The EU budget after Brexit: Reform not revolution

- The EU is beginning to craft its financial framework (Multiannual Financial Framework or MFF) for 2020-26. The Commission will make its formal proposal in May.

- The EU should make up for the loss of the UK’s annual net contribution of about €10 billion per year with a balanced combination of spending cuts and increased revenue.

- Rebates enjoyed by selected member-states should be scrapped, as they make the budget less just and less transparent.

- The EU should spend more on areas where it truly adds value, such as advanced research and educational exchange programmes.

- Polls show that terrorism and immigration are European citizens’ most pressing concerns, but the EU budget does not address these fears well. The EU should therefore commit more money to border security.

- It would cost about €40 billion over seven years to provide enhanced border security, fund more advanced research and enable twice as many young people to study abroad through the Erasmus programme.

- If there is to be a balanced combination of spending cuts and increased contributions from member-states after Brexit, the EU would have to reduce spending in other areas in order to spend more on education, border security, and research.

- Cutting the EU’s two biggest programmes, Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) direct payments and structural funds, by €80 billion over seven years (about 13 per cent) would make the maths work.

- However, the programmes that are cut can go further with a smaller budget if the EU implements minimal national co-financing for the CAP, and uses more loans and fewer grants for structural funds.

- For political reasons, member-states are unlikely to agree to plans for new EU revenue streams, such as a financial transactions tax or a motor-fuel tax. The EU will have to make the most of its current funding system.

- If member-states want the EU to carry out its current range of activities and take on new challenges, they have to accept that post-Brexit income will be inadequate to cover costs. They will have to increase the percentage of national income devoted to the EU budget from 1.02 per cent of gross national income (GNI) to 1.12 per cent. Even so, in this scenario spending would fall in absolute terms after the departure of the UK.

- The EU agreed in the current MFF to allow more flexibility in how the budget was used, in order to deal with unforeseen events. It should further relax the rules for moving money between MFF spending categories, and allow minor modifications of MFF spending ceilings after they are set.

- If member-states can be convinced, it would also be beneficial to replace the seven-year budgetary cycle with a five-year cycle.

Every seven years, the European Commission puts forward a plan for the EU’s next budget cycle, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). Discussions on the next MFF have begun, and will become increasingly serious in the coming months.

The current MFF covers the period 2014-20 (inclusive)and sets an expenditure ceiling of €1.09 trillion for those seven years. Every seven years, experts remark that, this time, finally, in light of this or that development, Europe should reassess its spending priorities. In 2003, ahead of the ‘big bang’ enlargement of 2004 when ten Central European and Mediterranean countries joined the EU, Brussels commissioned the ‘Sapir report’.1 Its authors called the EU budget a “historical relic”, the bulk of whose spending supported the agricultural sector while economic growth and convergence were neglected. Like most such recommendations, it went unheeded.

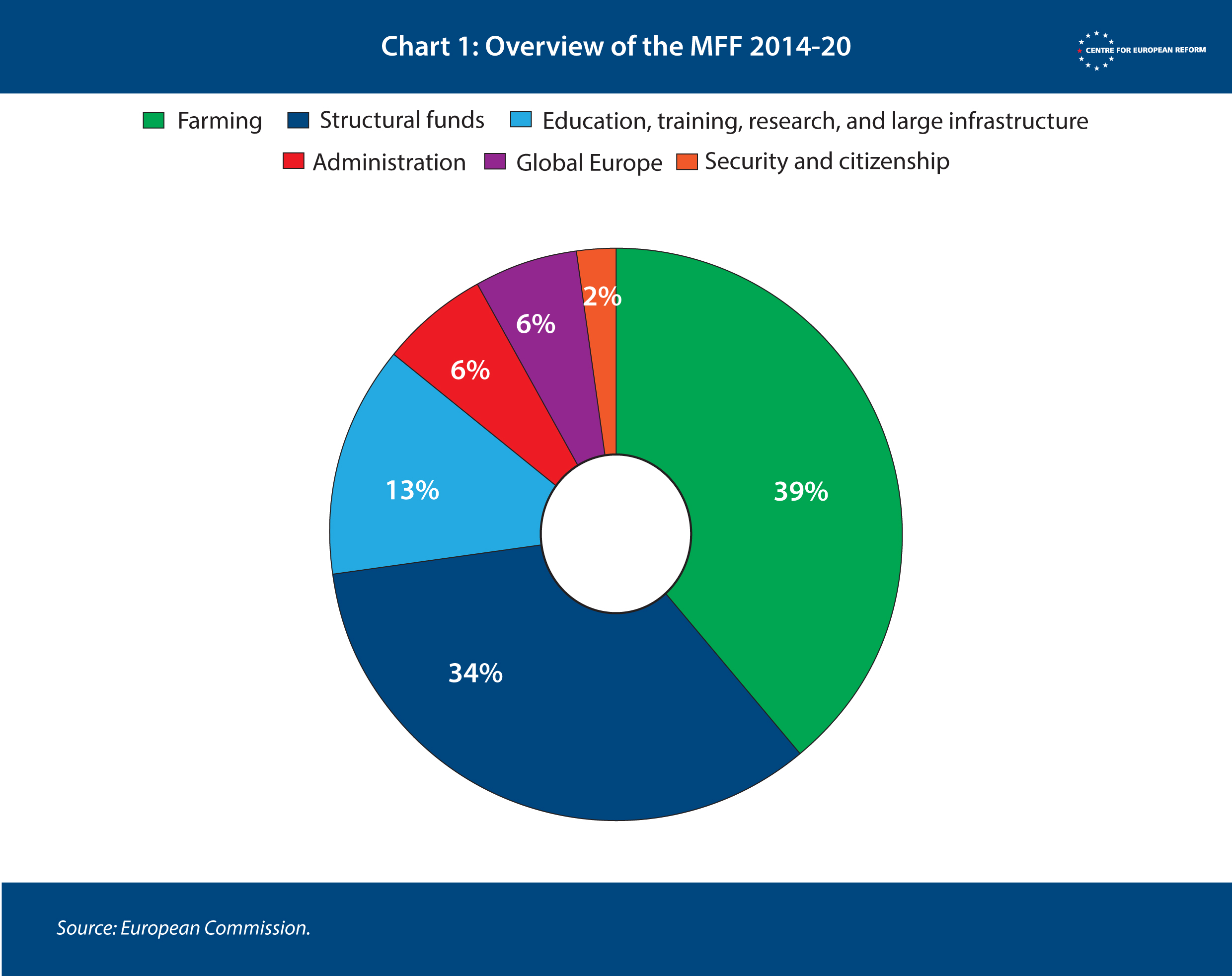

Of course, the EU budget has evolved over the years: the proportion spent on agriculture has fallen since the 1980s, when such payments made up 70 per cent of the budget, as opposed to 39 per cent today, and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been slowly reformed. But radical restructuring of the budget is extremely difficult. Most of the EU’s income is in the form of lump-sum transfers from the member-states, based on the size of national economies. Because member-states’ money is at stake, and every reform would create winners and losers, the path of least resistance is to stick close to the status quo, and muddle through. Most national treasuries still tend to focus on getting a fair return, or juste retour, for their contributions, as if European integration were a zero-sum game.

