The new EU-Swiss deal: What it means and the lessons it holds for the UK-EU 'reset'

The recent political agreement between the European Commission and the Swiss government promises to stabilise their long-troubled economic relationship. The British government should pay close attention.

Last December, the European Commission and the Swiss government concluded negotiations on a series of agreements aimed at strengthening their economic ties. If ratified, these agreements will place Swiss participation in the EU single market on a firmer footing. But the deal is significant for another reason: in negotiating it, the Commission established clear conditions for granting privileged single-market access to countries outside the European Economic Area (EEA), effectively creating a new model for partial integration into the single market. This offers important lessons for the UK as it seeks a ‘reset’ of its post-Brexit relations with the EU.

The evolution of the EU-Swiss relationship

For the past 30 years, Switzerland has enjoyed access to parts of the single market through a patchwork of over 100 bilateral treaties. This unusual arrangement emerged by accident rather than by design. After rejecting EEA membership in 1992, Switzerland’s relationship with the EU evolved incrementally. New agreements were added, while Swiss law-makers voluntarily adopted parts of EU law in a process often described as ‘autonomous adaptation’. This led to the country’s integration into the EU’s single market in most goods – but not in services – while it remained outside the customs union and operated an independent trade policy. The Swiss also accepted free movement of persons and contributed financially to EU cohesion efforts.

Over time, however, Brussels grew frustrated by Switzerland’s ‘pick-and-choose’ sectoral approach. In the EU’s view, Switzerland benefited from reciprocal market access while retaining too much discretion in applying EU laws, without those laws being supervised and enforced by EU institutions. Brussels’ specific concerns revolved around the absence of a mechanism through which Bern would ‘dynamically’ align with changes in EU law, the lack of enforcement and dispute settlement, and concerns over inconsistencies with case-law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The Commission also lamented the lack of a level ’playing field’ in areas such as state aid. For Swiss policy-makers, maintaining a degree of discretion, particularly for constitutional reasons, was seen as a priority, while they appreciated that if close economic relations were to continue, the EU’s concerns had to be addressed in one way or another.

Over time, Brussels grew frustrated by Switzerland’s ‘pick-and-choose’ sectoral approach.

Both sides made repeated attempts to address these issues. In 2018, after four years of negotiations, they reached an Institutional Framework Agreement (IFA), which sought to create a single ‘institutional roof’ for key bilateral accords. However, the Swiss Federal Council ultimately refused to endorse the agreement, citing domestic political opposition over sovereignty and immigration concerns. The breakdown of talks in 2019 prompted Brussels to apply pressure. Switzerland lost ‘equivalence’ status for its stock exchanges, barring them from serving EU clients, and Swiss participation in EU research programmes was suspended. A period of heightened tensions followed until negotiations resumed in 2023, culminating in a new set of agreements last December – 12 years after both sides first called for a ‘reset’ of their relationship.

Key elements of the new EU-Switzerland deal

The new deal takes a different approach from the IFA concluded in 2018. Rather than establishing a single, all-encompassing framework, negotiators adopted an agreement-by-agreement approach, each with built-in institutional provisions. In some areas, entirely new treaties were concluded; in others, existing agreements were updated. The result is a set of agreements and, as both sides emphasise, a carefully balanced package.

The most significant new treaties cover food safety and electricity trade. A new agreement on food safety will establish a ‘common food safety area’ under which Switzerland will dynamically align with most EU food-safety rules, and participate in the European Food Safety Authority. The second new agreement integrates Switzerland into the EU internal electricity market. Another treaty restores Swiss participation in several EU programmes, including Horizon and Erasmus+.

Several existing treaties will also be modernised. These include the mutual recognition agreement (MRA) covering trade in goods, which will be updated to ensure that Switzerland dynamically aligns with changes in EU product safety rules. The free movement of persons agreement, one of the most controversial parts of the negotiations, is also updated. It includes a redrawn safeguard clause – which can be used to suspend free movement in cases of “serious economic or social problems” and will now be subject to arbitration, providing legal recourse for both sides. This removes the opportunities for punitive actions by the EU if Switzerland were to invoke the clause in the future.

Perhaps the most significant part of the package is the inclusion of new institutional and state-aid provisions. These include a mechanism for Switzerland to dynamically align with EU rules through decisions of the Joint Committee, a body responsible for overseeing relevant agreements; a dispute resolution mechanism that uses an independent arbitration panel, with the ECJ only involved in questions concerning EU law; and a commitment by Switzerland to interpret agreements consistently with ECJ case-law. In a nod to the Swiss concerns about applying EU rules without representation, Switzerland will also be granted a consultative role in the EU’s pre-legislative processes, akin to the ‘decision-shaping’ rights of EEA members.

