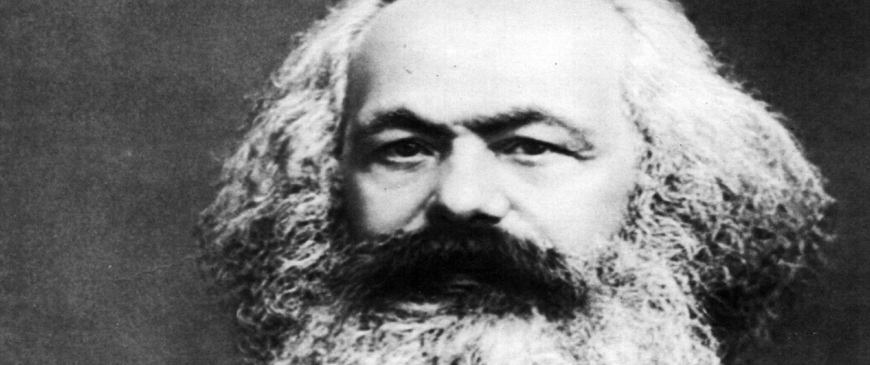

A Marxist take on the 'Brexit' general election

The ideas of Karl Marx suggest that Britain’s general election will not define the country's relationship with the EU.

It is tempting to see the British general election, to be held on May 7th, as a pivotal moment in Britain’s relationship with the EU. If the Conservatives form a government, there will be a referendum on Britain’s EU membership by the end of 2017. If Labour does so, there will not. At the time of writing, the election is impossible to call, with both parties neck and neck in the polls, but neither likely to win enough seats for an outright majority.

Karl Marx’s theory of history should lead us to the opposite conclusion, however: that the election will determine nothing. “The mode of production of material life,” he wrote, “conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life”: economic developments give rise to politics, not the other way round. And economics will determine the politics of Britain’s relationship with the EU.

The underlying problem is the eurozone, but not, as many argue, because it is more dirigiste than the UK. Those who believe that the Continent loves red tape have not noticed that, on average, eurozone member-states’ propensity to regulate their economies is now only slightly stronger than the UK’s, as measured by OECD indicators. The Juncker Commission’s agenda, which seeks to further integrate the supply side of the European economy, could have been written in Westminster (the absence of meaningful services liberalisation aside). Rather, the problem has been the eurozone’s macroeconomic policies since the crisis began in 2008, which derailed Britain’s hopes for an export-led recovery.

The eurozone’s crisis response was this: the periphery would regain competitiveness through falls in real wages by way of a prolonged period of high unemployment. This would not have been too harmful to British exports had the core provided an offsetting boost to eurozone consumption, but the periphery shouldered the burden alone. Monetary policy was kept tight, partly because the European Central Bank forecast that the economy would rebound and partly because quantitative easing was too difficult politically, at least until every other tool had been tried. The result: eurozone demand was so weakened that the value of British exports to the eurozone fell by 11 per cent in real terms from their peak in 2006 to 2013. The UK’s current account deficit ballooned to 4.4 per cent of GDP in 2014, even as British exports to the rest of the world grew quickly. The IMF forecasts the eurozone’s trend rate growth to be 1.6 per cent a year – far lower than the rest of the world. The consequence: Britain will continue the slow process of decoupling from the rest of Europe.

The idea that the opposed interests of capitalists and labour drives social change – and hence politics – was central to Marx’s theory. This is also pertinent to the ‘Brexit’ question. Business is largely in favour of staying in the EU, since investors hate uncertainty and they rightly fret about diminished access to the single market after withdrawal. Meanwhile, people who have less capital, either of the financial or human kind, are more fearful of the greater competition that arises from immigration and international trade.

Immigration from the EU to Britain is likely to remain high in the next few years, as unemployment will only fall slowly in many eurozone countries, and Italian and Spanish workers will continue to move to Britain in search of work. It is almost certain that the UK economy will grow faster than the eurozone, and its flexible labour market is easily capable of absorbing the current rate of immigration from the EU. But British workers are increasingly hostile to immigration, and, despite liberals’ best efforts to convince them that it is beneficial, this will make them more antagonistic to the EU.

Capitalists, on the other hand, see poor prospects for investment in the rest of Europe. While they are unlikely to want the costs of trade and investment with rich countries on Britain’s doorstep to rise, even as Britain’s economic ties with Europe become less important, their enthusiasm for the Union will wane. The current pro-membership coalition of multinational firms, half of the Conservative party, Labour and most of the smaller parties, bar UKIP, will weaken unless the eurozone becomes a faster-growing place. Big business will not become eurosceptic. But as Britain’s decoupling progresses, business will become less willing to forcefully challenge a future Conservative government that favours EU withdrawal.

If the Conservatives lose the election, the price of becoming next Tory leader might be to offer a more radical EU policy than Cameron’s. To win the leadership, candidates might be forced to demand a more drastic renegotiation than Cameron’s moderate set of reforms, or even promise to campaign to leave the EU in a referendum. Conservative party members are more eurosceptic than its MPs, and they get to decide who becomes leader if more than one candidate stands. And when the Conservatives next win a parliamentary majority the pro-European coalition will have been weakened by slow eurozone growth, and continued neurosis about immigration.

There is a glimmer of hope for pro-Europeans. Marx’s great mistake was to fail to consider that governments would establish welfare states, as well as public education, health, and progressive taxation systems to prevent inequality from destroying the capitalist order. So far, in times of crisis, the eurozone’s leaders have done just enough to hold the bloc together. It will probably require another recession to force them to tackle the currency union’s design flaws. And unless the eurozone overcomes its problems, the risk of ‘Brexit’ can only grow.

John Springford is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.