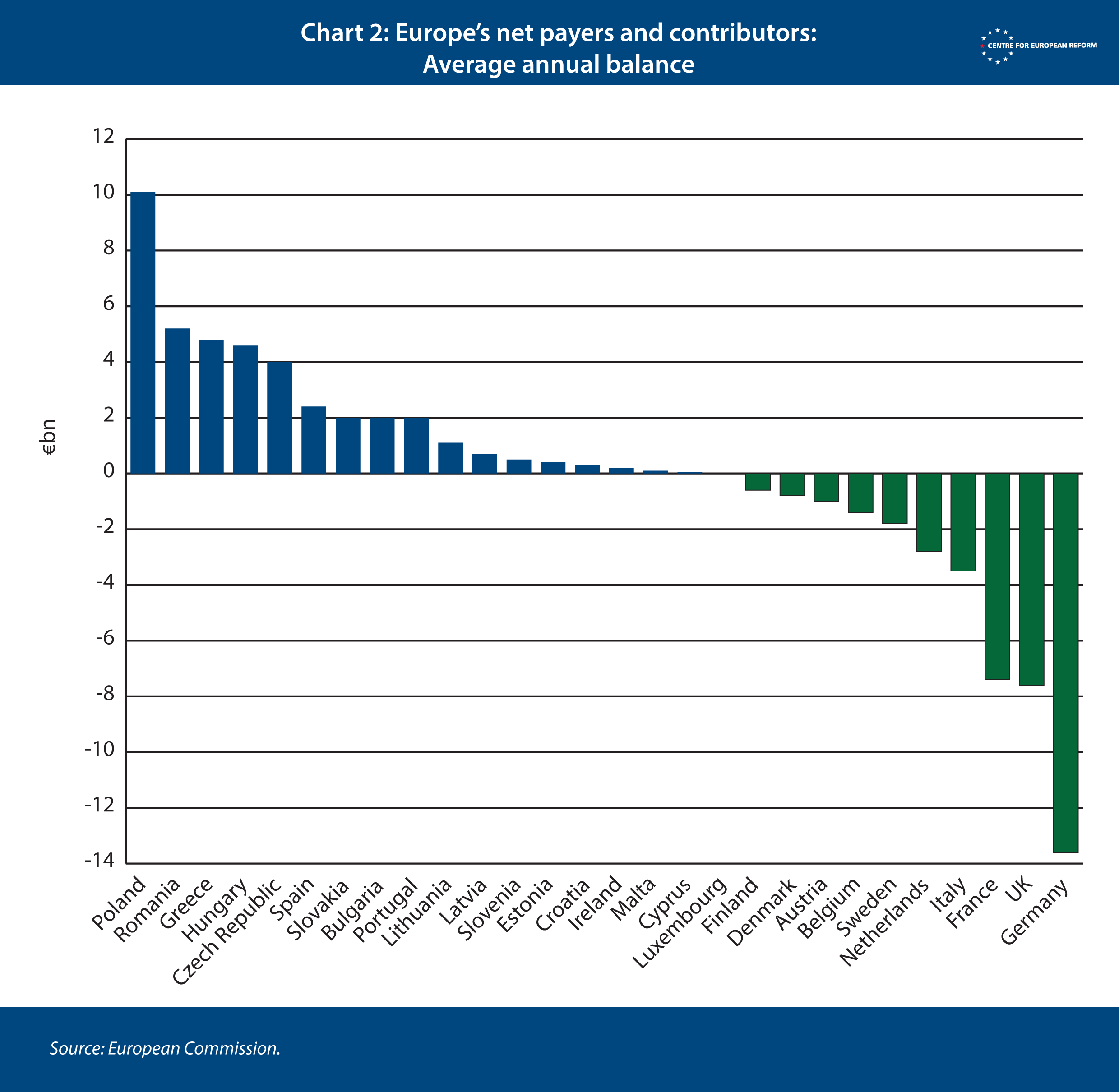

The departure of the UK, a major net contributor, makes crafting this MFF even more difficult. Either the budget will shrink, forcing member-states to accept cuts in payments from the EU; or other net contributors will have to pay more, at the risk of increasing euroscepticism in their countries; or recipients and contributors will have to share the pain, leaving no-one completely happy.

It is unrealistic to think that there will be radical changes in this MFF, beyond any that Brexit forces on the EU-27. The Council, the European Parliament and national parliaments are unlikely to give their unanimous approval to cutting the CAP by half; or to an EU financial transactions tax that would hit countries with big financial services sectors disproportionately. So this policy brief explores how the MFF could change incrementally and still serve Europe better. The aim is not to come up with exact euro amounts for each policy area, but rather to guide readers through the budgetary debates and highlight advantageous reform proposals.

The first section explains where the EU gets its money from and what it currently spends it on. The second lays out the positions of Brussels institutions and the member-states for the forthcoming negotiations. The third proposes how to use the MFF to achieve more of the EU’s priorities after Brexit.

The state of play

Each MFF sets spending limits for a period of seven years, both overall and for broad policy areas, leaving detailed amounts for individual policies to be negotiated in the annual budget talks. These commitments are firm: the EU cannot borrow to finance its budget, and there is very limited room to change the ceilings once they have been set. More flexible EU spending that is determined outside the MFF negotiations, such as a solidarity fund for natural disasters and a fund for workers hurt by globalisation, amounts to no more than €1.5 billion a year combined. (Some other sizeable funds are also set up outside the EU budget. The most significant of these is the European Development Fund, which allocated €30.5 billion in external assistance for the period 2014-20. It is run on a separate budgetary cycle with a different scale of contributions, and focuses on African, Carribean, and Pacific countries, as well as EU overseas territories.)

From 2014 to 2016 the EU spent an average of €141 billion annually.2 €41.5 billion or 30 per cent of that was direct payments to farmers under the CAP. Another €11.8 billion or 9 per cent went to the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development. The next big-ticket item is what Brussels calls ‘structural funds’, which amount to €47.8 billion per year. For the most part that means the EU giving money to member-states and regions, especially poorer ones, to fund promising local initiatives and build new energy or transport infrastructure. The EU also uses structural funds to give grants to small businesses that want to invest in improving their competitiveness. Then there is Horizon 2020, the EU’s major research and innovation programme, at €9.2 billion. From 2014-16 the EU spent €306 million annually on the asylum, migration and integration fund; and €353 million on the internal security fund.

Other major expenditures include the Erasmus education programme (€1.8 billion), large infrastructure projects such as satellites and the ITER experimental fusion reactor (€1.8 billion), and ‘Global Europe’ (€8.5 billion), which encompasses the Common Foreign and Security Policy, humanitarian aid, development aid (in addition to the European Development Fund), and the funds for programmes for the EU’s neighbours and candidates for membership. Administrative and staff costs account for 6 per cent of the total.

A sense of scale is useful. The EU budget is small, equivalent to only about 1 per cent of GDP across member-states, or 2 per cent of public spending. The most expensive services that governments provide, like healthcare, remain the province of national governments. The budget is also too small for significant counter-cyclical economic ‘stabilisation’, when governments boost spending or cut taxes to counteract falling private sector spending.

Small does not mean unimportant. In Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, for instance, transfers from the EU amount to over 4 per cent of GDP.3 In Portugal, Croatia, Lithuania, and Poland, EU structural funds make up over 60 per cent of public investment.4 For some citizens, the EU is most visible when it is funding a new highway for their commute or an Erasmus scholarship for their child.

Despite the claims of eurosceptics that the EU is a wasteful mess, the European Court of Auditors (ECA), the independent body that reviews EU finances, estimated that only 3.1 per cent of EU spending was affected by error in 2016. This is “money that should not have been paid out because it was not used in accordance with the applicable rules.”5 Examples include awarding contracts without a proper bidding process, or a recipient unintentionally claiming costs for which they are ineligible. National governments manage 80 per cent of the money in the EU budget and are responsible for some of these errors.

Fraud, on the other hand, is deliberate deception to gain a benefit. In 2016 the ECA forwarded 11 instances of suspected fraud to the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF),which reported that €631 million (less than 0.5 per cent) was fraudulently misused and should be recovered.6 By comparison, the UK National Audit Office found that 6.2 per cent of UK tax credit payments in 2016 were marred by fraud or error.7

Where does the EU get the money from? It takes a percentage of each member-state’s income from value added tax (11 per cent of revenue in 2016) and levies customs duties on imports (14 per cent). The largest source of revenue (67 per cent) is called own resource based on gross national income (GNI): each member-state transfers a standard percentage of its yearly gross national income to the EU. Germany pitched in €20.6 billion in 2016; Cyprus just €111 million.8 These main sources of revenue are currently not permitted to exceed 1.23 per cent of EU GNI.9 In practice, revenue is calculated to cover planned spending, and spending is always below that legal revenue ceiling: from 2014-15 spending was 1.02 per cent of GNI.

In some smaller member-states, EU structural funds make up more than 60 per cent of public investment.

Additionally, the EU earns about 5 per cent of annual revenue from fines on companies, interest on late payments by member-states, and contributions from non-EU states like Norway and Israel to specific EU programmes such as Horizon 2020.10 Sometimes, the union rolls over an underspend from the previous year; this averaged €4.3 billion annually from 2014-16.

There are three stages to the MFF process. In the current pre-negotiation phase the Commission has published several papers on the budget and launched a public consultation, while the informal meeting of European heads of state and government in February 2018 discussed the political priorities for the budget. Next is the negotiation phase between member-states, which begins when the Commission publishes its draft proposal, which it has promised to do in early May 2018. Member-states then deliberate in the General Affairs Council before heads of state eventually come to a political agreement and publish a document detailing desired spending amounts.

The final phase is negotiations between the European Council and European Parliament. Last time around the Parliament was unable to get the European Council to increase the overall size of the MFF, but it persuaded member-states to allow more switching of money between spending categories and to undertake a serious mid-term review in 2017. Once the presidents of the European Council, the Parliament, and the Commission reach an agreement, the MFF regulation can be prepared. Parliament gives its formal consent, and the Council votes unanimously to adopt the document.11 For the 2014-20 MFF, that vote took place quite late, in December 2013. The delay had real negative consequences: 25,000 Erasmus exchanges could not take place in 2014, and some EU funding for border management and asylum-seeker reception did not arrive until 2015.12

Negotiating positions

What Brussels is saying

The European Commission will not present its official proposal for the next MFF until May, but commissioners and national leaders have already made their broad preferences clear. As usual, EU officials want more money from the member-states, and the member-states want a leaner budget.

The most pressing issue is how to make up for the absence of British money after 2020. While Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson has exaggerated the size of the UK’s contribution, driving around in a bus suggesting the UK could “take back control” of €18.2 billion per year, the UK does send around €10 billion per year more to Brussels than it gets back in the form of EU spending in the UK, such as payments to public sector bodies and farmers, and grants to the private sector.13 (For example, from 2007-13 the EU spent €65.5 million to improve high-speed internet access in Cornwall).14

Some analysts argue that the UK’s annual net contribution is higher, around €12 billion. In its calculations, the UK Treasury does not take into account funds allocated directly to non-governmental UK organisations by the Commission; a House of Commons study puts the annual net contribution from 2014-17 at €11.5 billion.15 The UK’s contributions are fairly volatile, as they are susceptible to exchange-rate fluctuations. And all member-state GNI-based contributions can grow or shrink depending on changes in EU spending and the other sources of EU revenue, such as customs duties. In any case, the vast majority of the UK’s contribution will disappear at the end of Britain’s transition period, even if the country agrees to make a financial contribution in order to take part in EU programmes covering security co-operation or research.

The transition deal to which the UK has agreed still foresees some UK payments in the next MFF, for current projects continuing past 2020.16 Furthermore, beyond 2020, the UK may wish to continue to support certain EU activities. British Prime Minister Theresa May said in March that the UK wants a “science and innovation pact… that would enable the UK to participate in key programmes” like Horizon 2020. She will “take a similar approach to educational and cultural programmes”, and “wants to explore … how the UK could remain part of EU agencies such as those that are critical for the chemicals, medicines and aerospace industries”.17

A possible model for the UK is the arrangement Norway has with the EU. Norway is a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), and as such pays to participate in a number of EU programmes and agencies, including Horizon 2020 and the Erasmus programme. Those contributions appear as MFF revenue.18 One of the other obligations of an EEA member-state is to give significant sums to poorer EU member-states. While not formally part of MFF revenue, those contributions reduce the burden on the EU budget. In return, EEA member-states get single market membership. But May has said the UK will leave the customs union and single market, which rules out EEA membership.

The UK sends around €10 billion per year more to Brussels than it gets back. This is the Brexit gap.

EU budget Commissioner Günther Oettinger has proposed closing the Brexit gap with a “50/50” approach, ie 50 per cent ‘fresh money’ and 50 per cent cuts to existing programmes. On the cuts side, he has suggested reducing the percentage of the budget devoted to the two biggest spending areas, known in EU jargon as Smart and Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Growth: Natural Resources. The former is essentially infrastructure and development funds; the latter the CAP. Oettinger would reduce these budget lines, which currently account for around 35 per cent of the budget each, to 30 per cent each.19

The Commission’s communication before the first, informal European Council discussion of priorities for the MFF gives a better sense of what such cuts might look like – though these are options for debate rather than final positions.20 For example, at the moment, all EU member-states are eligible to receive money from the European Regional Development Fund (support for research, small business and low-carbon projects) and the European Social Fund (employment related-projects). The communication asks whether this support should be limited to regions whose GDP per capita is less than 75 per cent of the EU average. In this scenario, France, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and much of Italy and Spain would stop receiving money from these structural funds, freeing up €95 billion over a seven year period, or 8.7 per cent of the current MFF.

According to recent reporting, the Commission may propose a more radical revamp of the allocation of cohesion funds, which are meant for the poorer member-states.21 Rather than distributing cohesion money almost solely on the basis on GDP per capita, Brussels would like to consider broader criteria such as youth unemployment, education levels, and even the number of migrants in a region. This change would have the effect of redirecting funds from Poland, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states to Greece, Spain and Italy, whose economies were battered in the financial crisis and which have had to deal with a disproportionate number of refugees and migrants from the Middle East and North Africa. It would open up another front in the pitched battle over who gets Brussel’s money. However, the Financial Times also reports that the Commission may put in a ‘safety net’ to limit the short-term gains and losses that any one member-state could achieve or suffer.

As for the CAP, the February communication considers cuts of between zero and 30 per cent. Noting that 80 per cent of CAP payments go to 20 per cent of farmers, it alludes to the recommendation made in the Commission’s 2017 CAP reform document, to limit the amount of subsidies that the largest farms receive – in other words, capping the CAP.22 While CAP and structural funds might go under the knife, Oettinger has said he wants to protect the Erasmus programme and Horizon 2020 research from any cuts.

The Commission also wants more money for new priorities. Foremost among these is border security. In the current MFF, the European Border and Coast Guard, also known as Frontex, receives €4 billion over seven years to employ around 1,000 staff and co-finance national border security operations. The communication envisages three scenarios for the organisation’s expansion. The funding could be simply doubled to €8 billion. Or the EU could expand the mandate for Frontex, giving it more equipment and enough money to employ a standing corps of 3,000 border guards. This would cost at least €20 billion over seven years. Alternatively the EU could set up a massive border management system on the American model, with 100,000 employees and a budget of €150 billion.

New sources of revenue would make it easier to fund new programmes. If the revenue system remains unchanged, the ‘fresh money’ would have to come in the form of bigger lump-sum contributions from the member-states: those levies are determined by how much money the EU still needs after it has received customs and VAT revenue. The Commission would like new resources to “forge an even more direct link to Union policies”.

The most detailed report on new revenue came from an EU group chaired by former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti, which proposed to reduce the percentage of national income each member-state hands over to Brussels. The group argued that, instead of large lump-sum transfers, member-states should levy certain taxes, the proceeds of which would go in part to Brussels. Options included a carbon tax, a corporate income tax, and a financial transactions tax.23 All of the Monti reforms would face significant resistance from member-states and affected interest groups, as another expert study commissioned by the Commission detailed.24 There would be clear winners and losers. A financial transaction tax would hit Luxembourg, a banking hub, harder than Bulgaria. Poles would spend proportionally more of their income on a motor-fuel tax than the greener Dutch. And these new taxes would have to secure unanimous support in the Council, as well as the approval of national parliaments.

The Commission’s February communication says only that the Monti report is “still being looked at” and proposes some other options. (The Commission’s original proposal for the 2014-20 MFF foresaw a financial transactions tax; this went nowhere.) The proposal winning the most media attention is for the EU to take a share of the revenue that central banks earn by issuing money, known as seigniorage. A change to the European Central Bank’s statute would allow the bank to redirect those profits away from eurozone central banks to the EU; EU officials estimate this would generate €56 billion over seven years. However, this leads to the same political problems as any other new form of taxation, and it is unclear whether non-eurozone countries would also have to hand over their seigniorage.

It is no surprise that the institutions see a need for more money. The European Parliament must give its consent to the MFF. Its budget committee has put out a wish list: it would like to ‘cover the Brexit gap’ by implementing new taxes such as a financial transactions tax or environmental taxes and to boost spending on student exchanges, research, and infrastructure. Beyond that, the Parliament wants a five-year budget period, the end of all rebates and greater flexibility.25

Oettinger is asking for expenditure a bit higher than 1.1 per cent of GNI, compared to the current 1.02 per cent. President Juncker wants more than 1 per cent too. The EU, he says, is worth “more than a cup of coffee per day.”

What member-states are willing to pay

There are vastly different views on the EU budget within member-states, and even within governing coalitions. But it is possible to identify which member-states would be willing to contribute more money after Britain leaves. Wealthier member-states pay more to the EU than they receive back in EU spending, and are traditionally wary of increasing their obligations. But the debate is not as simple as net contributors versus net recipients. Four net payers are taking a hard line against any increase in spending as a percentage of GNI. Some journalists call this group the ‘frugal four’: Austria, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands do not want to increase their contributions. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte says “my goal for the multi-annual budget is this: no increase in contributions, but better results within a smaller budget.”26 Swedish Finance Minster Magdalena Andersson told the Financial Times that the Brexit gap is “not a hole… [The Brits] are not there anymore, so of course we have to shrink the budget.” 27

Macron has big plans for the next MFF. France is ready to contribute more money if the EU reforms.

Small-budget advocate Britain will obviously have no say in this debate, but the frugal four might be surprised by the defection of one traditional budget hawk: Germany. According to the coalition deal agreed between the SPD and the CDU/CSU, Germany’s next government is “ready for higher German contributions to the EU budget.”28 The Germans, though, have plenty of ideas about how their higher contributions should be used. Angela Merkel told the Bundestag that more EU money should go into structural reforms and investment, and that Frontex should be “massively improved”.29

Some figures in the German government also advocate tying the receipt of EU cohesion funds to respect for the rule of law – neighbouring Poland is in the crosshairs – and propose to reward those member-states, such as Germany, that accept large numbers of refugees, with extra cohesion funds. Both ideas could well make it into the Commission’s forthcoming draft proposal.

Finally, Berlin, like The Hague, believes the EU should use the MFF to encourage member-states to carry out structural reforms (such as making labour markets more flexible; or simplifying tax systems and regulations).30 Other countries agree; the Commission’s reflection paper on EU finances suggests using the Cohesion Fund, which aims to reduce disparities between member-states, to reward countries that undertake difficult economic reforms.31 This would complement the technical support provided through the Structural Reform Support Programme, founded in 2017.

While the official Italian position will not be clear until a governing coalition is formed, French President Emmanuel Macron has big plans for the next MFF and envisages a bigger budget. He wants to make cohesion funds conditional on member-states levying a certain corporate tax rate – Paris does not want a ‘race to the bottom’.32 He wants to create European universities and a new programme to help local authorities host and integrate refugees, and says “we need to provide dignified funding for European defence and for migration”.33 Macron has also advocated EU-level taxes in the digital or environmental field. Most importantly, he told the European Parliament that France is ready to increase its contribution if the EU “recasts the budget”.

What about l’agriculture? The French have traditionally supported larger farm subsidies: when the European Economic Community created a common market in the 1960s, France insisted on agricultural subsidies. Because France is now a net contributor to the programme (though still the largest recipient in gross terms), some have suggested France might be ready to cut the CAP drastically, to slaughter its sacred cow.34 A leaked French government document urged Brussels to reduce overall spending after Brexit by undertaking “a deep reform of the oldest [MFF] policies”. But reform is unlikely to mean radical reductions in funding. In a January speech on agriculture, Macron said the CAP “cannot have a less ambitious budget”, and only spoke in favour of a “less bureaucratic CAP” with better support for rural development.35 Already accused of being the president of wealthy urban elites, Macron can only take on so many interest groups at once.

The EU’s newer member-states do not want Brexit to prevent the EU from funding Central Europe’s priorities. The Visegrad four (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia) together with Croatia, Slovenia, and Romania, have released a statement saying that a larger MFF in terms of percentage of GNI (1.1 per cent) should be “taken into consideration” and that new programmes should not come at the expense of cohesion funds – from which these member-states benefit greatly.36 Vast farm co-operatives have endured in some member-states, like the Czech Republic and Slovakia, so they oppose capping the CAP funds that large farms receive. Polish ministers have fiercely attacked plans to make structural funds conditional on compliance with the rule of law, which they see as designed to penalise Poland.37

A eurozone budget could become part of the next MFF, depending on whose vision wins out. Macron’s government would prefer a sizable standalone eurozone budget, separate from the MFF, financed via a contribution from corporation taxes and possibly also debt issuance. German conservatives may accept a small ‘eurozone investment capacity’ to boost economic convergence, but are unconvinced of the need for a eurozone instrument that provides hand-outs to prevent or resolve a crisis, or a large one that has macroeconomic significance.38 Juncker has suggested that the EU create a dedicated line for the eurozone within the MFF; this idea has a better chance of becoming reality before 2020.39

Greece, Spain, Ireland, and Bulgaria also appear willing to countenance higher spending as a percentage of GNI.

An MFF that works

The EU needs an MFF that responds to the key challenges the Union faces, and one that different member-states can get behind or at least live with. Here is what the EU should prioritise for the period 2020-26.

Border security

Europe needs to devote more resources to managing its borders. According to an August 2017 Eurobarometer poll, European citizens believe immigration and terrorism are by far the most important issues facing the EU at the moment.40 Control over external borders is a precondition for invisbile internal borders. Tighter border controls will not stop the majority of terrorist attacks, which are carried out by EU citizens or legal residents. Nor should they lead to Europe shutting out people with a legitimate claim to asylum, however unpopular refugees may be in some member-states. But Europeans want the authorities to catch more people-smugglers and keep track of who enters the EU. Migration pressures are not going away.

According to polling, citizens believe immigration and terrorism are by far the most important issue facing the EU.

In the past the EU has relied on front-line states to deal with irregular migrants and refugees. The numbers seeking to enter the EU are now far beyond the capacity of countries like Greece or even Italy to register, process and either admit or deport. The EU needs to make a collective effort, with an expanded border and coast guard. Frontex is funded through the Internal Security Fund, which spent less than €500 million in 2016. Beyond paying border agents, the fund also gives grants to national governments to set up IT systems, train employees, acquire equipment to fight crime and process Schengen visas. The Commission’s suggestion of boosting spending on the Internal Security Fund to €3 billion a year is a good one. The EU’s issues with migration go beyond the scope of the MFF. But as efforts to revise the Dublin regulation (according to which the member-state an asylum-seeker arrives in first is responsible for processing the asylum application) and create a fair system for sharing out migrants stall, more effective border control would be a good start.41 Three billion euros a year corresponds to 2 per cent of the current MFF.

Education and research

Security is far from the only area that needs more resources. Commission officials love to repeat their budget buzzwords, ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘value-added’. Education and research are two areas where the EU can achieve things that member-states on their own cannot. The Commission has set out a vision for a European Education Area by 2025, including technical changes like smoother mutual recognition of high-school leaving diplomas. But the MFF is about money. According to Commission estimates, the EU could double the number of young people who receive training or study abroad through Erasmus by increasing the programme’s funding from €1.8 billion a year to about €4 billion a year. For an organisation that spends €40 billion a year on direct payments to farmers, that does not seem like too much to ask. Economic research shows that studying abroad increases an individual’s probability of working in a foreign country.42 Low labour mobility is, at the moment, one of several ways in which the eurozone differs from single currency areas like the United States: a recent Eurostat poll suggests only 12 per cent of unemployed Europeans aged 20-34 would be willing to move to another member-state for a job.43 It is good for the economy when Europeans are willing and able to move for work because they will move to fill open jobs and thus relieve pressure on areas with high unemployment.

Advanced research is an area in which increased investment would have multiplier effects. The EU spends a lower percentage of its GDP on research and development than China, Japan or the United States.44 None of the world’s ten biggest ‘unicorns’ – venture-capital backed private companies valued at $1 billion or more – comes from Europe. And European tech hubs and computer science education lag behind US counterparts.

The EU could double the number of young people who study abroad by doubling the Erasmus budget, to €4 billion a year.

The rationale for Horizon 2020 is to close this ‘innovation gap’. One advantage of EU funding is that it awards large sums competitively, so money flows to the best research projects in Europe, while national funding is generally smaller and limited to domestic universities and research centres. The Commission reports that its flagship research programme, though underfunded, has been effective: 83 per cent of funded projects would not have gone ahead without help from the EU, it claims.45 Horizon 2020 grants have gone to promising projects like researching how to produce nano-pharamaceuticals, or reduce CO2 emissions from aircraft.

It makes sense to increase the innovation and research budget, but the EU’s finances are under pressure, so it is essential to focus funding on promising areas that, for whatever reason, are hard to fund privately. One possibility is for the EU to further concentrate on early-stage applied research for risky projects far from market viability. Such projects are often too speculative for private investors, but funding them at an early stage can lead to breakthroughs in the technologies of the future. Apple’s voice-controlled personal assistant, Siri, for example, started out as an experimental project supported by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) of the United States. The creation of an EU DARPA is another Macron-backed idea; a report on innovation from the Jacques Delors Institut points out that such an agency could go beyond a similar EU pilot initiative, the European Innovation Council, and focus on advanced civilian technologies like simultaneous translation into the 27 European languages.46 For €1.5 billion a year, the EU DARPA could have a budget half the size of its American counterpart, which would be a good start.

DARPA, as the name suggests, puts on a strong emphasis on products with military applications. The next MFF will also need to set aside money for the European Defence Fund. Launched in 2017, the fund is meant to make available €1.5 billion a year from 2020 for collaborative research and joint development and acquisition.47 After years of talk about the need for Europe to take more responsibility for its own defence, there will finally be a defence line in the EU budget.

Flexibility

For an organisation bound by strict spending limits and forbidden from borrowing, the EU is reasonably flexible in a crisis. It is important to have flexibility because problems can arise that the Commission did not foresee: in 2013, no one could predict how many refugees and migrants would come to Europe in 2015. Thanks to new flexibility instruments created for the current MFF, and strengthened in the 2017 mid-term review, the EU has been able to shift money between headings and years to a greater extent than before. In 2014 it supported farmers affected by Russian sanctions on EU dairy products, and funded the Juncker investment plan, whose aim was to guarantee loans for higher risk European Investment Bank projects, stimulating extra private investment. In the period 2016-19 the EU has stumped up €440 million from the Flexibility Instrument to care for refugees in Greece.

There are nevertheless limits to the EU’s ability to adapt. ‘Frontloading’ (spending money designated for later years) does not work at the end of a budget cycle, as the EU cannot take money from an MFF that is not agreed yet. Moving money from Horizon 2020 to the Juncker plan’s seed capital presented its own problems – spending on clearly economically beneficial research was cannibalised support for higher risk projects like improving a Greek broadband network, when most of the projects funded by the Juncker plan would have gone ahead anyway.48 Because of MFF constraints, the Facility for Refugees in Turkey had to rely on €2 billion from member-states as well as the €1 billion it received from the EU budget – and now a fight is brewing over who should pay for the next tranche.

These issues have led to calls for new tools to deal with unforeseen crises. A study written by Eulalia Rubio of the Jacques Delors Institut for the European Parliament examines the two most direct options: an EU crisis reserve, funded by money meant for cancelled projects (a proposal that is favoured by the Commission); and setting aside 5 per cent of the budget every year for unexpected events.49 The problem is that a reserve funded by cancelled projects and fines on member-states for late payments would require a rise in the revenue ceiling, in case the amount taken in was especially large in a particular year; it could also create perverse incentives for the Commission to cancel projects in order to free up money for other things. The Council rejected the Commission’s proposal for such a reserve in 2017. Meanwhile, a fixed annual reserve would reduce the amounts available for pre-determined spending at a time when Brexit is straining EU resources. If there is to be a non-programmed reserve, it will have to be relatively small.

Several member-states are interested in making structural funds conditional on respect for the rule of law.

Rather than creating a reserve, the EU should use technical fixes to make the budget more flexible. The EU could merge some spending categories and further relax the rules for moving money around between categories. Rubio’s study proposes that the Council should be able to modify MFF ceilings by a qualified-majority vote, by up to 0.03 per cent of EU GNI (almost €5 billion in 2016).

Length of budget cycle

If member-states can be convinced, it would also be beneficial to replace the seven-year budgetary cycle with a five-year cycle. This would align the budget with the terms of EU parliamentarians and the Commission president, and allow more substantial revisions after five years. Commission Spitzenkandidaten (lead candidates at the head of the European parties) could explain to voters how they would manage the annual budgets for their five -year term and shape the MFF for the following five years. MEPs would be able to exercise one of their greatest powers, budgetary oversight, more frequently. Member-states have, on the whole, shown little interest in making this change.

Conditionality

One of the innovations of the last MFF was ex-ante conditionality on structural and investment funds. Those conditions were a mixture of economic (not exceeding deficit targets) and institutional (a country could not get funds for an environmental clean-up if it did not have a legal framework for the activity and an institution to carry it out). But compliance with the rule of law is a growing problem in a number of member-states, and several countries are interested in extending ex-ante conditionality to cover rule of law problems.

The current mechanism for punishing rule-of-law violations under the Treaty on European Union requires the other 27 member-states to unanimously decide that a “serious and persistent breach” of EU values has occurred, opening the door for a suspension of the offender’s voting rights. But most member-states are loath to use this ‘nuclear option’. Therefore making structural funds conditional on respect for the rule of law might be a more effective tool than the suspension of voting rights. The justification for using economic leverage is that member-states that flout EU values and have compromised legal systems are unlikely to be able to use EU funds effectively, because corruption will flourish and investors will flee. Losing investment reduces economic growth and thus reduces convergence with richer countries, contrary to the aim of structural funds.

As a first step, the EU should empower its Fundamental Rights Agency to assess the rule of law in individual member-states periodically. Countries of concern could then face enhanced monitoring, or be asked to implement Commission recommendations. In case of extreme breaches of European values, the EU could suspend funds meant for the offending national government and instead reroute the money to municipal governments, NGOs, or even via a Commission body, in order to avoid unduly punishing individual citizens and possibly stirring up euroscepticism. Member-states would have to agree unanimously to write rule of law conditionality into the next MFF regulation – a heavy lift given Hungary’s and Poland’s disputes with the Commission, to say the least – but the EU has previously reached a consensus to tie structural funds to conditions in other policy areas.50

Rebates

The simplest way of softening the Brexit blow is to simplify the revenue side of the budget. The UK’s rebate is meant to be evenly covered by increased contributions from the other 27, based on their share of EU GNI. But since 2002 Germany, Sweden, Austria, and the Netherlands have benefited from a permanent reduction (75 per cent) in the amount they pay to give the British a rebate – the so-called rebate on the rebate. In the current MFF, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Austria also enjoy lump-sum reductions to their GNI-based contributions; and Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden hand over less of their VAT revenue than other states.51 These ‘correction mechanisms’ make the EU budget less transparent and less fair. As Oettinger has said, the EU “should not only do without the mother of all rebates but without all of its children as well.”52 The Commission will propose to scrap these rebates, but it remains to be seen how member-states will respond. Rebates are politically important in the countries that get them.

The budget for the CAP should diminish in order to release money for new priorities, like advanced research.

Savings

The Commission should stop spending over €1 billion per MFF to shuffle MEPs between Brussels and Strasbourg, which is a terrible advert for the EU. It is highly unlikely that France will be willing to sacrifice the Parliament’s Strasbourg seat, however.

Member-states should be wary of proposals to restrict structural funds to poorer regions whose GDP per capita is less than 75 per cent of the EU average. Brexit will already entail a greater burden for the richer member-states, so it would be politically problematic to deprive them entirely of EU support for their poorest regions. One can imagine tabloids in Germany and the Netherlands reprinting the Commission’s structural fund maps from its February 2018 paper, which show citizens in those countries receiving nothing.

The budget for structural funds should shrink somewhat, however. Consequently, a small number of projects that might have received EU financing had the present conditions continued will not be able to do so in the next MFF. Instead, the Commission envisages financial instruments (loans, grants and equity financing) playing a larger role for structural funds, which could allow a smaller structural fund budget to go further. When loan repayments or guarantees are repaid, they come back into the budget and can be used again in later budget cycles. Loans and the like are only appropriate for revenue-generating projects, such as toll roads, but they are expected to have a leverage effect and attract additional public or private funding for projects that receive EU loans.

The budget for the CAP should also diminish, to release money for new priorities. The modern CAP is divided into two pillars. Pillar 1, by far the larger, is direct payments to farmers and agricultural landowners. A major 2003 reform removed the link between subsidies and the production of particular products, after the old system had encouraged overproduction of certain goods, resulting in the infamous butter mountains and wine lakes. Pillar 2 is the rural development policy, which aims to ensure the “the sustainable management of natural resources”.

Commissioners and member-states are discussing several big reform options for these expensive programmes. The proposal to cap payments to the largest farms has some attractions, but could lead to the break-up of large, efficient agribusinesses. It would be possible to reduce payments to farmers in rich countries – the current formula pays richer member-states more per hectare because of higher labour and land costs. Or ‘voluntary coupled payments’ could be banned: member-states are currently allowed to dedicate up to 8 per cent of direct CAP payments (€3.3 billion annually) to support farmers of specific products who are struggling to stay in business. Beef and veal farmers have been the main beneficiaries in recent years. EU funding should not be used to keep failing businesses afloat.

All of these ideas have their merits. But they also have one thing in common: coalitions of member-states oppose reforms that would disadvantage their farmers. That is not a reason to drop consideration of certain changes, or to leave the CAP out of the grand bargaining process, because a small decrease in agricultural spending for this MFF seems essential. A decrease of 10 per cent on current spending levels would free up over €40 billion over a seven-year period.

One promising reform however, earns only one sentence in the Commission’s reflection paper on EU finances. “One option to explore is the introduction of a degree of national co-financing for direct payments in order to sustain the overall levels of current support”.

As Alan Matthews, a professor emeritus at Trinity College, Dublin, has written, it is odd that Pillar 1 payments are financed entirely by the EU. Structural funds, and the CAP’s Pillar 2, require national co-financing.53 For those programmes, member-states must make a contribution to the programme for which they wish to receive money. Co-financing rates vary according to the programme and the wealth of the region or member-state.

If this were also the case for direct payments to farmers, national ministers of finance would have to think harder about the value of those subsidies. Some national capitals might decide to stop payments to wealthy farmers who own large tracts of productive land. Others would be free to continue making payments if EU CAP funding were further reduced over time, without violating state-aid rules. This too, is an unpopular idea, but spending cuts usually are. Oettinger has spoken of the inconsistencies in, for example, Austria’s opening negotiating position. Vienna refuses to countenance paying more to cover the Brexit gap, but also calls the CAP sacrosanct.

Funding sources and overall funding levels

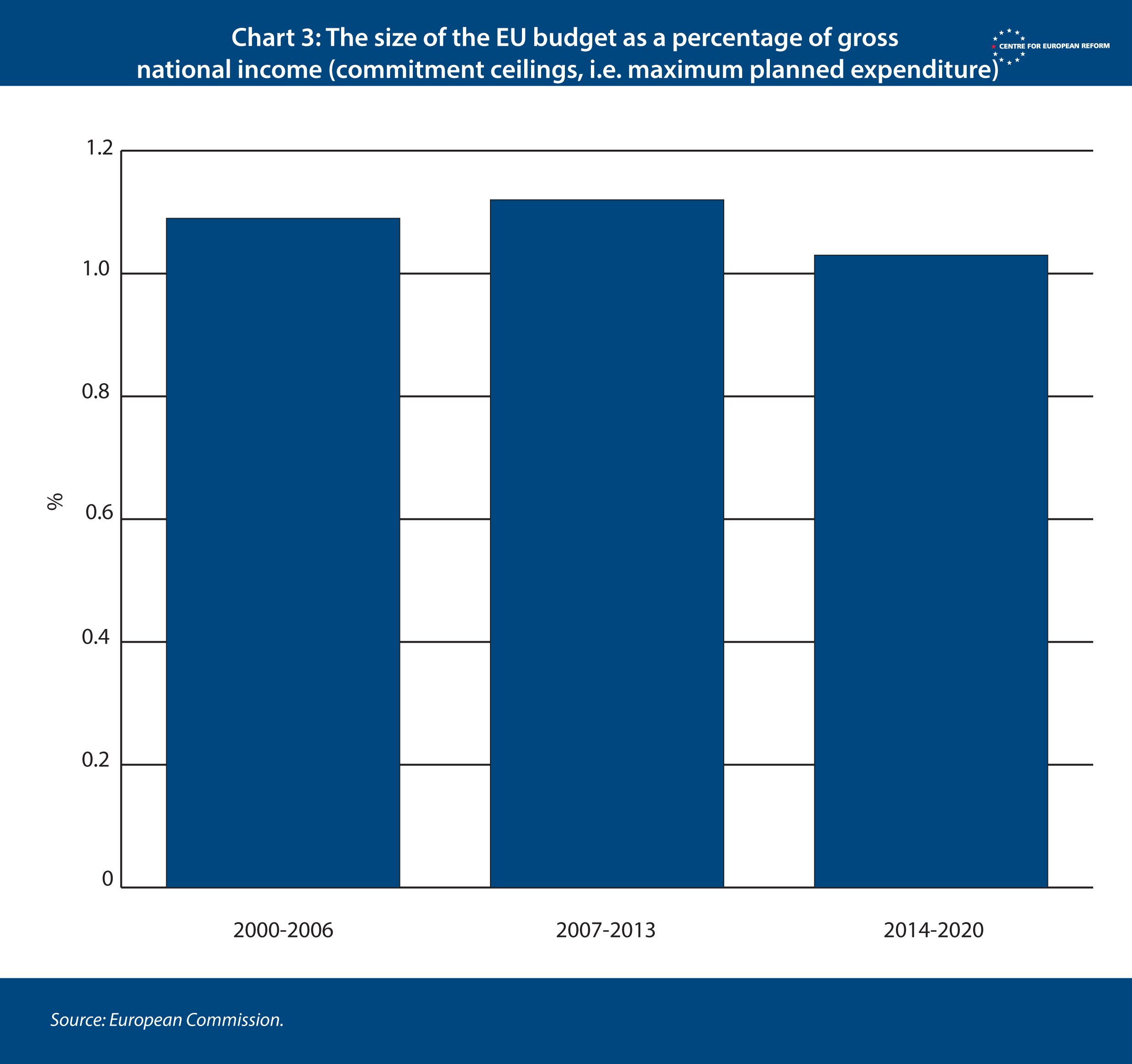

It is understandable that the EU budget should shrink in absolute terms after the departure of Britain, the world’s fifth largest economy and a significant net contributor. But there is a strong case for slightly higher absolute contributions from member-states, and for higher overall spending as a percentage of member-state GNI. (Indeed, the budget’s relative size would rise even if the EU cut €10 billion – the putative Brexit gap – because the UK contributes more to EU GNI than to the EU budget.) Spending for the 2014-20 MFF was low in recent historical terms, as chart 3 shows. It was the first time an MFF was smaller than the previous one. The budget reflected the austerity orthodoxy of the early 2010s; politicians making cuts at home insisted on cuts in Europe.

The EU should look for a compromise between miserly net contributors and needy net recipients that spreads the pain fairly. In 2014-15 the EU budget represented 1.02 per cent of EU GNI. A combination of €40 billion in spending cuts and €40 billion in additional contributions (of around €1 trillion spent per MFF) over seven years would bring the budget to 1.12 per cent of GNI.54 This would leave the union with some headroom before it would reach the ‘Own Resources Ceiling’ according to which the EU may not collect more than 1.23 per cent of GNI in revenue.

The EU should spend a total of €40 billion over seven years on an expanded Frontex, an ‘EU DARPA’, and doubling Erasmus funding. This would necessitate €80 billion (12.8 per cent) in cuts to CAP direct payments and structural funds. There is no denying that those cuts would be painful, especially for poorer member-states, though limited co-financing for farm payments and more lending for cohesion projects would soften the blow. The structural funds cuts could fall heaviest on the programmes for which wealthy regions are eligible, somewhat sparing the Cohesion Fund, which is aimed at member-states whose GNI is less than 90 per cent of the EU average. The frugal four would not be happy with higher contributions, but their politicians could at least explain to voters that the EU budget was shrinking in absolute terms and doing more to support research, education, and border security. The EU is working with the reality of a rich member-state departing, and something has to give.

Another reality is that a politically divided EU will be unable to agree on new taxes like those explored in the Monti report, and should focus on making the best of the funding streams it already has. The relevant article of the Lisbon treaty stipulates that unanimous support in the Council and ratification in national parliaments is required in order to establish new categories of own resources. In the absence of new funding streams, the percentage of GNI that each member-state pays will simply rise to fund agreed spending priorities not covered by VAT contributions and customs duties.55

Conclusion

The EU faces new challenges and should spend more money on programmes that either tackle the most pressing current concerns of European citizens, such as border security, or will have the most significant long-term effects on Europe’s prospects, such as research, education and student exchanges. Given the departure of the UK, it will not be easy to come up with additional money, but the EU economy is recovering and member-states can afford to cover half of the Brexit gap with additional contributions. Cuts to structural funds and especially the CAP would still mean that the EU budget shrank as a percentage of GNI. New taxes on carbon and on financial transactions would make sense in budget management terms, but it is highly unlikely that member-states will agree to them. Fortunately, the EU can achieve its goals with the current revenue streams if it re-evaluates its spending priorities. With Britain leaving, it is time for incremental progress and greater solidarity from rich member-states, not revolutionary changes.