State-aid provisions have been agreed for agreements on air transport, land transport and electricity trade, requiring Switzerland to implement a new state-aid control system with enforcement equivalent to that of the EU, and monitored by a new independent surveillance authority. Additionally, a permanent mechanism has been established to replace the ad-hoc approach to determining Swiss financial contributions to EU cohesion funds.

The outcome may not be as neat as the EU initially sought. The Swiss relationship will still be governed by a vast patchwork of treaties – many of which will now contain built-in governance provisions. However, key aspects will now be more structured and formalised, which was ultimately the EU’s primary goal. For Bern, the prize is more stable market access and, as the hope goes, fewer future political flashpoints with Brussels.

There are still potential hurdles. The deal needs to be approved by the Swiss parliament, which is unlikely before 2026. One worry is that it could become a focal point of federal elections in 2027 – traditional eurosceptics may oppose the deal on sovereignty grounds, while some on the left worry that the deal might undercut Swiss wages and worker protections. Even if approved politically, the deal will almost certainly face a national referendum and may not come into force for several years.

A new model for partial integration into the single market?

For years, the EU has insisted that countries seeking preferential access to its single market must choose one of two models: full membership of the EEA or a more limited free-trade agreement, with no middle-ground options. This stance was founded upon two key principles. First, the supposed ‘indivisibility’ of the single market meant accepting all four freedoms was necessary for access on equal terms as EU member-states, thus excluding any forms of selective participation. Second, the single market was viewed as more than a rulebook – it is an ‘institutional ecosystem’, where enforcement and oversight by EU institutions preserve its integrity.

For years, the EU has insisted that countries seeking preferential access to its single market must choose one of two models: full membership of the EEA or a more limited free-trade agreement.

This position was always more of a political construct than a reflection of the legal reality. Brussels was content to tolerate ‘cherry-picking’ with Switzerland for over three decades, just as it accepted the exclusion of fisheries and agriculture from the EEA. More recently, in the Windsor Framework, the EU agreed for Northern Ireland to participate selectively – integrating only in the single market for goods, with special conditions governing its external border. Flexibility, it seems, has always been permissible when politically desirable.

The novelty of the Swiss deal is that the Commission has not only acknowledged this flexibility but also decided to formalise it. It now explicitly recognises that institutional guarantees can be provided without direct involvement of supranational EU institutions (or their equivalents in the case of the EEA Agreement), and that selective participation in the single market can indeed be accommodated, even for countries outside the EEA framework. Selective participation, in fact, can be very tailored: within the newly created common food safety area, Switzerland is required to follow most, but not all, EU SPS laws. It can, for example, maintain distinct rules on genetically modified organisms, which are otherwise prohibited within the single market, as well as certain animal welfare standards.

The key consideration, according to the Commission’s updated doctrine, is whether an ‘overall balance of rights and obligations’ is maintained. This phrase, frequently invoked during the Brexit negotiations, served as the guiding principle for Switzerland as well. What constitutes a fair balance of rights and obligations remains, however, a matter of political judgement.

Switzerland’s selective participation in the single market comes at a political cost: continued acceptance of the free movement of people and ongoing financial contributions towards EU cohesion and other such priorities such as tackling migration challenges. There are legal oblgiations, too. These related to institutional safeguards to ensure that EU rules are applied, interpreted and enforced consistently in areas where Switzerland participates. Here, the Commission’s doctrine has evolved. Previously, the Commission insisted that only EU institutions could reliably safeguard the integrity of the single market: new EU laws would have to be adopted ‘dynamically’ with little scope for carve-outs; the Commission required enforcement powers, including through infringement proceedings before the ECJ; the ECJ needed involvement identical to that for member-states; and states could face penalties for non-compliance.

Switzerland’s selective participation in the single market comes at a political cost: continued acceptance of the free movement of people and ongoing financial contributions.

The adjustments in these positions are nuanced but significant. The Commission still insists on dynamic alignment with EU legislation, but it now accepts this can be implemented through Joint Committee decisions, allowing some scope for political negotiation regarding entirely new EU rules. The Commission has also consented to independent arbitration for dispute settlement, keeping the ECJ at arm’s length and limiting its role to providing interpretations on questions of EU law rather than ruling on the dispute in its entirety. Additionally, it also accepts that non-compliance measures, when necessary, should be “proportionate” and localised to the single-market related areas rather than applying broad punitive actions.

Through the Swiss agreement, the Commission has effectively defined the conditions under which a country might participate in parts of the single market without full EEA membership. Whether the EU would extend similar flexibility to other countries remains uncertain. Nonetheless, the Swiss deal illustrates that the EU can adopt an imaginative and flexible approach when its core interests are safeguarded and there is a clear political incentive to reach a deal.

Lessons for the UK’s ‘reset’ with the EU

During the Brexit negotiations, any mention of the “Swiss model was swiftly dismissed by EU officials as unworkable and unrealistic. The reasons were simple: the relationship with Switzerland was seen as a complex mess, and Brussels was in the middle of restructuring it.

Yet, in reality, the parallels between the Swiss and UK negotiations were greater than publicly acknowledged. Both talks revolved around a central question about how to apply, interpret and enforce provisions of EU law in a non-EEA country. It was no coincidence that the same EU negotiating team handled both talks, careful to ensure that precedents set in one negotiation would not complicate the other. Nor was there any surprise when the institutional provisions in the UK Withdrawal Agreement closely mirrored those in the 2018 IFA, even as the two negotiations concluded within weeks of each other.

The parallels between the Swiss and UK negotiations were greater than publicly acknowledged. Both talks revolved around a central question about how to apply, interpret and enforce provisions of EU law in a non-EEA country.

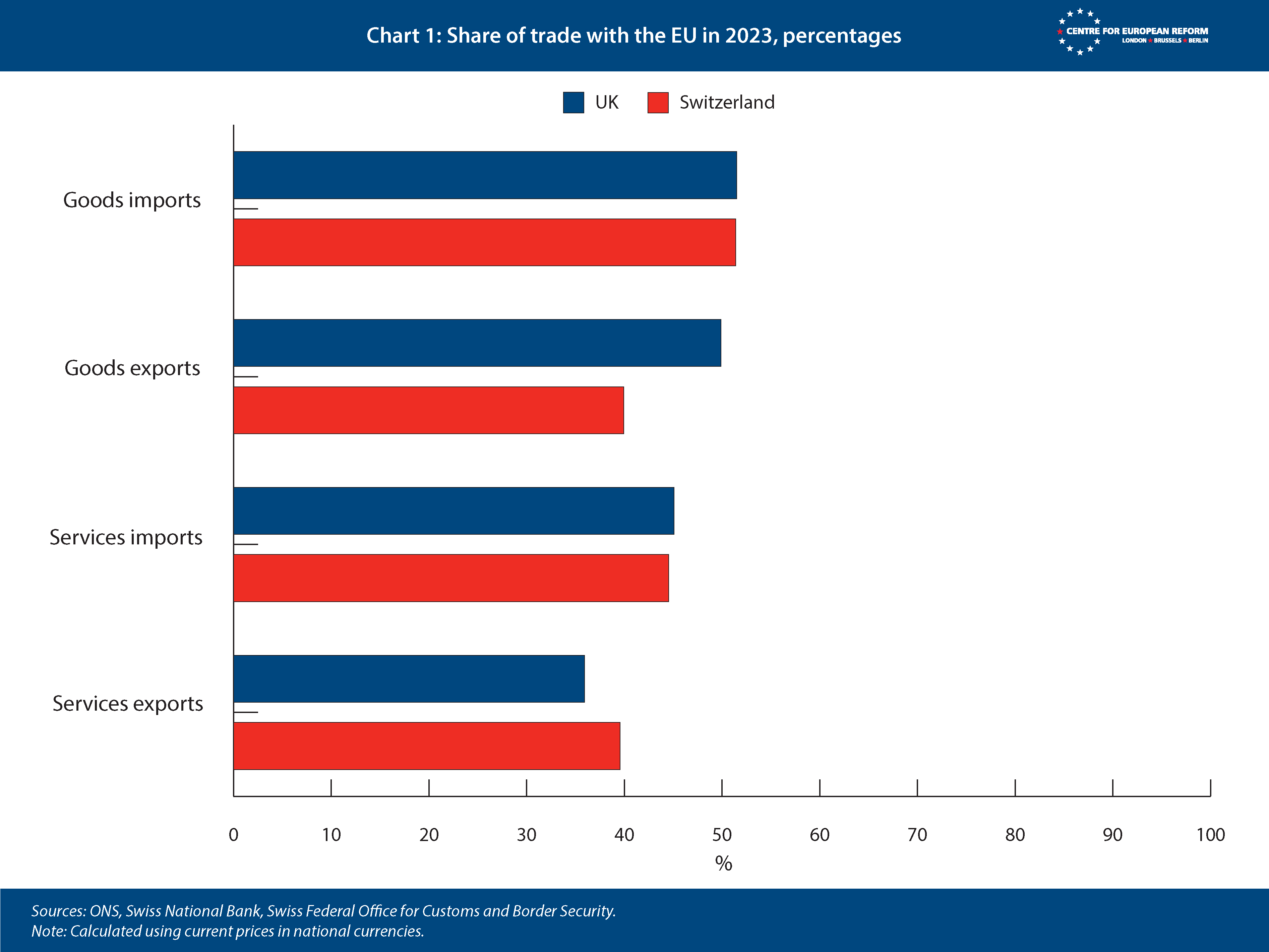

Broader similarities also exist. Britain’s and Switzerland’s economies share a similar trade profile with the EU (Chart 1). Both are heavily integrated in the single market for goods but have greater global exposure in services; have large financial sectors and value regulatory autonomy despite some market access costs; and have electorates sensitive to sovereignty concerns.

Although the Labour government has ruled out rejoining the single market, the Swiss agreements offer useful lessons for the UK. Three aspects are particularly relevant for its planned EU reset.

Although the Labour government has ruled out rejoining the single market, the Swiss agreements offer useful lessons for the UK.

First, the creation of a common food safety area sets a precedent for any efforts to agree a UK-EU veterinary deal. If Labour ministers seek the removal of most physical border checks and paperwork required for EU-destined food products, the Commission is likely to point to this agreement and insist on dynamic alignment. Alternative approaches, such as equivalence, would likely be deemed insufficient.

Second, the new agreement on electricity could provide some ideas for closer integration between Great Britain and the EU’s internal electricity market. Electricity trading remains unresolved under the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), despite efforts from both sides. The European and British energy industries have jointly called for the reintroduction of ‘price coupling’, which is at the core of the EU’s integrated electricity market. The Commission has recently pushed back on such suggestions, but the flexibility granted to Switzerland suggests that a more bespoke approach is not inconceivable.

The British government should also look closely at the updated MRA, which could offer a more streamlined approach to certifying product safety for manufactured goods. The EU previously rejected the UK’s attempts to secure such an arrangement, but the UK’s Product Regulation and Metrology legislation – which would offer a route to voluntary alignment with EU product safety rules – could make a MRA more viable.

A broader question is whether the Swiss agreements offer a ‘model’ for a more ambitious reset of the UK-EU relationship. Could this approach offer a route back into the single market for goods only, while preserving autonomy in services and an independent trade policy? Could it enable more constructive discussions about integrating the UK into the EU’s emerging defence-industrial cooperation, anchored in single market principles, even as an external partner? Could it, in short, shift the conversation from the default ‘pas possible’ to exploring the conditions necessary to make closer relations achievable?

Could the Swiss agreements offer a ‘model’ for a more ambitious reset of the UK-EU relationship.

This question merits serious consideration at the highest levels of administrations in Brussels and London. For a UK government seeking to revive sluggish economic growth, the economic case for substantially easier market access with its largest trading partner is compelling; for the European Commission, keeping London closer to Brussels than to Washington makes a strategic sense. Most importantly, for collective European security in a world where the US no longer provides a security guarantee, incorporating the UK, as a significant defence actor, under a common European defence framework seems both logical and necessary.

What is clear is that privileged market access wouldn’t be cost-free. The UK will have to accept some institutional obligations, and some financial contributions would likely be required, though these could be directed towards mutual priorities such as funding Ukraine’s security or reconstruction. More contentious is the issue of free movement. This remains sensitive for most British politicians, including Labour strategists wary of voter defections to Reform UK before the next election. Switzerland accepts free movement with an emergency break – an approach not dissimilar to the deal David Cameron negotiated before the Brexit referendum. Still, persuading the British public would require real political skill.

Ultimately, the Swiss deal demonstrates that the EU can be creative and flexible when there is a shared destination, trust and political incentives that align. The challenge for the British government is demonstrating that it has a desired destination in mind and, more importantly, something meaningful to offer in return. Without that, there is a risk that the UK’s reset will be little more than a symbolic exercise.

Anton Spisak is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment