Securing Europe's medical supply chains against future shocks

European policy-makers should not give in to the temptation to use the COVID-19 pandemic to justify the forced onshoring of medical supply chains. Better options are available.

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted medical supply chains, leading some politicians to question Europe’s reliance on imports, particularly from China. To them, the solution is obvious: companies should be forced to make vital medical products in the EU rather than abroad. However, this is easier said than done, and pulling production into the EU does not necessarily leave the Union any less vulnerable to supply shocks. Being overly reliant on one location for vital products is a risk, whether the source is China or Europe.

If the EU is to build up resilience against future crises, its efforts now should be focused on gathering more data on supply chain risks and embedding deeper regulatory co-operation with key countries. Only in specific instances should it consider providing financial incentives for companies to diversify production and sourcing.

COVID-19 demonstrated that member-states, and the systems they rely on, were unable to respond to a global pandemic. There have been notable problems obtaining ventilators from China and paracetamol from India. Countries have even had to contend with being outbid for personal protective equipment (PPE) by the US. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Global Trade Alert, a group that monitors global protectionism, estimates that across 86 jurisdictions, 157 export controls on medical supplies and medicines have been implemented.

The EU is already one of the biggest global producers of medical products, and the biggest exporter.

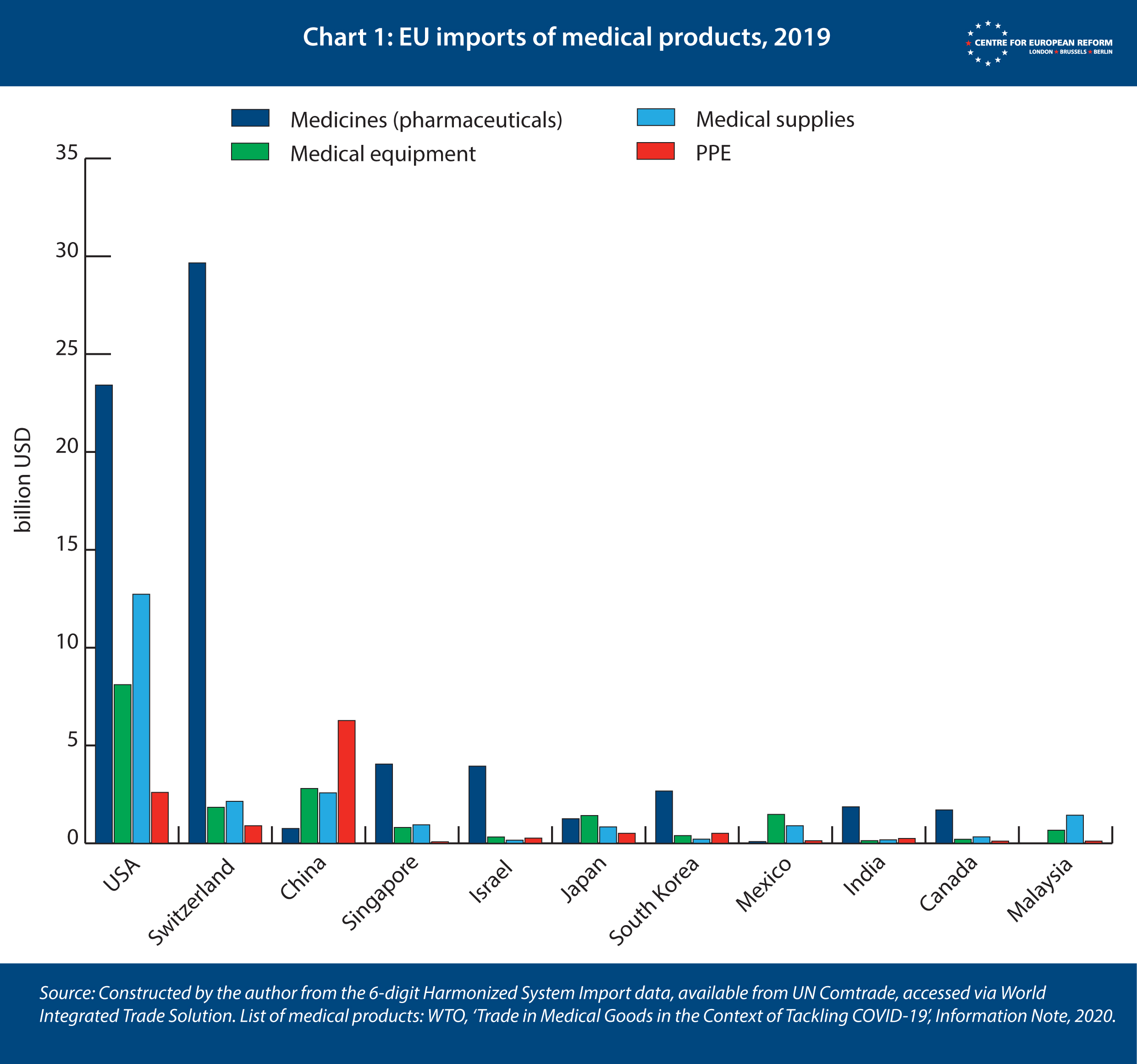

But how big is the problem for Europe? The EU is already one of the biggest global producers of medical products, and the biggest exporter. When it comes to imported medical products, particularly pharmaceuticals, it sources the vast majority not from Asia, but from the US ($47 billion) and Switzerland ($35 billion). However, it does import the majority of its PPE from China (Chart 1).