That is not to say major change is never necessary. The EU will have to monitor continuously how it gets its money and what it spends it on. Perhaps in a less tumultuous period member-states will be willing to pay for ‘more Europe’. Or perhaps it will take another crisis for the remaining 27 to pose the tough questions. Could European taxes on carbon be the best way for Europe to hit its climate targets? Does an ‘ever closer Union’ mean ever stronger central institutions spending significantly more to help poor member-states converge with the rich, particularly within the eurozone? The MFF is only a tiny part of government spending in Europe, but it is also a good barometer of ‘how much Europe’ national politicians really want. Every seven years, member-states ought to put their money where their mouth is.

2: European Commission, ‘EU annual budget life cycle: Figures’, October 2017.

3: European Commission, ‘EU budget 2015 financial report’, January 2016.

4: Agnieszka Lada, ‘Squaring the circle? EU budget negotiations after Brexit – considering CEE perspectives’, Instytut Spraw Publicznych, Warsaw, January 2018.

5: European Court of Auditors, ‘2016 EU audit in brief’, September 28th 2017.

6: European Court of Auditors, ‘Audit brief: Fighting fraud in EU spending’, October 2017.

7: National Audit Office, report by the comptroller and auditor general, July 12th 2017.

8: European Commission, EU expenditure and revenue 2014-20, October 2017.

9: Official Journal of the EU, Council Decision of May 26th 2014 on the system of own resources of the European Union.

10: Alexandre Mathis, ‘”Other Revenue” in the European Union Budget’, European Parliament-Budgetary Affairs, November 2017.

11: Ralf Drachenberg, ‘The European Council and the Multiannual Financial Framework’, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2018.

12: European Commission, ‘A new, modern Multiannual Financial Framework that delivers efficiently on its priorities post-2020’, February 14th 2018.

13: Jörg Haas, Eulalia Rubio, ‘Brexit and the EU budget: Threat or opportunity?’, Jacques Delors Institut, January 16th 2017.

14: European Commission, European and Structural Investment Funds country factsheet: United Kingdom.

15: Matthew Keep, ‘The UK’s contribution to the EU budget’, House of Commons Library, March 23rd 2018.

16: Draft agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union, March 19th 2018.

17: Theresa May, ‘PM speech on our future economic partnership with the European Union’, March 2nd 2018.

18: Egill Elyolfsson, ‘EU Programmes with EEA EFTA Participation’, EFTA.

19: Günther Oettinger, ‘A budget matching our ambitions’, Brussels, January 8th 2018.

20: European Commission, ‘A new, modern Multiannual Financial Framework that delivers efficiently on its priorities post-2020’, February 14th 2018.

21: Alex Barker, EU budget revamp set to shift funds to southern states, Financial Times, April 22nd, 2018.

22: European Commission, ‘The future of food and farming’, November 29th 2017.

23: Mario Monti and others, ‘Future financing of the EU’, December 2016.

24: Jorge Núñez Ferrer, Jacques Le Cacheux, Giacomo Benedetto and Mathieu Saunier, ‘Study on the potential and limitations of reforming the financing of the EU budget’, June 3rd 2016.

25: European Parliament, ‘Post-2020 EU budget reform must match EU’s future ambitions’, February 22nd 2018.

26: Speech by the Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Mark Rutte, at the Bertelsmann Stiftung, Berlin, Feburary 2nd 2018.

27: Jim Brunsden, Mehreen Khan and Alex Barker, ‘”Frugal four band together against Brussels’ plan to boost budget’, Financial Times, February 22nd 2018.

28: ‘Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD‘, February 7th 2018.

29: ‘Merkel will EU-Finanzen reformieren’, Süddeutsche Zeitung, February 22nd 2018.

30: Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska, ‘New deal for the eurozone: Remedy or placebo?’, CER policy brief, November 2017.

31: European Commission, ‘Reflection paper on the future of EU finances’, June 28th 2017.

32: Emmanuel Macron, ‘Initiative pour L’Europe’, Paris, September 26th 2017.

33: Emmanuel Macron, speech on the future of Europe at the European Parliament, Strasbourg, April 17th 2018.

34: Clémentine Forissier, Jean-Sébastien Lefebvre, ‘Budget européen‘, Contexte, January 8th 2018.

35: ‘Agriculture: Ce qu’il faut retenir du discours de Macron’, Ouest-France, January 26th 2018.

36: ‘Joint Statement of the Visegrad Group, Croatia, Romania and Slovenia’, February 2nd 2018.

37: Michael Peel, Mehreen Khan and James Politi, ‘Poland attacks plan to tie EU funds to rule of law’, Financial Times, February 19th 2018.

38: Charles Grant, ‘Macron’s plans for the euro’, CER insight, February 23rd 2018.

39: Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska, ‘New deal for the eurozone: Remedy or placebo?’, CER policy brief, November 2017.

40: European Commission, Standard Eurobarometer 88, November 2017.

41: Camino Mortera-Martinez, ‘Europe’s forgotten refugee cisis’, CER bulletin, issue 114, May 24th 2017.

42: Matthias Parey, Fabian Waldinger, ‘Studying abroad and the effect on international labor market mobility: Evidence from the introduction of Erasmus’, Forschunginstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, April 2008.

43: Mikkel Barslund and Matthias Busse, ‘Labour mobility in the EU, CEPS, July 2016; Eurostat, ‘Half of unemployed young people ready to move for a job’, March 27th 2018.

44: Eurostat, ‘R & D expenditure’, March 2018.

45: European Commission, ‘Horizon 2020 in full swing’, December 2017.

46: Paul-Jasper Dittrich and Phillip Ständer, ‘A European agenda for disruptive innovation‘, Jacque Delors Institut, December 11th 2017.

47: Sophia Besch, ‘What future for the European defence fund?’, CER insight, June 28th 2017.

48: Gregory Claeys and Alvaro Leandro, ‘Assessing the Juncker plan after one year’, Bruegel, May 17th 2016.

49: Eulalia Rubio, ‘The next Multiannual Financial Framework and its flexibility’, European Parliament’s Committee on Budgets, November 2017.

50: Jasna Selih with Ian Bond and Carl Dolan, ‘Can EU funds promote the rule of law in Europe?’, CER policy brief, November 2017.

51: Alessandro D’Alfonso, ‘The UK “rebate” on the EU budget’, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2016.

52: Janosch Delcker, ‘Oettinger wants to scrap all rebates in post-Brexit EU budget’, Politico, January 6th 2018.

53: Alan Matthews, ‘Co-financing CAP Pillar 1 payments’, Capreform.eu, March 27th 2018.

54: Jörg Haas and Eulalia Rubio, ‘Brexit and the EU budget: Threat or opportunity?’, Jacques Delors Institut, January 16th 2017.

55: Article 311 TFEU.

Noah Gordon was the Clara Marina O’Donnell fellow (2017-18) at the Centre for European Reform, April 2018.

View press release