The G7 corporate tax deal: Why the EU should curb its enthusiasm

The recent G7 deal will not bolster the European Commission’s broader efforts to fight aggressive tax practices. The Commission needs political realism and more modest aims to make headway.

International tax does not get more exciting. The European Commission has spent many years trying to tackle some EU member-states’ tolerance for aggressive tax practices: the Commission recently cited evidence that Europe loses between €35-70 billion in corporate tax avoidance each year and that 80 per cent of profits shifted in the EU are moved to EU-based tax havens, like Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. The Commission’s past attempts to address avoidance have been repeatedly thwarted by the need for unanimity among member-states on tax decisions. But times are changing. The G7, a group of large countries with developed economies, now supports a global minimum corporate tax rate; and some previously obstructionist EU member-states, like the Netherlands and Luxembourg, are rethinking their approach to corporate tax policy. The Commission plans to capitalise on this momentum and push forward an ambitious new corporate tax agenda. But EU officials underestimate the task ahead. More modest reforms will deliver better progress.

The Commission’s past attempts to address avoidance have been repeatedly thwarted by the need for member-state unanimity. But times are changing.

As I have previously explained, the international tax agenda is currently dominated by OECD negotiations over two proposals. The first is a global minimum tax rate, which should reduce incentives for multinationals to book profits in low-tax countries. The second is a reallocation of taxing rights between countries, so that the largest multinationals would pay some corporation tax in the countries where they make sales – not just the countries where they book profits. On June 5th 2021, the G7 backed both proposals. The G7 will now seek agreement among the G20, a broader and more diverse group of countries, and then among countries participating in the current OECD discussions. Most countries will engage with the proposals rather than rejecting them. However, there are still two big hurdles to clear.

The first concerns the minimum tax rate. Globally, the minimum tax proposal will work without unanimous agreement because it makes low-tax models far less attractive. However, resistance from some EU member-states could still make it hard to introduce in the EU. The Commission wants to implement any global minimum tax through EU laws. There are good reasons for this approach. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) previously examined whether one EU member-state could stop its companies benefiting from another EU member-state’s lower tax rates (effectively creating a minimum tax rate). The ECJ decided this tax regime limited the freedom of businesses to establish themselves anywhere in the single market, and it should only apply to companies which used a “wholly artificial” structure to avoid tax (such as using corporate entities with no genuine local economic activity). This is difficult to prove. The global minimum tax will not be limited in such a narrow way, so any law that implements the proposal could be challenged at the ECJ. An EU law is more likely to survive such a challenge than national laws.

An EU law would require unanimity, however, which would allow any member-state to veto it. Some member-states that facilitate aggressive tax practices, such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg, have indicated they would not hold back a deal. Ireland, Hungary, and Malta are equivocating, while Cyprus’ finance minister Constantinos Petrides has said Cyprus will block any EU-level directive. If this happens, the EU could proceed with a ‘coalition of the willing’ under the ‘enhanced co-operation’ procedure, whereby a minority of member-states can pursue common policies without the rest. But this could raise the legal risk of the proposal, because it would involve some EU member-states depriving their firms of lower tax rates potentially available in other member-states: an outcome the ECJ previously prohibited. The US and supportive EU member-states will therefore need to pressure EU tax havens not to disrupt the reforms.

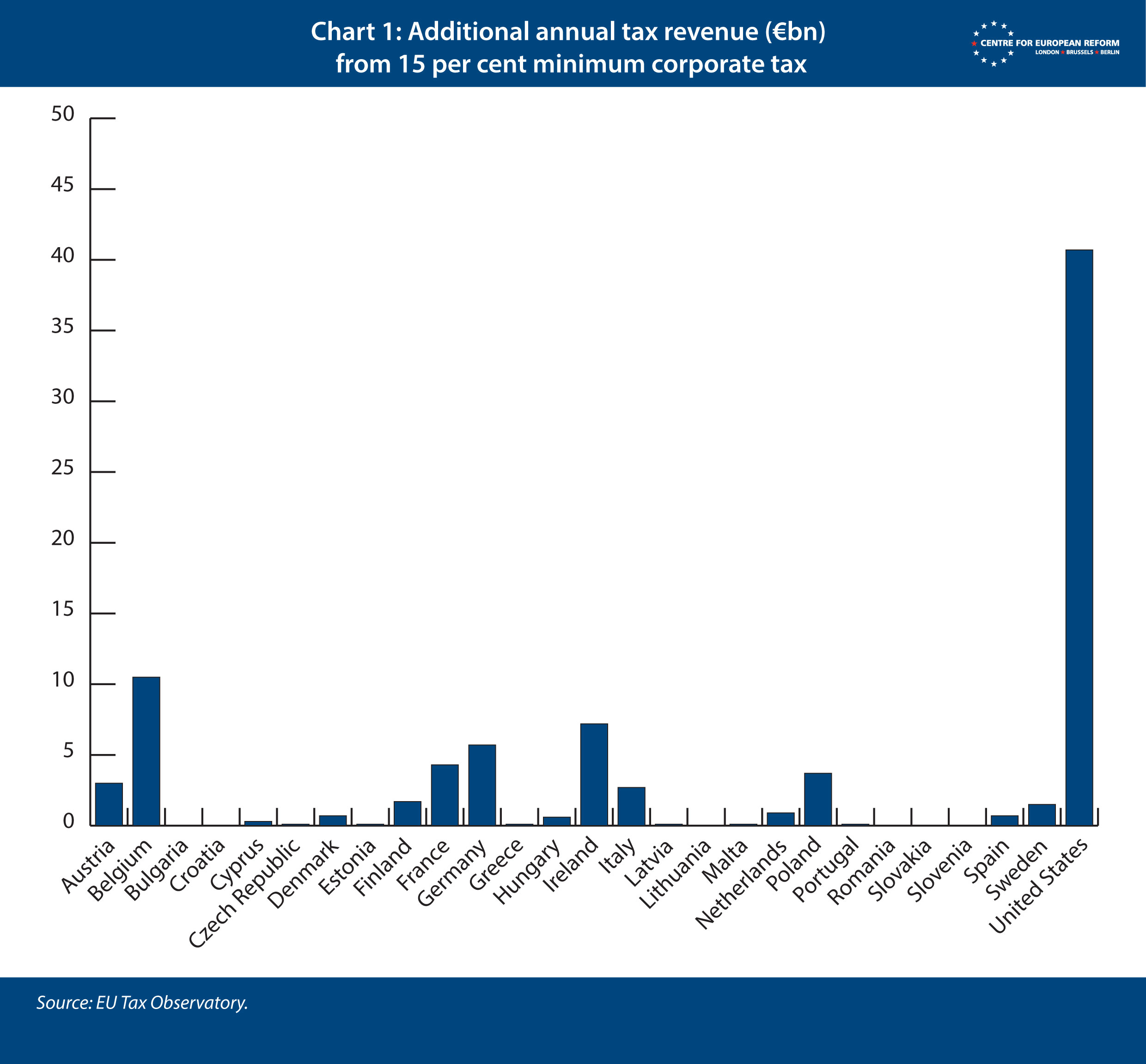

The second hurdle relates to the reallocation of taxing rights between countries: this will require amending a vast number of international tax treaties. Tax rights cannot simply be reallocated by a ‘coalition of the willing’. Low-tax countries where foreign multinationals’ profits are currently booked may not agree to treaty changes. The UK and EU also doubt whether the US Congress will accept the reallocation proposal, even if the Biden administration does so. Congress may be reticent because the European Commission still insists it will impose a ‘digital levy’, despite the US requirement that countries remove their digital services taxes to achieve a deal at the OECD. The G7 communiqué appears to be carefully worded – referring vaguely to the removal of “Digital Services Taxes, and other relevant similar measures” – to disguise disagreement on this issue. If the reallocation is not implemented, that may put the minimum tax at risk: EU member-states will benefit little from the minimum tax rate (see Chart 1), and therefore will not accept it without the tax reallocation. If the reallocation of taxing rights does not proceed, the whole reform package may collapse.

The UK and EU doubt whether the US Congress will accept the proposal to reallocate taxation rights, even if the Biden administration does so.

The outcome of the OECD negotiations is still uncertain. And yet, the Commission is already eyeing even more ambitious tax reforms building on the still-to-be-agreed OECD package. For example, the Commission wants to leverage the OECD proposals to deliver an EU-wide single corporate tax rulebook. Like the OECD tax reallocation proposal, the EU-wide rulebook would identify multinationals’ profits at an EU level, and then allocate taxation rights between member-states using a formula that may include factors such as the location of sales, assets and labour. This would reduce profit-shifting within the EU, deepen the single market by lowering barriers to firms operating across multiple member-states, and lower tax administration costs for businesses.

The outcome of the G7 tax deal is still uncertain but the European Commission is already eyeing even more ambitious tax reforms.

The Commission’s plan does not include harmonisation of corporate tax rates. But it would still constrain how EU countries use tax policy to attract investment. For example, member-states might be prevented from giving tax incentives to certain types of investment. This will irk some EU capitals; Ireland has already said it has “significant concerns” about the Commission’s plans. The Commission might gather more support for its new tax plans by focusing on securing member-state support for the OECD proposals, and developing its tax plans afterwards. Change may come sooner than expected: once the OECD agreement has been secured, countries will adjust to the new international reality. As Ireland and the Netherlands, for example, are forced to become less dependent on aggressive tax policies, their consent for a deeper integration of tax policies might be more easily secured. Given national tax rates will be the remaining means of EU member-states competing with each other for investment under the Commission proposals, member-states which tax at the minimum global rate in future (which may include Ireland, for example) may even see competitive benefit in harmonising other aspects of EU corporate tax policy.

But if the Commission chooses to push its proposal for a single rulebook now, it risks provoking even more opposition from member-states for the OECD proposals. Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis has implied the Commission might circumvent vetoes, through a provision in the EU treaties which allows a qualified majority of member-states to act to eliminate ‘distortions’ in the single market. Use of this provision would be likely to result in lengthy legal challenges – and would be unlikely to persuade reluctant member-states to constructively engage.

The single corporate tax rulebook is not the only tax reform the Commission hopes to achieve without EU unanimity. The Commission is also trying to condition low-tax member-states’ use of COVID-19 recovery funds on domestic tax reform. Member-states have prepared national plans for the use of their recovery funds, which the Commission assesses against its country-specific recommendations. The Commission has singled out six member-states in those recommendations – Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands – for their narrow tax bases or for facilitating “aggressive tax planning”. The Council of Ministers must approve national plans by a qualified majority: there is no need for unanimity.

Some member-states have made limited concessions on tax as part of the plans: for example, Luxembourg proposes to discourage payments to the EU list of tax havens and Cyprus will do so for a broader list of low-tax jurisdictions. But some of the member-states of most concern are not big winners from the recovery fund: for example, of the €338 billion in grants available, the Netherlands is only eligible for €6 billion, Ireland less than €1 billion and Luxembourg less than €100 million. The Commission therefore has little leverage to convince key member-states to enact wholesale tax reforms. More importantly, the Commission will want to ensure the broadest possible member-state support for the fund, to provide political weight if the Commission needs to challenge potential misuse of funds by Poland and Hungary – which have challenged an EU law linking EU funds to compliance with the rule of law. Given this context, the Commission, and other member-states, will not reject national plans on the basis of tax policy concerns alone.

Neither the OECD negotiations nor the COVID-19 recovery funds are therefore likely to open a pathway for broader tax reforms in the EU. More realistic reforms would aim instead at tax transparency.

‘Country-by-country reporting’ is a recent example of how the Commission can achieve success. The Commission’s original proposal would require large multinationals to publish how much tax they pay in each country, thereby helping to publicly identify aggressive tax planning and the countries which facilitate it. The Council and the European Parliament recently reached a compromise over the proposal, agreeing to only require large multinationals to disclose tax paid in EU member-states and in countries the EU deems ‘non-co-operative’ on tax matters (a list which excludes many tax havens), not in each country globally.

The Commission’s plans are not perfect. But they could encourage EU member-states, and the public, to pressure for tax reform in countries that continue to facilitate tax avoidance. To ensure that no country could veto the introduction of reporting obligations, the Council is treating this proposal as an accounting, rather than a taxation, measure (accounting laws do not require unanimity). By this token, the EU could also decide to consider other transparency steps as accounting measures. For example, recent suggestions to force large companies to publish their effective corporate tax rates, and to require member-states to monitor and report on the use of shell companies (which can be used for aggressive tax planning), may be able to circumvent unanimity too.

The OECD tax proposals still have a difficult path ahead and their implementation is not assured. The Commission should focus on ensuring EU member-states do not stand in the way of these proposals. Its attempts to put forward an ambitious tax agenda – piggy-backing on the OECD negotiations and the COVID-19 recovery fund – are unlikely to work and could even dissuade countries from agreeing to the OECD package. Tax transparency proposals will not directly tackle harmful tax policies. However, they are more politically realistic and, in the long term, create more political pressure on low-tax countries to change their behaviour and not to obstruct future reforms. Luxembourg's and the Netherlands’ support for a global corporate minimum tax shows that political pressure can help persuade low-taxing countries to change course. Transparency measures should lead others to follow suit.

Zach Meyers is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment