Has the last trump sounded for the transatlantic partnership?

- Donald Trump’s inauguration felt like the end of the post-World War Two era to many people. Trump disavowed 70 years of US international engagement in favour of ‘America first’. But Europeans should understand that Trump is not to blame for all the threats to the transatlantic partnership; longer term changes in the relationship are also at work.

- The US and EU are still each other’s most important trading partners, though China is catching up, both in the American and the European markets. The US and EU have the largest stocks of investment in each other’s economies; China lags far behind.

- Though not all of Trump’s predecessors were convinced supporters of globalisation, he stands out for his hostility to multilateral free trade and the institutions that underpin it. Europeans should be prepared to make common cause with other US trading partners to resist Trump’s more protectionist acts.

- NATO remains the bedrock of the transatlantic partnership. But the bonds are looser than they once were. Trump regularly implies that the US might not defend allies who do not meet NATO’s spending target. Even so, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US has begun to invest more in the defence of Europe.

- Trump and those around him do not understand the EU. For Trump, it is another means by which the US’s trade partners cheat it. For some in his administration, it is an obstacle to bilateral relations between the US and individual European countries. Differences of view between Trump and his team make it hard for the EU to navigate the US policy-making process.

- People-to-people links between the US and Europe are important but declining. Migration from Europe to the US has become much less significant over the last few decades; more recent immigrants have more ties to Asia and Latin America. Numbers of Chinese students in the US and EU far outstrip European students in the US or US students in Europe.

- Trump’s hostility to the EU and NATO is not so far reflected in US public opinion, except among his core supporters. Most Americans still have positive views of the EU, NATO and major European countries.

- Trump is having a much more serious effect on European views of the US; the proportion of Europeans with a positive view of the US has fallen dramatically since Barack Obama left office.

- Trump’s team has so far managed to reassure Europeans of the US’s continued commitment to the transatlantic partnership. But recent personnel changes in the White House and the State Department are likely to increase tensions. Iran is a probable flashpoint.

- Transatlantic disagreements are nothing new. But some of the shared assumptions about the importance of the relationship which acted as shock-absorbers in the past may now be weaker. The breakdown of the transatlantic partnership would be damaging to both the US and Europe.

- Europeans should keep trying to influence Trump’s views, however hard it might be to change his negative opinion of US allies. Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel were right to visit Washington, and Theresa May is right to invite Trump to London. But European leaders should also work on strengthening public and Congressional support for the transatlantic partnership.

- European governments also need to put more effort into persuading European public opinion that opposition to Trump’s policies can be combined with support for transatlantic ties. On both sides of the Atlantic more needs to be done to increase the ability of societies to resist narratives designed to drive wedges between Europe and the US.

- The underlying interests of Western democracies have not changed because Trump is in office. His approach to Europe should be a wake-up call, not a sign that the world as we know it is ending.

The inauguration of Donald Trump as US president in January 2017 felt like the end of an era to many people on both sides of the Atlantic. That era had begun in 1945 with the end of World War Two. America did not then retreat from the world, as it had done after World War One. Instead, it stayed to build institutions to buttress peace and prosperity (and often, though not always, democracy) in Europe and beyond. Not all post-war US presidents were convinced internationalists, but all believed in the importance of this network of institutions in protecting America’s interests.

In his inaugural address, however, Trump explicitly disavowed America’s international engagement, claiming that it had benefited foreign countries at the expense of the US. In his perception of the world, the US had enriched foreign industry and ruined its own; subsidised foreign militaries while “depleting” its own; defended others’ borders and neglected America’s; and redistributed the wealth of the American middle class across the world. Trump proclaimed: “From this moment on, it’s going to be America First”.

Europeans are right to worry about what Trump’s policies will mean for the transatlantic relationship. But they would be wrong to blame him for all its problems. Europe has sometimes taken America’s leadership role in the world for granted. With the contrasting visits to Washington of French President Emmanuel Macron (regarded as a contributor to international security, and greeted warmly) and German Chancellor Angela Merkel (subjected to lectures on the EU’s excessive trade surplus and Europe’s inadequate defence spending), Trump showed, in his idiosyncratic way, that he expects Europeans to do more for themselves.

This policy brief looks at the changing trends in US relations with Europe, including patterns of trade and investment, military engagement, EU-US relations, people-to-people contacts and US and European attitudes to each other. It examines whether America’s allies (and adversaries) can afford to ignore what Trump says and focus on what his officials do. And it suggests steps that Europeans and internationalist US leaders can take to ensure that the transatlantic relationship survives, even if Trump means what he says and acts on it.

