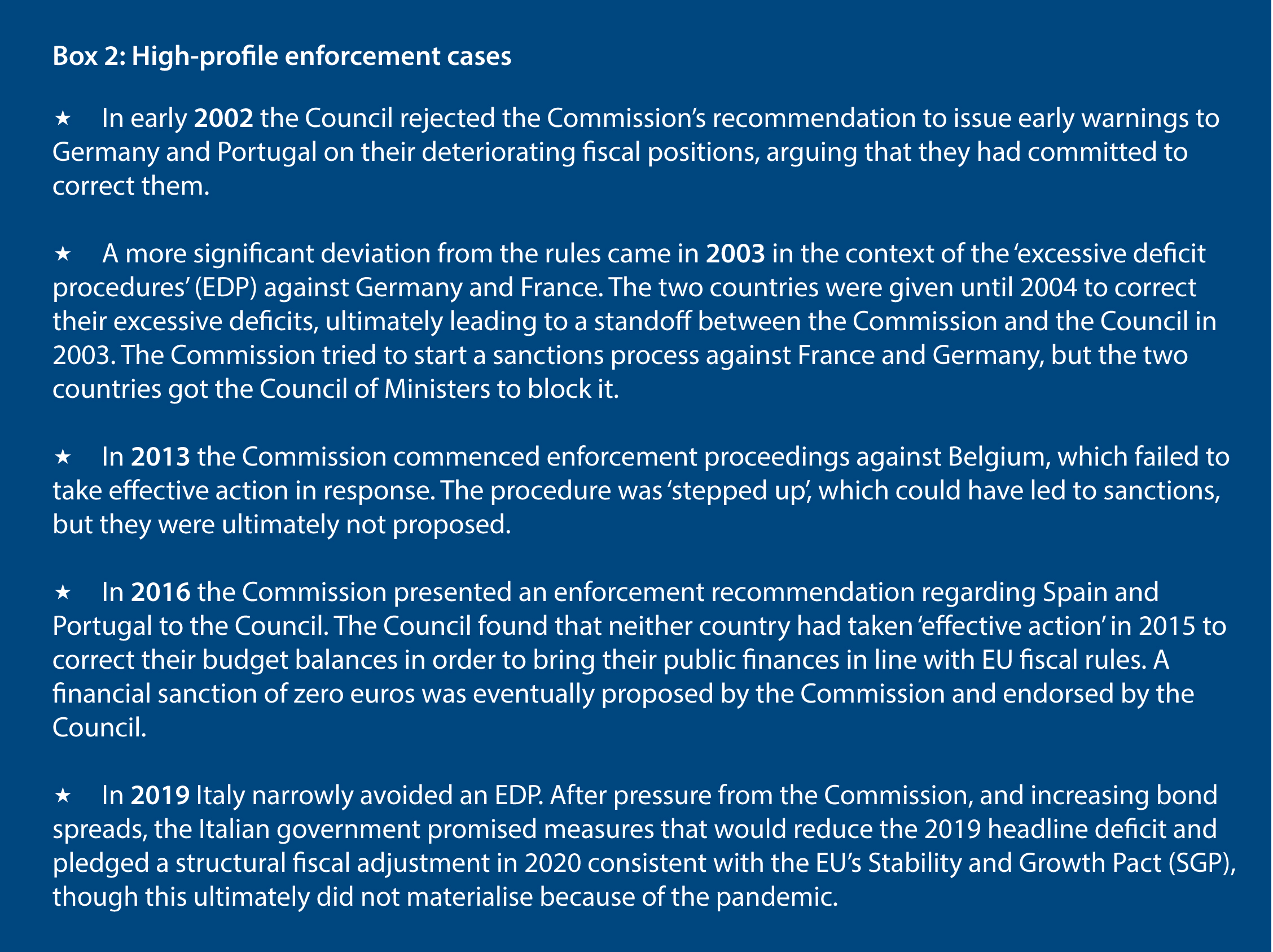

The first lesson is that there is no escape from politics: the EU tried, and failed, to insulate enforcement from political pressure during the euro crisis. In 2003, France and Germany blocked enforcement directly by rallying the Council of Ministers. After the 2011-2012 reforms, member-states lobbied the Commission for lax treatment, instead of directly blocking action. In 2016, the Commission moved to enforce against Spain and Portugal after they breached the rules and did not rein in their budgets. Portugal and Spain, supported by other member-states like Germany, could not stop the Commission from proposing a fine but pressed it to set the fine amount at zero. A gaffe from then Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker was most telling. He defended giving EU budget leeway to France in 2016 simply “because it is France”.12 Meanwhile, progress towards the establishment of national independent fiscal institutions has been sluggish and uneven across the EU and the European Fiscal Board is dependent on the Commission for its budgetary resources and access to information.

These experiences show that it is impossible to insulate EU or fiscal institutions from pressures from member-states to make their own budget choices.13 The notion that independent authorities can control fiscal policy according to automatic rules either at the European or national level may be attractive. But countries have different spending priorities, economic philosophies, party politics and electoral cycles are all very different across the bloc.14 At the same time, a common market and a currency union both require a certain degree of fiscal harmonisation. To succeed, any new EU policy must not only navigate that contradiction but embrace it.15

The second lesson is that inflexible rules cannot keep up with economic change. Strict numerical rules for debts and deficits, and automatic enforcement, are as misguided as trying to insulate the European Commission or independent fiscal watchdogs from politics. A blanket application of the 60 per cent public debt rule and of the 3 per cent deficit rule is unnecessarily strict during an economic slump: that insight drove the 2005 reform. But the real problem is that the rules themselves are only updated sporadically and have not kept pace with changes to macroeconomic conditions. In the past twenty years, the eurozone has lurched from recession in the early 2000s, to stable growth, to disinflation with low growth after the euro crisis, to the recent phase of high inflation. If the debt rule were applied to the letter of the law today, it would force countries to reduce their high post-pandemic debt-to-GDP ratios by one-twentieth every year until they reach 60 per cent, imposing draconian fiscal retrenchment upon some countries.

The pro-cyclical nature of the rules encouraged the Commission to interpret them loosely after 2015, and hold back on enforcement, to reflect economic and political reality. This interpretation made the framework more complex, and has blurred the lines between the Commission’s monitoring and enforcing roles, a competence it shares with the Council of Ministers.16 Rules can be useful to signal credibility and bring down borrowing costs.17 But they can only do this if they provide a framework that can keep up with economic developments.

The third lesson is that sanctions are impossible to implement in practice. Fines were only sporadically considered and have never been applied. For member-states and the European Commission, the political cost of enforcing sanctions on sovereign EU countries has time and again proved too high.18 Not even Germany, which must contribute most to bail-outs as the country with the deepest pockets, has been prepared follow through. Wolfgang Schäuble, the former German finance minister who was a staunch proponent of tight fiscal policy, backed out of sanctioning Spain and Portugal in 2016. He came to the aid of his political ally in Madrid, acting Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, who was also part of the European People’s Party, seeking to protect political stability in southwestern Europe.19

Just because they were never applied, however, sanctions were not without consequence. Conflicts between the Commission and national governments over fiscal policy imposed some discipline through the signal that they sent to bond markets.20 Bond yields tended to rise when EDPs were announced by the Commission. In this way, the threat of sanctions signalled whether a given conflict between the EU and a member-state was escalating. The markets seem to rely on these signals and the information they convey about the Commission’s assessment of risks to debt sustainability.

Groundhog Day? The fiscal framework emerging from EU negotiations may repeat past enforcement mistakes

In November 2022, the Commission proposed major changes to the European fiscal framework. The Treaty-based references of a deficit limit of 3 per cent and a debt limit of 60 per cent of gross domestic product would be retained. But the Commission would negotiate individual multi-year budget plans, stretching out for four years, or as much as seven when combined with agreed investments and reforms. Rather than rigid debt reduction targets that apply to all countries above the 60 per cent debt threshold, the new system would require countries to credibly commit to a debt reduction trajectory within a longer-term horizon. It would be defined by a single operational target: a net expenditure path – basically the growth rate of government spending, netted out for some factors like interest rate payments and unemployment spending (to capture the cyclical position of the economy).

The Commission’s proposal to move towards a more country-specific framework is an improvement on the old system.

To determine the stringency of a member-state’s debt reduction path, the Commission will use a ‘debt sustainability analysis’ (DSA) to assess the risk of default and whether a member-state can afford certain levels of public debt. Such analyses have long been used by international organisations like the International Monetary Fund and the Commission itself: they assess whether a government can meet current and future payment obligations based on fiscal, macro-economic and financial variables under various scenarios over an extended period, typically ten years. Countries are placed in certain categories of risk based on a combination of their current debt-to-GDP level and the odds that they will manage to stabilise or reduce these debt levels under these various scenarios. A high-risk country will have an elevated debt ratio that is increasing, rather than decreasing, under most scenarios.

As with the current rules, enforcement would happen through an EDP, which the Commission would open if countries deviated too far from the agreed debt-path or their deficit rose above three per cent of GDP. That might lead to sanctions, or freeze pay-outs from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) or the wider EU budget. The Commission proposal adds two innovations to enforcement. First, the Commission has suggested introducing ‘mini-sanctions’ for lower amounts, to make the Council more likely to agree to them. Second, reputational sanctions, including an embarrassing comply-or-explain session in the European Parliament for national ministers with runaway deficits, is supposed to further buttress the application of the rules.

Regarding enforcement, the Commission’s proposal to move towards a more country-specific framework is an improvement on the old system. The new system would remove hard-coded inflexible rules and replace them with individually negotiated multi-year plans. Such plans are intended to encourage national governments to take more ownership of their austerity programmes. Countries would also be given more fiscal latitude if they make reforms and public investment commitments that, if well-designed, could raise growth. ‘Debt sustainability analyses’ have their drawbacks, but moving away from numerical debt reduction targets creates the potential for more sensible fiscal rules that are simpler to enforce. Least controversially, a tailored net expenditure path would be the main fiscal rule for each country. That would be easy to calculate, and finance ministers could assess compliance at a glance, unlike the ‘structural fiscal balance,’ which is founded on the more obscure output gap.21

Discretion has been the key sticking point in the debate over the Commission’s proposals. Some member-states are concerned the Commission will use these greater powers, coupled with long adjustment periods, to be lenient on high-debt member-states. Others fret that top-down implementation of the rules from Brussels could be counter-productive and erode, rather than strengthen, national ownership of fiscal plans and structural reforms.

Some member-states want to curb the discretionary power of the Commission by retaining numerical debt reduction benchmarks.

Some member-states want to curb the discretionary power of the Commission by retaining numerical cross-country benchmarks. For example, Germany has been adamant that the reform should include common rules for all member-states that define structural deficits or debt ratios that are too big, with a common, transparent methodology that is applied to all member-states. In a counter-proposal in April 2023, Germany suggested that countries with high debts should cut the debt ratios by 1 percentage points a year, and those with lower debts, by 0.5 points a year. There is nothing wrong with a common, transparent methodology, but fixed rules for all countries, set overly tightly, would discourage the Commission from enforcing them, as it has happened in the past.

Fiscal policy experts have proposed another solution: to strengthen the role of independent fiscal institutions, so that they can offer a counterbalance to the Commission and national governments. But despite proposals from the IMF and the European Fiscal Board, the Commission did not propose more powers for national or European independent fiscal institutions.22 These calls have also gone unheeded in the Council so far, with some member-states preferring a return to EU-wide rules to constrain the Commission.

The Commission is right that at a bare minimum it needs some freedom in how it applies the rules – for example to agree to country-specific debt reduction paths and give countries more time to comply based on public investment or reforms that are likely to increase growth.23 But member-states are right that blind trust in the Commission is not sufficient: its proposed reforms need to be improved with a savvier enforcement process.

On that measure, the Commission proposal falls short. Smaller sanctions are not necessarily more credible: they were never applied because of their political, not their economic, cost. The Commission’s proposal to negotiate with each member-state repeats the idea behind the RRF – if you enact reforms, you get European money – but there is no permanent fiscal capacity that can provide a carrot (the RRF will end in 2026). And the idea that a national minister would come to the European Parliament to be shamed about non-compliance seems far-fetched, both as a political reality, and because Parliament does not have the legal competence to hold national ministers to account.

Without a more thoughtful process to encourage sustainable fiscal policy, it will be hard for member-states to trust the Commission and each other to enforce the EU fiscal framework.

Five proposals to strengthen SGP enforcement

The way to solve the dilemma – numerical fiscal rules or more Commission discretion – is by strengthening EU institutions and giving them instruments and incentives to nudge member-states to follow the rules. This is an area where the Commission’s original proposal fell short. Here are five ways to make fiscal rule enforcement work better:

One: Add more positive incentives

First, the EU should keep the door open for positive incentives to encourage compliance The Council should make a political commitment that pay-outs from future common EU funds will be conditional on compliance with the new rules. The RRF rewards countries financially for implementing structural reforms and making public investments: once reform and investment milestones are met, the next tranche of EU money would be disbursed.24 So far, governments’ compliance with the recovery fund has been relatively encouraging, but we are still at the start of the rollout of funds. Using positive incentives for member-states in the form of financial or other types of rewards may similarly help to enforce the fiscal rules.25 Governments are not homogenous: in fights over spending choices, there are factions in favour of following the EU fiscal rules and groups opposed to it. Giving EU money as a reward for compliance would strengthen the hand of those who want to comply with the EU framework.

If carrots are useful, where might they come from? The RRF will expire in 2026, and for now, the European Commission has avoided proposing a new common fiscal instrument for which there is no consensus amongst member-states. The EU is currently mulling the establishment a ‘sovereignty fund’ to provide industrial subsidies, but expectations are low, because there is little space left in the EU budget for new spending lines. However, the new EU budget cycle that will start in 2027 might allow fiscal policy and EU money to be linked.26 The Commission is due to make a first proposal on the budget in 2025.

EU fiscal policy enforcement should embrace the democratic nature of fiscal policy by closely aligning with electoral cycles.

Enforcement would be more credible if some future EU funding were only disbursed to governments running sustainable fiscal policies. The US system offers some lessons here. When disbursing federal aid programmes to the states, the US federal government distinguishes between block and categorical grants.27 Block grants are given for a broad purpose with few strings attached, whereas categorical grants (which are awarded through a competitive application process) can be used only for specific programmes whilst giving the federal government more power over how that money is spent and leverage over the states’ policies more broadly. The EU should consider a similar split between unconditional and conditional funding in future EU fiscal instruments, including the EU budget from 2027. Funds that serve EU public goods, like increasing climate investment or boosting military capacity, should be unconditional, because withholding such funds would hurt all other member-states. For example, it would make little sense to cut funds to a fiscally constrained country for expanding renewable energy or buying essential military equipment. But a portion of agricultural subsidies, EU structural and cohesion funds could be set aside as rewards to countries that improve their fiscal performance. New ‘own resources’ sources of revenue, for the Union’s budget post-2027 will also be discussed. The Commission can currently withhold EU funds only as the very last line of defence once the fiscal rules have been broken: in the future, they could be disbursed once countries reached the debt reduction targets and reform or investment benchmarks set out in their fiscal plans. Depending on their nature and design, member-states’ contributions to the EU budget could also be linked to responsible national fiscal policy.

Two: Align fiscal policy supervision with national electoral cycles

Second, EU fiscal policy enforcement should embrace the democratic nature of fiscal policy by closely aligning with electoral cycles. In the initial Commission proposal, the scope for a new government to present revised plans was only mentioned as an afterthought and buried in a footnote of an annex.28 Governments change all the time, so they should be able to present a new or at least revised plan with every change of stewardship. That would also encourage the new administration to take ownership. Governments are also always tempted to raise deficits to give hand-outs in the year before an election. Having a four-year fiscal plan with up to three years of extension is therefore not only conducive to abuse, but also poorly aligned with government mandates in the EU, which are typically four or five years and in practice shorter, especially since the collapse of governments has become more frequent.29 There would be little incentive for a government with one year left to pursue reforms or public investment vigorously in order to capture rewards from Brussels that only the next government would enjoy.

The timeline of the fiscal plans and any extra leeway given by the Commission should be shortened and aligned with political mandates. Member-states’ fiscal plans could cover a period of two or three years, with room for the Commission to give extra time for adjustment within a government’s mandate if it has an investment and reform programme that will credibly boost growth. For example, if a government prioritises key public investments over other spending in its first year of office, it should be given more time to reduce its deficit by the Commission in its third year in office. That would alleviate the pressure for a government to go on an unexpected election-timed spending spree, because the Commission would have already given it some extra space. If an unexpected spree does materialise, the Commission would quickly pick that up in its regular fiscal surveillance. The Commission should also not set expenditure paths before member-state governments, their national parliaments and independent fiscal institutions have a say. Thankfully, the reform is moving in this direction because there is now an agreement between the Commission and member-states “that all plans could be aligned, upon request, with the national electoral cycle and revised with the accession of new governments”.30 The timeline of the fiscal plans in the forthcoming legislation should build on that insight.

Three: Focus on gross fiscal policy errors

Third, the enforcement process should be aimed at avoiding gross fiscal policy errors, not at fine-tuning policy. The EU treaties require the Commission to monitor national fiscal policy, “with a view to identifying gross errors”.31 But the Commission currently gives fiscal policy recommendations to all member-states, including those who are fully compliant and at zero risk of debt unsustainability. That burdens the Commission’s resources and increases the danger that the Commission is seen as meddling rather than correcting problems that pose risks for the EU as a whole.

Instead of defining the expenditure path for every country, the Commission could set a common benchmark for responsible fiscal policy, for example by determining a fiscal stance that leads to a falling debt to GDP ratio for countries with the highest debt financing costs.32 The Commission would then only spring into action if it saw that a country might be on the verge of enacting policies that would instead lead to increasing debt levels. The Commission would only start enforcement proceedings when it had a reasonable suspicion that a gross error might be in the making.

Enforcement actions should be redesigned as signals to bond markets rather than as instruments to apply in practice.

Isolating the riskiest policies would help to focus the EU’s efforts on countries whose fiscal policies pose risks to others. It would also curb any temptation for the Commission to intervene unnecessarily in national fiscal policy, helping to make the rules more credible in the process. The Commission’s proposals foresee a category for countries with low debt-to-GDP levels, which are meant to undergo more limited scrutiny, but only to a limited extent. Member-states have called upon the Commission to introduce a common debt reduction benchmark in its legislative proposals for revamped rules. Making the isolation of outliers the central goal of such a benchmark would help with enforcement.

Four: Consider sanctions as signals

Fourth, sanctions should be thought of as ‘soft power’ signals to bond markets rather than as instruments that are likely to be applied in practice. Critics point to the lack of previous fines as evidence that the EU fiscal rules lack teeth. However, there is ample evidence that stand-offs between the EU institutions and member-states over fiscal policy do feed into higher borrowing costs for those member-states.33 Enforcement proceedings provide a signal to markets even if fines do not materialise.

The effectiveness of enforcement should be measured by whether the proceedings effectively communicate to markets that a country’s fiscal policy is on the wrong track. The Commission’s proposal to impose lower fines is a step in this direction because it adds another signal: if the Commission proposed a lower fine, rather than a higher one, markets would take that to mean that the Commission views one government’s policy to be less risky than another’s. The EU should therefore introduce a scale of escalation steps, possibly linked to mini-sanctions, based on the extent of deviation from the agreed path and the risks of gross policy errors. Recent ECB moves will strengthen this signalling mechanism: the new Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which will allow the ECB to buy a country’s bonds if their borrowing costs spike, can only be used if governments stick to the fiscal rules.

Five: Strengthen independent fiscal institutions

Fifth, European and national independent fiscal institutions should be strengthened. Decisions about net expenditure rules, rooted in a ‘debt sustainability analysis’ by the Commission, are based on assumptions and require complicated assessments about the long-term trajectories of macroeconomic variables. Such assessments should be debated with knowledgeable experts. The European Fiscal board and national independent fiscal institutions could provide that expertise. Such institutions cannot be enforcers: only the European Commission, with sufficient political cover from the Council of Ministers, has any potential to fulfil that role. The Commission is anchored in EU law, and member-states rely on its advice, support and administration of funds across a realm of policy fields. It also has an army of economists and experts with in-depth country knowledge at its disposal. The Council derives its legitimacy from being a court of peer member-states and, while shying away from imposing sanctions, it has often tightened recommendations against high-debt member-states.34 The independent fiscal watchdogs have less institutional legitimacy and leverage to press a democratically elected government to adjust its budget.

But fiscal watchdogs can play an important role in flagging risks of serious fiscal slippages or looming policy mistakes. The mandates and quality of these institutions vary widely across Europe. Whether they gain proper independence, prominence and capacity depends on the political economy and institutional history of each country. Transplanting a strong model - like the British Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) or the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (CPB) - to another country is extremely difficult. The CPB, for example, is not formally independent from the finance ministry. But there is a wider culture around the institution in politics and the Dutch media that gives it both prominence and an independent voice from the government. It will take a long time for the influence, quality, and public visibility of these institutions to increase in all other EU member-states, and there may be successful pressure by ministers to curb their independence. If Europe wants these institutions to succeed, they at least need adequate financing to be independent of national politics. The EU budget should provide a direct line of financing to all EU independent fiscal institutions from 2027, anchored in a political commitment that this money will not be cut or adjusted, to safeguard their independence. The UK’s OBR has a budget of about £4 million a year (although the OECD considers this too small).35 Using this as a guide, if the EU paid a similar amount to all 27 EU fiscal institutions to give them a basic level of funding, the total cost would be merely €120 million (less than 0.1 per cent of the EU budget). That is a small price for better fiscal policies across the EU. Equipping fiscal institutions with EU funding will also help to pave the way to establish a European network of fiscal institutions.

Conclusion

A desperately needed reform of the EU’s fiscal rules is finally underway. But as the EU starts legislating for the reform, it has arrived at an impasse.

The European Commission needs discretion to apply the rules in a way that keeps pace with economic developments. The same rigid rules cannot be imposed on all member-states all the time because economic and political circumstances differ between countries and Europe’s growth and inflation regime changes over time.

But the Commission cannot ask member-states to trust it blindly to be strict enough on high-debt countries. Frugal member-states, worried about a larger role for the Commission, therefore, want to go back to inflexible numerical debt reduction targets that apply to everyone. But that will only mean that member-states will lobby the Commission and the process will become opaque again.

The way to solve this dilemma is by strengthening EU institutions and giving them tools to nudge member-states to follow the rules, an area where the Commission’s autumn 2022 proposal fell short.

The Commission should only intervene when other member-states are in danger. It should have a wider range of carrots and sticks to use against member-states. Meanwhile, stronger independent fiscal institutions could help to prevent member-states from pursuing bad policies that would then lead the Commission to intervene. Strengthening enforcement is the best shot the EU has to avoid egregious fiscal policy errors, so that the whole fiscal framework is effective – not only on paper but in practice.

2: Zsolt Darvas, Philippe Martin, and Xavier Ragot, ‘European rules require a major overhaul’, Bruegel, October 2018.

3: Fabio Panetta, ‘Investing in Europe’s future: the case for a rethink’, speech at Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, November 11th 2020.

4: Martin Larch, Janis Malzubris and Stefano Santacroce, ‘Numerical Compliance with EU fiscal rules: Facts and figures from a new database’, Intereconomics, January 2023.

5: Martin Larch and Stefano Santacroce, ‘Numerical compliance with EU fiscal rules: The compliance database of the secretariat of the European Fiscal Board’, Voxeu, September 2020.

6: Mark Tran, ‘France and Germany evade deficit fines’, The Guardian, November 25th 2003.

7: Roel Beetsma and Martin Larch, ‘EU Fiscal Rules: Further reform or better implementation?’, ifo DICE Report, summer issue, 2019.

8: Lucyna Gornicka, Christophe Kamps, Gerrit Koester and Nadine Leiner-Killinger, ‘learning about fiscal multipliers during the European sovereign debt crisis: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment’, Economic Policy, May 2020.

9: European Commission, ‘Making the best use of the flexibility within the existing rules of the stability and growth pact’, January 2015.

10: Tobias Tesche, ‘Keep it complex! Prodi’s curse and the EU fiscal governance regime complex’, New Political Economy, April 2023.

11: European Fiscal Board, ’Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two-pack regulations, September 2019.

12: Francesco Guarascio, ‘EU gives budget leeway to France ‘because it is France’, Reuters, May 31st 2016.

13: Reinout van der Veer, ‘Walking the tightrope: Politicisation and the Commission’s enforcement of the SGP’, Journal of Common Market Studies, January 2022. Also see Reinout van der Veer and Markus Haverland, ‘Bread and butter or bread and circuses? Politicisation and the European Commission in the European Semester’, European Union Politics, 2018.

14: Markus Brunnermeier, Harold James and Jean-Pierre Landau, ‘The euro and the battle of ideas’, Princeton University Press, 2016.

15: Amy Verdun and Jonathan Zeitlin, ‘Introduction: The European Semester as a new architecture of EU socioeconomic governance in theory and practice’, Journal of European Public Policy, 2018.

16: Beatrice Weder di Mauro, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Hélène Rey, Nicolas Véron et al, ‘Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform’, CEPR Policy Insight, January 2018.

17: John Thornton and Chrysovalantis Chrysovalantis, ‘Fiscal rules and government borrowing costs: International evidence’, Economic Inquiry, January 2018.

18: Martin Sacher, ‘Avoiding the Inappropriate: The European Commission and Sanctions under the Stability and Growth Pact’, Politics and Governance, May 2021.

19: Florian Eder, ‘Wolfgang Schäuble bails out Spain, Portugal’, Politico Europe, July 27th 2016.

20: Konstantinos Efstathiou and Guntram Wolff, ‘What drives implementation of the European Union’s policy recommendations to its member countries?’, Bruegel, April 2022.

21: Christophe Kamps and Nadine Leiner-Killinger, ‘Taking stock of the EU fiscal rules over the past 20 years and options for reform’ Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, October 2019.

22: Olivier Blanchard, Andre Sapir and Jeromin Zettelmeyer, ‘The European Commission’s fiscal rules proposal: A bold plan with flaws that can be fixed’, Bruegel blog post, November 2022.

23: Johannes Lindner and Nils Redeker, ‘It’s the politics stupid’, Jacques Delors Policy Brief, March 2023.

24: Elisabetta Cornago and John Springford, ‘Why the EU’s recovery fund should be permanent’, CER policy brief, November 2021.

25: John Springford, ‘A new EU fiscal regime could make the ECB truly independent’, CER insight, June 2022. Also see David Bokhorst, ‘Influence of the European Semester: Case study analysis and lessons for its post-pandemic transformation’, Journal of Common Market Studies, January 2022.

26: Lucas Guttenberg, Johannes Hemker and Sander Tordoir, ‘Everything will be different: how the pandemic is changing EU economic governance’, Jacques Delors Center Policy Brief, February 2021.

27: Congressional Research Service, ‘Block Grants: Perspectives and controversies’, CRS Report, November 2022.

28: European Commission, ‘Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework’, November 2022.

29: Laura Clancy, Sarah Austin and Jordan Lippert, ‘Many countries in Europe get a new government at least every two years’, Pew Research, January 2023.

30: The Council of the European Union, ‘Economic governance framework: Council agrees its orientations for a reform’, March 2023.

31: Article 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

32: Jasper van Dijk, Florian Schuster, Philippa Sigl-Glöckner and Vinzenz Ziesemer, ‘Building on the proposal by the EU-Commission for reforming the Stability and Growth Pact’, Dezernat Zukunft/Instituut voor Publieke Economie, December 2022.

33: Federico Kalan, Adina Popescu, Julian Reynaud et al, ‘Thou Shalt Not Breach: The Impact on Sovereign Spreads of Noncomplying with the EU Fiscal Rules.’ IMF Working Paper, April 2018. Also see Antonio Alfonso, Joao Tovar Jalles and Mina Kazemi, ’The effects of macroeconomic, fiscal and monetary policy announcements on sovereign bond spreads; an event study from the EMU’, Econpol working paper, February 2019.

34: Camilla Mariotto, ‘Negotiating implementation of EU fiscal governance’, Journal of European Integration, April 2019.

35: OECD, ‘OECD independent fiscal institutions review: Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) of the United Kingdom’, OECD, September 2020.

Sander Tordoir is senior economist at the Centre for European Reform, Jasper van Dijk is research lead at the Instituut voor Publieke Economie and Vinzenz Ziesemer is director of the Instituut voor Publieke Economie

April 2023

View press release

Download full publication