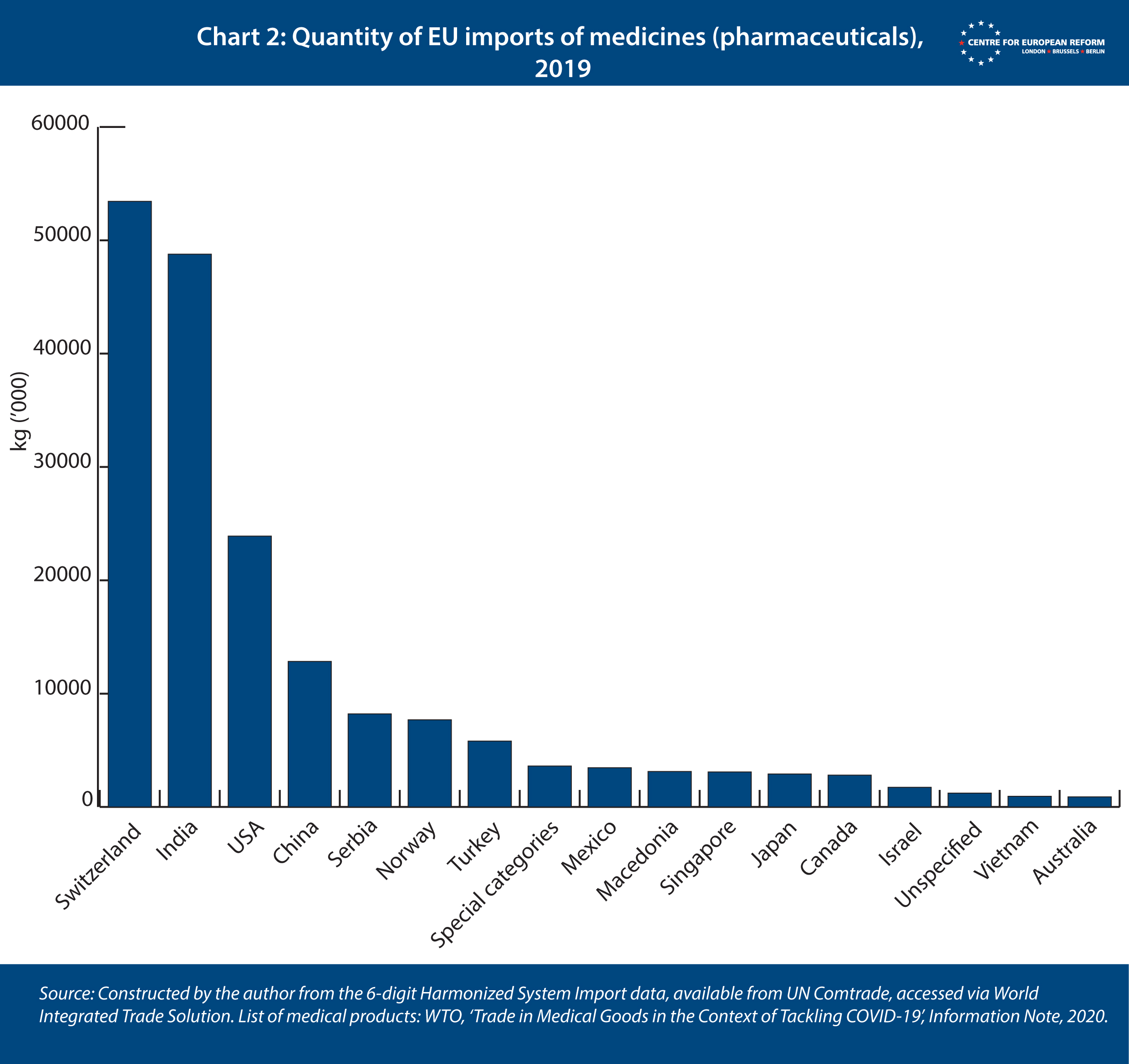

Yet a focus on the value of imports can be misleading. While the US and Switzerland tend to produce expensive and innovative drugs, cheaper generic medicines and active ingredients imported from elsewhere are also important. When accounting for the quantity of pharmaceuticals imported by the EU, rather than their value, India shifts from being the EU’s sixth biggest provider to second (Chart 2).

The trade-off the EU is facing is that if it does onshore the production of generics, active ingredients and PPE, in order to reduce its reliance on India and China, higher wage costs will lead to these products becoming noticeably more expensive. From a purely financial point of view, it remains sensible to produce low innovation medicinal products in countries with relatively low labour costs. But as the COVID-19 crisis has shown, Europe risks being left exposed when production of certain essential medical products is overly concentrated in one place.

Before it decides what action to take to avoid future problems, the EU must first establish exactly where the vulnerabilities in medical supply chains lie. To do so, it must work closely with producers to ensure any response is based on accurate data. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has already begun this process, by monitoring shortages of pharmaceuticals, but coverage needs to be expanded to include other medical products. The EMA may need more funding for the task.

Where tariffs have recently been removed to facilitate the import of vital medical products, they should not be reinstated. Trade economists Simon Evenett and Alan Winters propose a multilateral bargain whereby tariffs are not reinstated and in exchange exporter countries make binding commitments not to implement export curbs in a crisis. This is a sensible approach. As such, the EU should support the trade initiative launched by New Zealand and Singapore to ensure the free flow of essential goods, which commits to the removal of tariffs and the avoidance of export curbs on 120 medical products.

The EU’s main priority should be increasing regulatory co-operation with its trade partners, so that products imported during an emergency meet EU safety standards.

However, tariffs are not the biggest issue: they are zero-rated for most medical products anyway. The EU’s main priority should be increasing regulatory co-operation with its trade partners, so that products imported during an emergency meet EU safety standards. Many Chinese-made ventilators and masks failed to do so. The EU should build on existing engagement with Chinese and Indian regulators, with the ultimate prize being a mutual recognition agreement covering good manufacturing practice for pharmaceuticals and medical products.

