Trump's Iran policy leaves the EU few options

Trump’s decision to re-impose sanctions has placed the Iran nuclear agreement on life support and further destabilised the region. Unwilling to seriously support the deal, Europeans will have to rely on diplomacy to limit the damage.

On November 5th, the US re-imposed sanctions on Iranian oil, banking and shipping. The sanctions followed US president Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), in May. Trump urged Iran to “abandon its nuclear ambitions, change its destructive behaviour, respect the rights of its people, and return in good faith to the negotiating table.”

The US has made clear that it will oppose any attempt to keep the JCPOA alive.

To avoid a spike in the oil price, the US granted waivers to enable China, India, Italy, Greece, Japan, South Korea, Turkey and Taiwan to continue importing Iranian oil temporarily. These waivers are only supposed to last 180 days, with beneficiaries gradually reducing their purchases. Moreover, the revenue generated by these purchases will be placed in foreign accounts, which Iran can only access to buy non-sanctioned goods such as food and medicine.

The move was welcomed by some of the US’s regional allies: Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Israel. Europeans greeted Trump’s decision with disappointment. The UK, France, Germany and the EU issued a statement pledging to uphold the deal with Iran. Since Trump’s decision to withdraw from the agreement, Europeans have sought to convince Iran to preserve it, by ensuring that European companies could continue doing business with Tehran despite US sanctions. In theory, the EU could mobilise its economic heft to keep the deal alive. For example, it could set up a mechanism to indemnify European businesses for the costs of US sanctions or try to sustain Iranian oil purchases.

In early June, the European Commission adopted an update of the EU’s Blocking Statute. Introduced in 1996, following the adoption of new US sanctions on Cuba, Iran and Libya, the statute prohibits EU-based companies from complying with US extraterritorial sanctions. But the measure has proved to be toothless: firms are more fearful of US sanctions than of the statute. European businesses, from aircraft manufacturer Airbus to oil giant Total, have pulled out of Iran. The costs of US sanctions can be very high: in 2015 the US fined BNP Paribas $8.9 billion for violating sanctions on Iran, Sudan and Cuba. Firms with exposure to the US market will always prioritise it over their relatively small investments in Iran.

Additionally, the Blocking Statute is hard to enforce, as it is difficult to prove that a company has ceased to do business in Iran out of fear of US sanctions, instead of another reason. For example, following the November re-imposition of US sanctions, SWIFT – the Belgium-based financial information service, which underpins international bank transfers – stated it would cut off Iranian banks from its systems. While the decision was clearly motivated by the sanctions, SWIFT cited concerns about broader financial stability, although the company’s chief executive later said it was regrettable that the company was not being allowed to be “neutral”.

Other European plans to preserve some of the financial benefits of the Iran nuclear deal are also stalling. The extension of the European Investment Bank’s mandate to allow it to lend to Iran is flawed, as the bank needs to access international capital markets to raise funds, which exposes it to US sanctions. Europeans are, moreover, finalising a special purpose vehicle to clear payments of Iranian oil. As no single member-state is willing to host the vehicle for fear of retaliation by the US, France and Germany may now jointly host the mechanism to diffuse responsibility. However, reports suggests that the mechanism may not cover oil after all but be limited to less sensitive goods such as food and humanitarian products. While this would alleviate the suffering of ordinary Iranians, it would represent a substantial climb-down from earlier ambitions.

While many European politicians, such as President Emmanuel Macron, argue that Europe needs to affirm its independence from the US, in practice they are unwilling to jeopardise the transatlantic relationship by taking serious steps to sustain business with Iran.

The fear of US retaliation is a powerful disincentive. The US has made clear that it will oppose any attempt to keep the JCPOA alive. Iran-related sanctions on EU firms could become entangled with the tariffs Trump is imposing on European cars, escalating the incipient trade war. It is likely that Trump would attempt to peel off wavering member-states such as Italy, Austria, Greece, Poland, Hungary and the Baltic states. It is also possible that Trump could even threaten to withdraw American troops from member-states that are reliant on the US for deterrence against Russia, such as the Baltic states and Poland.

