Why Europe needs legal migration and how to sell it

- The total number of migrants coming to Europe by sea has fallen by 90 per cent since the peak of the so-called refugee crisis in 2015. Yet the EU’s success in reducing arrivals has failed to silence the anti-immigration rhetoric of the populists.

- Moderate European politicians face a political challenge and a policy challenge, both of them tough: politically, with the European Parliament elections around the corner, they need to fight anti-migrant, populist forces, while they also have to devise policies to ensure that there is no repeat of the crisis.

- This task puts governments and mainstream politicians in a tricky position. Leaders tend either to ignore the problem or try to outpace the populists by tilting toward illiberal policies, allowing anti-migrant forces to own the debate. Neither choice is good for Europe.

- Migration to Europe will not and should not stop. The region’s relative prosperity will attract people from around the world for years to come. If managed correctly, migration tends to be positive-sum: it gives those who want to migrate an opportunity to improve their circumstances while providing more workers for host countries.

- It is the job of politicians to communicate both these facts to the public – while acknowledging that there is still some work to do if migration policies are to work for both migrants and host societies.

- EU leaders have made progress in dealing with the first element of any migration policy – curbing irregular arrivals and sending people with no right to stay back. But they must do better on the second part – providing alternative routes for those who still want to come, and whom European countries want to admit. Politicians should take a four-step approach to dealing with migration.

- First, they should explain that the EU has successfully reduced arrivals in Europe through improved border controls, more cash for countries of origin and transit, and better deals with partners. But they should also point out that this is not enough if EU migration policies are to be sustainable in the long term. The EU needs to find a way to allow some migrants in, without risking either their lives, the stability of the host country, or the integrity of the EU’s Schengen area.

- Second, leaders should accept that no government would be able to stop migration completely, even if it wanted to. Instead, governments should learn how to manage. It will not be easy to find a consensus among member-states on what to do with asylum seekers. But the question of economic migration is comparatively less complex. There are no internationally binding rules that the EU must follow when deciding what to do about those seeking to move and work in Europe.

- Third, EU leaders should make a nuanced case for legal migration. Well-managed migration can raise tax revenues, which can then be spent on ageing populations. The EU is the most rapidly ageing region in the world, after Japan. But economic and demographic arguments alone will not reverse current anti-immigration sentiments. A powerful counter-narrative is necessary to answer populist and far-right groups, which wield migration as a weapon in their fight against the EU’s liberal identity.

- Fourth, European leaders should find new ways to bring people in – without forgetting the trade-offs. The EU has not managed to set-up a common European system to bring migrants legally into Europe, and it may never do so. A more realistic way for the EU to get involved would be for it to support the implementation of bilateral projects between member-states and third countries, with a focus on medium-skilled migration.

- Such projects would help with the training of migrants in professions that require moderate levels of literacy, like nursing or hospitality management. The EU could help those projects either by disbursing money; or by ensuring that diplomas from partner countries are recognised across the bloc.

Migration is inevitable. Sooner or later, European leaders will need to drop the pretence that it can be stopped. Europe also needs migrants to supplement its ageing labour force. But European migration policy has fallen hostage to populism. Anti-migrant feeling is on the rise, and moderate politicians have been weak at making the argument for migration. With European Parliament elections around the corner, leaders should not default to vote-winning policies of migration containment and control. Of course, they must continue to make sure that borders remain secure and that people not authorised to enter or remain in Europe – so-called irregular migrants – are properly managed. But leaders must do more to convince voters that migration is good for them, or, at least, not as bad as populists say it is.

Although the total number of migrants arriving by sea has fallen by 90 per cent since the peak of the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, the EU’s response to migration is still driven by reflex responses to populist rhetoric.1 This is unsurprising. Governments in Hungary, Italy and Poland have been elected in part because of their anti-migrant and eurosceptic ideas. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has faced her worst political crisis to date because of migration disputes with her Bavarian sister party, the CSU. Other European governments, such as those in Austria or Denmark, include or rely on anti-migrant parties. And the Central and Eastern European member-states have effectively refused to take in refugees.

So far, EU policies have mainly focused on the ‘control’ aspect of migration: border management, returns and trying to address the root causes of migration.

But there is another pillar to migration policy – bringing in and retaining people who are needed in the EU, who will bring social benefits with them. This means integrating migrants into host countries and setting up workable alternatives to irregular migration. The EU has neglected this, due to a lack of consensus among member-states. Major disagreements remain on how to distribute asylum seekers across the EU and how to build a pan-European system for legal economic migration.

To win public support, the EU’s migration policies must serve both migrants and European citizens. To achieve this, EU leaders need to look beyond short-term solutions focused on shutting down borders and outsourcing controls to non-European countries. This policy brief makes the political and economic case for setting up more effective legal routes for migrants to enter Europe; explains how this can be done in practice; and considers the trade-offs facing European governments when dealing with legal migration. While legal migration will not, in itself, eliminate irregular migration, improved routes to Europe would help protect the continent’s security, while upholding European values and boosting the economy.

Ultimately, this brief aims to guide politicians who are formulating migration policy in a space that has been dominated by the likes of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Italy’s Matteo Salvini and US President Donald Trump. If politicians who support a pragmatic approach to migration do not make their case forcefully, they risk being drowned out by those who demonise migrants. The following four steps can help them to frame the migration debate.

One: Explain that although action to reduce irregular arrivals is necessary, other approaches are needed too

In 2015, over one million migrants and refugees arrived in Europe irregularly, an unprecedented increase of 370 per cent in just a year.2 The majority of them came from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.3 Since then, the number of arrivals has fallen significantly each year, as have the number of dead or missing – but so far this year, over 100,000 refugees and migrants have reached Europe by sea, and a further 2,000 people have died or gone missing on their journey.4 An additional 6,400 people arrived in Europe by land. Over half of those crossing to Europe by sea in 2018 have arrived in Spain; and at least 43,000 of them came from the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa.5

The EU’s response to the refugee crisis has been to reduce the number of people reaching the continent and to send back those who arrive on European shores and do not qualify for asylum. By making it more difficult for people to get to Europe, the EU hopes to both relieve the strain that uncontrolled arrivals put on receiving countries, and to counter anti-immigration and eurosceptic forces. Advocates of this idea also argue that stricter border controls and return policies give asylum seekers a higher chance of having their application assessed fairly and quickly. The EU has pursued several strategies to secure its borders.

One approach has been to beef up border security. The strengthened European Border and Coast Guard Agency (previously called Frontex) supports frontline member-states in their efforts to prevent irregular access to the EU’s passport-free Schengen area. Frontex helps EU countries by funding vessels, aircraft and other vehicles. The European Commission plans to increase the powers and mandate of Frontex, to cultivate a fully-fledged EU border force. In his State of the Union speech on September 12th 2018, Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker announced plans for 10,000 new European border guards by 2020, who would work at the EU’s border and also with third countries. Frontex’s budget will increase to €11.3 billion by 2027, so that the agency can purchase its own equipment rather than relying on member-states.6

The EU has also tried to improve its poor record of returning irregular migrants. Last year, only one-third of the 516,000 people that member-states ordered to leave actually left the EU.7 Returning rejected asylum seekers and irregular migrants to their countries of origin or transit is arguably the most difficult part of any domestic migration policy, as it requires procedures for verifying the person’s identity and ensuring their safe return. That is why trying to secure the help of origin and transit countries has been central to the EU’s return strategy.8

The EU has struck international readmission agreements in an effort to increase the number of migrants who are returned to their countries of origin. Currently, the bloc has 17 agreements in place and is negotiating a further six.9 These are not without problems: public opinion in migrant-sending countries can be hostile, as people view the deals as an obstacle to their free right to migrate. Because of how difficult it has become to convince countries to sign this sort of deal, the EU has instead set up what it calls ‘practical co-operation’ schemes to return people to places like Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Ethiopia. But without a formal agreement to ensure that returns follow strict human rights standards, these schemes risk becoming unaccountable – not least to the European Parliament. The EU has also been striking other types of deals to keep migrants out. In March 2016, it signed a deal with Turkey to return some categories of migrants and asylum seekers to Turkish soil and stop departures from the Turkish coast. In 2017, the EU agreed to help the Libyan authorities stop and return migrant boats, with Italy playing a key role. In June 2017, the EU’s chief diplomat, Federica Mogherini, praised the EU for assisting with the voluntary return of over 4,000 people from Libya to their countries of origin.10 Despite questions about the legality and morality of these deals (international law forbids countries from sending asylum seekers back to unsafe places and conditions in Libya for refugees and migrants are dire),11 both seem to have helped curb arrivals to Greece and Italy.

The EU has also signed migration ‘compacts’ – international agreements to boost co-operation on migration policies – with five ‘priority’ countries: Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal. It has also intensified its engagement with six others: Afghanistan, Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Guinea, Nigeria and Pakistan. While these deals are not restricted to co-operation on returns (the EU paid €34 million to help Afghans stranded in Iran and Pakistan, for instance),12 help with readmission is a crucial component. For example, in April of last year, the EU introduced an electronic platform for processing readmission applications in Pakistan (with which the EU has a readmission agreement), for use by European member-states and the Pakistani government.

The EU has been trying to address the root causes of migration, mostly by sending money to countries of origin and transit. In 2015, the EU launched the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, worth €4 billion. The Fund aims to help African governments to manage flows of migrants and also foster political stability and economic growth.

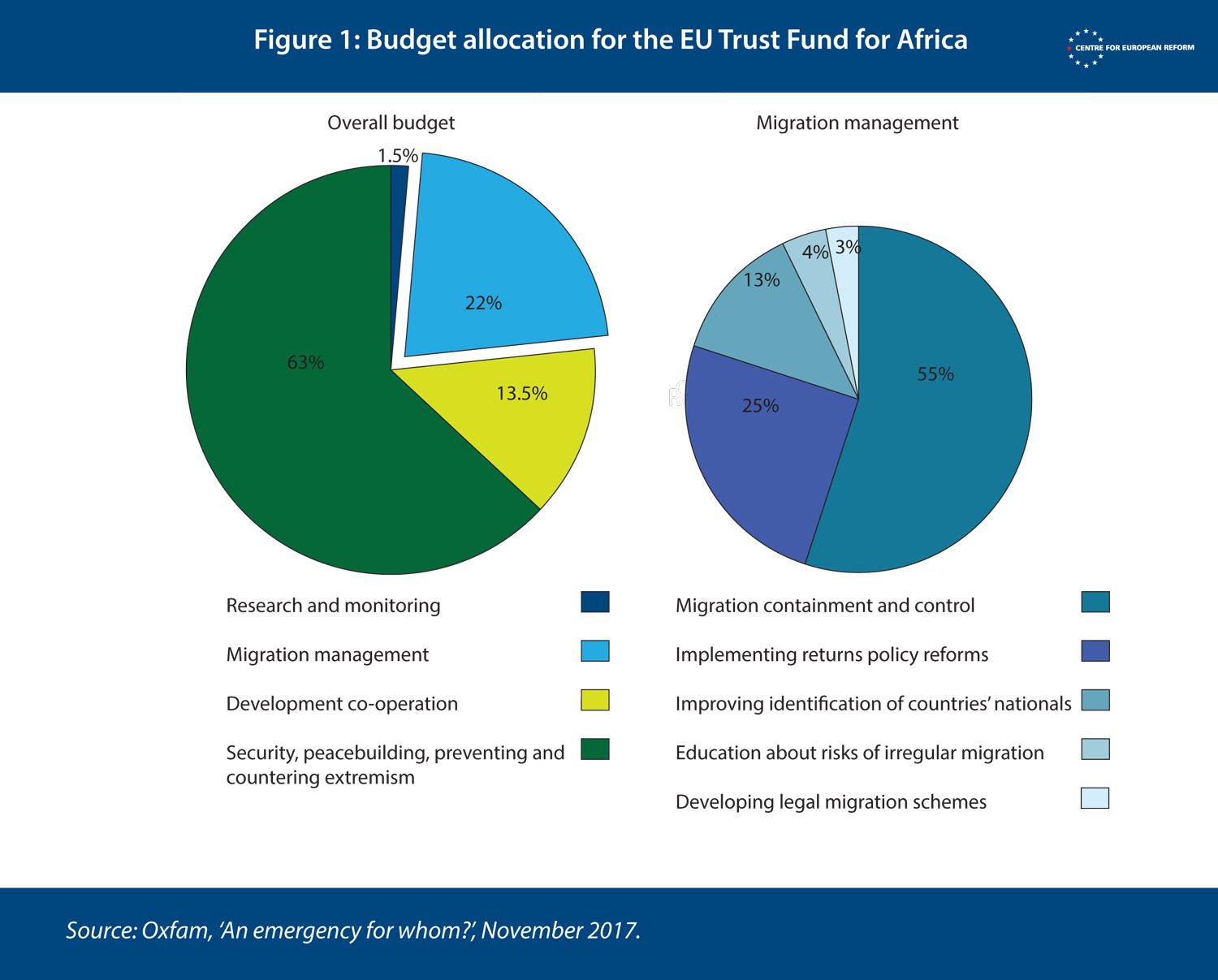

So far, the EU has promised to fund 146 projects under this scheme. Some of them seek to improve the labour market in target countries by, for example, reducing youth and female unemployment rates.13 Other projects provide basic needs, like food and healthcare.14 Migration and border management projects account for almost a quarter of the fund’s budget, and these largely focus on prevention and control. Of the amount allocated to migration management, 55 per cent is assigned to containment and control, 25 per cent to implementing returns policy reforms, 13 per cent to improving the identification of countries’ nationals, and 4 per cent to explaining the risks of irregular migration to local populations in sending and transit countries. Just 3 per cent is devoted to developing legal migration schemes both within Africa and towards Europe.15

The logic behind the Emergency Trust Fund appears to be sound: funding for policies to raise domestic employment and manage borders. The hope is that this will, in turn, reduce migration to Europe. But this approach has a number of flaws.

First, by explicitly tying aid to migration management, the EU’s highly regarded development policies risk becoming vulnerable to political pressure, particularly anti-immigration rhetoric. The EU prides itself on being the world’s top aid provider, which, in turn, allows it to be a global norm-setter, by making support conditional upon respect for fundamental rights and the rule of law. This, of course, takes time – the EU follows long and bureaucratic procedures so that all boxes are ticked before releasing funds. But the Fund is designed in a way that allows the Commission to disburse funds swiftly in the case of a political crisis, sidestepping the necessary checks if needs be. This means that the Fund could be used to pay for less-than-optimal migration control projects, at the behest of political leaders – be they Emmanuel Macron or Matteo Salvini.

Second, the EU’s shift to migration control has alienated partners, in Africa and elsewhere. The Fund’s lack of clear eligibility criteria has provoked criticism from non-priority countries as well as from the European Court of Auditors, and may prove counter-productive.16 In February 2017, the EU expanded the Trust Fund to Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Guinea, with little justification, leading some to believe that the selection was politically motivated. One senior African official from a non-priority country remarked: “It’s clear that the more irregular citizens you have in Europe, the faster you’ll receive funding from the trust. So we’ll let them leave”.17

Finally, evidence suggests that improving economic conditions in source countries can actually increase migration. Emigration rates are much higher in middle-income countries than in poorer ones.18 Higher incomes lead to increased aspirations, and mean that people are more likely to be able to afford the journey, and the cost of starting a new life elsewhere. And declining child mortality rates combine with high fertility rates to create a booming working age population.19 The International Monetary Fund estimates that in order to meet the employment needs of African populations, an additional 18 million new jobs would need to be created annually for the next 25 years.20

The EU’s migration strategy has been successful if results are measured in terms of lower irregular migrant arrivals. But this fails to take into account the reality: people will inevitably come to Europe, regardless of borders and peril. The EU needs to find a way to allow them in, without risking their lives; the stability of the host country; or the integrity of the EU’s Schengen area. This will require member-states to accept more integrated migration policies.

Two: Accept that no government will be able to stop migration, so leaders should learn how to manage it

At first glance, it may appear counter-intuitive that anti-immigration and populist rhetoric is on the rise in Europe, given that policy-makers have achieved a measure of success with their strategies for reducing irregular migration. But EU citizens are still anxious about the EU’s ability to deal with the migrants who are already in Europe – and those who may still want to come. The bloc’s initial struggle to get a grip on the refugee crisis undermined voters’ confidence in the EU’s ability to manage the inflow of migrants and asylum seekers. There is even evidence to suggest that the emphasis on quotas and restrictions feeds the anxiety-provoking narrative that migration needs to be strictly controlled, which in turn undermines public faith in governments’ ability to manage migration sensibly.21 These conditions have proved fertile ground for populist and anti-immigration politicians across Europe.

Ideally, EU leaders would be more open about the fact that people in poorer parts of the world will want to come to Europe, regardless of the obstacles; and that political instability, natural or man-made disasters and climate change will mean that the number of asylum seekers trying to reach the West will inevitably increase. But European voters have clearly shown they will not accept chaotic migration, so those opposed to the populists must embrace both border controls and an expansion of legal routes.

Hopes that the EU will soon be able to find a sustainable plan to manage asylum seekers are fading. EU institutions and the national capitals have been working on overhauling the EU’s common asylum system (CEAS), and its main law, the Dublin regulation. The regulation devised a system for assigning responsibility for asylum seekers reaching Europe, whereby it falls mainly on the country of first entry. But reform talks have so far largely stalled, as frontline and destination member-states disagree on the terms of the reform. Some EU countries, like Hungary and Poland, have refused to take in any asylum seekers at all.

Ultimately, distributing asylum seekers among EU member-states is not just a matter of quotas or courts. It is a question of convincing voters that Europe’s duty to help those fleeing conflict or facing repression is compatible with the host country’s prosperity and values. This is easier said than done. One idea would be to overhaul the global refugee pact, signed in 1951. Proponents of this solution argue that the laws which were suitable for those escaping the hardship of World War Two are no longer applicable. But most refugees are still fleeing the horrors of war and 85 per cent of the world’s refugees are hosted by developing countries, which bear a much heavier burden than Europe.22 The 2018 Global Compact on Refugees, a non-binding United Nations (UN) declaration, is a compromise attempt to update the international refugee system without undermining the safeguards in the 1951 convention. All EU countries have signed up to it and, if everything goes according to plan, it will be adopted by the UN before the end of the year.

The question of economic migration is comparatively less complex. There are no internationally binding rules that the EU must follow when deciding what to do about those seeking to move and work in Europe. The bloc and its member-states are, in principle, free to pursue whatever economic migration policies they see fit. So far, they have chosen to focus on curbing arrivals. But an approach to migration that includes legal pathways to Europe is necessary if the EU’s migration policies are to be sustainable in the long term, provide answers to Europe’s demographic crisis and give third countries an incentive to co-operate with the EU.

Three: Make the nuanced case for legal migration

Migration has been a key driver of population change in the EU since the 1990s. In 2016, immigration was the only reason the EU’s population increased. The EU’s birth rate has been falling for decades. And after Japan, the EU is the most rapidly ageing region in the world: the median age of EU citizens rose from 36.8 years to 42.6 years between 1996 and 2016. This is due to longer life expectancies but also lower fertility rates. Eurostat, the EU’s statistical office, expects population growth to slow even further and predicts that it will decline after 2045.23

This has big ramifications for the size of the EU’s working age population. The European Commission estimates that the EU’s labour force will shrink by 18 million over the period 2015-2035, a reduction of 7 per cent.24 The EU faces skills shortages and unfilled vacancies, particularly in the information and communications technology, health and engineering sectors, as well as in less skilled professions such as sales and driving.25 In the first quarter of 2018, the EU had at least 3.8 million unfilled jobs. Job vacancy rates differ across the bloc: this summer, 3.1 per cent of jobs were vacant in Belgium, as opposed to only 0.7 per cent in Greece.26

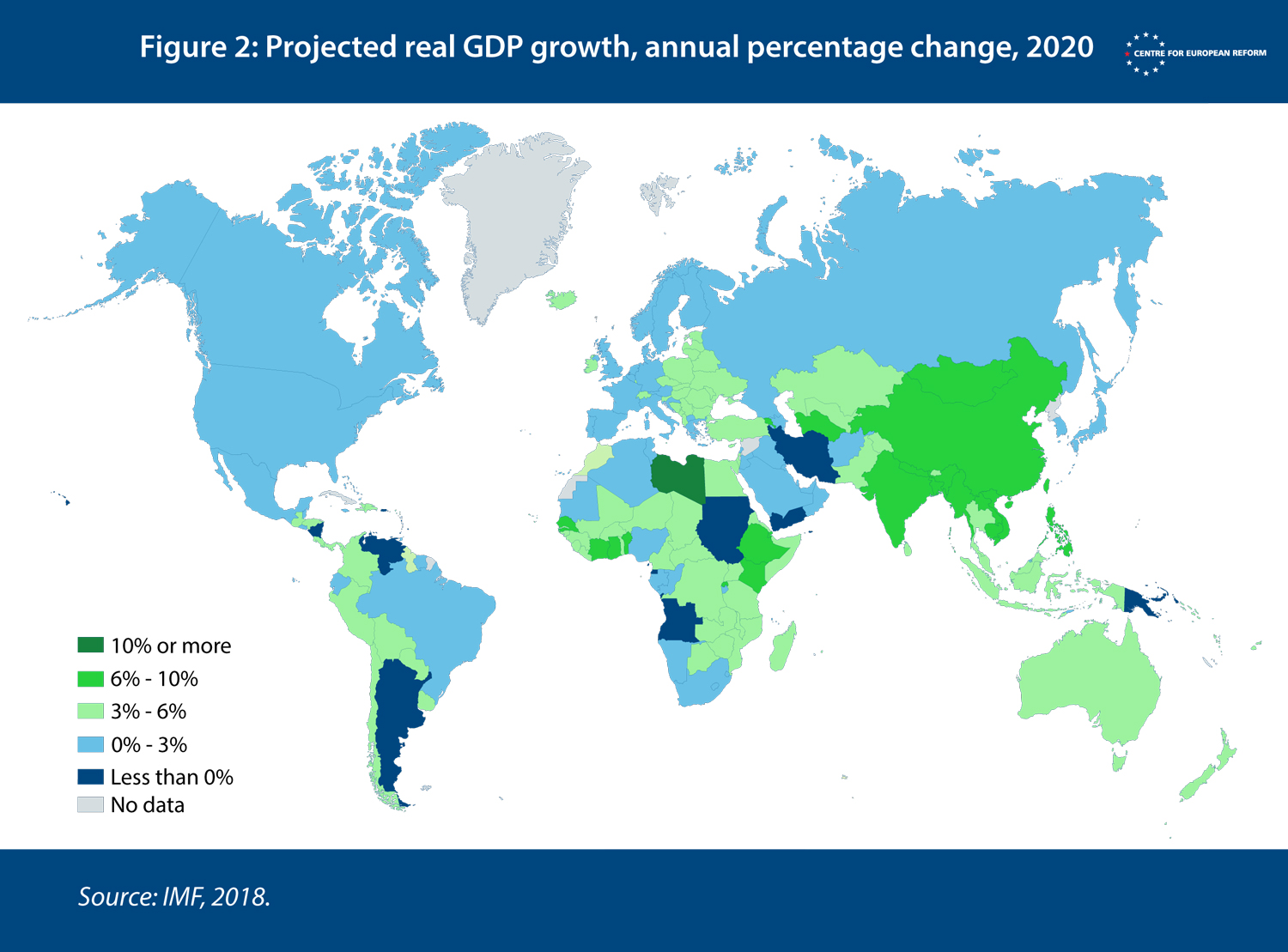

By contrast, Africa is experiencing a population boom. The continent’s population of 1.2 billion is expected to double by 2050. This is due to a large fall in child mortality, and a sustained high birth rate. The working-age population (aged 15-64) is expanding at an even faster rate. Africa has also been experiencing modest, albeit uneven, economic growth. In Sub-Saharan Africa, real GDP growth rose to 2.7 per cent in 2018, and is predicted to settle at 3.6 per cent by 2020.27 This growth is making African countries better off, but not sufficiently rich to retain their population; therefore rising GDP levels will most likely be accompanied by an increase of migration from Africa (see figures 2 and 3). In 2017, over nine million Africans lived in Europe.28 Lower living standards, political instability and climate change will continue to push Africans towards Europe, although most migrants from Africa will continue to move within the continent.

According to the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), only one in nine Africans leaving for OECD countries have qualifications beyond secondary school.29 However, many are multilingual and speak at least one European language. This is largely the legacy of colonialism.

Migration tends to be positive-sum: it gives those who want to migrate an opportunity to improve their circumstances while providing more workers for host countries, which in turn raises tax revenues, which can then be spent on ageing populations. And yet, economic and demographic arguments alone will not reverse the anti-immigration sentiment of much Western opinion.

To say that Europe needs migration may be factually right, but it is difficult to persuade Europeans of the merits of the case. Many believe that mis-managed migration is one of the biggest problems with globalisation, and that immigration leads to cultural and economic insecurity. Education alone will not shift public opinion. One study shows that people distrust official statistics on migration: they believe the government underestimates the amount of migrants in the country.30 Much of the opposition to migration stems from an intangible sense of threat – a sense of outsiders intruding. Research finds that this sense of perceived threat is linked to an individual’s sense of self-esteem and control over their surroundings.31 Likewise, people who lack trust in political institutions and leaders are more likely to oppose immigration.32 Those with low levels of trust are likely to be those who have not benefited from rapid socio-economic change.

It is also not clear that more legal migration would reduce irregular arrivals. Migrants who succeed in entering the EU without authorisation often do not satisfy the economic needs of member-states, as they tend to have lower levels of education.33 The EU will need to decide whether legal migration schemes should be open to lower-skilled migrants, or just those who are more highly-skilled. And, in order to plug skills gaps, the EU may need migrants from countries that are not a source of irregular migration. Additionally, to make legal migration effective and attractive, the EU must ensure that it matches the continent’s diverse national labour market needs.

There is no form of migration that pleases everybody. Low-skilled migration makes developed countries uncomfortable; and high-skilled migration is uncomfortable for developing countries, because they lose more productive workers. To be modestly successful, legal migration pathways need to take into account these concerns. This will require finding mutually beneficial arrangements that also give migrants the right incentives to use them. Such schemes have already been designed, but they have their costs and benefits.

Four: Find new ways to bring people in – without forgetting the trade-offs

Although there seems to be a growing consensus, in Brussels and elsewhere, that legal pathways are a necessary part of any sustainable migration policy, there is little agreement on what those routes should look like. Current EU-wide routes for legal migration are bureaucratic and complex, and at times contradictory. The Treaty on the Functioning of the EU says that the Union should develop common migration policies to ensure the effective management of flows,34 but member-states have resisted giving up control. Even in cases where concerted action makes sense, as in the case of mobility deals with neighbouring countries such as Morocco or Tunisia, the EU has not managed to get all member-states on board.35

As a result, there is no coherent approach to legal migration, and the 27 member-states operate their own, conflicting migration policies.36 The Commission can set up a framework for legal migration, but ultimately, it has no legal basis to move ahead without the support of member-states: it cannot force them to comply.

Some progress has been made on managing the migration of highly-skilled individuals, but the results are less than impressive. In 2009, the EU launched the ‘Blue Card’ scheme, which sought to replicate the US Green Card system. But unlike in America, Europe’s plan to attract white-collar workers has largely failed. The process for obtaining a Blue Card is long and complex; admission criteria are too restrictive; the scheme allows member-states to decide who should be given a Blue Card and introduce quotas; and once they obtain authorisation to come to Europe, Blue Card holders still face restrictions on their ability to move freely across the EU. As a result, most highly-skilled migrants choose to apply for national visas instead. Since 2009, only 68,580 people, or the equivalent of 0.01 per cent of the EU’s population have been granted a Blue Card visa. The overwhelming majority of them have gone to Germany.37

The EU has been trying for some time to make the Blue Card scheme more attractive by allowing migrants to move more freely across the bloc, and by granting them and their families improved residence rights. But negotiations between the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers have hit a wall. Setting up an EU-wide scheme to attract highly-skilled workers may be too ambitious for now. If member-states cannot agree on highly-skilled migration, there is little hope for consensus on low-skilled migration.

A more realistic way for the EU to get involved would be for it to support the implementation of projects between member-states and third countries, or between groups of member-states and third countries, with a focus on medium-skilled migration. Such projects would help with the training of migrants in professions that require moderate levels of literacy, like nursing or hospitality management. The EU could help those projects either by disbursing money via for instance, a dedicated fund; or by ensuring that diplomas from partner countries are recognised across the bloc.

This approach would respect national labour needs while still making sure that EU countries do not diverge too much in their policy on who is allowed into the Schengen area. Although politicians have resisted ceding sovereignty over migration, a recent poll by the European Commission found that two-thirds of respondents supported a common European migration policy.38

There are several ways to develop workable legal migration schemes. Perhaps the two most viable ideas are the European Commission’s legal migration pilot projects; and the economist Michael Clemens’ proposal for ‘global skill partnerships’ (GSP), a version of which is included in the UN Global Compact for Migration, signed in Morocco on December 10th 2018.

European Commission: Proposal on legal migration pilot projects

In September 2017, the European Commission announced that it would fund and co-ordinate pilot projects between willing member-states and migrant-sending countries to bring migrants into the Union.39 This is a novel – and contested – approach, as member-states argue that they have exclusive competence over legal migration. The idea is that national governments and businesses in selected EU member-states would identify labour shortages, and offer jobs to migrants in third countries so they could come to Europe legally. To be eligible, source countries should have a clean track record in co-operating with the EU on facilitating returns and cracking down on irregular migration.

The aim is for national authorities, economic actors like professional associations and chambers of commerce, NGOs and other civil society organisations to identify projects that could help meet labour market needs through legal migration. These could range from offering internships to language courses in migrants’ countries of origin, to schemes helping returning migrants to set up a business. If the Commission thinks the projects are helpful, it will pay for them. All member-states except for Denmark are allowed to apply for funding under this scheme, and yet, so far, none have.40

The Commission proposal for pilot schemes would allow EU countries to plug gaps in their labour markets, taking into account their specific needs and structures, while helping migrants to make their journey to Europe legally and safely. But in practice, things are not so straightforward. First, these projects are expensive and often difficult to implement. GIZ, Germany’s development agency, has been vocal on the complexity of putting together projects with an exclusive focus on matching migrant skills with labour market needs, as they need to be flexible, yet cheap enough to work. Second, member-states have been wary of giving the EU too much of a role in legal migration schemes. EU officials estimate that only three or four countries may eventually apply for funding. This is not only because of the sovereignty concerns mentioned above, but also due to Europe’s current migration narrative. Most EU leaders want the bloc to focus on cracking down on irregular migration before considering legal pathways to the continent, as voters are too concerned with the former to be open to the latter.

There are two reasons why this is misguided. First, reducing arrivals has so far done little to reassure the public and appease the populists. Anxiety about immigration does not correspond to the rate of immigration. If the EU has to wait until irregular migration is lowered to levels that anti-immigration advocates might consider ‘manageable’ (or, in the case of some populists, to zero), it will never get around to setting up realistic legal pathways to Europe. Second, legal migration cannot be an afterthought for EU policy-makers: many employers prefer to hire undocumented migrants precisely because they are cheaper and less likely to report harsh working conditions.41

Global skill partnerships

In January 2015, Michael Clemens published a proposal to solve the shortage of skilled workers in both developing and middle income regions through legal migration.42 Clemens argues that, within a few years, developed regions of the world, such as Western Europe, will need more trained professionals, such as nurses, than they can produce. Meanwhile, middle income regions like North Africa and Eastern Europe will also face an increasing shortage of skilled professionals due to brain drain and poor training.

This creates problems across the board: both developed and middle income countries need more nurses, but they either cannot find them or cannot afford to train them. Trained nurses in middle income countries are forced to migrate, while people in low-income jobs are unable to afford training and therefore never qualify.

Because nurses’ salaries are higher in developed countries and training costs are lower in middle income countries, Clemens came up with a proposal to use that gap to finance training for both migrants and non-migrants, at little or no cost to taxpayers. Below is an example of how this partnership would work for nurses trained in Moldova, some of whom may wish to move to Germany.

A version of global skill partnerships already exists: Germany has a program with Vietnam, to train Vietnamese nurses in care of the elderly. Australia has trained Pacific Islanders in sectors such as hospitality, education, tourism or construction since 2007.43 So far, 12,000 people from places like Papua New Guinea, Fiji or the Solomon Islands have benefited from this scheme, which provides Australian-standard training for those wanting to migrate but also for those wishing to stay in their home country. But less than 3 per cent of those trained have migrated to Australia or New Zealand, a fraction of the planned total.44 Unlike the Australian model, the German scheme does not intend to shape migration flows, as there is very little movement between Vietnam and Germany anyway.45 Both projects have been relatively successful, so some EU governments are analysing the costs and the way they are shared, to work out whether something similar would be feasible in their countries.

Much like the Commission proposal for pilot projects, the skill partnerships idea is workable and addresses the question of medium-to-low-skilled migration (Clemens proposes that training should not take more than one year). But the schemes depend on a range of other conditions to work properly: skill partnerships require full recognition of qualifications between countries; full involvement of the private sector (the Australian experience shows that properly functioning public-private partnerships are a crucial element of the scheme); ways to enforce repayment if graduates do not fulfil their work commitments; incentives for migrant workers to repay part of the fees of their student counterparts back at home; support from trade unions in both the destination and the sending countries, as they may fear the scheme could harm workers; and an initial expenditure from governments to get the scheme going. The skill partnerships idea also does not answer the question of how to connect demand and supply of unskilled migrant labourers.

Some of these problems could be solved by adapting the way the partnerships are financed. But other concerns may be harder to work around. For example, domestic workers may worry about ‘undercutting’ by foreign workers: indeed, an influx of trained workers from abroad may reduce wages in that sector. For GSP schemes to stand a chance, governments need to frame them carefully: as a certain level of migration is inevitable, host countries will benefit from providing migrants with skills that will help them integrate better, like speaking the language or being able to work as a certified technician. Receiving countries can then choose between paying to equip migrants with those skills once they arrive, which is expensive and takes time; or helping them to acquire those abilities before they set course for Europe (and perhaps even incentivise them to stay home instead).

Conclusion

European migration policy has fallen hostage to populism. Even the bloc’s success in reducing arrivals has failed to silence the anti-immigration rhetoric of the populists. This suggests the battle for ownership of the debate about migration policy is not just about facts, but also one of narrative. If liberal leaders are to win they must reject illiberal narratives, while acknowledging that migration creates winners and losers and, as such, no solution will be universally popular. The EU will not solve its migration woes through legal migration alone. But whichever solution European leaders choose to pursue must deliver incentives to both host societies and migrants alike. EU governments will never achieve this solely by sealing borders or distributing asylum seekers amongst themselves.

While EU leaders have made progress in dealing with the first element of any migration policy – curbing irregular arrivals and sending people back – they must do better on the second part: providing alternative routes for those who still want to come.

To ensure legal migration channels are beneficial for migrants and their host societies, they should take into account the specificities of national labour markets. National governments should use the EU’s offer to finance projects to equip migrants with the necessary skills to come and work in Europe and ensure those skills are useful, should they ever decide to return to their home countries. As taxpayers may not always be happy to pay for such projects, private investment could help, with migrants committing to work for a particular firm or sector for a certain period in order to pay for the training.

There are several ways to match Europe’s labour market needs with those of migrant-sending countries and, most importantly, with the needs and ambitions of migrants themselves. But all of them have trade-offs which leaders need to face when setting up legal migration pathways to Europe. Some people may not take kindly to seeing migrants coming in and taking jobs, even if their country struggles to fill vacancies. Similarly, some migrants may not want to go to countries where such programmes are on offer. Migration is not solely determined by economic or professional needs – other factors like culture and family also play a part. Migrants are more likely to go to countries where their networks are better established and which they perceive to be more open to diversity.

Liberal leaders are setting themselves up for failure if they try to convince voters that they have the answer to the EU’s complex migration dilemma. The hard truth is that nobody has. But there are less damaging and more efficient ways to manage migration. Better legal migration channels would be an improvement, provided they are planned correctly. Developing efficient legal migration routes should cease to be an afterthought, and should take place alongside border controls and return measures. If EU leaders continue to choose to focus solely on the more restrictive part of migration policy, they will play into the populists’ hands.

2: UNHCR, ‘Mediterranean Situation’, Operational Portal: Refugee Situations, November 6th 2018. Data analysis by authors.

3: UNHCR Tracks, ‘2015: The year of Europe’s refugee crisis’, December 8th 2015.

4: UNHCR, ‘Mediterranean Situation’, Operational portal: Refugee situations, December 10th 2018.

5: Syrians and Iraqis still account for 10 and 7 per cent of all arrivals, respectively. The UN provides a list of the ten most common countries of origin, which account for around 64,000 of the total arrivals.

6: The Commission’s grand plans for Frontex do not, however, have the support of all EU countries. In a recent summit, the 27 member countries said they wanted Frontex to be more efficient but only in so far as it does not encroach on the competences of national governments.

7: Eurostat, ‘Statistics on enforcement of immigration legislation’, June 2018.

8: Camino Mortera-Martinez, ‘Europe’s forgotten refugee crisis’, CER bulletin article, May 2017.

9: The EU has readmission agreements with (from least to most recent): Hong Kong, Macao, Sri Lanka, Albania, Russia, Ukraine, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Moldova, Pakistan, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Cape Verde. The EU is in negotiations with Algeria, Belarus, China, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Commission also launched readmission negotiations with Nigeria in October 2016.

10: European Commission, ‘Partnership Framework on Migration: Commission reports on results and lessons learnt one year on’, June 2017.

11: In November 2017, following an inquiry on the ground, the then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Raad Al Hussein, said that EU migration co-operation with Libya was inhumane. For more on the flaws of both the EU-Libya and the EU-Turkey deals see Luigi Scazzieri and John Springford, ‘How the EU and third countries can manage migration’, CER policy brief, November 2017, and Camino Mortera-Martinez, ‘Doomed: Five reasons why the EU-Turkish refugee deal will not work’, CER insight, March 2016.

12: European Council: ‘A new migration partnership framework’, November 2017; European Commission, Progress report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, May 2018.

13: For example, the Commission estimates that the Fund has helped create 3,000 jobs and 7,000 vocational training places in Ethiopia. European Commission, ‘Stemming irregular migration in northern and central Ethiopia’, 2018.

14: For instance, the EU has paid €25 million to boost food security in Mali; and it has sent €20 million to South Sudan to improve healthcare services.

15: Oxfam, ‘An emergency for whom?: The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – migratory routes and development aid in Africa’, November 2017.

16: Elizabeth Collett and Aliyyah Ahad, ‘EU migration partnerships: A work in progress’, Transatlantic Council on Migration, December 2017.

17: West African Observatory on Migration, ‘The Valletta Process: Round 2’, February 2017.

18: Hein de Haas, ‘Turning the tide? Why development will not stop migration’, Development and Change, November 15th 2007.

19: Michael Clemens and Hannah M. Postel, ‘Deterring emigration with foreign aid: An overview of evidence from low-income countries’, Center for Global Development, February 2018.

20: John May and Hans Groth, ‘Africa’s population: In search of a demographic dividend’, Project papers on demographic challenges, 2016.

21: Peter Andreas, Border Games: Policing the US-Mexico Divide, 2009, cited in Helen Dempster and Karen Hargrave, ‘Understanding public attitudes towards refugees and migrants’, ODI and Chatham House, June 2017.

22: UNHCR, ‘Global trends: Forced displacement in 2017’, June 2018.

23: Eurostat, ‘People in the EU – statistics on demographic changes’, December 2017.

24: European Commission, ‘Enhancing legal pathways to Europe: An indispensable part of a balanced and comprehensive migration policy’, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, September 12th 2018.

25: European Commission, ‘Enhancing legal pathways’, September 12th 2018.

26: Eurostat, Job vacancy statistics, September 2018.

27: World Bank, ‘Africa’s Pulse’, October 3rd 2018.

28: UN, ‘Number of international migrants by major area of destination and major area of origin’, 2017. African migration remains significantly higher within the continent: in the same year, over 19 million Africans were living in an African country other than their own.

29: UN-DESA and OECD, ‘World Migration in Figures’, October 2013. A recent study by the International Organisation for Migration looking at migrants arriving in Italy found that East Africans were comparatively more educated than others in the region. For example, 41 per cent of Eritreans had finished secondary school.

30: Ipsos Mori, ‘Perceptions and reality: public attitudes to immigration in Germany and Britain’, 2014.

31: IV Esses, LK Hamilton and D Gaucher, ‘The Global Refugee Crisis: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications for Improving Public Attitudes and Facilitating Refugee Resettlement’, Social Issues and Policy Review, 2017.

32: Lauren McLaren, ‘The cultural divide in Europe: migration, multiculturalism and political trust’, World Politics, April 2012.

33: Agnieszka Weinar, ‘Legal migration in the EU’s external policy: An objective or a bargaining chip?’ in Sergio Carrera et al, Pathways towards Legal Migration into the EU, CEPS, 2017.

34: Article 79 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

35: Only Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have signed the EU’s mobility partnership with Morocco; likewise, only Belgium, France, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom are part of the EU-Tunisia mobility treaty.

36: The UK has an opt-out from EU legal migration policies.

37: Eurostat, ‘EU Blue Cards by type of decision, occupation and citizenship’, July 2018. Based on the EU in its current composition, including Croatia. Luigi Scazzieri, ‘To manage migration, the EU needs to rethink its neighbourhood policy’, CER insight, May 2018.

38: European Commission, ‘First Results’ and ‘European Citizenship’, Standard Eurobarometer 89, Spring 2018.

39: European Commission, ‘Communication on the delivery of the European agenda on migration’, September 2017.

40: The Commission’s website provides a list of 23 public and private organisations from all across the EU looking for partners to apply for funding to projects on, inter alia, housing, micro-finance and mental health.

41: Thomas Spijkerboer, ‘A fresh start, or old wine in new bottles? The European Commission’s proposal for legal migration’, Border Criminologies, Oxford University, September 2017.

42: Michael Clemens, ‘Global Skill Partnerships: A proposal for technical training in a mobile world’, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, January 2015.

43: The so-called Australia-Pacific Training Coalition.

44: Michael Clemens, Colum Graham and Stephen Howes, ‘Skill Development and Regional Mobility: Lessons from the Australia-Pacific Technical College’, Journal of Development Studies, July 2015.

45: In 2010, there were an estimated 150,000 people from the Pacific islands living in Australia.

Camino Mortera-Martinez is a senior research fellow and Beth Oppenheim is a researcher at the Centre for European Reform, December 2018

View press release

This paper is part of a series on the future of Europe's migration and security policies supported by the Open Society European Policy Institute.