Trade and investment

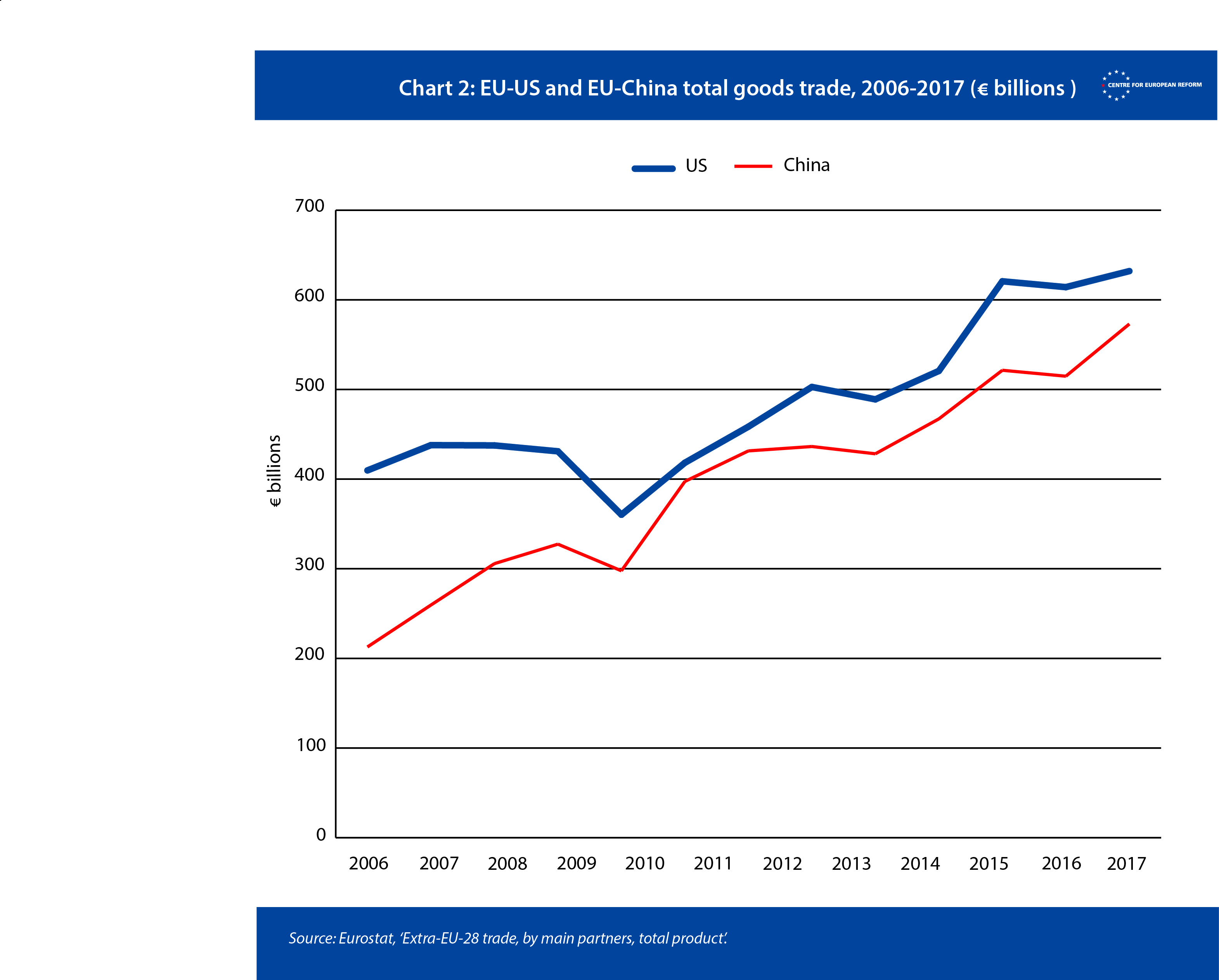

The US is consistently the EU’s largest trading partner and vice versa. But US figures show that China’s total trade with the US (in terms of exports and imports of goods) is steadily catching up with that of the EU (see Chart 1). Meanwhile, US trade in services with China (including Hong Kong) has also risen rapidly, almost doubling from 2010 to 2016, though they still lag far behind US-EU trade in services ($89 billion to $407 billion).1

In the case of the EU, the gap in the value of trade with the US on the one hand and China on the other has remained relatively stable since the financial crisis of 2008-09 (see Chart 2). As a percentage of the EU-28’s total external trade, however, China’s share has risen from 5.5 per cent in 2006 to 10.5 per cent in 2017; meanwhile, the US share has declined from 23.2 per cent to 20 per cent. China already exports more to the US than the EU does, and more to the EU than the US does. Trade in services between the EU and China (including Hong Kong) has also grown, by 55 per cent from 2010 to 2016.

he EU and US also have the largest stocks of investment in each other’s economies: just over €4.5 trillion US investment in Europe, and just over €3 trillion EU investment in the US as of 2016.2 By comparison, Chinese investment stocks in Europe are relatively trivial, at a little over €35 billion (according to Eurostat) or possibly €58 billion (according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce) as of 2015,3 while the EU’s investments in China amounted to slightly less than €190 billion. But EU countries invested more in China than in the US in three out of four years from 2013-16, according to Eurostat; China’s importance to its partners is growing.

Trump’s belief that trade deficits represent theft from America by its trade partners is damaging the transatlantic relationship.

Tweet thisBluesky thisIn Trump’s first year in office it was possible to make the case that his actions on trade were less radical than his rhetoric, and that his focus might be on forcing concessions from China rather than the EU. Though his administration included trade hardliners, he also had more mainstream, pro-trade Republicans. Those looking for reassurance could remind themselves that even though Obama ultimately launched talks on a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and was responsible for concluding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP – a 12-nation free trade agreement), he was not initially an enthusiastic free-trader. Indeed, the Democratic Party has long been suspicious of free trade, which it sees as threatening the jobs of American workers by allowing US firms to export jobs to countries with lower employment and environmental standards. To get his party on board for the TPP negotiations, Obama had to stress that the pact would oblige US trade partners to raise their standards. The Democratic candidate in the 2016 US Presidential election, Hillary Clinton, also opposed TPP during the campaign.

Trump’s direction of travel has become progressively more worrying, however. His first act was to withdraw from the TPP (though he has also hinted that he might try to negotiate re-entry).4 He launched an attempt to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada and Mexico. He has attacked the EU, claiming that its trade policies have been “brutal” to the US (though he has not (yet) imposed tariffs on German cars or other goods, despite threatening to do so). He has imposed significant tariffs on a long list of Chinese goods, ranging from pharmaceuticals to high-technology electronic equipment.

Much more worrying than any measures aimed at getting concessions from specific countries were the tariffs he imposed on steel and aluminium exports from a number of countries including China. Even though Trump has temporarily suspended the tariffs for most of the US’s allies, including the EU, in claiming that such imports undermined US national security he has threatened much wider damage to the rules-based system. He is exploiting a legitimate WTO right to break the rules for national security reasons, designed essentially for use in wartime, and is using it for purely protectionist purposes.

At the same time, at various points in the last year Trump has suggested that he might link Chinese help in ending North Korea’s nuclear programme to reducing pressure on China over trade issues. In so doing, Trump has underlined to Beijing that good political relations are now more important than objective market conditions in determining tariffs – exactly the wrong message to send, at a time when the EU and US should both be trying to persuade China to play by the rules of the WTO. Trump’s actions are consistent with his hostility to the WTO: he has threatened to withdraw from it; and he has tried to paralyse its Appellate Body by blocking the appointment of new judges.5 The Appellate Body hears appeals against the findings of investigations in trade disputes, and is vital to the running of the WTO.

Trump’s rejection of the tenets of free trade and his belief that trade deficits represent theft from America by its trade partners are damaging the transatlantic relationship. One of the purposes of TPP and TTIP was to enable the US and its allies to set global trade rules for the foreseeable future, offering China (at some unspecified point in the future) a chance to join in these large regional trade arrangements, but only on the terms set by their existing members. The demise of TTIP means that China is now in a much better position to bargain with the EU. Indeed, it might also be in the EU’s interest to work with China to mitigate the damage to the international trading system from which both have benefited economically.

The transatlantic defence partnership

Since the Second World War, defence has been an essential element of the transatlantic relationship. Trump complains that Europe is not pulling its weight; but in reality both European forces and US forces in Europe have shrunk significantly since the end of the Cold War (though both are increasing again now). High US defence spending is no longer driven only by confrontation in Europe, but by worries about a rising China, and by continued counter-insurgency operations in Afghanistan and the Middle East – concerns which for the most part Europeans do not share.

In the last years of the Cold War, NATO’s 13 European members (excluding Iceland, which has no defence forces) had around 3.5 million service personnel, and were responsible for around 40 per cent of allied defence expenditure. The US had around 2.2 million service personnel, of whom 315,000 were deployed in Europe.6 The US was responsible for a little less than 60 per cent of NATO members’ defence spending.