Europe may also judge that Iran’s broader foreign policy is so hostile to its interests that it is not worthwhile to attempt to preserve the financial benefits of the deal. First, Iran’s destabilising role in the Middle East has long been a source of concern, especially its support for Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon, and its involvement in the war in Yemen. Second, in early December Iran carried out a medium range missile test. The US called the test a violation of UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which “calls upon” Iran not to test nuclear-capable missiles. France and the UK also argued the test may be a breach of the resolution. Third, some member-states are concerned about a series of attacks allegedly plotted by Iranian agents against dissidents in France and Denmark. At a time of increasing concern about state-sponsored assassinations in Europe, concern about Iran’s activities makes it even less likely that member-states will be willing to add to their differences with the US for the sake of Iran. This was underscored by Federica Mogherini’s remark at the latest Foreign Affairs Council that the EU’s support for the deal does not mean it will turn a blind eye to other issues.

Europe’s unwillingness to protect the JCPOA will exacerbate the effects of Trump’s decision to pull out of the deal.

Europe’s unwillingness to protect the JCPOA will exacerbate the effects of Trump’s decision to pull out of the deal. But the impact of Trump’s move will depend on exactly how much pressure the US decides to apply on Iran. The waivers are supposed to be a one-off. But there are different views within the administration about what the end goal of US policy should be. While Trump claims he wants to bring Iran back to the table, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and National Security Advisor John Bolton have placed less emphasis on renegotiating the agreement, listing it only as one of many aims the US is pursuing. There is little doubt that many in the US administration would relish more confrontation, and view sanctions as a means to weaken the regime. It is also possible that the US calculates that its interests are better served by allowing Iran to keep selling enough oil so its economy stays on life support, slowly increasing pressure while minimising the chances of Tehran retaliating by attacking US forces in the region or restarting its nuclear programme.

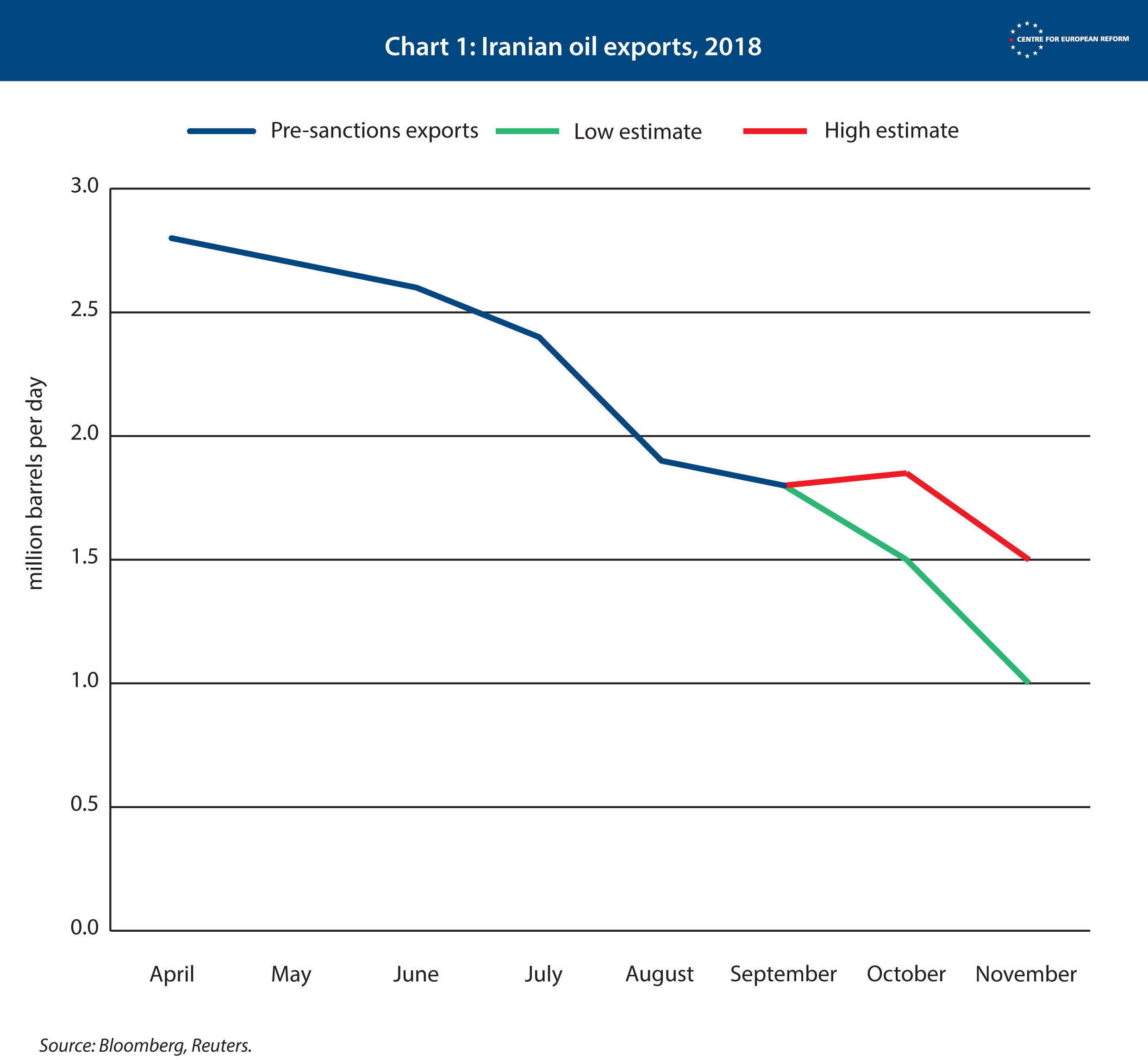

For now, Iran is unlikely to openly violate the original nuclear deal, simply because doing so would greatly increase the chances that the EU, and perhaps also Russia and China, would re-impose sanctions. The key question is what happens if the US sanctions bite hard. The Iranian leadership sold the JCPOA to the Iranian people with the promise that it would bring great economic benefits. These have failed to materialise, and the Iranian economy is already deteriorating as a result of the American sanctions and a broader economic crisis. Iran’s currency, the rial, has already lost 70 per cent of its value against the dollar this year. The International Monetary Fund predicts that Iran’s economy will decline by 1.5 per cent this year and 3.6 per cent next year, when inflation will hit 34 per cent. Oil exports have fallen from 2.8 million barrels per day in April, just before Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the JCPOA, to 1.8 million in September (See Chart 1). Estimates for October vary between 1.5 and 1.85 million barrels a day, and between 1 and 1.5 million in November. Exports are becoming harder to track as Iranian vessels switch off their transponders to avoid being detected. A key question is whether China and India, the main purchasers of Iranian oil, will significantly reduce their purchases.

Faced with mounting internal dissent and unwilling to bow to US demands, the Iranian leadership may calculate that more confrontation with the US is the best way to build leverage and shore up domestic support. As time passes, it is likely that Tehran will test the margins of the nuclear deal. It may for example stockpile centrifuge components, a move which would reduce the time needed to develop a nuclear weapon if it decided to do so. Iran could also use its proxies to attack American forces across the Middle East, or step up its missile tests to gain leverage on the US. Recently, Tehran has also threatened to cut off oil sales from the Gulf. The risk of miscalculation is high and further provocations are likely to prompt the US to escalate in turn.

As time passes, it is likely that Tehran will test the margins of the nuclear deal.

If the EU is serious about maximising the chances to preserve what is left of the JCPOA, and increasing its ‘strategic autonomy’, then it needs to find a mechanism to allow its companies to bypass US sanctions and do business with Iran. Even though the effects may be small, this would send a powerful signal. And, the next time a transatlantic disagreement surfaces, the EU would have the option of using a system that would allow it to mitigate the impact of US sanctions.

However, there is little evidence that Europeans are prepared to incur the high risk of American retaliation, which could expose rifts within Europe itself and lead to a humiliating climb-down. As long as Europe remains unwilling to create such a mechanism, Europeans will have to focus their efforts on strengthening the JCPOA to bring the US back on board. This will not be easy. No matter how much pressure it is under, Iran is unlikely to make concessions as long as it seems possible that Trump may be voted out in 2020. The likeliest scenario then, is that substantive negotiations on how to constrain Iran’s nuclear ambitions will not restart until after 2020, whether Trump remains president or not. Only then will it be possible to revive serious talks, and construct a stronger agreement that goes beyond the JCPOA to address outstanding issues such as the long-term future of Iran’s nuclear program.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment