Schengen reloaded

- The Schengen borderless area remains one of the EU’s most popular achievements. Though EU politicians may suggest otherwise, it does not need a complete overhaul; but it would benefit from being updated.

- Schengen works because its benefits and burdens are shared; because there is a high degree of mutual trust among its members; and because the original Schengen regime has been subsumed in the much broader EU area of freedom, security and justice, which is based on the same principles.

- In recent years, the area of freedom, security and justice has come under strain; the benefits and burdens have sometimes seemed to be unequally shared, and mutual trust has been eroding.

- Implementation is a genuine challenge for member-states: they do not all have the same administrative capacity or resources. But if member-states cannot trust each other to carry out their obligations, Schengen will not be able to function.The EU needs a peer review system to evaluate compliance with obligations, ensuring that all member-states are tested against the same benchmarks, regularly and objectively.

- Where there are shortcomings, the EU should provide financial, technical and legal support to those member-states that need it.

- The EU can also help to improve co-operation between law enforcement agencies in member-states. EU bodies like Europol enable national agencies to work together more effectively than they could in the past; but rules on cross-border police co-operation need to be modernised.

- The interoperability of law-enforcement and migration databases was a priority for the outgoing Commission, but is still a long way from being achieved. The EU and the member-states must invest more in this area.

- The EU also needs to invest in new technology to fight crime. It must not be outpaced by those who use technology to facilitate crime. At the same time, it must ensure that technology is employed in accordance with European values and fundamental rights. The EU, member-states and the private sector need to work together to ensure that technology is used for beneficial purposes.

- The EU needs a fully-fledged migration management system, with real-time monitoring and a single point of co-ordination and decision-making, based on robust intelligence collection.

- The Common European Asylum System is in need of reform, to ensure that it is not abused but protects genuine refugees. The EU needs migration and asylum policies that are effective, efficient and fast.

- The EU needs to strengthen its partnerships with third countries, starting with those that are Schengen members, but not EU members. They should be able to participate in all new measures in the EU’s Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. Third countries in the Western Balkans, and others such as the UK after Brexit, should be able to participate in migration and security co-operation whenever possible. The EU should continue to invest in co-operation with neighbours to the east and south, and with like-minded democracies further afield.

- Migration, security and justice must be properly funded in the EU’s next seven-year budget cycle. Some programmes are currently allocated too much money; others, including Europol, have too little for the tasks set for them.

In March 2016, while the European Union was still reeling from the fallout from its migration and security crises, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said that the EU needed to “go back to Schengen” – and launched a plan explaining how to do so.1 The implication was that, in the midst of its worst refugee crisis since the Second World War and a string of terrorist attacks in 2015 and early 2016, the EU had somehow lost track of how its borderless area should work.

Schengen did not collapse under the pressure of those twin challenges, but the idea that the system must be ‘reset’ persists in Brussels and national capitals. French President Emmanuel Macron wrote in March 2019 of the need to rethink the Schengen area fundamentally.2 Likewise, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Germany’s defence minister and leader of Angela Merkel’s CDU, has said the EU should “complete” Schengen.3

It is almost 35 years since the Schengen agreement, named after the town in Luxembourg where it was signed, paved the way for a Europe without borders. Despite multiple challenges, Schengen co-operation remains a boon for the people and businesses of its member countries, despite the controls in place on a limited number of borders between member-states.4 The fact that the system managed to pull through despite the unprecedented migratory inflows of 2015 and the terrorist attacks in Brussels, Paris and Berlin proves its resilience. But while Schengen may not need a complete overhaul, it could certainly do with a boost. As the EU’s new leadership takes office, this paper examines what the Union could do to ensure that Schengen continues to be one of the EU’s most popular achievements.5

What is Schengen? Or, why Schengen is more than Schengen

The Schengen agreement, which became operational in 1995, abolished internal borders between the countries that signed it. All EU member-states except Britain and Ireland are now part of Schengen; while Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland are members of Schengen but not of the EU. Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania are legally already part of the Schengen area but are still waiting for border controls to be lifted, once they fulfil all the technical conditions and a political decision to that effect has been taken.6 Some 400 million people live within the Schengen area. The vast majority of Schengen’s external frontier is coastline – it has 42,673 kilometres of sea border, much of it on the Mediterranean, compared with 7,721 kilometres of land border. There are a total of 1,800 official points of entry along those borders.

The abolition of borders has made it easier for people and goods to move freely across Europe. But three years ago, Europe’s darling became its bête noire: in the absence of either solutions to the conflicts in the EU’s neighbourhood that triggered unprecedented migratory flows to Europe, or fully-fledged common European security and migration policies, Schengen’s open borders became a major source of disunity between member-states.7

And yet, the Schengen agreement has successfully weathered these challenges because of two key ingredients: it involves trade-offs, so that benefits and burdens are shared; and it presupposes a high degree of mutual trust between its members.

To produce the benefits of abolishing internal border controls, the Schengen system requires member-states to introduce so-called compensatory measures, such as common rules for the protection of external borders, exchange of law enforcement information, and police, customs and judicial co-operation. Such co-operation does involve costs for member-states as their administration and legal framework must be made compatible with Schengen. For example, they must hire additional border guards, and invest in airports, ports, new IT systems, and enhanced asylum processing capacity. The burden of implementing such measures will not necessarily be spread evenly.

The second key ingredient is trust. For member-states to operate in effect as one jurisdiction requires a degree of mutual trust that each will live up to their common responsibilities. This is why the EU conducts peer reviews, with the possibility of the re-introduction of internal border controls hanging over member-states like the sword of Damocles.8

The EU’s single market and the Schengen area developed in parallel in the 1990s. Goods, services and capital moved more freely within the Union; and EU countries progressively stopped checking people at the borders between them. Both law-abiding citizens and criminals became increasingly mobile. More people from different nationalities made use of the so-called ‘four freedoms’ to travel, study, marry, have children, enter into contracts and buy property in another country. Meanwhile, migrants and asylum-seekers have come to Europe, seeking prosperity or escaping unrest and other hardships in their home countries.

Successive treaties governing the EU have reflected these trends. When integrating the Schengen framework into EU law, the 1999 Amsterdam treaty stated that the EU should “maintain and develop the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice, in which the free movement of persons is assured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration”. Ten years later, the Lisbon treaty said that offering EU citizens an area of freedom, security and justice (AFSJ) without internal frontiers should be one of the EU’s main goals.9

The AFSJ is built on the same principles of a balance of benefits and burdens and of mutual trust as the original Schengen treaty, but it covers a much broader policy area. When leaders refer to the need to ‘reset’ or ‘complete’ Schengen, they are actually referring to the need to revise the whole AFSJ, as Schengen has in effect been turned into and absorbed by the AFSJ, with features such as the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) and Europol that were not part of the original Schengen regime. For all practical, and political, purposes they have become one and the same.

An area without internal borders cannot function, however, unless it has a common approach to who should be allowed in and what to do with those facing judicial proceedings in a member-state other than their own. That is why the EU has (at least some sort of) a common migration and asylum policy and mechanisms to facilitate judicial co-operation between its member-states – not because this was part of the founding fathers’ dreams when they built the bloc.

The EU does not need to ‘go back to Schengen’, as the outgoing Commission’s mantra has it. Even when the bloc’s migration quarrels were at their worst, Schengen never actually ‘disappeared’ or ‘stopped’. But the EU does need to make sure that all Schengen members understand that being part of the passport-free area comes with obligations as well as advantages. It is time to make those obligations clearer and guarantee that no Schengen country gets away with breaching them. This is by no means an easy task, as the EU learned the hard way when the Commission tried, unsuccessfully, to introduce mandatory migrant quotas in 2016. To strengthen Schengen, EU leaders do not need new grand designs. They just need to tighten the nuts and bolts holding the current system together.

Ensuring existing commitments are implemented

An area without internal frontiers is only as strong and resilient as its weakest link. But not all member-states have the same resources. Nor do they have the same administrative capacity to implement new EU laws, or to introduce new IT systems. Implementation is already the single most important challenge for the AFSJ. With new laws and regulations being adopted and new IT systems being developed, that challenge will only increase.

An area without internal frontiers is only as strong and resilient as its weakest link.

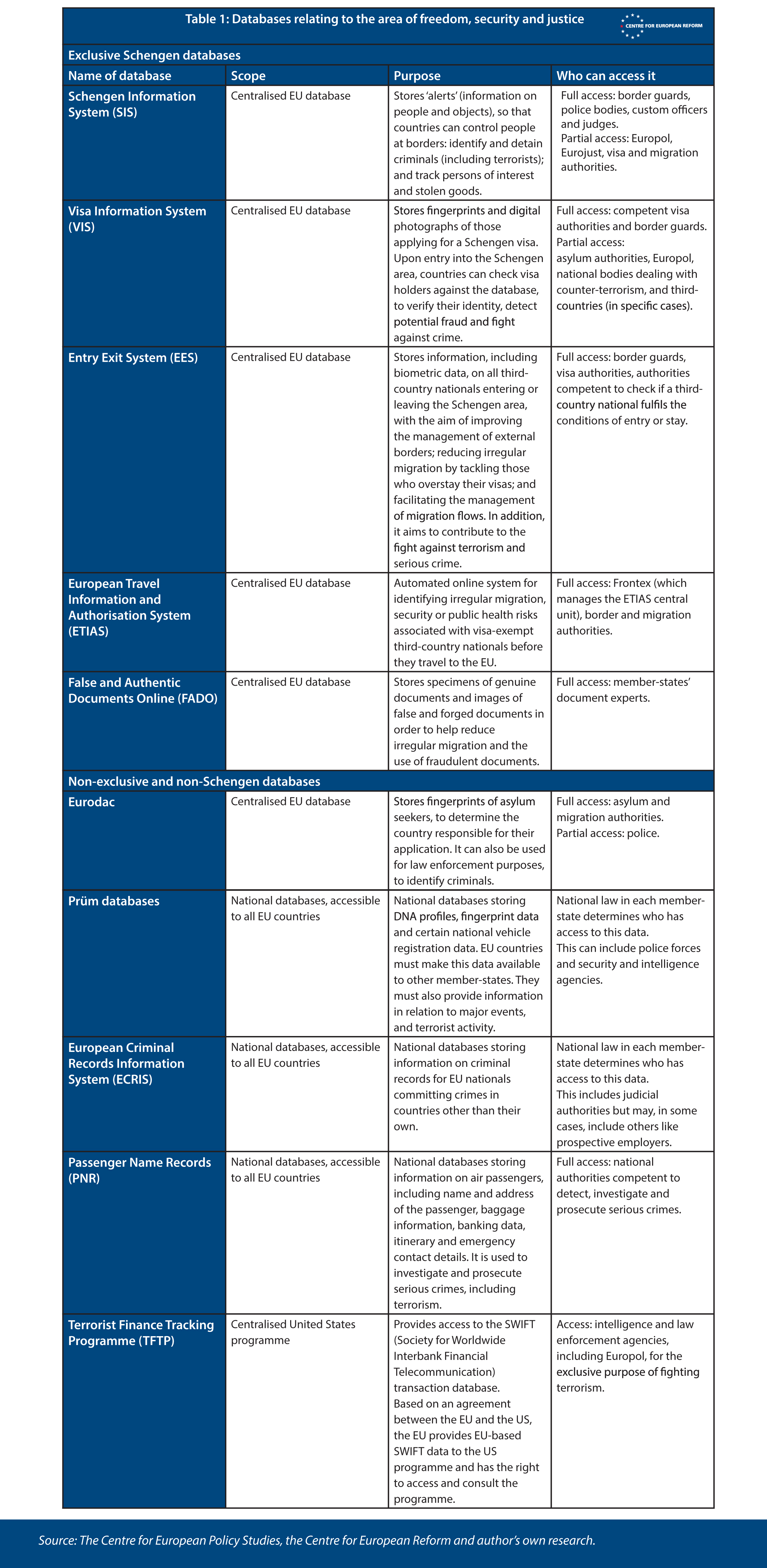

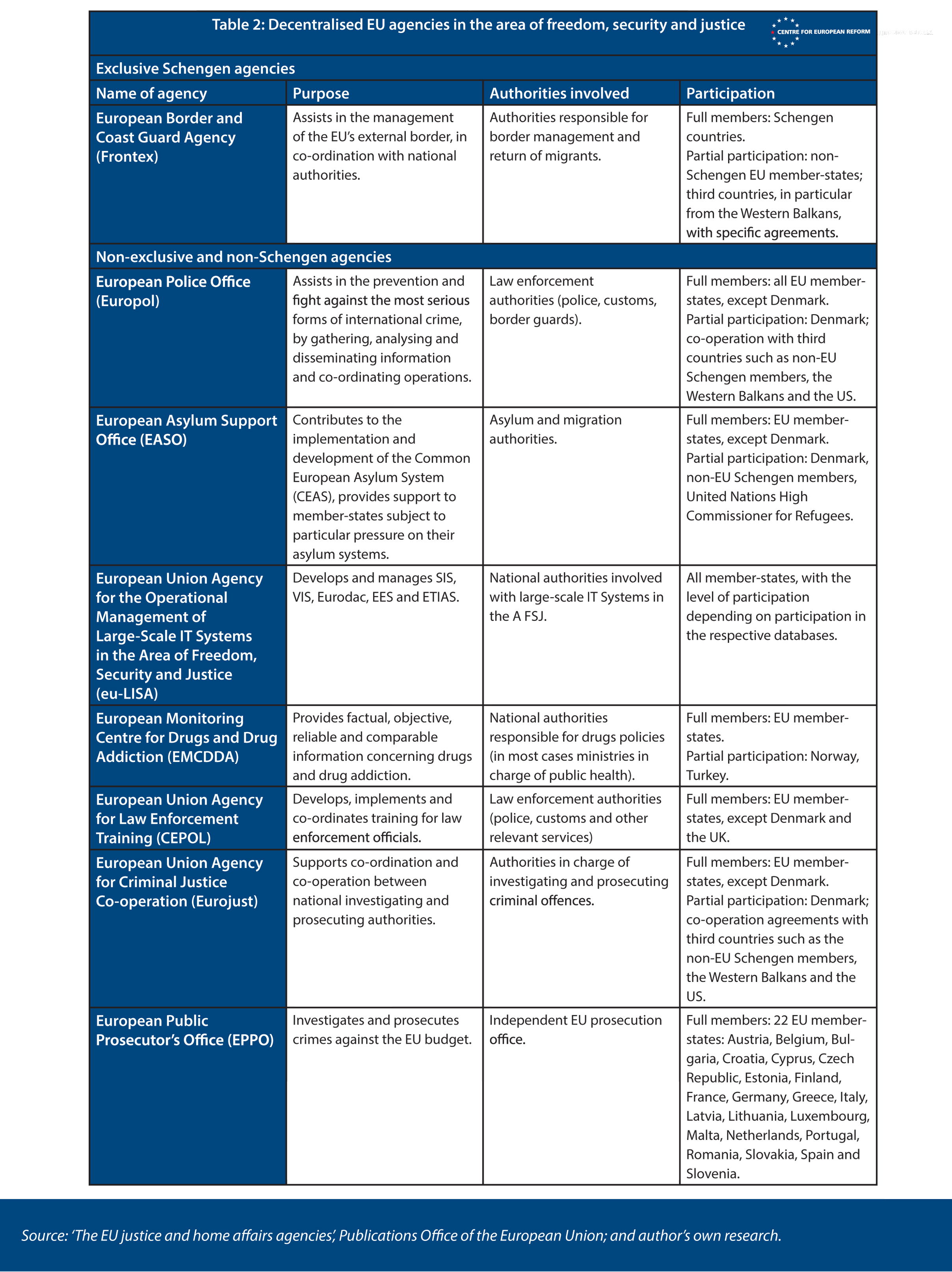

Despite what populists and other critics say, the EU has been quite successful in applying these obligations over the past 20 years, even as their number has grown. The original Schengen agreement contained 142 articles. The AFSJ now comprises dozens of regulations, directives and decisions, with thousands of articles. Initially, the system relied on just two databases – the Schengen Information System (SIS) and Eurodac, a database storing the fingerprints of asylum seekers. There are now ten databases and information exchange systems (see Table 1). The Schengen area’s infrastructure has also grown from one office specialising in tackling the illicit drug trade to eight separate decentralised agencies (see Table 2).

The less tangible but no less vital ingredient for the effective functioning of Schengen is trust. Without trust, member-states would struggle to co-operate in a way that ensures that the system works correctly and uniformly, for example through extradition or mutual recognition of judicial decisions.

The EU should encourage partners with greater capacities to pool equipment, know-how and resources with others.

To foster trust, the EU has used three different strategies: it has harmonised rules across the continent; it has built a number of common tools like databases and agencies; and it has set up peer review and monitoring schemes. The Union has traditionally focused on the first two of these strategies, to the detriment of peer review and monitoring of border control and law enforcement. Although the so-called Schengen evaluations have been part of the system since its inception, there is still no systematic and effective joint monitoring. A fair, EU-wide mechanism to evaluate national judicial systems, border guard capabilities, fingerprinting or screening and processing systems could have partly mitigated the Union’s recent problems with migration management in Greece, the rule of law and independence of the judiciary in Hungary and Poland, or inconsistent understanding and application of the EAW in a number of member-states.10 To be credible, these peer review systems cannot be geared to singling out specific countries. Instead, they should introduce criteria to ensure that all member-states are tested against the same benchmarks, regularly and objectively. No treaty change is required: Article 70 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) allows member-states to conduct objective evaluations of how EU governments are applying EU AFSJ rules, and in particular whether national authorities are fully and accurately implementing judicial decisions made in other member-states.11

EU support to member-states

When the EU identifies inconsistencies or shortcomings in member-states’ implementation of EU rules, its institutions cannot address them overnight, but they can provide financial, technical and legal support to those member-states that need it. The problem is that the implementation of agreed policies is less attractive to politicians than advocating reforms. Member-states will need to use a lot of resources and political capital to improve the way the AFSJ is implemented in practice.

The EU should lend a helping hand. It could, for example, help countries by building up their capabilities to tackle rapidly evolving technologies and threats. It could also despatch experts and equipment to member-states that require assistance in areas where they do not have the necessary resources, be it surveillance, tracking monetary flows, decryption, digital forensics, facial recognition or artificial intelligence (AI). Europol should be in charge of providing this ad-hoc support, and the EU should encourage member-states with greater capacities to pool their equipment, know-how and resources with those who are less well provided-for.

Teaming up

The EU can also help improve co-operation between those in charge of upholding the law in its member-states, be it police officers, customs officials or border guards. The EU has been very good at bringing together the law enforcement community, for example, in a way that member-states have not. Some national law enforcement agencies now communicate more through Europol, the EU’s police agency, than they used to between themselves. This ‘integrated approach to security’ is crucial if the EU is to be a credible security provider. It should be at the heart of a long overdue modernisation of the legal framework governing cross-border police co-operation, which has been untouched for 20 years. Rules on cross-border hot pursuit differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction; information exchanged bilaterally between two member states is not necessarily shared with Europol or cross-checked with EU databases. The legal framework needs to adapt to evolving threats and link up with the latest generation of EU agencies and databases.

Communication between law enforcement and migration authorities has improved tremendously thanks to the vast array of databases the EU has built in recent years. They are still not linked together, however. This makes it harder for the Union and its member-states to deal with cross-border, multi-faceted security risks. In an effort to plug these gaps, the Council of Ministers and the Juncker Commission made interoperability of the EU’s databases a priority. Although the bloc has passed laws to improve database links, communication between the EU’s and member-states’ databases is still not ideal. The EU should work on integrating systems like Prüm (national databases storing DNA, fingerprints and vehicle registration data) and Passenger Name Record (PNR – national databases containing information on air passengers) as well as customs databases and financial investigation tools. Managing interoperable databases is fiendishly difficult. So the EU and its member-states will need to devote considerable resources to improve the communication between databases – as politically unappealing as the implementation of IT systems might sound.

The EU has brought together the law enforcement community in a way that member-states have not.

Data collection and sharing is not only useful for catching criminals. It is also important for understanding crime and security trends and to inform the EU’s work on prevention. But that requires the ability to analyse vast amounts of data. To that end, the EU should allocate more resources to monitoring current events and anticipating future crises. Some EU agencies and bodies are already doing a good job in tracking trends and building forecasts. Europol, for example, regularly releases a threat assessment.12 Frontex, the EU’s border agency, conducts regular analyses examining potential risks to the EU’s external borders.13 And the Commission’s Directorate General for migration and home affairs (DG HOME) has a whole team devoted to using data to provide the EU with sound risk assessments.14 The EU should foster a similar approach in other departments, and strive for joint assessments wherever possible.

Investing in the future

Technological progress provides both challenges and opportunities for law enforcement, the judiciary and border control. Technology knows no boundaries, but the law inevitably does. This has led to previously unthinkable problems, like how to regulate the use of the internet when different jurisdictions have different views, and different ways of enforcing them. But new technologies also allow for novel solutions.

Policing borders with 10,000 new border guards in an EU-flagged uniform may have made sense ten years ago. But drones and facial recognition systems powered by artificial intelligence could, for example, prove more efficient than having border guards scattered across a border. They may also help to monitor particularly complex sea borders like those of the Greek islands, and to police mountain frontiers with limited resources.

The EU needs to realise the future lies in investing in innovation and technology, and harnessing and driving its potential in line with Europe’s values and fundamental rights. To achieve that, the EU’s different branches, including the newly created Commission department for defence industry and space, need to co-operate more closely. But the EU cannot do this alone. To ensure that it is not being outpaced by those that will use technology for nefarious ends, the Union needs to team up not only with national governments, but also, and perhaps most importantly, with researchers and companies in the private sector. Only if the EU pools the necessary funding and expertise will it be able to remain at the cutting edge of innovation in this area.

For the present, a joint ‘innovation lab’ for the AFSJ, hosted by Europol, could co-ordinate these efforts; ultimately the aim should be to join forces with those responsible for defence innovation, as it makes sense to work to identify technology, such as facial recognition software or drones, that would be of value to both military and civilian security organisations. For that, the new European Commission should suggest a full overhaul of Europol’s mandate. In doing so, it will be important to define what is in line with the EU’s rules on data protection, and more generally with European values. EU legislation can do its part, including in overcoming the different approaches that individual member-states might have; but actors like the European Data Protection Supervisor will interpret the legal framework day-to-day. On the basis of their interpretations, law enforcement agencies will be able to make the best use of what new technologies have to offer, without crossing any ethical lines.

The EU must partner with the private sector on innovation in order to harness new technology. But it also means that the member-states must ensure that companies uphold their responsibilities. Industry and businesses are responsible for keeping their clients safe. This includes making sure that criminals do not use social media and other computer platforms for illegal activities or to promote crime, terrorism or hatred. It also means that firms must protect critical infrastructure and safeguard the financial system from abuse. Private companies failing to do so should bear the consequences. This is not about outsourcing state responsibilities to the private sector, but rather about companies’ responsibility to abide by the law. Impact assessments, a standard feature when designing policies and regulations across all industries, should include an analysis of security implications, including the role of the private sector.

Migration – the EU as first responder

The EU has put together a solid set of migration measures since its 2015 refugee crisis. These now need to be refined further to respond to the constantly developing challenges and patterns of legal and irregular migration. The EU needs to become even more flexible to be able to channel human resources, material assistance and funding quickly to prevent irregular flows and to assist countries and regions that are under pressure.

The Common European Asylum System is undoubtedly in need of reform.

One element of the EU’s response to migration flows should be a fully-fledged EU migration management system. Such a system would incorporate real-time monitoring, early warning and a single point of co-ordination and decision-making across EU institutions and agencies. For it to work, the EU would need to collect robust intelligence so that it can provide a sound, up-to-date picture of the situation on the ground, including where timely intervention can avert crises long before they arrive at the external border. Under this system, all relevant EU departments and agencies would work closely together and with national governments.

All across the continent, it is the day-to-day responsibility of home affairs ministries to be prepared and trained when disaster strikes. It is time for the EU to have such a plan, and to be prepared for crisis management. There is no reason the EU should not be capable of it. The lessons learned in 2015 must lead to long-lasting change.15

Rethinking the migration process

The EU’s set of laws regulating different stages of the asylum process, known as the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), is undoubtedly in need of reform. Too often irregular migrants apply for asylum as a means of getting legal permission to be in the EU temporarily, because they know that this is, de facto, their best chance to stay in the EU.16 This diversion from the original purpose of an asylum system is unsustainable. The EU has been trying to overhaul the system for years, without success. At the heart of the debate is the Dublin regulation, a law that places the responsibility for dealing with asylum seekers on the country in which they first arrive. Although most irregular migrants and asylum seekers arrive by sea, it is not, as it may seem, the EU’s southern member-states alone that bear the heaviest burden. In fact, the EU countries that receive the highest number of asylum applications in relation to their population, in descending order, are Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Luxembourg, Germany, France, Belgium and Sweden, according to Eurostat. This unequal distribution of asylum applications satisfies no one. But neither does the remedy proposed by the European Commission in 2016. Its proposal to redistribute asylum seekers from their country of first arrival to all other member-states according to a system of mandatory quotas failed to gain the support of the required majority of member-states.

The EU needs to look at the migration process as a whole, from entry, be it regular or irregular, through to either integration or return. Neither the Dublin system, still less a mandatory quota scheme, will provide a silver bullet. The future EU asylum acquis should preserve the right to apply for protection, but determine more efficiently and quickly who is genuinely in need of protection, and return those who are not to their home country or the transit country in which they should have sought asylum. The bloc should focus on building migration and asylum policies that are effective, efficient and fast. This would be good not only for over-burdened national authorities but especially for migrants and asylum seekers, whose lives have too often been put on hold for years while national administrations struggle to process their applications. The EU and its member-states will need to have uncomfortable but necessary discussions on how to prevent irregular migration, and on how to return, readmit and integrate migrants.

Mainstreaming co-operation with third countries

The crisis of 2015-16 showed the EU cannot solve its migration and security challenges on its own. To deliver its policy objectives, the EU is increasingly reliant on its partners, especially those in its immediate vicinity. But this co-operation is not as efficient as it could be.

Co-operation on migration and security with countries in the eastern and southern neighbourhoods will remain crucial.

First and foremost, the Union should strengthen its partnership with countries that are members of Schengen but not the EU – Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The EU should offer them a new deal: they should be able to participate in all AFSJ measures, like Europol or Eurojust, with full judicial oversight. Their current level of participation is based on the original Schengen rules. For the EU-28, the AFSJ has absorbed the original set of Schengen rules and greatly expanded them. Not being EU members, the four Schengen associated members have been left out of this transformation. This not only leaves them out of important developments, but also creates a security gap within the free travel area. There is no justification, other than an antiquated, legalistic one, as to why these countries should not be full members of the AFSJ, as they are part of Schengen already.

The other group of countries that the EU should do a better job of cultivating is the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Kosovo). While these countries are in a holding pattern for entry to the EU, the Union should look to include them in its migration and security policies, whenever and wherever possible, particularly when it comes to operational measures or exchanging information. As security co-operation generally benefits both sides, a similar type of co-operation should also be extended to post-Brexit Britain.

Co-operation with other countries in the neighbourhood, such as Ukraine, Turkey, Libya and Morocco, will remain crucial. The EU, either directly or by providing support and political clout to some of its member-states with traditionally strong links to individual partners, has invested substantially in co-operation with its immediate geographic neighbours. The underlying reason for this expanded co-operation is the realisation that the EU needs it to deliver on its migration and security policies. This has been most apparent in initiatives such as the March 2016 deal with Turkey, which stemmed the flows of irregular migrants to Greece, the training of the Libyan Coast Guard or financial support to Morocco.

Finally, the EU should do a better job in reaching out to like-minded democracies around the world, like the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan or South Korea. Despite their differences, the EU’s views on things like cyber offences, the ethics of artificial intelligence in law enforcement, the integrity of electoral systems or the law enforcement approach to disruptive technologies, are closer to these countries than they are to any others.17 This could, and should, translate into more sustained efforts to reinforce co-operation and align positions, including in international bodies like the UN or the lesser known, albeit highly influential, International Telecommunication Union.18

Projecting power in the international arena has always been a challenge for the EU, and the external aspects of justice and home affairs are no exception. When it comes to negotiating and enforcing return agreements with countries of origin and transit, ensuring big US-based tech players remove online terrorist content, or ensuring that foreign jurisdictions hand over electronic evidence, justice and home affairs departments often cannot muster the necessary leverage on their own. Other departments need to chip in, and co-ordination of external policy is key to ensure consistency. But Commission president-elect Ursula von der Leyen’s suggested structure for the new Commission will probably complicate things further. As it stands, her plan includes three commissioners-designate directly in charge of the EU’s external action (with commissioners for neighbourhood and enlargement, crisis management and international partnerships); at least three other key players to manage trade, the biggest EU bargaining chip, and dealings with Silicon Valley (the vice-president for the digital age, the commissioner for the internal market, the commissioner for trade); and, of course, a foreign policy boss (the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy). It is unclear how all the departments with some responsibility for aspects of the AFSJ will work together, how they will co-ordinate with the EU’s diplomatic service and who would report to whom. This is sure to make the EU’s actions abroad even trickier.

Better funding

Building innovative and more agile approaches to migration, security and justice will not come cheap. The EU-27 will have to agree to a proportionate allocation of funds in the EU’s 2021-2027 budget, or Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). While the proposed overall spending for justice and home affairs appears likely to cover the most pressing needs, the EU will still need to make some adjustments. For example, according to the revised financial statements for Frontex, the border agency will need around €2.2 billion less than initially planned. That money could go to Europol – its budget is too small for the agency to adequately carry out the tasks EU leaders’ have asked of it.19 Likewise, the funds managed by DG HOME need to be able to contribute to combat illegal migration abroad.20

Conclusion: Schengen, reloaded

Four years ago, it looked as though the Schengen system was about to collapse. In the end, it survived, perhaps against the odds. This does not mean the system is perfect, or that it does not need reform. As this paper has shown, there are many things that the EU can and should do to improve Schengen and ensure it remains sustainable and able to withstand the next shock.

Schengen and the AFSJ more broadly do not need a complete reset. But, to keep the borders open at a time of rising populism and nationalism in Europe, it is important that all Schengen countries understand and respect the commitments that come with membership of the system. Notably, all member-states need to do a better job in applying the rules. The EU can help them by co-ordinating their efforts and sending money and operational resources, but it will ultimately be up to these countries to comply with, and properly apply, Schengen’s rulebook. The EU should also become more resilient and better able to manage irregular migration and mixed flows of asylum seekers and economic migrants. This includes improving the efficiency of EU asylum rules, where a new approach is required to overcome the current deadlock.

The EU must exploit the potential of technological developments. This includes improving data collection and information sharing systems and boosting the EU’s analytical skills. Databases and national security agencies need to be better at communicating with each other, while also respecting the EU’s charter of fundamental rights. None of this will be easy. So the EU should allocate sufficient funds to invest in innovation and urge member-states to pool equipment, know-how and resources. Good working relationships both with third countries and the private sector will be crucial if the EU is to respond effectively to evolving security threats, like terrorism or hybrid threats.

In June, EU leaders laid out their priorities for the next five years.21 The first of these is ‘protecting citizens and freedoms’, precisely what the EU’s Area of Freedom, Security and Justice was built to do. To ensure that the AFSJ continues to deliver freedom and security for all Europeans, the new EU administration should devise a clear plan to ‘reload’ Schengen.22 Otherwise, the EU’s cherished passport-free travel area may not survive the next crisis.

2: Emmanuel Macron, ‘Dear Europe, Brexit is a lesson for all of us: It’s time for renewal’, The Guardian, El País, Die Welt, Il Corriere de la Sera and others, March 4th 2019.

3: Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, ‘Make Europe right now’, Die Welt, March 10th 2019.

4: Internal border controls are currently maintained on certain sections of the border and with varying intensity by Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway and Sweden.

5: Roughly two-thirds of Europeans think that Schengen is one of the EU’s main achievements. See European Commission, ‘Europeans’ perceptions of the Schengen Area’, Special Eurobarometer 474, December 2018.

6: Ireland and the UK have an opt-out from Schengen, and are not obliged to join.

7: Camino Mortera-Martínez, ‘Why Schengen matters and how to keep it: A five point plan’, CER policy brief, May 13th 2016.

8: A look into the 1990 convention implementing the Schengen agreement shows the importance of this safeguard; Article 2 paragraph 1 sets out the principle of open borders, and paragraph 2 allows for temporary re-introduction of controls (see ‘The Schengen acquis – Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985 between the governments of the states of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders’, June 19th 1990).

9: Treaty on European Union (TEU), Article 3, paragraph 2.

10: Camino Mortera-Martinez, ‘Catch me if you can: The European Arrest Warrant and the end of mutual trust’, CER insight, April 1st 2019.

11: Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), Article 70.

12: European Police Office, ‘Europol’s European Union serious and organised crime threat assessment 2017 (SOCTA)’, February 28th 2017.

13: Frontex, ‘Risk Analysis for 2019’, February 2017.

14: DG HOME’s Unit for Situational Awareness, Resilience and Data Management.

15: For possible scenarios see Elizabeth Collett and Camille Le Coz, ‘After the storm, learning from the EU response to the migration crisis’, Migration Policy Institute Europe, 2018. An earlier version of this report was commissioned by the General Secretariat of the Council to inform internal discussions with EU and national officials.

16: According to EASO, the EU´s asylum support office, the total recognition rate for EU and Schengen countries in first instance (refugee status, subsidiary protection and national protection schemes) in 2018 was 39 per cent, down by 7 percentage points from the previous year.

17: See, for example, ‘Foreign ministers’ communiqué’, G7 foreign ministers’ meeting, April 6th 2019.

18: The International Telecommunication Union plays a crucial role in standard setting for new technologies like 5G, artificial intelligence, or connectivity in general.

19: European Council, ‘European Council conclusions’, October 18th 2018, paragraphs 3 and 9.

20: European Council, ‘European Council conclusions’, June 28th 2018, paragraph 9.

21: European Council, ‘A new strategic agenda 2019-2024’, June 2019.

22: Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), Article 68 entrusts the European Council with the “definition of the strategic guidelines for legislative and operational planning within the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice”.

Raoul Ueberecken, Director for Home Affairs at the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, November 2019

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU.

This paper examines some ideas that have been discussed at meetings of the Amato Group, a reflection group on EU justice and home affairs chaired by former Italian Prime Minister Giuliano Amato. The group is an initiative led by the CER and supported by the Open Societies European Policy Institute (OSEPI).

View press release

Download full publication

Comments