Avoiding the pitfalls of an EU carbon border adjustment mechanism

A leaked draft of the EU’s CBAM regulation provides fresh insights into what the Commission plans to do. But it also raises a number of tricky questions.

The EU wants to introduce a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) to ensure its climate change mitigation measures are effective and do not lead to so-called carbon leakage. Imports would be subject to a carbon-related fee, reflecting the costs that the EU imposes on domestic producers under its emissions trading system (ETS). While the proposal might still change ahead of publication, a leak of the European Commission’s draft CBAM regulation and annexes provides fresh insight into the EU’s approach. It also raises a number of questions on the impact on small and medium sized importers, developing countries, the allocation of free allowances and the UK.

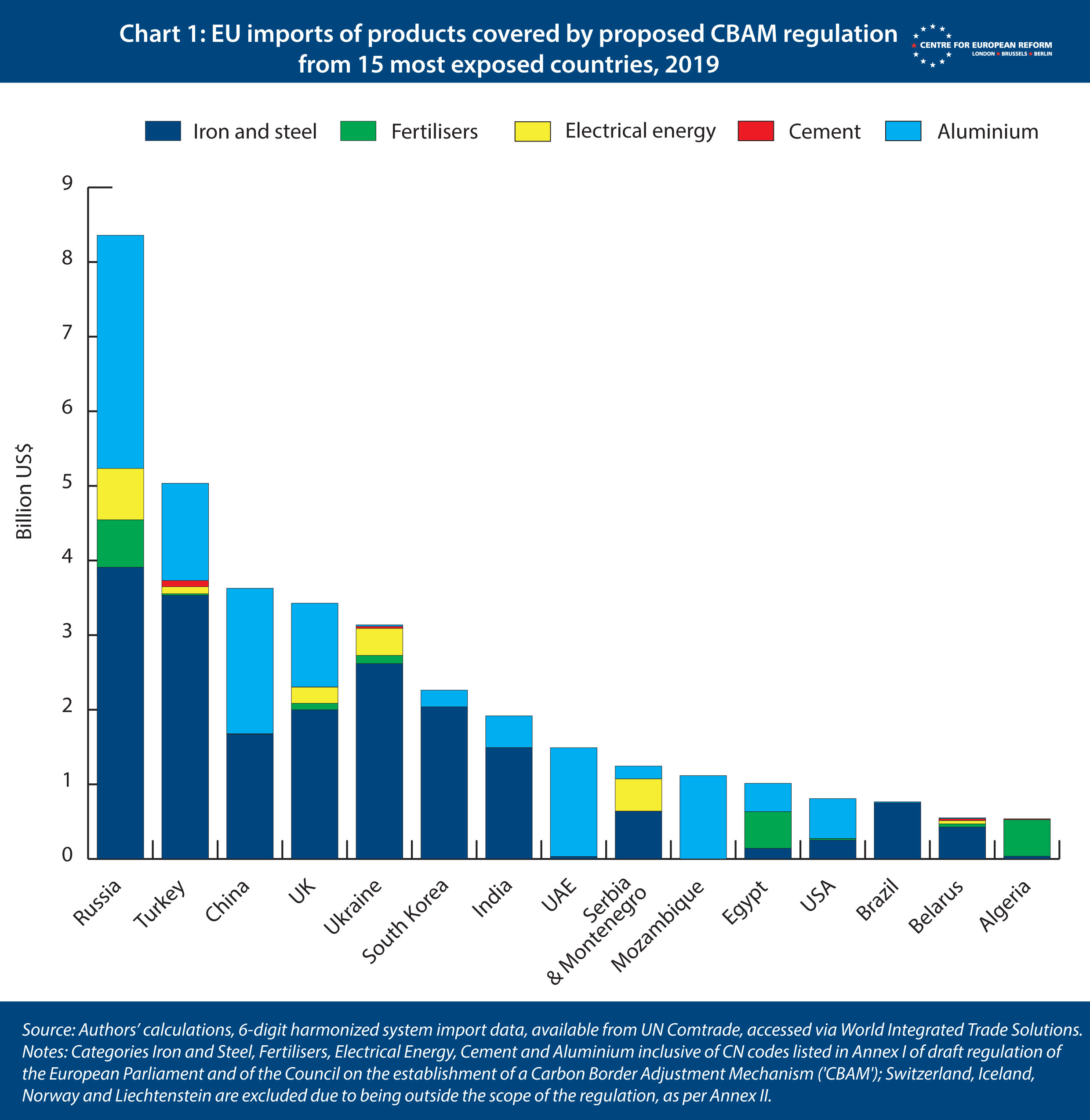

The Commission wants the CBAM to cover importers of electricity, iron and steel, cement, aluminium and some fertilisers in the first instance, but it could be extended to cover additional sectors in the future. The initial list of sectors is fairly narrow, and does not include a number of industries covered by the EU’s ETS such as other chemicals, ceramics and paper. However, as an opening gambit, the choice of industries has a political logic, if the Commission is still hoping for the US to implictly accept the CBAM, and avoid further trade disputes. The US is just 12th in the ranking of countries most exposed to the proposed CBAM regulation (see Chart 1).

The initial list of sectors is fairly narrow, and does not include a number of industries covered by the EU’s ETS such as other chemicals, ceramics and paper.

Some countries are exempted from the CBAM altogether. Switzerland has already linked its ETS to the EU’s, and the European Economic Area (EEA) countries Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway participate in the EU’s ETS. More countries could be added to this list if they either fully integrate within the EU’s ETS, or link their own ETS to the EU’s.

In order to comply with the new CBAM regulation, importers of the covered goods would need to obtain authorisation from a newly created CBAM authority, and purchase CBAM certificates. The price of these certificates would be tied to the weekly price of ETS permits sold to domestic producers. By May 31st every year, importers would need to submit a declaration containing their independently verified emissions calculations for the past year, and surrender the equivalent number of CBAM certificates. If the importer had more CBAM certificates than it needs at the end of the year, the CBAM authority would re-purchase up to 10 per cent of certificates that the importer has purchased during the previous year, but any extra would be cancelled.

