British services have played second fiddle in the Brexit debate

In 2018, services accounted for 46 per cent of UK exports, or £297 billion. The EU received 40 per cent of British services exports, and was the origin of 48 per cent of British services imports, the highest proportion of any UK trading partner. Unlike goods trade, where the UK runs a deficit, the UK ran a total trade surplus in services with the EU of £28 billion.

Yet services trade has played second fiddle to talk of trade in goods and manufacturing supply chains in the Brexit debate. This is understandable, in that trade in services is complicated – barriers to trade do not take the form of readily quantifiable tariffs (taxes levied on imports), but are often a convoluted mix of trade and investment policy, domestic regulation, procurement policies and issues surrounding the movement of people.

The EU’s single market in services is not as developed as its single market in goods. It does, however, exist. The OECD estimates that restrictions on services trade between EU member states are around four times smaller than restrictions on selling services into the single market from outside.

Indeed, in some areas the EU has liberalised services trade between its members further than some countries have managed internally. For example, the EU has been more successful in developing a framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications than the US.

After Brexit, the EU and the UK have committed to concluding ‘ambitious, comprehensive and balanced arrangements on trade in services and investment in services and non-services sectors, respecting each Party’s right to regulate’.

Their stated intention is to ‘deliver a level of liberalisation in trade in services well beyond the Parties’ World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments and building on recent Union free trade agreements.’

However, the British government has been clear in its intention to leave the EU’s single market. This desire to be free of the EU’s rulebook, regulatory bodies and oversight means there are limits on what the EU is able to offer in terms of services market access.

While EU free trade agreements certainly do cover most services sectors, and tackle issues such as the number of foreign services providers allowed to operate within its territory, they have little to say about issues like licensing and comprehensive regulatory recognition.

Crudely speaking, the EU’s approach when it comes to services trade is to make it relatively easy for companies to invest and set up offices within its territory while at the same time making it difficult for regulated services to be sold into the EU from outside. And in its free trade agreements, the EU does little more than lock in existing levels of access for third countries, rather than pulling down additional barriers to trade.

For example, while the UK is an EU member state, a law firm operating out of the UK can sell and provide legal services cross-border to clients in any other member state. In contrast, under the terms of a EU-UK free trade agreement, most member states would not let the same law firm sell to clients in their territory unless it has a commercial presence within the EU.

The impact of exiting the single market and moving to a free trade agreement will vary by sector, with highly regulated sectors being more affected.

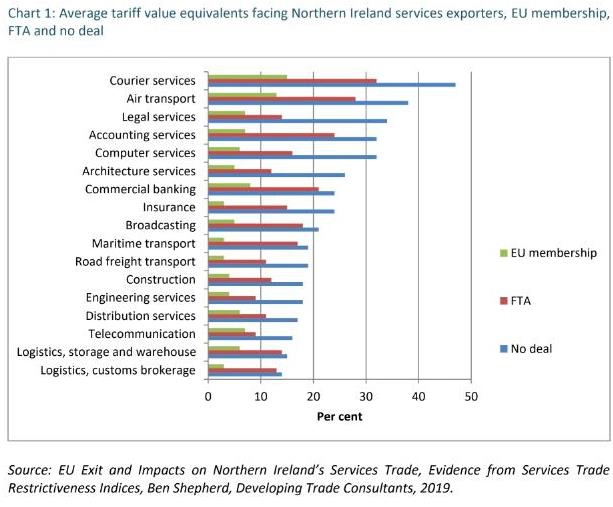

Northern Ireland’s Department for the Economy calculated the tariff value equivalent of the barriers to trade facing different services sectors under three different scenarios: EU membership; a free trade agreement and no deal (Chart 1).

The sectors facing the biggest increase in barriers to trade include accounting services, commercial banking, insurance and broadcasting. (While the study specifically focused on Northern Ireland, there is little reason to think that the figures would differ significantly were it to have focused on the whole of the UK.)

My own estimates, which take into account how UK services providers currently sell to their EU27 based clients (directly from the UK or from EU27 local offices) finds that, compared to the status quo, an EU-UK free trade agreement would have the biggest negative impact on the financial services sector, with transport and other business services also hit to a smaller degree.

However, some negative impacts could be mitigated if the EU and the UK succeed in reaching an ambitious agreement on transport services (including aviation, road, rail and maritime transport), as is their stated intent.

The ability of companies to adapt to changes in circumstance will also vary, with larger firms likely having greater capacity when it comes to planning for post-Brexit disruption than smaller companies.

Equally, the negative impact associated with financial services would be lower if the EU allowed the UK to take advantage of its financial equivalence regime, allowing certain EU27 focused financial services activity to continue in the UK (see section by Sarah Hall).

Any decline in UK-based activity would also probably be staggered over time, as individual EU member state regulators take unilateral measures to ensure an orderly shift in economic activity from the UK to within the EU, so as to avoid a cliff edge and unnecessarily triggering a potential financial shock.

By prioritising regulatory autonomy, and exiting the single market, the British government has implicitly accepted that trading services between the EU and the UK will become more difficult in future.

While a free trade agreement could offer some benefits over trading without one, these will only be marginal. British services exporters will need to adjust their business models accordingly.

By Sam Lowe, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform. This article is part of the Brexit: What next? report.