Moving back the finishing line: The EU's progress on climate

European leaders’ aim to go carbon neutral by 2050 will not happen without much tougher emissions curbs by 2030, and a sizeable increase in research and development funding.

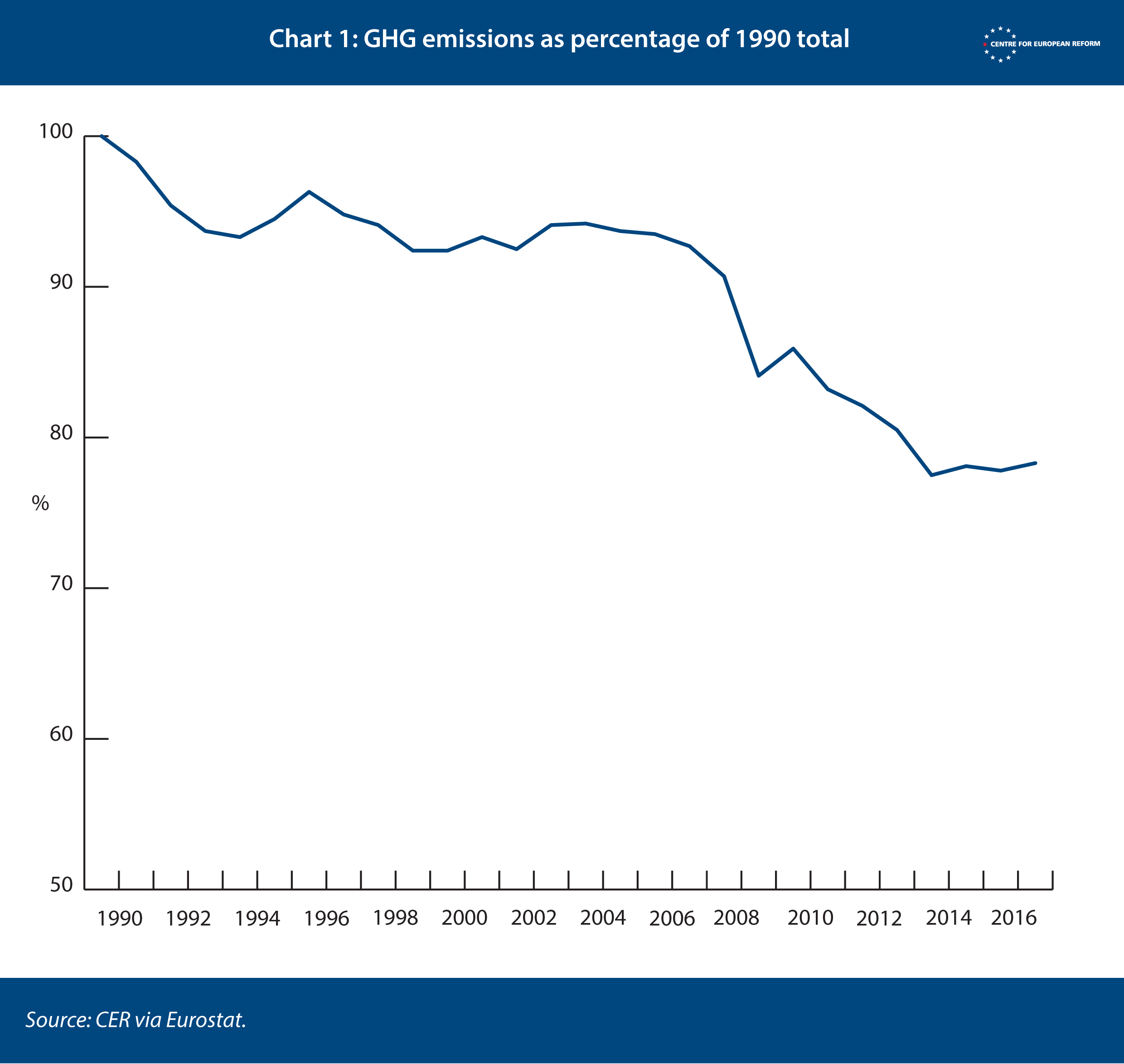

Climate change has moved to the top of the European political agenda, as the reality has started to sink in: rising sea levels, more frequent heat waves, droughts, floods and forest fires, increased water scarcity, reduced agricultural productivity in Southern Europe, more forced migration, and the extinction of species. The EU is projected to achieve its 2030 emissions targets, which it made in 2015 in its submission to the Paris climate agreement: a 40 per cent reduction in emissions from their level in 1990. (As of 2017, emissions were down by 22 per cent from 1990 levels – see Chart 1.)

The EU has done much better than most other industrialised countries. US emissions have risen slightly since 1990, and global emissions continue to rise.

The EU has done much better than most other industrialised countries. US emissions have risen slightly since 1990, and global emissions continue to rise. Over the next few months, starting at today’s climate conference at the UN in New York, signatories to the Paris agreement will update their targets in light of the latest climate science. Under the 2015 UN Paris Agreement, countries do not commit to temperature targets. Instead they commit to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an amount meant to be sufficient for the planet to reach its temperature target. And in order to keep global warming well below 2 degrees, which climate scientists believe is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, the EU must significantly raise its 2030 target for emissions curbs.

The Commission has said the target will be met if current EU-level policies “are fully implemented”. A European Commission analysis from November 2018, which quantified the extent to which already agreed EU policies would curb emissions, said greenhouse gas emissions would fall by 46 per cent from 1990 levels by 2030. A March 2019 study from the climate think-tank Sandbag, which took into account not only EU policies but also recently announced national coal phase-outs, forecasts a 50 per cent reduction. While there is always the potential for member-states to struggle with implementation, given political trends and advances in green technology, it would be surprising if the EU failed to hit its 40 per cent target.

It is clear that the EU’s current target of a 40 per cent reduction by 2030 is not sufficient. The UN Emissions Gap Report of November 2018 said that even if every country achieved the emissions reductions it had committed to at that time, the world would still warm up by about three degrees by 2100. European politicians acknowledge more work is required. Before proposing what that target should be, this note discusses the action that the EU has taken in recent years, and the EU’s policy framework for delivering that target. The EU’s recent progress shows that a much tougher target is achievable.

It is clear that the EU’s current target of a 40 per cent reduction by 2030 is not sufficient.

Before 2018, the EU was on track to fall short of its 2030 goals. The European Environment Agency ran projections based on member-state policies as they stood in March 2017 and found that emissions would only decrease by 30 per cent by 2030 compared to the 1990 baseline.

Then the EU carried out three major reforms. First, it reformed the Emissions Trading System (ETS). The ETS is the EU’s cap-and-trade system that sets a limit on the amount of greenhouse gas pollution that can be emitted each year by energy, industrial or aviation companies. If firms do not have enough permits, they must buy them from other companies that are polluting less than their permits allow. The annual amount of emission allowances, which decreases every year, will be reduced faster from 2021. This means there will be both fewer allowances available to purchase and fewer allowances given away for free to industries exposed to carbon ‘leakage’ – the transfer of production to other countries with laxer emission restraints.

The 2008-2009 financial crisis and the subsequent euro crisis had led to an over-supply of ETS allowances and thus a collapse in prices: from 2012 to 2017, it cost an average of €7 to emit a ton of carbon dioxide, a price too low to put serious financial pressure on, for instance, coal-fired power plants. The UK took matters into its own hands in 2013 and established a carbon price floor of £16 per ton. The EU’s response was to postpone the auctions of allowances from 2014-2016 until 2019-2020, and to create a reserve for allowances if circulation rises above a certain threshold, so that the market was not flooded with yet more permits.

These steps have had an effect on costs companies incur if they pollute. In the summer of 2019, the price of an allowance hovered around €25 per ton. At this level the ETS creates some additional costs for European industry, not only directly but also through higher electricity prices, and prices are bound to rise. Industry groups are warming to the idea of a border adjustment tax to protect firms from high-carbon foreign competition.

Second, the EU updated its Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), which covers sectors outside the scope of the ETS, such as transport, buildings, agriculture, and waste. The May 2018 regulation sets an EU-wide target of a 30 per cent reduction by 2030 (compared to 2005), but it establishes different emissions limits for different member-states, taking into account their level of economic development and current energy supply mix. In this regard, Sweden should reduce emissions by 40 per cent and France by 37 per cent, whereas Poland should reduce them by just 7 per cent and Bulgaria not at all.

The ESR is a flexible regulation, allowing member-states to buy and sell ESR allowances to one another, as firms can do with ETS allowances. The goal is to encourage the most cost-effective reductions in emissions. Nevertheless, the regulation has teeth. Laggards can face Commission infringement proceedings and have their emission allowances reduced, and it can get expensive for countries to buy their way out of trouble: Germany, which is behind in this area, is projected to have to spend €30-60 billion on allowances in the period 2021-2030.

Third, Brussels set more ambitious targets for renewables and energy efficiency. Renewables should make up 32 per cent of final energy consumption by 2030, while energy consumption should be 32.5 per cent less in 2030 than it was projected to be in 2007. Those targets are part of what the EU calls the ‘clean energy package’. The package includes EU-level legislation, like setting standards for biofuels. The EU has also taken more direct regulatory action in other climate areas, like the new fuel efficiency standards for cars it passed in April of this year. Member-states have until May 2020 to transpose the EU legislation into national law, but the detailed plans to hit the targets are up to them. Member-states must submit, by the end of 2019, their final National Energy and Climate Plans for the period 2021-2030.

Thus the EU’s institutions have proved able to set binding targets for member-states to achieve, and to take some direct policy action through the ETS and ESR. But the difficult work of implementing the targets is left to the member-states – and here is where some problems have arisen.

The EU’s member-states submitted draft versions of their national climate plans in December 2018, detailing their own targets, policies, data, and projections. According to the Commission’s assessment, progress so far is a mixed bag. Under current draft plans, the EU would fall just short of having 32 per cent of its energy come from renewables in 2030. The picture is less rosy for the 32.5 per cent energy efficiency target, where the EU is on track to attain a reduction between 26-30 per cent. The Commission has said the plans “represent significant efforts” but “require a collective step up of ambition”.

However, these plans are provisional, and one would expect member-states to get greener over the next few months and indeed the next 11 years. For instance, when it submitted its report, Germany had not yet set a date for its coal phase-out; the country has since announced that it will shut some coal plants by 2022 and all of them by the very late date of 2038. On Friday, it added its long-awaited ‘climate package’. Nevertheless, national policy is not yet enough to hit these current EU-level renewables and efficiency targets before they are revised upwards again in 2023.

The Commission’s drive to “step up ambition” also reflects the increased environmental debates and protests going on at the national level.

The Commission’s drive to “step up ambition” also reflects the increased environmental debates and protests going on at the national level. The gilets jaunes grabbed the headlines, but the French Greens, like their German counterparts, also achieved a record result in the 2019 European Elections, while the Fridays for Future school strike movement has shaken up youth politics across the continent. Poland, meanwhile, continues to build new coal-fired power plants. The outcome of these debates will determine whether and when EU climate legislation is “fully implemented”, setting the EU up to hit this target and the next.

So what about that next Paris target for reductions by 2030, which are due by 2020? The Paris signatories set themselves moving targets. The first goals were submitted in 2015 and subsequent ones are due by 2020, 2025, and 2030. At each of those points, countries have to submit new targets which ‘ratchet up’. Previous ones were insufficient to achieve global warming of “well below 2 degrees".

It would be senseless to keep it below the 45 per cent the EU already expects to achieve. In March, the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for a 55 per cent target, a demand echoed by UN President Antonio Guterres.

Yet in recent months there has been more attention on what the EU should do by 2050 than by 2030. A group of Western and Nordic nations including France, Denmark, The Netherlands, Spain, and Germany has been pushing for a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, though it failed at a Brussels summit on June 17th, when the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, and Poland blocked a deal because of their concerns about social unrest and the size of the compensation package they would receive. By conducting a debate about 2050 targets, the EU is tacitly pushing the political costs of climate action into the future, to be dealt with by a future generation of politicians. Action is needed now for the EU to have a realistic path to net zero by mid-century.

In a recent study, the European Climate Foundation, alongside dozens of European universities and research institutions, found that in order to “be on a trajectory to net-zero by 2050, GHG emissions will need to be reduced from about 55–65 per cent compared to 1990 levels” by 2030. Infrastructure investment takes a long time to plan and construct, and new electricity plants will be in use for decades. And decarbonising the electricity sector is comparatively easy compared to transport and buildings. Thus, the EU should set its sights higher and change its Paris Agreement goal to a 60 per cent reduction on 1990 levels by 2030.

The European economy needs price signals today to stop greenhouse gases accumulating and prevent firms from making carbon-intensive investments, and it needs to look ahead to a period when the relatively low-hanging fruit is gone too. The EU’s next long-term budget for 2021-2027, which will be agreed in early 2020, must include a sizeable increase in expenditure on low-carbon infrastructure and research and development (R&D) into zero-carbon technology. Member-states will also have to raise national R&D spending too. Such research is required to eliminate the most stubborn emissions, such as the carbon emitted during cement and chemical production.

Given the low cost of borrowing on financial markets, European governments are too timid about taking on debt to help the leaders of 2040 meet their targets. Those future leaders will be just as constrained by political conditions as are their current counterparts. Future prime ministers are unlikely to resent their 2019 predecessors for having sold more bonds to finance, say, bigger subsidies for industry R&D or the modernization of electric grids to support the expansion of wind power.

Given the low cost of borrowing on financial markets, European governments are too timid about taking on debt to help the leaders of 2040 meet their target

Some signatories to the Paris accord will update their targets in New York today; others will wait until the 25th UN Climate Change Conference in Chile in December. The EU can wait a few extra weeks to decide after the von der Leyen Commission takes office on November 1st, but it must set a target that is high enough to avert the worst effects of climate change. Otherwise, it will be missing both the forest and the trees.

Noah Gordon is the climate editor at Berlin Policy Journal and a former Clara Marina O’Donnell Fellow at the CER.

Add new comment