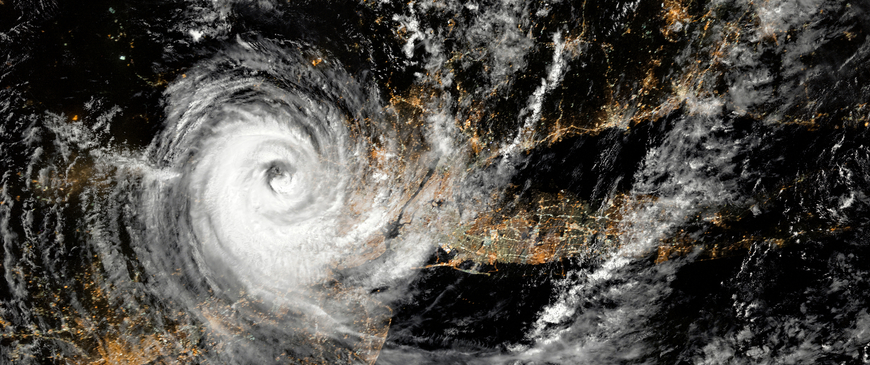

Trump and Europe: Atlantic hurricane season?

Trump's withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal adds further stress to the transatlantic relationship. European responses must avoid making things worse, for both sides' sake.

The Atlantic hurricane season does not officially start until June 1st, but US President Donald Trump’s decision on May 8th to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – the Iran nuclear deal – has triggered an early transatlantic storm.

In pulling out of the agreement – which froze Iran’s nuclear weapons programme, in exchange for sanctions relief – Trump ignored pleas from all his main European allies. Unless Trump changes course, sanctions will kick in later this year, hitting European firms that do business with Iran harder than they hit Iran itself. It appears unlikely that an EU plan to ban European companies from complying with US sanctions on Iran will stop firms doing the White House’s bidding, for fear of US punishment.

Unless #Trump changes course on #Iran #JCPOA sanctions, European firms that do business with Iran will be hit harder than Iran itself.

This is the latest move by Trump that puts the US at odds with its European allies. In June 2017 he withdrew the US from the Paris climate agreement; he has threatened to impose tariffs on European steel, aluminium and vehicle producers on spurious national security grounds; and he has regularly criticised NATO (even to the point of suggesting that the US might not defend an ally under attack if it had not spent enough on its own defence).

In response, European leaders are becoming more vocal in their criticism of Trump. British Prime Minister Theresa May, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel issued a joint statement on May 8th expressing “regret and concern” at his withdrawal from the JCPOA.

For many EU member-states, the reflex has been to look for purely European approaches to international challenges. In remarks on May 10th at a ceremony in Aachen to award this year’s Charlemagne prize for services to European unification to Macron, Merkel said that the US would no longer simply protect Europe; Europe had to take its fate into its own hands. Macron, in accepting the prize, said that Europe should not allow its trade policy to be decided by “those who blackmail us while explaining that the international rules that they contributed to drafting are no longer valid because they are no longer to their advantage”. He also warned against allowing even allies who had been “friends in the hardest times in our history” to take foreign and security policy decisions for Europe. And in a speech at the European University Institute on May 11th, Federica Mogherini, the EU High Representative for foreign and security policy, bemoaned the fact that “screaming, shouting, insulting and bullying [are] systematically destroying and dismantling everything that is already in place”. She argued that the world needed a change of attitude, from confrontation to co-operation, that only the EU could work for; this, she claimed, gave Europeans a huge opportunity.

There have been rows between the US and its European partners before, from Suez in 1956 to the Iraq war in 2003. Recognition of shared interests and values has always enabled the parties to patch up their quarrels. But commentators argue that this time it is different. An editorial in Germany’s Der Spiegel on May 11th claimed that “the West as we once knew it no longer exists”, and called for “clever resistance against America”. The American writer James Traub described the Atlantic alliance in a Foreign Policy article as “already a corpse”, and said that Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA had driven the last nail into its coffin.

An #EU plan to ban European firms from complying with US sanctions on #Iran won’t work: firms fear US punishment more.

It must be tempting for European leaders to respond in kind to Trump’s provocations, but they should resist. Trump’s views on trade, the ‘unfairness’ of the EU and the shortcomings of allies have been consistent for many years, and are unlikely to shift dramatically. Nevertheless, European leaders should continue to try to nudge him in more constructive directions where they can, as diplomatically as possible. They should also do more to engage with US priorities outside Europe, where US and European interests converge, particularly in Asia.

Rather than suggesting that disagreements with Trump offer Europe an opportunity to go it alone, European leaders should try to strengthen public support for transatlantic ties. As well as underlining the value of the security partnership with America, they should emphasise the importance of bilateral trade and investment to Europe’s prosperity, despite the failure (so far) to negotiate a transatlantic free trade agreement. It will not be easy to overcome growing public antipathy towards Trump (especially in Western Europe), but it is essential to minimise the damage to broader transatlantic relations.

One lesson that Europeans should learn from the election of Trump is that it is no longer just coastal elites whose views matter in the formation of US foreign, defence and trade policy. EU and European states’ public diplomacy efforts need to be directed at a wider audience. And where they can, European countries should be ready to work with members of Congress, and with US states or cities – as they have on climate change, for example.

For many #EU member-states, the reflex response to #Trump‘s foreign policy has been to look for purely European approaches to international challenges.

American perceptions of their European allies would improve if Europe invested more in its own defence and security. The German government’s new budget proposal foresees defence spending falling to 1.23 per cent in 2022, rather than rising towards the NATO target of 2 per cent by 2024 – exactly the wrong signal to send. But effective defence today demands more than just tanks, ships and aircraft – it needs resilient societies. Russia has shown in recent years that it can easily exploit the divisions in Western countries where a significant part of the population feels alienated from the establishment running the country, or distrusts state institutions.

The EU and US should both do more to increase transatlantic contacts between young people – at present there are almost four times as many Chinese students as Europeans in the US, and more than five times as many Chinese students as Americans in Europe. China is an important partner for both the US and Europe; but for the long-term viability of the transatlantic relationship Europeans and Americans have to get to know each other better. The days when hundreds of thousands of US troops were in Europe with their families, exposing Europeans to the American way of life and learning something about their hosts in return, are over.

Even if Trump turns out to be a one-off, and America reverts to the mean after him, neither Europe nor the US should take the survival of the transatlantic partnership for granted. But for the foreseeable future, the two sides of the Atlantic will still have more interests and values that unite them than that divide them. There is no more sense in a ‘Europe first’ policy than in Trump’s ‘America first’ approach. The right response for Europe in the face of the current administration’s unilateralism is to work with transatlanticists in the US to preserve as much as possible of the partnership, so that once Hurricane Donald has blown over – whether that is in 2021 or 2025 – there are still strong foundations on which to rebuild.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy of Centre for European Reform