Companies would face two options when calculating the amount of carbon embedded in their imports. The default method would assume the emissions per tonne of an import to be equal to the average emissions per tonne of the worst 10 per cent of emitters among EU producers of the same good. Such a ‘punitive’ high price should provide an incentive for importers to engage in innovative production practices to reduce their emissions, and to document them in order to pay a lower CBAM price, as per the second option. Here, importers would calculate actual emissions, using prescriptive formulas that would also allow them to take into account any carbon price paid in the country of origin. In the three-year transition to the new CBAM regime, the Commission would set a benchmarked carbon price for importers based on the average carbon emissions of producing the good in the EU.

The draft regulation does not provide a formal definition of foreign ‘carbon prices’ which would be recognised by the CBAM authority. Presumably the CBAM authority would recognise carbon prices set either through ETSs or through carbon taxes. Translating regulatory constraints on emissions into implicit prices would be a lot more complex. But the EU should go the extra mile to account for regulation, and thus acknowledge different approaches to climate action. At present, regulatory approaches to carbon mitigation might be the only way for some trade partners, such as the US, to make good on their climate pledges.

The Commission has designed the CBAM to operate as an extension of the EU ETS. The EU probably had in mind that its CBAM needs to be compatible with the EU’s WTO commitments. If a legal challenge occurred, the EU would have to demonstrate that it is not unfairly discriminating against imported products. However, the CBAM approach based on importers’ authorisation, on third-party verification of emissions and on the purchase and surrender of certificates would introduce a large amount of additional administrative costs for importers. These costs would apply even to importers of products from jurisdictions where carbon pricing applies, who therefore do not have to purchase and surrender any CBAM certificates because the carbon price has already been paid in the country of origin.

The CBAM approach based on importers’ authorisation, on third-party verification of emissions and on the purchase and surrender of certificates would introduce a large amount of additional administrative costs for importers.

The impacts of the CBAM on small businesses

These administrative costs will be particularly burdensome for new and smaller businesses. For example, the draft regulation states that companies less than two years old seeking import authorisation from the CBAM authority will have to provide a guarantee that they are able to cover the predicted cost of purchasing CBAM certificates for the current and forthcoming year. The process for declaring emissions also imposes a disproportionate burden on smaller companies, which are less likely to have the resources to professionally certify the carbon content of their entire supply chain. For this reason, small and young companies may have to use the punitive default method of calculating the imported carbon, or stop importing altogether and instead purchase from specialised importers. Both are bound to make small companies’ inputs more expensive.

To address this issue and help small businesses adjust, the EU should consider a number of options, including underwriting guarantees and providing loans and grants for training and for covering the cost of third-party certification, as well as supporting the creation of specialist intermediaries. The EU should also allow small businesses to continue using the more accommodating benchmark prices proposed for the transition period – indefinitely or for a longer adaptation period.

The impacts of the CBAM on developing countries

As one of the authors has previously argued, least developed countries (LDCs) should be exempted from the CBAM. It is unreasonable to expect businesses in poorer countries to shoulder the same burden as businesses in countries that are richer and have historically contributed a larger share of global cumulative carbon emissions. Yet the draft proposal does not include such a waiver. The Commission may be wary about including any exemptions, because positive discrimination in favour of LDCs could be hard to legally justify. WTO provisions currently allow countries to afford preferential tariff treatment to imports from developing countries, but extending this preferential treatment to a regulatory measure such as the CBAM would probably require further negotiation and agreement among WTO members. The Commission also worries that exemptions could undermine the raison d’être of the regulation: preventing carbon leakage. The Commission may also argue that least developed countries, with the notable exception of aluminium exports from Mozambique, do not export large quantities of the products covered by the CBAM anyway.

But the EU should reconsider. First, while LDCs would, for the most part, not be significantly impacted by the proposed iteration of the CBAM, the Commission has left open the possibility of adding to the list of sectors covered by the CBAM in future. Second, while the import figures for LDCs might be relatively small, these can be of economic significance to the poorest countries and their exporters. Third, exempting LDC imports would not harm the regulation’s climate objective, as the quantity of exports from LDCs to Europe is small. An LDC waiver might require further discussion with WTO members, but remains the simplest way to address the problem. To see why, consider two alternatives to a waiver to get to the same outcome.

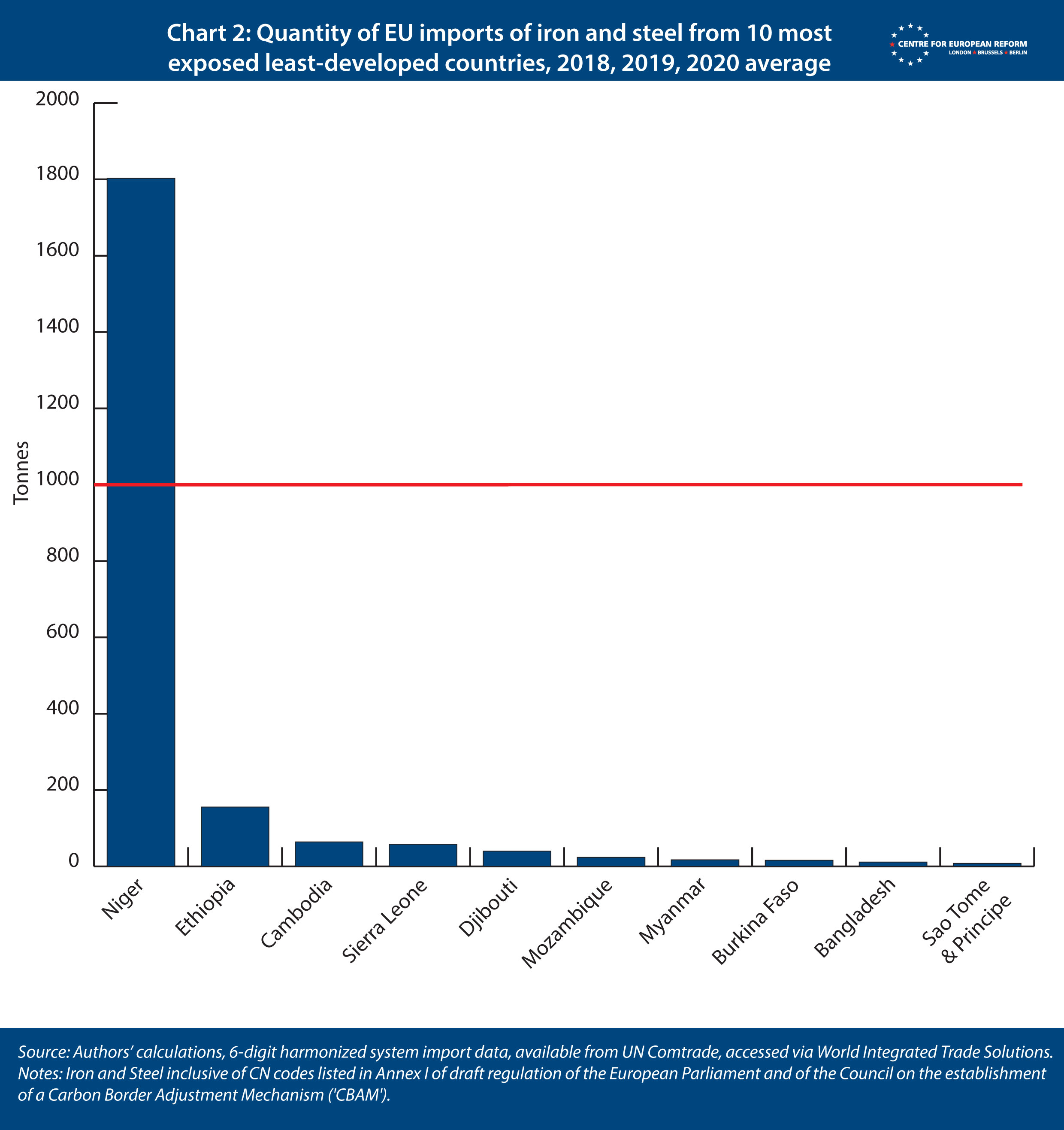

The EU could introduce a minimum threshold, which would exempt all imports below a certain quantity or value from the CBAM regulation, no matter their origin. Universal application of this exemption to all imports under the threshold (for example, all shipments of steel under 1000 tonnes) would avoid the EU running into claims of discrimination. Exemptions based on the quantity or value of a given shipment could create perverse incentives – for example, companies might import in smaller batches, or through different legal entities, to dodge the CBAM levy. However, the draft CBAM regulation already includes provisions guarding against circumvention of the CBAM, which could be used to penalise companies abusing the exemption.

Another approach could be to exempt imports of selected products so long as the average quantity imported from a given country (perhaps a three-year rolling average) remained below a set level, 1000 tonnes for example [marked with a red line in Chart 2]. The provisions could include safeguards to guard against a surge in imports and circumvention. Such an approach would prove beneficial to most LDCs in practice, and also to exporters in other countries that only sell small quantities of CBAM goods to the EU. However, it would not remove all of the additional administrative burden, with importers of CBAM goods still being required to register and declare imports to the CBAM authority. It might also lead to claims of de-facto discrimination from other WTO members, if their exporters do not benefit. Also, choosing and justifying the exemption level could prove tricky.

Regardless of the approach chosen, the EU should engage with developing countries to support their shift away from carbon-intensive production processes, both through capacity building and by devoting part of CBAM revenues to climate finance, as others have also suggested. This would, in the longer run, also reduce the CBAM burden these countries would shoulder.

The impacts of the CBAM on Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The CBAM’s potential impact on the UK is also worth considering. Due to its proximity and historical economic integration with the UK is one of the countries more exposed to the EU’s CBAM, in particular its exports of iron, steel and aluminium. It is in the UK’s interest to be fully exempted, as is the case for the EEA countries and Switzerland. A full exemption remains a possibility, if the UK chooses to connect its own ETS to the EU’s, but at the time of writing the UK has not decided.

Still, because the UK ETS subjects some British goods to a domestic carbon price, EU importers of such British goods could take the UK price into account, and benefit from a reduction in the number of CBAM allowances they would need to surrender. But there will be unavoidable new costs associated with CBAM bureaucracy, given importers would still need to register with the CBAM authority to prove that their imports have already been subject to a carbon price. Furthermore, the CBAM’s potential interaction with the Northern Ireland protocol could make things more tricky, and gives extra weight to arguments in favour of the UK linking its ETS to the EU’s.

The first question is whether the CBAM regulation falls within the scope of the Northern Ireland protocol. It probably should, in order to prevent carbon-intensive imports dodging the new levy by entering the EU market via Northern Ireland. However, it is not clear how this would function in practice. The EU’s ETS applies only to electricity generation in Northern Ireland, while the UK’s ETS applies to everything else. So the legal basis for any additional charges on CBAM goods entering Northern Ireland would be shaky, due to there being no link to a domestic EU pricing mechanism (other than for electricity). Alternatively, (non-electricity) exports from Northern Ireland to the EU could be subject to the CBAM (requiring EU buyers to register and make declarations), but this would undermine the purpose of the protocol, and create a new regulatory trade border between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

Another alternative would be to extend the ‘not at risk’ procedure, which currently allows some goods to dodge EU tariffs when entering Northern Ireland, to CBAM goods. This would allow CBAM goods to be exempted from CBAM-related bureaucracy when imported into Northern Ireland from Great Britain so long as the importer can prove they will not be moved into the EU. However, this does not resolve the issue for CBAM goods produced in Northern Ireland, which could continue to be freely sold into the EU. Regardless, the Commission must consider these questions before tabling the regulation. If Northern Ireland is within the scope of the CBAM, the EU will need the UK’s agreement to see it implemented in the territory. Failure to agree could lead to political tension and a trade dispute. From a UK perspective, the obvious solution is to link its own ETS to the EU’s, therefore exempting UK exports to the EU (from both Northern Ireland and Great Britain) from the CBAM regulation.

If Northern Ireland is within the scope of the CBAM, the EU will need the UK’s agreement to see it implemented in the territory.

Free EU ETS allowances

Under the EU ETS, heavy industry is granted free allowances because of its exposure to international competitors who are not subject to carbon pricing. The alternative is paying for allowances via auctions, which is what some sectors need to do, to cover at least part of their emissions. Free allocation of carbon emission allowances aims to avoid carbon leakage, which would occur if producers moved production out of the EU to countries with less stringent environmental policies. Under current regulations, sectors at most risk of relocation will obtain the entirety of their ETS allowances for free until 2030. Conversely, sectors at lower risk will obtain at most 30 per cent of their allowances for free after 2026, and none by 2030.

Introducing a CBAM adds a layer of complexity. A CBAM is another method to avoid carbon leakage, by requiring importers to pay an equivalent carbon price, rather than exempting domestic producers from it. Once a CBAM is in place, there is thus no rationale for free allowances: maintaining them could amount to double protection of domestic industry, and undermine the CBAM’s climate objectives. The best approach would be to speed up the replacement of free allocation of allowances with auctions in all sectors at risk of outsourcing which are covered by the CBAM. This would be justified by the increased ambition of newly approved 2030 climate goals.

Once a CBAM is in place, there is thus no rationale for free allowances: maintaining them could amount to double protection of domestic industry, and undermine the CBAM’s climate objectives.

But the draft CBAM regulation does not give any indication as to what the EU’s long-run plan for free allowances is. Rather, it states that as a transitional provision, the number of CBAM certificates an importer will need to surrender at the end of a given year will be reduced to take into account the impact of ETS free allowances on the domestic carbon price of the same kind of goods. While that is a decent compromise, it will dampen incentives for industrial decarbonisation in the short term – both in the EU and elsewhere.

Leaked information about the forthcoming EU ETS reform point to the Commission as willing to remove free allowances for CBAM-exposed sectors, but the timeline for this is still unknown. However, reports of internal Commission estimates show that the EU expects free ETS allowances to continue until at least 2030 or even 2035. This type of double protection of domestic heavy industry would no doubt delay the low-carbon investment needed to make production processes climate-proof. Additionally, it could make it harder for the EU to defend its CBAM at the WTO, if the ETS free allowances are deemed to confer an additional advantage to domestic industry which foreign producers do not enjoy.

It is possible that the CBAM draft regulation has leaked just to gauge reactions from industry and other stakeholders, so the Commission can then decide how to refine it before the official publication scheduled for mid-July. It is also possible that the CBAM regulation will change significantly before it is officially published. It will then inevitably be altered further following member-states and European Parliament engagement. But regardless, the Commission should use the coming month to refine the proposal, and see off some of the inevitable criticism in advance.

This work is being supported by a grant from the European Climate Foundation.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment