Navigating accidental illegality

Next year many companies selling goods or services between the UK and EU will inadvertently break some rule or other. But the immediate consequences of their inevitable infractions remain uncertain.

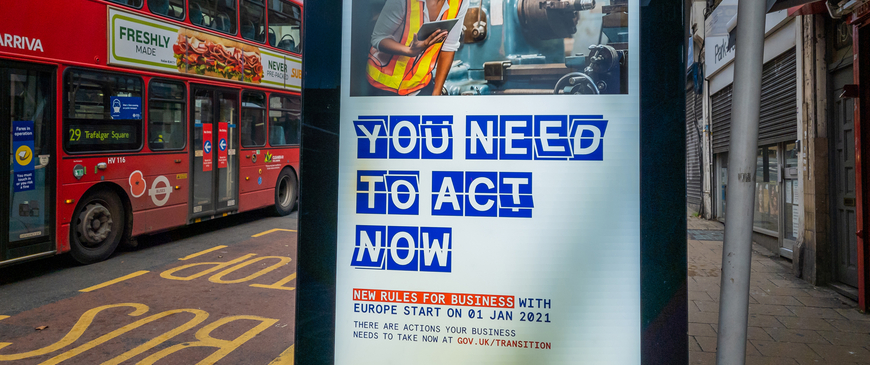

Even if the EU and UK succeed in concluding a free trade agreement (which at the time of writing is uncertain), on January 1st 2021 hundreds, perhaps thousands, of companies selling goods or services between the UK and EU will be breaking some rule or other, if only by mistake. Packets will be mislabelled, financial products will be sold from the wrong jurisdiction and people travelling to countries to meet clients will breach the terms of their visa. This accidental illegality will be widespread, and is an inevitable consequence of asking businesses to adjust to a radically different operating environment at breakneck speed.

On January 1st 2021 hundreds, perhaps thousands, of companies selling goods or services between the UK and EU will be breaking some rule or other, if only by mistake.

It is not a question of whether companies will break the law – they will – but how vigorously the EU and UK authorities choose to enforce the new rules. Companies evidently need to fall into line as quickly as possible, but will the approach taken by regulators and market surveillance authorities be heavy-handed or more accommodating? The sheer number of temporary derogations and day-one mitigation measures announced by the UK suggest that, at least to begin with, it will prioritise cross-border flows over strict enforcement of the rules. But despite some limited measures being announced by individual member-states – Belgium will not penalise companies that have made honest mistakes on their customs declarations for the first two months of the year, for example – there is still considerable uncertainty regarding the EU-wide approach.

Take product labelling. From January 1st, as is the case now, all British-produced products sold in the EU will need to have a CE mark applied, to show conformity with EU standards. What changes is that the producers in England, Wales and Scotland (Northern Ireland has its own specific issues) will not be able to directly release the product onto the European market. Instead, the EU-based importer will be required to accept liability if anything is found to be out of order. As such, the CE-marked product will have to be accompanied by a label listing the address of the EU importer/distributor (rather than the British producer’s). For EU-produced goods sold in Britain, the UK government has announced that it will recognise CE marking until at least the end of 2021, but from January the goods will need to be accompanied by the importer’s details.

There has been a lot of confusion on the issue of labelling, with the UK’s guidance changing over the course of the year. It should not therefore be surprising if many imported products are not accompanied by the correct documentation when placed on the EU or UK markets. Whether the correct labels have been applied to imported goods is not usually checked at the border, but in the marketplace by the relevant countries’ market surveillance authorities. Failure to comply can lead to product recalls, fines and (theoretically) imprisonment. In practice, we do not know what approach EU member-states and UK authorities will take to policing and ensuring compliance.

Legal uncertainty exists even for well-prepared UK-based investment banks that plan to continue selling their services to EU-based clients. In the expected absence of equivalence arrangements covering investment banking, UK-based firms that have established an EU entity are planning to rely on a process called reverse solicitation to justify continuing to serve existing EU-based clients from Britain. This is an area where individual member-states’ regulators have discretion, and the UK firms will need to be able to convincingly argue that it was entirely the client’s decision to continue to buy services from the UK-based operation, even though they were given the option to move their custom to an EU-based entity. Investment banks must set up an EU-based subsidiary, move EU-focused sales teams to within the EU and offer EU-based clients the opportunity to shift their business out of the UK before they can confidently accept custom through reverse solicitation. Even if the bank has taken all of these steps, and can make a convincing argument that it is acting entirely at the client’s direction and in the client’s interest, it still runs the risk of falling foul of the regulator – especially if a lot of trading activity remains in the UK. At best UK-based investment banks are looking for legal assurances that they will receive a warning from regulators before facing sanction.

Legal uncertainty exists even for well-prepared UK-based investment banks that plan to continue selling their services to EU-based clients.

This heightened degree of operating uncertainty increases the cost of doing business – once routine transactions will now need to be examined by lawyers, and risk assessments will need to be undertaken. At the more extreme end, some UK firms fear that the legality of long-term trades with EU-based counterparties (for example a bilateral derivatives contract) could be called into question, either by the counterparty if the trade goes against them, or by EU regulators. Here the issue is not that investment banks have failed to prepare for new post-Brexit terms of trade – they have spent a lot of money doing so – but that the regulatory and enforcement environment is uncertain and discretionary.

Even travelling for work becomes more tricky. While visas will not be required for UK nationals going on business trips to the EU from January 1st (so long as they do not stay for more than 90 days in a 180-day period), there will be restrictions on the type of activity they are permitted to carry out. Generally speaking, short-term business visitors will not be able to sell products or services to the general public or receive payment from a business or person based in the EU. Meetings and consultations might be permitted, while market research and commercial transactions might not be. However, there is no EU-wide list setting out which activities are permitted or not (although a future EU-UK free trade agreement could provide a partial one) and the types of permitted activities vary by member-state.

As with the examples above, the enforcement environment matters – and while it might seem inconceivable that British business people entering the EU will be interrogated at the border by jobsworth officials, it is possible. For EU nationals entering the UK for a business trip, breaching the terms of their visa could see their employer face civil penalties of up to £20,000 per non-compliant visitor, jail time and severe reputational damage. While a degree of leniency, at least in the short-run, might be expected, if there are continued breaches at some point authorities will probably take a harder line.

The three examples highlighted in this piece provide a snapshot of the issues facing companies in the New Year. Technically, while all of the above (and more) applies whether there is a EU-UK trade deal or not, for political reasons regulators will be more inclined to be indulgent if there is an agreement. But any grace periods are likely to be short, discretionary and inconsistently applied across member-states, if they exist at all. Beyond the headline grabbing queues at the border, businesses trading goods and services between the EU and UK face the unenviable task of navigating a confusing legal and enforcement environment for the foreseeable future.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.