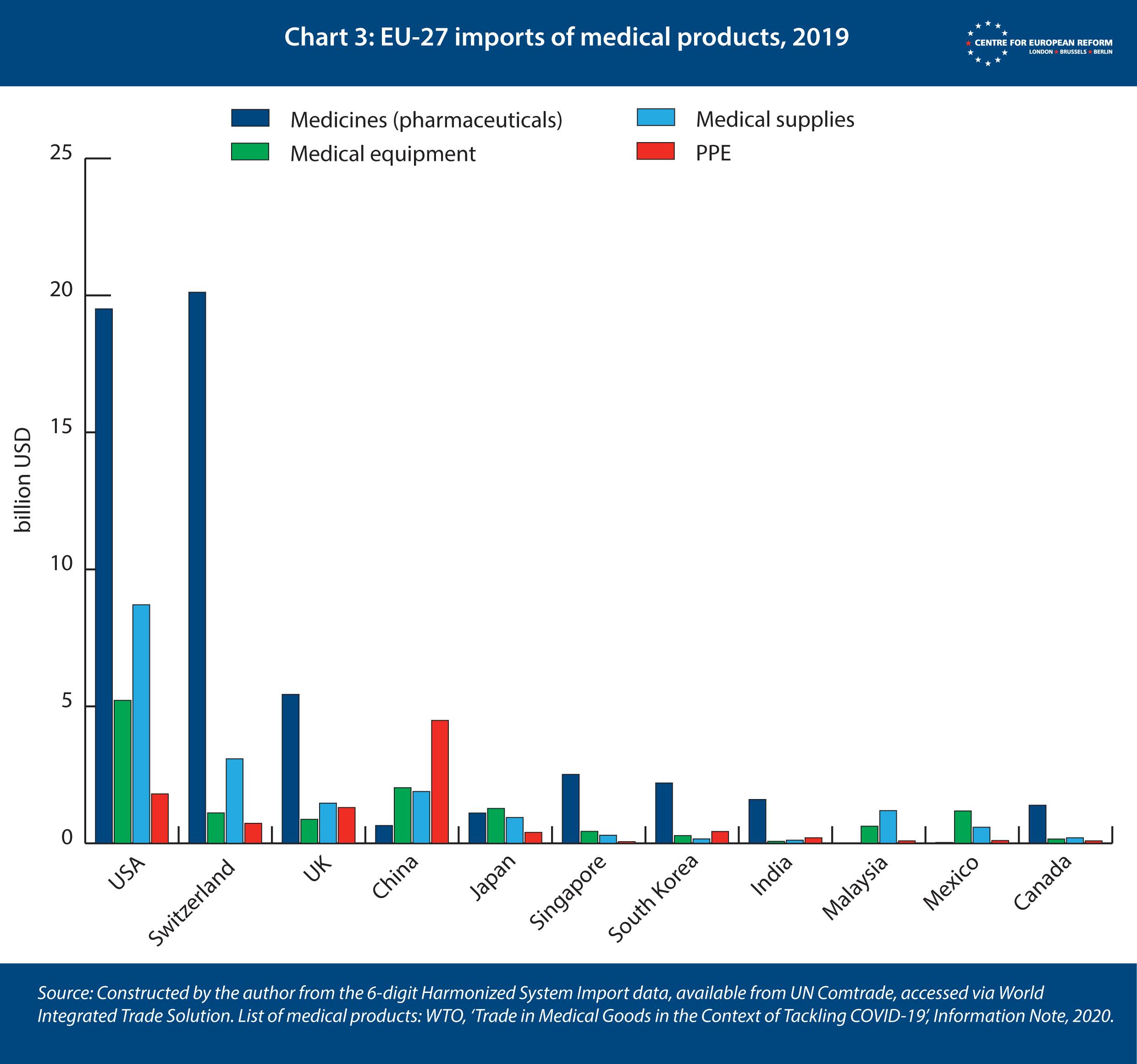

After Brexit, the EU cannot ignore the UK’s role in its medical supply chains. After the current transition period, Britain will compete with China to be the third-biggest supplier of medical products to the EU (Chart 3), even if new trade frictions between the EU and UK reduce trade to some degree. It is in the EU’s interest to engage with the UK’s request for a free trade agreement that would include enhanced provisions allowing for mutual recognition of good manufacturing practice in pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, batch certification, good clinical practice and information-sharing arrangements.

To avoid being caught empty-handed in future, the EU should expand its recently established stockpile of medical equipment. The European Commission should be responsible for releasing supplies to the countries with most need. That would reduce the incentive for member-states to put in place restrictions on exports of medical products to each other, as happened when the coronavirus initially reached Europe.

An EU-wide stockpile will also create an opportunity for targeted intervention. Diversifying supply chains is expensive for companies, and the cost of reconfiguring them will either fall on consumers or governments. Japan has set aside $2 billion of its COVID-19 stimulus package to help its companies move the production of vital products out of China and into Japan and the wider ASEAN region, but the response from business has been muted. An alternative approach could see the EU only buy medical products for its stockpile from companies that are able to demonstrate that their supply chain is resilient to a variety of shocks, including by not being overly exposed to one country or region. The EU should be prepared to pay a premium for sucha service.

Ultimately, when considering how to strengthen medical supply chains, the EU needs to be acutely aware of the role it wants to play in the world. It cannot hold itself up as an advocate of openness and multilateral co-operation if it chooses to look inwards and rely on its own resources in a crisis. Pursuing self-sufficiency through the forced onshoring of medical supply chains is not a solution to the problems identified by the current pandemic, but there is still much that can and must be done to ensure Europe does not get caught out again in the future.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.