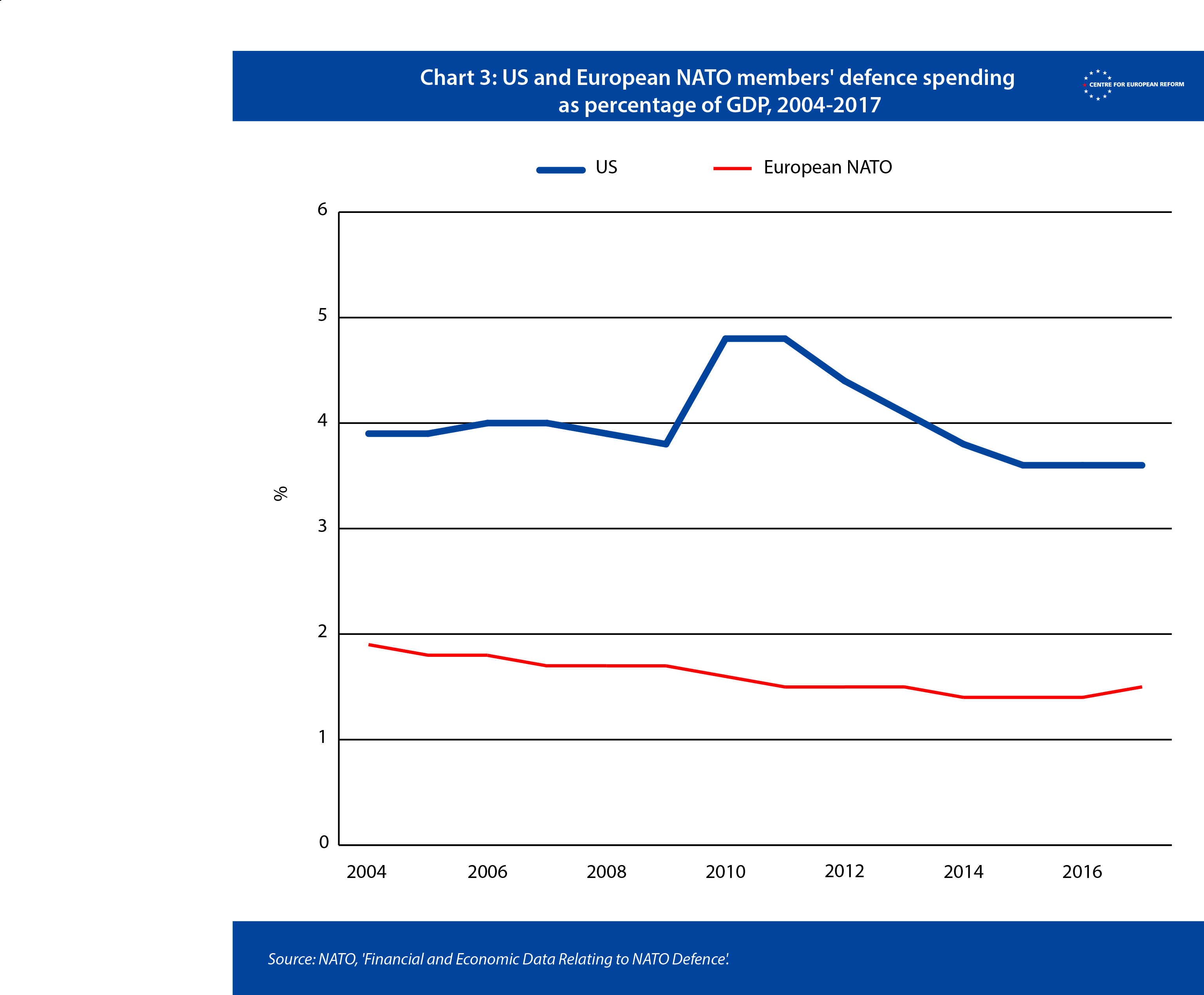

By 2010, however, the US defence budget made up over 70 per cent of the NATO total; NATO’s 26 European members contributed only 27 per cent. Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine led to a slight recovery in European defence spending: in 2017, NATO’s European members accounted for 30 per cent of defence spending, while the US share had fallen slightly, to just over 67 per cent.7 But NATO’s European members only spent an average of 1.46 per cent of GDP on defence; the US spent 3.57 per cent (Chart 3).

In terms of personnel strength, in 2016 the 26 European members of the enlarged NATO had just under 1.8 million service personnel (out of a population of 550 million), while the US had 1.3 million from a population of 320 million. At the same time, the geography of US deployment had changed dramatically since the Cold War: in 1989, there were three times as many US personnel in Europe as in East Asia, while in 2016 there were more US troops in Japan and South Korea than in the whole of Europe combined.8

