Preparing for a softer Brexit

British Prime Minister Theresa May’s first government was committed to a hard Brexit: one that prioritized sovereignty at the expense of close economic ties. She said she would exclude the European Court of Justice (ECJ) from post-Brexit Britain; implied that she wanted the number of EU immigrants to fall significantly; and argued for Britain to leave both the customs union and the single market. But the June 8th, 2017, election took away May’s majority, greatly weakening her, and the new Parliament seems unlikely to pass the legislation required for a hard Brexit.

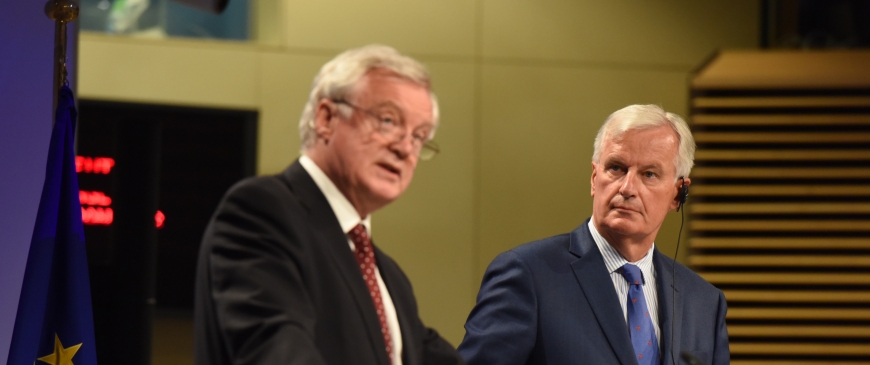

Since the election, May and David Davis, her secretary of state for leaving the EU, have said that they are sticking to existing Brexit plans. Nevertheless, just a handful of pro-EU Conservative MPs could defeat the government if they joined forces with the opposition, most of which wants a softer Brexit.

Policy in flux

On June 21st, 2017, the Queen’s Speech from the Throne outlined eight pieces of legislation that Brexit would require over the next two years, covering trade, customs arrangements, international sanctions, nuclear safety, agriculture, fisheries, and immigration, as well as the ‘repeal bill’ that will transform existing EU rules into British law. It seems implausible to suppose that all of that can be passed unless the government softens its stance.

Negotiations between Davis and his opposite EU number, Michel Barnier, began on June 19th, 2017. The first few months will focus on the legal separation set out in Article 50—notably the rights of EU citizens in Britain and vice versa, the UK’s financial obligations, and the question of the border with Ireland—rather than the future relationship. This gives the government several months to rethink its approach to the future economic relationship. Whatever May and Davis are saying in public, Brexit policy is in fact in flux.

The coalition of forces pushing for a softer Brexit is considerable. Business lobbies seem to have more access to senior figures in the government than they did before the election, and are exploiting that opportunity to push for a rethink. The Treasury, long an advocate of retaining close economic ties to the EU, is newly emboldened. Before the election, Chancellor Philip Hammond was expecting to be fired, but the weakness of the prime minister means that he is now unsackable, and he is making a strong case for a business-friendly Brexit. The Scottish Tories, led by the feisty Ruth Davidson, want a softer Brexit, as do the Scottish and Welsh administrations and—in certain respects—Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party, on whose parliamentary support May now depends.

The Labour Party, in a stronger position since winning 40 percent of the votes in the election, is calling for a softer Brexit, though it is divided over exactly what it wants. Keir Starmer, its Brexit spokesman, says that a UK-EU customs union should be considered, while other Labour MPs want to stay in the single market. Former Conservative leaders, such as John Major and William Hague, have called on the government to reach out to opposition leaders to work out a national strategy for Brexit, as has the Archbishop of Canterbury. Influential Conservative columnists—including the Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Jeremy Warner, Juliet Samuel, and Allister Heath—have called for various versions of a softer Brexit. Even passionate Brexiteers like Michael Gove, who has re-joined the cabinet as environment secretary, and Steve Baker, who has become junior minister for Brexit, have suggested rethinking the Brexit strategy.

Yet May persists in saying that nothing needs to change. Many Eurosceptic Conservative MPs are backing her as their best hope of achieving the hard Brexit they desire. Some of them are letting it be known that, if she softens, they will trigger a leadership contest. Their willingness to bully opponents—reinforced by the power of the Eurosceptic press—has worked in the past, and they seem confident that it will work again.

In the short term, the easiest thing for May to do is to press ahead with the Brexit that her right wing desires. But that is probably not sustainable in the longer term. If she wants to avoid parliamentary defeats, she will need to collaborate with Labour and other opposition MPs. As Yvette Cooper, a senior Labour figure, has suggested, May should establish some sort of parliamentary framework in which government and opposition politicians can hammer out common objectives and a broad approach to Brexit strategy. It would then be up to the government to deliver on that strategy, before reporting back to Parliament.

At the moment, it seems hard to imagine that May could commit to such a volte-face. She would have to alienate a hard core of Conservative Brexiteers, and thus risk splitting her party. May might also be deterred by the difficulty of working with the Labour Party. Some Labour leaders would be reluctant to help the government, as its collapse could trigger another election. But others see an opportunity to split the Tories and gain credibility with the public by being seen to act responsibly in the national interest.

In any case, if May doesn’t reinvent herself as a soft-Brexiteer, she is likely to be defeated in Parliament. Although talking to Labour about Brexit strategy would alienate her right wing, many Conservatives would probably back such a move. They want Brexit rather than any particular version of it, and know that if the government falls the result could be an election that brings Jeremy Corbyn to power.

How would it look?

If May cannot bring herself to work with the opposition, and she falls, her successor will find that survival means working with the opposition to achieve a softer version of Brexit. But what could a soft Brexit look like?

Staying in the single market, perhaps along the lines of Norway in the European Economic Area (EEA), is unlikely. The EU would insist on free movement of labor—a price that a majority of Conservative and Labour MPs would not want to pay. Nor would other aspects of the EEA appeal to many MPs, such as making substantial payments to the EU budget, accepting (indirectly) the adjudication of the European Court of Justice, and adopting all EU single market rules without having a vote on them.

British politicians keep imagining that the EU is about to drop its insistence on free movement as the price for membership of the single market, but there is scant evidence for this. Others argue that Articles 112, 113, and 114 of the EEA enable its members to restrict free movement. In practice that is untrue: Norway has never wanted to use these clauses, since the EU would then have the right to retaliate by restricting trade. So unless the British public abandons its hostility to unrestricted EU migration, there is little chance of Parliament voting to stay in the single market.

But that is a question for the longer term. A softer Brexit will mean a serious transitional phase, to cover the years that will elapse between the moment the UK leaves the EU and the moment its future free trade agreement (FTA) takes effect. Before the election, May was reluctant to commit to a transition, believing (bizarrely) that the FTA could be negotiated in less than two years; she merely agreed to an ‘implementation phase’ while the provisions of the FTA were being phased in. But the Treasury, spurred on by business leaders, is now pushing hard for a proper transition, and it is winning the argument.

The transition will probably look rather like the EEA (but would not be the EEA, since for the UK to remain in the EEA once it had left the EU, it would have to accede to the EFTA treaty). The Treasury hopes that the EU27 will tweak the transitional arrangements to make them a bit more palatable to the British than the EEA. In particular, might Brussels grant London an emergency brake that really could be used against a sudden influx of EU migrants?

What it could look like

As for the longer term relationship, a softer Brexit could mean some combination of four things. One could be to introduce only modest curbs on free movement. The controls will probably be softer than those initially envisioned by May and her recently-sacked chief adviser, Nick Timothy. This is because many leading Leavers—including David Davis, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, and International Trade Secretary Liam Fox—advocate only limited restrictions on migration. Access to EU labor is probably the number one concern of businesses in the UK; the Treasury, representing their views, may well win much of the argument.

A second characteristic of a softer Brexit could mean staying in some EU regulatory agencies—certainly in the transition, and possibly in the long term. The Confederation of British Industry has identified 34 key agencies covering agriculture, energy, transport, and communications, in which Britain will have to either stay or create new bodies.

The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), for example, authorizes British aircraft to fly. The European Medicines Agency advises the European Commission on which drugs should be licensed for sale across the EU. Euratom regulates the trade of nuclear materials. The European Securities and Markets Authority oversees the regulation of securities markets—and so on. Setting up new agencies or expanding existing national ones would be expensive and time-consuming. Does it really make sense for the UK to build up its Civil Aviation Authority into a full aviation safety agency, when EASA works perfectly well?

Yet if Britain wishes to stay in EU agencies it will have to submit itself to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, as do, for example, the non-EU members of EASA.

Indeed, the third characteristic of a softer Brexit could be a less dogmatic rejection of any role for the ECJ. If May continues to make this an indelible red line, she will severely limit the scope of the agreements that cover the future relationship. Thus if (as its airlines hope) the UK wants to stay in the single market for aviation, it will have to accept ECJ rulings, as do Norway and Iceland. The same dilemma applies to many other areas, like financial services, electricity, data flows, and security cooperation.

The EFTA court, which polices single market rules in the non-EU members of the EEA, could offer a possible way forward. If a new court to adjudicate on disputes between the UK and the EU were modelled on the EFTA court, it would include British judges, broadly respect the rulings of the ECJ, and have the freedom to develop its own jurisprudence where the Luxembourg Court had not ruled, or not ruled recently. The EU’s governments and institutions could live with that kind of compromise—if the UK could swallow it.

Customs Union

The fourth and most controversial aspect of a softer Brexit could involve a customs union between the UK and the EU. Britain will have to leave the customs union of the EU, but could, like Turkey, create a customs union with the customs union of the EU. That would mean maintaining the common external tariff and accepting any changes made to it by the EU. Goods would then move easily across frontiers, as today, without the need for checks to see that tariffs had been paid, rules of origin respected or customs forms filled in. This would be hugely beneficial to firms that use just-in-time systems, notably those making cars and aircraft, as well as many retailers; it would also be useful to small businesses that have grown used to exporting to the EU without any paperwork; as well as to farmers who need to move food across frontiers speedily.

Moreover, Britain would continue to benefit from the 50-odd FTAs that the EU has negotiated with other countries (though concerning the EU’s future FTAs, the UK would have to ask for special arrangements so that it was included; given the size of the UK economy, both the EU and the third country concerned would probably want to include the British). One major dividend of an EU-UK customs union would be to obviate the need to re-establish a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland; without a customs union, it is hard to see how border controls of some sort can be avoided.

If Britain were to opt for a customs union, it would have to sign mutual recognition agreements with the EU in order to avoid border checks for compliance with EU standards. But an FTA between the EU and the UK would, in any case, require Britain to agree to EU standards. An EU-UK customs union would have to have a dispute settlement mechanism, but this need not involve the ECJ (to all intents and purposes, the ECJ plays no role in the EU-Turkey customs union, for example).

The main disadvantage of a customs union with the EU would be that Britain would not be able to negotiate new FTAs covering goods with other countries (since customs unions do not cover services, Fox would be free to negotiate services agreements with other countries). This would go against the narrative honed by many Eurosceptics, including Johnson and Fox, about a ‘global Britain’ in which FTAs with ‘Anglosphere’ and BRICS countries would enhance the dynamism of the British economy as it breaks free of the shackles of the moribund Eurozone.

Though retaining a customs union with the EU would madden the Tory right, there is a strong macroeconomic case for doing so. According to the Treasury, which has carried out unpublished analyses, the economic benefits of future FTAs would be significantly less than the economic cost of leaving the customs union. Monique Abell at the National Institute of Economic and Social

Research (NIESR) reached similar conclusions in research published in January 2017. She estimated that if Britain had an FTA but no customs union with the EU, its total trade with the world would fall by 22 percent; meanwhile, new trade with the five BRICS countries, as well as with the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, would boost British trade by 5 percent in total.

Furthermore, as the Treasury points out, the costs of leaving the customs union are immediate, while the benefits, via future FTAs, would not become visible for many years. That is why the transitional arrangements will almost certainly include a link to the EU’s customs union. As Hammond said in his recent Mansion House speech:

we’ll almost certainly need an implementation period, outside the customs union itself, but with current border arrangements remaining in place until new long-term arrangements are up and running.

Hammond has not yet risked war with the Eurosceptics by stating in public that linking to the customs union is a long-term option, but he is reported to be in favour of it in private.

Less agreeable than membership

The shape of Brexit, of course, does not depend only on the UK. EU leaders want a deal, but believe they can insist on their terms, since no deal would damage the UK far more than the European Union. They would be happy if the UK sought a softer Brexit, which would be less disruptive for their economies. But they will stick to their principles: the single market must include free movement of people and the jurisdiction of the ECJ; Britain must not ‘cherry-pick’ parts of the market, lest it undermine the EU’s institutional and legal coherence; and life outside the EU must be visibly less agreeable than membership. The EU will make it very clear that if the British want a softer Brexit—that is to say, one that retains a lot of economic integration—they will have to give up sovereignty.

Charles Grant is director of the Centre for European Reform.