No, Spain is not 'different': It too needs a grand coalition

With the rising of new parties, Spain’s two-party system has collapsed. But the surge of Catalan nationalism requires an agreement between all political forces to secure constitutional reform.

In 1960, Spanish tourism minister Manuel Fraga launched a campaign to encourage people to visit the country. Memories of the bloody civil war were fresh, and Spain had languished under the leadership of Francisco Franco. Fraga tried to portray Spain as no better or worse than any other country: it was just 'different'. Then from 1975 Spain shifted from dictatorship to a two-party democratic system, following the French and British models. While recent European politics has evolved into a trend of fragmented parliaments and coalitions, Spain has remained stubbornly attached to its two-party system. Spain kept on being 'different', in its own way. But that is no longer the case: after last month's elections, which provided no outright majority for either the centre-right Partido Popular (PP) or the socialists (PSOE), Spaniards will need to get used to pacts. With the rise of Catalan nationalism, a grand coalition is now needed to deal with Spain’s increasingly fragmented politics. Its first priority should be constitutional reform.

With the rise of #Catalan nationalism,Spain needs a grand coalition to secure constitutional reform

In many European countries, two-party systems have given way to more diverse political environments, for better or for worse. Think of France’s National Front, on the rise since 1982 and which came second in the country’s 2002 presidential election. Or of the (previously inconceivable) coalition government that ruled the UK between 2010 and 2015. Coalition governments hold power in Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal, to name a few. Federal countries and as well as those with strong regional identities, such as Germany or Belgium, are usually also ruled by coalitions that ensure a broad representation of interests. In fact, there are now few countries in Europe where strong two-party systems endure.

Spaniards dislike fragmented parliaments, which they feel were the cause of Spain’s political instability during the 19th and 20th centuries. The Spanish electoral law is designed to ensure that the country remains governable while safeguarding the representation of regional minorities. For that, it uses a complex mathematical formula originating in Belgium, the D’Hont system, which benefits big, national parties and those with a strong concentration of votes in particular regions. That is the reason why, until last month’s elections, the Spanish parliament was made up of two large delegations – the PSOE and the PP – and a handful of regional parties, mainly from Catalonia, the Basque Country, Galicia and the Canary Islands.

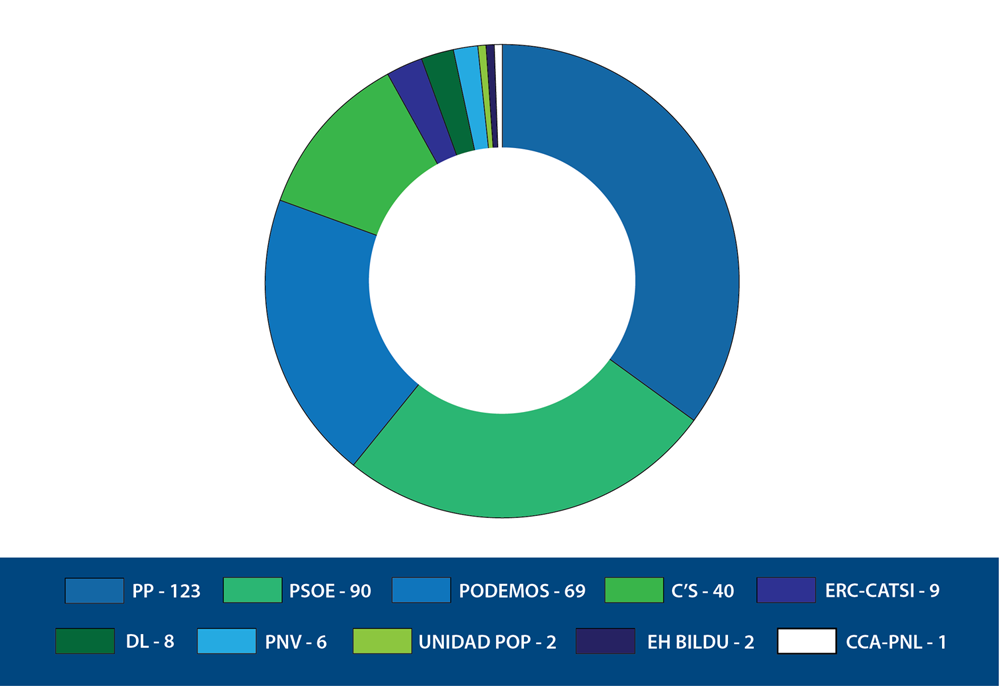

Spaniards may be scared of the political unknown. But they are also tired of the inability of their politicians to put an end to the country’s economic problems, and wary of the stream of corruption cases tainting both PP and PSOE. It was only a matter of time before new parties emerged and gathered popular support. Two of these new parties, Podemos 'We can'– and Ciudadanos – 'Citizens', now hold the balance of power (see chart below).

Negotiations to form a government are continuing, but an agreement will be difficult: apart from Ciudadanos, Mariano Rajoy’s PP does not have another natural ally in parliament, which is needed to form a government. The same is true of the left: the PSOE and Podemos do not have the necessary majority to govern in coalition. And, even if they did, they differ on how to deal with the Catalan question, which would probably make such a pact impossible. The PSOE opposes a Catalan referendum, whereas Podemos would in principle be in favour.

2 new parties, Podemos - ‘We can’ - & Ciudadanos - ‘Citizens’, now hold the balance of power #Spain

The situation in Catalonia dominates much of the Spanish political debate: a coalition would be easier to form were it not for the new Catalonian government, which took office in January 2016 and has threatened to pursue independence unilaterally. The Catalan government has announced that it will disregard decisions by Spain’s constitutional court should they need to do so to obtain independence. The situation is worrying enough, but it is even more so in the absence of a national government. Catalonia could become a serious crisis if Spain does not find a stable coalition to challenge pro-independence forces in the region.

Until now, a German-style grand coalition between the PP and the PSOE would have been unthinkable. They are seen as an ‘either or’ option and there has been little co-operation between the two parties (with the notable exception of bipartisan pacts against terrorism). A grand coalition would probably be worse for the PSOE than for the PP: in Spain, the left is much more fragmented than the right. Principled PSOE voters would not forgive their party for supporting its arch enemy and could easily turn to the rising Podemos. But a grand coalition, perhaps with the support of Ciudadanos, may now be inevitable: if there is no agreement to appoint a prime minister by the end of March, the king would need to call for fresh elections. It is unclear whether these would help to overcome the current political impasse, or whether they would make the parliament more fragmented. In the meantime, the Catalan independence process would be in full motion. So, the PP and the PSOE may have no other option than to form a coalition.

Spaniards – and their politicians – should not forget that their cherished post-Franco democratic transition only worked because of a consensus among all mainstream political forces. Great concessions were made and compromises struck; it may now be time to do the same. The Catalan question is no longer about the right to hold a referendum. It is about whether a regional government is prepared to disobey the law and challenge Spanish courts. This is a serious threat and should be used as an opportunity to rally all major political forces around constitutional reform.

Spain shouldn't forget that the postFranco democratic transition only worked because of a consensus

Spain has long been in need of a new constitution, to address not only the problems associated with rising nationalism, but also to modernise the country’s institutional structure. A grand coalition could make long-lasting reforms. Spain’s quasi-federal model, based on an asymmetric devolution of powers is no longer working: for example, the Basque country enjoys fiscal autonomy whereas Castille does not. A grand coalition could turn the Spanish regional model into a federal system, with a clear-cut and symmetric devolution of powers, based upon a principled, national debate about what powers should be held at the regional level and why. While pro-independence Catalans might not be satisfied, a more logical devolved system would help to dampen independence movements elsewhere in Spain. The Senate should be turned into a proper chamber of regional representation – it was originally designed to play that role, but in reality it has no power. This would be in line with the three parties’ electoral programmes, although it would obviously require compromises, particularly from the PP.

Because a grand coalition would be worse for the PSOE than for the PP, the latter should be prepared to make some concessions. The first one should be to replace Mariano Rajoy: his poor management of the Catalonian question led Artur Mas’ government to start the independence process unilaterally. Rajoy’s role in a scheme to provide illegal funds to the PP has never been clarified. His vice-president, Soraya Saenz de Santamaria, could be a good replacement: she is young, did not rise through the party machine and is popular among Spanish citizens. The PP should also agree to drop some of its austerity measures, and ensure that that Spain’s slow economic recovery reaches every layer of society, and not only the wealthy. The agreement to have a socialist presiding over the Spanish parliament, reached this week, is a step in the right direction.

Of course, coalitions are not always effective: they increase the chances of a government collapsing and sometimes even lead to the near demise of one of the partners (as happened to Britain’s Liberal Democrats in the 2015 general election). There is also a risk that a grand coalition between the establishment parties would alienate voters even more, leading to greater support for radicals. All these are fair considerations that the leaders of the PP, the PSOE and Ciudadanos should take into account when negotiating a new government. But the belligerence of Catalonia’s new government has left no option but to find an agreement, as quickly as possible. New elections may lead to even more deadlock. And Podemos, who started off as an interesting alternative to the establishment, seems now to be increasingly confused, without a clear strategy on either the Catalan problem, or the economic recovery. With bizarre political manoeuvres, such as running under different brands in different regions, Podemos has excluded itself as a serious partner in the negotiations to form a government.

Spain may have been different 50 years ago. But it is now a full-fledged member of the European Union, with a market economy and a democratic political system. Spanish politicians need to make the transition to 21st century politics: they should trust their young democracy to be resilient, and opposing parties to be capable of compromise. Without a grand coalition willing to make concessions in the national interest, Spain may break up.

Camino Mortera-Martinez is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.