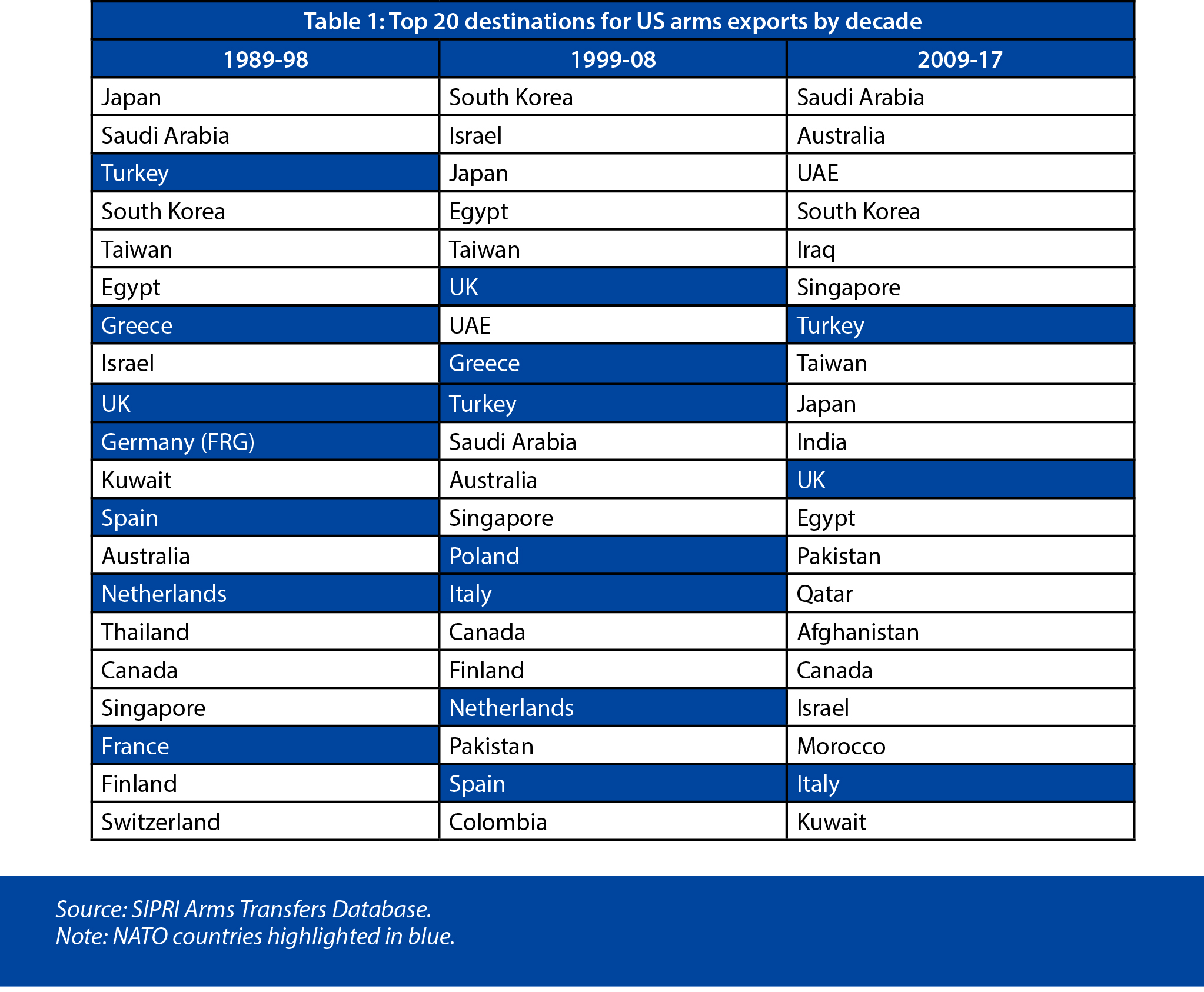

At the same time, even while the US was becoming the dominant arms supplier globally, NATO allies were procuring less from America. In the decade from 1989 to 1998, seven of America’s top 20 arms purchasers were NATO allies, with Turkey among the largest purchasers, in third place. In the decade from 1999 to 2008, there were still seven NATO allies in the top 20, but the highest placed was now the UK, in sixth. And in the nine years from 2009-17, there were only three NATO allies in the top 20, with Turkey highest placed, in seventh (see table 1). In the decade from 1989-99, around 30 per cent of US arms transfers were to NATO allies; in the nine years from 2008 to 2017, this fell to less than six per cent. This collapse reflected both a considerable increase in US arms transfers to countries in the Asia-Pacific region and the Middle East and a fall of almost two-thirds in sales to NATO countries.9

Arguments between the US and its allies over burden sharing are nothing new: US Senator Mike Mansfield began suggesting in the early 1960s that the US should withdraw troops from Europe and that Europeans should match their increasing economic prosperity with higher defence spending.10 For most of that time, even under presidents seen as friendly to Europe, there has also been a tension between the US desire for Europeans to do more for their own defence, and American hostility to European defence co-operation outside NATO.11 It was only in the last decade that the US became more supportive of EU defence efforts, driven by the urgency of getting Europeans to strengthen their defence capabilities, regardless of what institutional label they chose to put on their investment. Obama’s first defence secretary, Robert Gates, gave a warning to his NATO colleagues in farewell remarks in 2011: “If current trends in the decline of European defence capabilities are not halted and reversed, future US political leaders – those for whom the Cold War was not the formative experience that it was for me – may not consider the return on America’s investment in NATO worth the cost”.12

Trump’s attitude to NATO epitomises Gates’s fears. During his election campaign and subsequently, Trump criticised NATO member-states for “not paying their bills”. It is true that very few allies meet NATO’s target of spending 2 per cent of their GDP on defence. But the way Trump phrases his criticism of NATO implies that he thinks allies should pay the US for protection – which is not the way NATO operates. In March 2016 he complained that NATO was “unfair, economically, to us”. In July 2016 he complained that the US could not “be properly reimbursed for the tremendous cost of our military protecting other countries”.13 In December 2017 he claimed in a speech that he had told NATO leaders that they were “delinquent … and I guess I implied, you don’t pay, we’re out of there”. He went on to complain that a NATO ally could provoke war with Russia, and “we end up in World War Three for somebody that doesn’t even pay”. He also argued that NATO helped Europeans much more than the US, and that “the American people aren’t happy” with the alliance as it was.14

After meeting the presidents of the three Baltic States on April 3rd 2018 to celebrate the centenary of their independence, Trump again referred to NATO as “delinquent” and claimed that countries who had not been paying what they should, had paid “many, many billions” of additional dollars since he took office, though they would still have to pay more. And in a press conference with Merkel on April 27th 2018, Trump said that NATO was “wonderful, but it helps Europe more than it helps us”, complaining again that America was paying a disproportionate share of the costs of defending Europe.

Despite Trump’s bitter criticism of European defence efforts, the US’s practical commitment to the defence of Europe has grown.

Tweet thisBluesky thisBut Trump does not just want Europeans to spend more on defence. If the additional spending goes mostly to European defence companies, America’s allies will probably meet more hostility from Trump. He is not likely to react well to EU efforts to strengthen Europe’s defence industrial base if that reduces procurement from the US, even if the impact on European defence capability is positive.15 Trump will sympathise with the concerns of US defence manufacturers who fear being disadvantaged in the European market, and will believe that allies should in effect pay for America’s defence support by buying American weapons.

Despite Trump’s bitter criticism, however, the US’s practical commitment to the defence of Europe has grown over the last year. To some extent, this is simply a matter of building on existing policy. In 2014, Obama announced a ‘European Reassurance Initiative’ following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In 2016 the administration requested $3.4 billion for fiscal year 2017 (FY 2017, October 2016 to September 2017). This was designed to pay for more forces to deploy to Europe on rotation, more training and exercises in Europe, prepositioned US equipment in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands to allow rapid reinforcement from the US, and support to poorer NATO member-states and partner countries.

The amount requested for FY 2018 for the renamed ‘European Deterrence Initiative’ was increased to $4.8 billion, among other things to pay for prepositioning equipment in Poland, more rotational forces and more infrastructure to support deployments. And the Trump administration has proposed a budget of $6.5 billion for FY 2019, to modernise the equipment of US forces in Europe and preposition more tanks and other equipment. US forces now have a continuous presence in Poland (though the units involved rotate in and out every few months). While it would be unwise for European governments to think that they can get away with continued underspending on defence, it also seems that as long as US public opinion sees Russia as a threat to American interests, the US government will continue to invest in Europe’s defence.

US co-operation with the EU

If the US-NATO relationship is better than it looks, the same cannot be said for EU-US relations. Obama came to see the EU as an organisation that the US would work with in pursuit of shared goals, including tackling global issues such as climate change. Trump, by contrast, is hostile to the EU: he claimed shortly before his inauguration that “the EU was formed, partially, to beat the United States on trade”, he associated with eurosceptic politicians like Nigel Farage, and he spoke favourably of Brexit and implied that the break-up of the EU might be a good thing.16

It seems clear that Trump does not understand the EU’s role in foreign and security policy co-operation and sees no need to consult it on foreign policy issues; he has taken unilateral steps that have surprised and sometimes appalled the EU, such as withdrawing from the Paris agreement on climate change. Trump’s new national security adviser, John Bolton, is also an opponent of the EU, preferring to deal with individual states. His hawkish view on Iran (among other things) is at odds with that of EU High Representative Federica Mogherini, who sees the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA – the nuclear deal with Iran) as one of the EU’s greatest achievements.

US-EU co-ordination on key foreign policy topics was close during the Obama era. But the current administration is often disorganised in its approach, making it hard for Europeans to know who to listen to. Trump’s line on Russia is generally soft; but the Defence Department, Treasury Department, State Department and intelligence agencies are much firmer. In December 2017, the State Department announced that the US would supply lethal weapons to Ukraine; in March 2018 Trump congratulated Vladimir Putin on his re-election as Russian president (even though his advisers briefed him not to) and said in a tweet that Russia could “help solve problems with Ukraine”; in April 2018 the US Treasury imposed sanctions on companies and individuals close to Putin.

Those sanctions were a model of how not to deal with foreign policy partners. Trump clearly did not want to impose them at all, but was under pressure to do something to show that he was not in Russia’s pocket. Congress had mandated the imposition of sanctions in an August 2017 law, as a way to tie Trump’s hands; European interests were a low priority for both them and the administration. When the Treasury sanctioned various Russian firms, they did so without consulting the EU, even though the measures would have more effect on European than American interests, and even though Trump had promised in his ‘signing statement’ (a document setting out the president’s interpretation of a law that he cannot or does not want to veto but has reservations about) that he would co-ordinate with allies in imposing sanctions.

Transatlantic discussions are marred by uncertainty about which US department or agency can speak for the administration.

Tweet thisBluesky thisThe EU and US are also at odds over Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Though Europe and America have not seen eye-to-eye over the Middle East Peace Process for many years, they have managed to find ways to work together; but Trump has thrown in his lot with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and opponents of the two-state solution. His unwillingness to listen to any other views on Jerusalem and the impact of his decision has damaged transatlantic trust.

Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger famously complained that if he wanted to call Europe he did not know whom to call; now it is the EU that is frustrated by the lack of a single US point of contact able to set out a consistent policy line. Regular transatlantic discussions still take place, but they are marred by uncertainty about which department or agency, if any, can speak for the whole administration.

The EU-US relationship will be seriously challenged by disagreements over Iran. Trump must decide by May 12th whether to continue to waive sanctions against Iran. He has said that he will reimpose them if Iran refuses to renegotiate the JCPOA. If Trump walks away from the agreement, he will be at odds not only with Iran, China and Russia, but with the EU and the member-states. Last minute efforts are going on to get Iran to agree to restrain its disruptive behaviour in the Middle East and to end its ballistic missile programme. In their back-to-back visits to Washington, Macron and Merkel sought to persuade Trump to preserve the JCPOA, while also suggesting that there should be more pressure on Iran on other issues of concern. It is not clear either that their efforts will be enough to placate Trump. There is a good chance that some EU member-states would not agree to impose sanctions on Iran simply for refusing to accept new restrictions (though it would be easier for the EU to reach consensus on reimposing if Iran resumed uranium enrichment).

People-to-people links

The transatlantic relationship is not just built on calculations of economic and defence advantage. Kinship and contact between populations have also played an important part. Europeans made up the bulk of immigrants to the US until the latter part of the 20th century. But the demographics of migration have changed dramatically in the last three decades: according to the US census in 2000, none of the top ten countries of birth for residents born outside the US was European. That still leaves something in the region of 5 million American residents who were born in Europe, but far more of the recent arrivals now have connections to Latin America or Asia.

In Europe, on the other hand, the number of migrants from predominantly Muslim countries has grown. In 2016, Muslims made up 4.9 per cent of the population of the European Economic Area plus Switzerland; one forecast suggests that by 2050 they might be between 7.4 per cent and 14 per cent of the population.17 Depending on the long-term impact of Trump’s efforts to reduce or eliminate Muslim migration into the US, the result might be a growing cultural divide between the US and Europe: more people in Europe with reasons to dislike the US, and fewer family connections to underpin economic and security ties.18

The decline in the number of US troops in Europe has already reduced some opportunities for personal contact between Europeans and Americans. In 1960 there were about 400,000 US personnel in Europe, accompanied by over 320,000 dependents. In 1990, there were still 350,000 US troops stationed in Europe.19 At the height of the Cold War there were more than 100 US bases (of various sizes) in Europe. In the 1950s they were among the largest employers in the American zone of West Germany.20

Once the Cold War ended, however, the number of troops (and their dependents) and bases fell sharply. By the end of 2016, there were 65,000 troops permanently based in Europe, with 34 main bases, half of which were slated to close. Other forces rotated through Europe, without families. Over the period from 1945 to 2013, when the last American tank left Europe, many millions of Americans spent extended periods in Europe, and many friendships were formed. Those numbers will fall significantly as a result of America’s shrinking military footprint in Europe, even if some US troops are now returning, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

Despite Trump’s attacks on NATO, in 2017 the proportion of Americans with a favourable view of the alliance rose.

Tweet thisBluesky thisIn the last 20 years, transatlantic educational exchanges have also become relatively less important on both sides of the Atlantic. In 2000, there were over 80,000 European students in the US, compared with 60,000 from China and 55,000 from India. By 2017, there were 93,000 European students, 186,000 Indians and 351,000 Chinese.21 In 2000, there were fewer than 20,000 Chinese students in EU member-states; by 2015, there were almost 145,000. Over the same period, the number of US students only rose from 22,500 to 26,000.22 Academic communities in both Europe and the US are increasingly preoccupied with strengthening relations with Asia in order to tap lucrative higher education markets there; the more nebulous question of maintaining the transatlantic relationship is a lower priority.

Transatlantic tourism and business travel still flourishes, helped by the fact that most EU visitors have visa-free access to the US. European visitors to the US (including those from Russia and the six former Soviet states of Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus) rose from 8.8 million in 1995 to 15.7 million in 2015, before falling away slightly in 2016 and 2017. There are no precisely comparable figures for travellers from the US, but there were approximately 8 million US visitors to Europe in 1995, and about 11.4 million in 2015.23 The question is whether the decline in visits to the US over the last two years will continue. Trump’s determination to reduce migration is likely to deter at least some Europeans from visiting what may become a less hospitable country.

Trump’s impact on popular attitudes

One might expect that Trump’s views of the transatlantic relationship (and other international issues) would be consonant with those of most American voters, either because he influenced their views or reflected their prejudices. Trump’s negative view of NATO has some echoes in the views of American voters, indeed, but it goes well beyond them. Opinion polling suggests that even before Trump came to power there were worryingly low levels of support in the US for NATO. From 2010 to 2016, between 49 and 54 per cent of Americans had a favourable view of NATO. That was well below the levels of support for it in many European countries at that time, including Germany (55 to 67 per cent), the Netherlands (72 per cent) and Poland (64 to 70 per cent).

Yet despite Trump’s attacks on NATO, in 2017 the proportion of Americans with a favourable view of the alliance rose to 62 per cent.24 A separate survey showed that 69 per cent of Americans thought that NATO was still essential to US security – though among core Trump supporters, the figure was only 54 per cent.25 And notwithstanding Trump’s implied threats not to defend allies who do not meet NATO spending targets, only 38 per cent of Americans thought that was the right course (though among Republicans the figure was 51 per cent, and 60 per cent for core Trump supporters).

Officials admit privately that intemperate tweets from Trump can distract attention from good day-to-day co-operation.

Tweet thisBluesky thisTrump’s criticism of Europeans is not (so far) having an effect on the American public’s views of individual allies: polling in February 2018 showed that 84 per cent had a favourable view of France and Germany, and 89 per cent had a favourable view of the UK.26 But the president’s frequently stated desire for good relations with Russian president Vladimir Putin seems to be having an effect on US Republicans’ judgement of whether Russia poses a serious threat to the US: while 63 per cent of Democrats think it does, only 38 per cent of Republicans agree.

Americans do not share Trump’s negative attitudes to the EU, or to international trade. According to the Chicago Council survey, almost two-thirds of Americans (though only half of core Trump supporters) trust the EU to deal responsibly with world problems, and think the EU trades fairly with the US. Indeed, overall support for international trade has risen in 2017, with 72 per cent believing it is good for the US economy (compared with 59 per cent in 2016).

More problematic than his effect on US public opinion, however, is the impact that Trump is having on European views of the US. European approval of US leadership has slumped. Over the eight years that Obama was in office, an average of 43 per cent of Europeans had a favourable view of US leadership, while 28.5 per cent had an unfavourable view. At the end of Trump’s first year in office, 25 per cent had a favourable view and 56 per cent an unfavourable one. These figures are comparable with the last year of George W Bush’s presidency (19 per cent favourable and 53 per cent unfavourable).27 Among NATO allies, only in Albania and Poland did majorities take a favourable view of US leadership; and only in Montenegro, Poland and Slovakia was support for Trump’s leadership higher than for Obama’s.

‘The adults in the room’

Though the public perception of America has become much more negative in Europe in the last year, European governments have been somewhat reassured by their contacts with Trump’s senior advisers. When Trump was slow to reaffirm the US’s commitment to defend its allies under Article 5 of the NATO treaty, then National Security Adviser H R McMaster told the media that the president’s support for Article 5 was “implicit” in his remarks at the NATO Summit in May 2017. Vice President Mike Pence subsequently went to Tallinn and assured the Baltic States that the US stood firmly behind its treaty obligations. Rex Tillerson, then Secretary of State, stressed in December 2017 that the US also backed the EU, telling NATO ministers in Brussels: “The partnership between America and the European Union ... is based upon shared values, shared objectives for security and prosperity on both sides of the Atlantic and we remain committed to that.” Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said after a NATO defence ministers’ meeting in February 2018 that NATO remained the US’s “number one alliance”. The new US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, visited NATO within hours of taking office, and described US commitment to collective defence under Article 5 as “ironclad”.

Comments like these, and the firm backing from the US administration for the UK in its response to the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal, help to limit the damage to the transatlantic relationship. But in private, officials on both sides acknowledge that intemperate comments or tweets from Trump can undo the good work that his subordinates do, and distract attention from continued good day-to-day co-operation on many issues.

Worryingly for Europeans, a number of those around Trump that they felt most comfortable with have been fired or have resigned in recent months. Gary Cohn, director of the National Economic Council, seen as a supporter of free trade and an opponent of punitive tariffs, resigned after losing out to proponents of economic nationalism and protectionism. Trump dismissed two of the ‘adults in the room’, McMaster and Tillerson. Their replacements, John Bolton and Pompeo respectively, are less likely to act as restraints on the president. When Bolton was US ambassador to the United Nations under George W Bush, he was notoriously hostile to the EU and had poor relations even with the UK, normally the US’s closest ally in the UN Security Council. It may now be more difficult for Mattis and Pence to keep smoothing things over.

Can Europe and the US avoid drifting apart?

Physically, the Atlantic Ocean is getting wider by about 20 cm a year. Politically, Europe and America risk splitting apart much more quickly. The question is whether this is an inevitable result of diverging long-term interests, or the temporary product either of cyclical processes (anti-Americanism in Europe and isolationism in the US have waxed and waned over the last century) or of the peculiarities of the Trump administration.

Even if Trump only serves one term, it may be hard for the next generation of leaders to repair the damage.

Tweet thisBluesky thisA recent Chatham House report concluded that most of the factors influencing divergence between the US and Europe, such as military capabilities, political polarisation and leadership personalities, were cyclical; only a few (changing demographics; differing levels of dependence on imported food and energy resources; and differing attitudes to international institutions) were structural.28 The report did not encourage complacency, but it suggested that the structural changes would unfold over a long period, giving European and American leaders time to respond with policy corrections; and that some cyclical changes could be dealt with if Europe showed that it was investing more in defence and contributing more to common security. There is a risk, however, that the cyclical factors reinforce the structural factors in a way that has not happened before, doing more lasting damage to the transatlantic relationship.

Ronald Reagan was regarded in Europe as a dangerous warmonger when he took office in 1981; but he was strongly committed to European security. The US Secretary of State for six and a half of Reagan’s eight year tenure was George Shultz, an outstanding statesman who helped to lay the foundations for the end of the Cold War. Neither man called into question the institutional foundations of Western power. George W Bush was also a focus of European anti-Americanism, and there were some in his administration (such as Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld) who returned the favour, particularly when France, Germany and other European countries refused to support the invasion of Iraq in 2003. But Bush also had subordinates able to rebuild bridges, including Colin Powell (Secretary of State in his first term), Condoleezza Rice (National Security Adviser in his first term, then Secretary of State), Stephen Hadley (National Security Adviser in Bush’s second term) and Robert Gates (Secretary of Defense from 2006, retained by Obama till 2011).

In relation to trade also, though US administrations often imposed tariffs or quotas on European countries (and even more on the US’s Asian allies) when they believed that American companies were the victims of unfair competition, they did not seek to undermine the basic institutions of international trade. And they negotiated (or tried to) far-reaching trade agreements such as NAFTA (with Canada and Mexico), TPP and TTIP.

As a result, there were important shock-absorbers to get through rough patches in the transatlantic relationship. Those shock-absorbers may no longer be so effective; and Trump seems to be actively trying to destroy some of them. There are fewer Americans who feel a personal or a family tie to Europe, and fewer Europeans with close relatives in the US; fewer Americans have the experience of serving on NATO’s front lines as part of a common defence effort in Europe; unilateral US action on tariffs is putting relations with the EU under strain; and a significant number of Republicans agree with Trump’s implicit view that America would be stronger without international institutions to hamper it.

The result may be that even if Trump only serves one term in office, it may be hard for the next generation of US and European leaders to repair the damage, particularly in the context of structural changes tending to push them apart. That would be bad news, with effects beyond Europe and the US. Liberal democracies are far from perfect in their actions, either at home or abroad. But over time they have delivered better outcomes for more people than the alternatives. Since 1945, Europe and the US have worked together to spread democracy and free market ideas to more countries, particularly after the collapse of communism in Central Europe and the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. But in recent years, even before Trump came to power, liberal democracy has been in retreat. Freedom House, an international NGO which monitors the state of democracy, freedom and human rights worldwide, assessed that 2017 marked the twelfth consecutive year in which global freedom had declined. Political rights and civil liberties deteriorated in 71 countries, and improved in only 35.29

If the US stops trying to lead the free world, and becomes a more unilateralist power, at odds with not only its adversaries but its allies, Europe will be left as the main defender of the rules-based international order. Despite its economic weight, it is not equipped to take on that role. The EU does not have (and may never get) the unity of purpose and the political instruments to convert its economic weight into global influence. After Brexit, one of the most Atlanticist countries in Europe, and also one of the few with a global foreign policy, will be outside the EU, with reduced ability to influence the Union’s direction. Within the EU there will remain some leaders, such as Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, more inclined to reach accommodations with authoritarian powers such as China or Russia than to try to resist them. The next few years may decide whether ‘the West’ remains a pole of attraction for other countries, or whether it breaks apart, with some of its members drifting into the orbit of other powers.

Recommendations

Those on both sides of the Atlantic who still see the value of the partnership should take a number of steps to ensure that it can continue, in the face of both cyclical and structural pressures.

European leaders should continue to try to nudge Trump in more constructive directions, by flattery if need be.

Tweet thisBluesky thisDon’t give up on Trump. Trump’s views on trade, the ‘unfairness’ of the EU and the shortcomings of allies have been consistent for many years, and are unlikely to shift dramatically, but European leaders should continue to try to nudge him in more constructive directions where they can, with flattery if need be. During Macron’s state visit to Washington on April 23rd to 25th the French president seemed to be trying to balance a warm personal touch with delivering unpopular messages on areas of disagreement. Neither Macron nor Merkel has so far succeeded in getting Trump to say that he will not apply tariffs to aluminium and steel imports from allied countries. But they are right to keep trying to get him to change his mind about elements of his policy, even if they cannot influence the overall thrust.

British Prime Minister Theresa May was criticised for rushing to Washington after Trump’s inauguration, and for seeming to tilt the balance of her messages too far towards flattery and away from frankness. She is right to invite Trump to London in July 2018, however: Brexit or no Brexit, the UK, like other European powers, needs the US to stay engaged. Indeed, May will have the chance to stress to Trump that it is no more in the US’s interest to see the EU weak than it is in the UK’s: future European security will increasingly depend on an effective NATO and an effective EU co-operating to deal with threats that no longer fit neatly into the scope of either institution.

Senior EU officials like European Council President Donald Tusk and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker should not be afraid to pick up the telephone to Trump, Pence or other senior administration officials on the issues that matter to the EU – including to explain the damage that US industries would suffer in a transatlantic trade war. On burden sharing, Europeans should spend more on defence, but they could present their case better, including by stressing the importance of their non-military contributions to security such as some forms of development aid.

Europeans can also do more to engage with US priorities outside Europe, particularly in Asia. EU-US co-ordination on China policy is better than on many other regional issues but could still be better. There are regular contacts between the EEAS and the State Department. On trade, the two sides continue to work together on improving market access in China; but the US administration’s attitude to the WTO makes it hard for them to put co-ordinated pressure on China to open up. And China has already been able to use its economic influence to block EU consensus in the UN on criticising China’s human rights record; the EU should try to make it harder for Beijing to divide the EU, for example in the event of a regional security crisis over the South China Sea in which the US might seek European backing.

Work on strengthening public support for transatlantic ties. The long-term sustainability of the Western alliance will rely on continued popular support. It will not be easy to overcome ‘the Trump effect’ on public opinion in Europe (especially Western Europe – he is more popular in some Central European countries), but it is essential.

The more that Europeans think of America in a broader context than the latest tweet from Trump, the more likely they are to value the transatlantic relationship. The more they have contact with a broad range of Americans, not just the stereotypes often encountered in the media, the more likely they are to think of what they have in common, rather than what divides them. In responding to events in the US, European governments should use language carefully, making the distinction between US administrations (which may do things that they disapprove of), the American population (with as wide a range of views as any other population in a democratic society) and the transatlantic partnership (essential for the foreseeable future, regardless of ups and downs in relations with the various occupants of the White House). In the US, though favourable opinions of European countries have held up well in the face of Trump’s hostility, Europeans need to continue to stress to the American public that the transatlantic partnership is a long-term asset for the US.

Congress should increase funding for programmes to strengthen transatlantic solidarity, including the Fulbright programme.

Tweet thisBluesky thisMaintaining the transatlantic relationship should be a priority for public diplomacy funding. On the US side, activity to shore up European support for the partnership relies on Congress continuing to resist the administration’s attempts to cut the budget for cultural and educational exchanges. In 2017, the administration proposed a 55 per cent cut in the budget for FY 2018, from $634 million to $285 million; Congress rejected it. In 2018, the administration has proposed cutting the budget for FY 2019 even more brutally, to $159 million. The administration also wants to cut the budget of the National Endowment for Democracy (which supports a variety of programmes in Central and Eastern Europe to strengthen democracy and increase support for NATO) from $168 million to $67 million. Congress must now decide what to do; it should support and if possible increase funding for programmes to strengthen transatlantic solidarity, including the Fulbright programme, which currently pays for around 300 outstanding American students a year to study in Europe, and for Europeans to study in the US.

Do not leave the US to invest in transatlantic ties on its own. The European side must not behave as though maintaining transatlantic ties is a job for the US alone. In 2018, the British government is funding 42 Marshall Scholarships (for American university graduates to study in the UK). This is a 34 per cent increase since 2015, and the largest number since 2007.30 It is still a relatively tiny number. The EU’s Erasmus+ programme funded around 2,800 staff and student exchanges, in both directions, between the EU and the US between 2015 and 2017 – but students from developing countries are a higher priority for EU funding. Both the EU and individual member-states should design educational exchange programmes to bring Americans to Europe, whether for degree courses or shorter periods of study. A small, ring-fenced increase in the budget for the Erasmus+ programme in the next EU multi-annual financial framework could make a significant difference. European funding institutions should also ensure that the recipients of scholarships reflect the US’s changing demography. The 2018 cohort of Marshall Scholars were undergraduates in more than 20 states, with most US regions represented.

Look beyond capital cities and foreign policy elites. European countries and the EU should target public opinion in the US with collective as well as national messages, and they should not limit their targets to Washington and New York; the US should also reach out to the widest possible audience in Europe, especially those who are hostile to the current administration.

The larger EU and NATO member-states have consular posts in major US cities (France, Italy and the UK have nine each outside Washington; Germany has eight). In the past, their information efforts tended to be focused on national issues such as trade, investment and tourism promotion. The EU also has a delegation in Washington, which used to focus mostly on developing governmental and non-governmental networks ‘inside the Beltway’, rather than in the US more widely.

The EU delegation is now increasingly active elsewhere, directly and through the consulates of member-states and various Europe-friendly interest groups. Trump’s criticism of the EU, and his sometimes outlandish claims about social problems in European countries, have prompted more efforts by member-states and the EU delegation to make their case directly to business groups and others. The delegation arranges a few visits to Europe every year for mid-career professionals with the potential to reach senior positions. And half a dozen Commission and European External Action Service staff a year are on sabbatical at universities and think-tanks across the US, and able to act as informal ambassadors for the Union.

Eight US universities host Jean Monnet Centres of Excellence, funded by grants from the Commission, which organise events and provide information on the EU for students and the wider community. The Commission also funds eight Jean Monnet Chairs in the US (six at universities where there is no Jean Monnet Centre), supporting professors who specialise in EU studies. The Jean Monnet programme provides a useful if rather small network in the US, which could certainly be expanded.

Europe and the US have shown their vulnerability to ‘fake news’, which can be used to create divisions between them.

Tweet thisBluesky thisThere is no corresponding network for NATO, and there are legal constraints on what the US government could do (even if it wanted to) to encourage popular support for the alliance. But there is nothing to stop the embassies and consulates of NATO member-states working together on outreach, or arranging for ministers and senior officials to visit major cities across America, to talk to state-level politicians and civil society organisations.

It is even more important for US diplomats in Europe and visiting officials to speak to people outside the foreign and defence policy establishment. Diplomats cannot directly contradict the president’s attacks on the EU and NATO (though some have come close to it), but they can still emphasise the more positive comments of the vice president, defence secretary and others, and underline the continued value of Europe and the US working together to solve common problems.

Work with Congress to build up transatlantic links between legislatures. There are already a number of inter-parliamentary bodies in which European and American legislators meet. The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and its various committees bring together hundreds of parliamentarians in regular meetings to discuss topical issues (including burden-sharing). As part of the assembly’s work, the Parliamentary Transatlantic Forum organises an annual meeting in Washington with senior US administration officials for about 100 legislators from NATO and EU countries.

The European Parliament and the US Congress are involved in the Transatlantic Legislators’ Dialogue; MEPs and Senators and Representatives meet twice a year and hold teleconferences on issues of mutual interest. European Parliamentary committees and Congressional committees are sometimes in direct contact on legislation that may affect the other party. These EU and NATO contacts mostly go on under the radar, but could be given a higher public profile to emphasise that directly elected representatives look out for their constituents’ interests through the transatlantic links they develop. The President of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani, could play a more active role in building relations with senior congressional figures and explaining (for example) what is at stake for Europe in the Iranian nuclear deal.

Congressional delegations frequently visit Europe. More often than not, they visit a number of capital cities in quick succession. Their European counterparts should encourage them to meet ordinary citizens more often, and to travel outside capitals. Members of Congress can go further than diplomats in departing from the president’s stated negative views on the EU and NATO. They can accentuate the positive aspects of the relationship – including the importance of US investment in creating and supporting European jobs, and the extent of defence industrial collaboration.

Emphasise the importance of transatlantic trade and investment. Not only is the transatlantic economic relationship crucial to the prosperity of the US and the EU; when both sides agree, they can set standards that others will follow. Supporters of the international trading order hoped in the Obama period that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and TTIP collectively would enable like-minded countries to set labour, environmental and governance norms that other economic powers, above all China, would have little choice but to adopt. Trump’s withdrawal from TPP dashed those hopes.

TTIP was never popular in Europe, let alone with Trump. But business groups, European governments, parliamentarians and members of Congress and the European Commission need to do a better job of advocating for trade, on both sides of the Atlantic. They need to stress that if developed countries with high labour and environmental standards do not get the rest of the world to follow their lead, China and others will set lower standards for everyone.

Thanks largely to Trump, the world may stand on the brink of a trade war. The EU cannot allow Trump to steamroller it, or he is likely to keep coming back for more concessions. The EU needs to couple political messages in favour of transatlantic co-operation to open up China’s economy with willingness to respond in kind to Trump’s tariffs and other protectionist measures. And it should keep open the possibility of resuming negotiations on TTIP (perhaps under a new name) in future.

Strengthen transatlantic defences, in all forms. Defence is no longer (if it ever was) just a matter of how many ships, tanks and planes a country has. Europeans certainly need to spend more on conventional defence capabilities – both to reassure Americans, including Trump, that Europe is pulling its weight, and as a hedge against the risk that Trump or a future anti-globalist president may turn American public opinion against NATO, or refuse to honour the Article 5 commitment in a crisis. But both they and the US also need to work on other forms of resilience.

Both Europe and the US are vulnerable to state-sponsored or criminal cyber-attacks on critical national infrastructure and economic targets.31 They have also shown their vulnerability to ‘fake news’, conspiracy theories and propaganda, which can easily be used to create or increase divisions between them.

The ‘Media Literacy Index’ shows wide variations in the ability of European publics to identify and resist false narratives, with those in the Western Balkans particularly polarised and inclined to distrust each other.32 It is no coincidence that Russia has increased its anti-Western propaganda and intelligence efforts in the region, exploiting an identified weakness.33 Meanwhile, about 40 per cent of Americans believe wholly or partially in the conspiracy theory that the government has a secret programme using aeroplanes to put harmful chemicals into the air (the so-called ‘chemtrails’ conspiracy).34

Russia will certainly try to make use of this distrust of official information to set Europeans and Americans against each other. In April 2017, for example, a Russian news agency carried an entirely fictitious report that “three dark-skinned American soldiers” had been detained and then released without punishment after violently attacking a Polish man who tried to prevent them sexually assaulting a Polish woman.35 On that occasion the story was quickly identified as a fake and debunked. In the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s efforts to divide Europe and North America were generally unsuccessful. Public opinion was inclined to trust solidly Atlanticist political establishments. Is that still true today?

For Europeans, build closer ties with other liberal democracies and pro-trade countries. Europe needs a hedging strategy, in case it turns out that Trump is not a one-off, but a reflection of deeper changes in the US’s view of itself and its place in the world. Even if American politics returns to the mean after Trump, the damage he is doing to transatlantic trust and international institutions may take a long time to repair. The 11 countries left behind when Trump pulled out of the TPP have shown the way, quickly renegotiating and signing a slightly less ambitious free trade agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The EU already has free trade agreements in force or under negotiation with eight of the 11 signatories of the new pact. In addition, in recent years it has strengthened its political ties with Canada, signing a Strategic Partnership Agreement formalising foreign policy co-operation.36 It has signed a similar agreement with Australia, and is negotiating one with Japan.

The US continues to play a central role in co-ordinating foreign policy action by like-minded states, as it has shown with the recent air-strikes on Syrian chemical weapons facilities. But Europeans should not assume that the US will always be willing to act when its own interests are less engaged than those of others; the EU should also be more willing to take the initiative and to corral like-minded states to defend the international order, even if for the foreseeable future it will be far less capable than the US.

Conclusion

The partnership between the US and Europe has survived many troubled periods in the past. The US opposed the Anglo-French intervention in Suez in 1956, threatening the UK’s financial stability. General de Gaulle withdrew France from NATO’s integrated military structure in 1966 and forced the alliance to move its military and political headquarters to Belgium in 1967. The US and its allies did not see eye-to-eye over the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in the early 1970s – though the Helsinki Final Act that it adopted was ultimately an important instrument in undermining Communist rule in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. There were tensions over the deployment of US intermediate-range nuclear missiles to Europe in the 1980s. President Bill Clinton was often at odds with European leaders over the war in Bosnia in the 1990s. And the 2003 invasion of Iraq created deep fissures between allies, setting the US, UK, Spain, Portugal and Central European members of NATO against France, Germany and a number of others.

After each crisis, the US and the Europeans have patched up their differences and gone back to working together in pursuit of their shared interests. Why should it be any different in the era of Trump?

Indeed, it may turn out that 2017-21 (or 2025) is just another blip, a brief disturbance in a century of American engagement in Europe’s security. Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric disguises the fact that what he does is often similar to what his predecessors have done. He is not the first president to put pressure on European and Asian allies to do more for their own defence; to use trade defence measures against allies as well as adversaries; or to come to power promising to reduce America’s foreign entanglements and focus on domestic investment.

But Trump’s predecessors were often acting in a context where economic, security and social factors were pushing Europe and the US towards each other. That is no longer the case. There are more factors to widen the Atlantic divide, and fewer to narrow it, than during most previous crises. And – unlike his predecessors – Trump shows little personal engagement with most of his European partners; his relations with Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping seem warmer than with Merkel or even May. Other parts of the US administration can compensate to some extent for the president’s indifference or hostility to transatlantic ties, but in the end Trump sets the tone.

Many in Congress and US civil society and in Europe still see the importance of transatlantic partnership. For them, as long as Trump is in office, the task is to keep reminding public opinion, and perhaps at times each other, that the underlying interests of Western democracies have not changed. Trump and those who share his world view have sounded a loud warning to Atlanticists not to take relations for granted; but it is not (yet) the end of the world as we know it.

17: Pew Research Center, ‘Europe’s growing Muslim population’, November 29th 2017.

Ian Bond, director of foreign policy, Centre for European Reform, May 2018

View press release

Comments