Brexit is leading to growing Balkanisation for business

This week’s chart is a newsletter exclusive and comes courtesy of John Springford, at the Centre for European Reform. It addresses one of the conundrums of post-Brexit trade patterns that have perplexed researchers and economists.

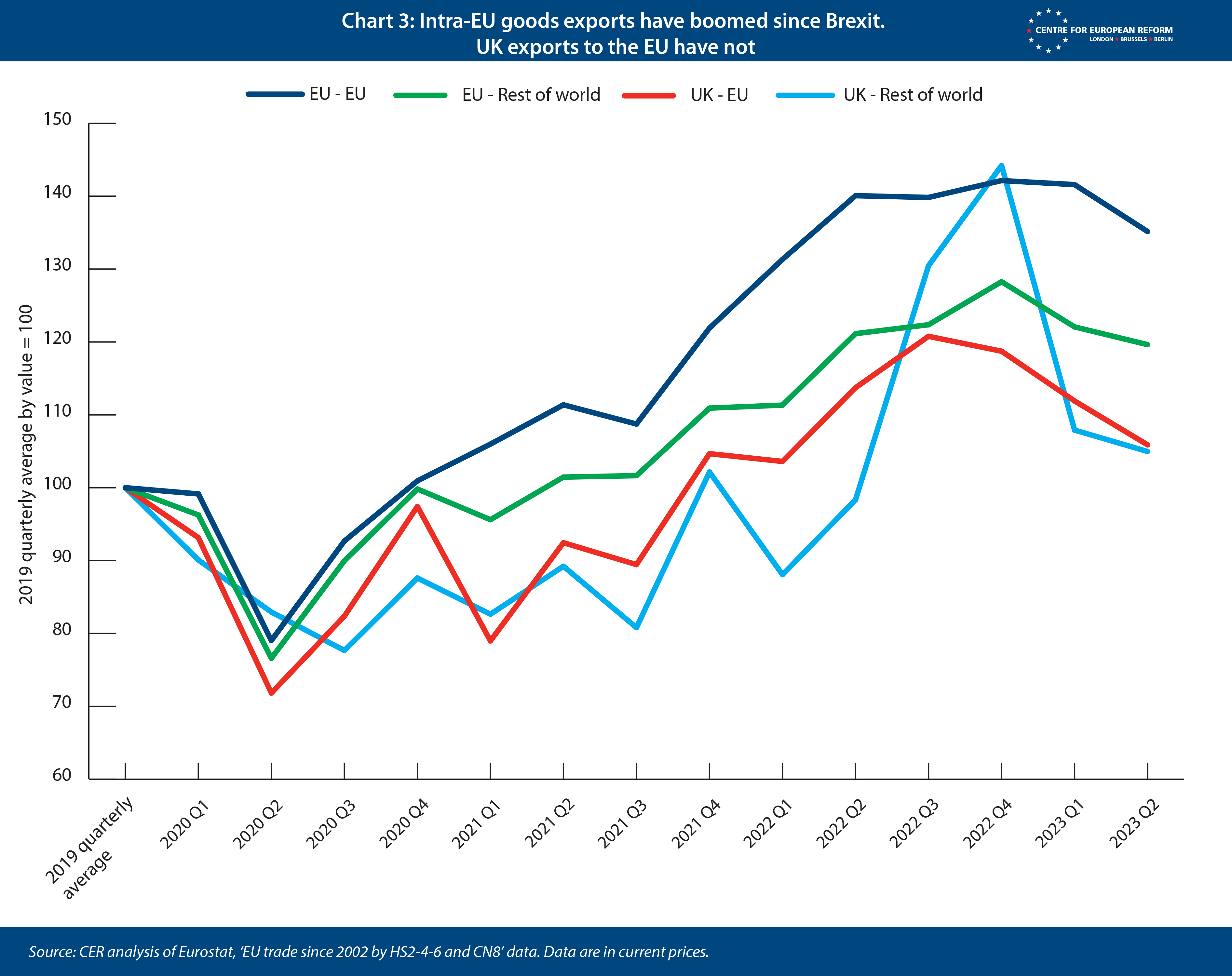

Here’s the question Springford poses: “The UK’s goods exports to the EU have not performed any worse than to the rest of the world, and its services exports have grown strongly. How come?”

On goods trade, the answer — set out beautifully in this short paper — is that the superficially strong headline numbers conceal the fact that when markets reopened after Covid-19 lockdowns the UK got left behind.

What the numbers show is that while trade between EU member states boomed during the bounceback, the UK didn’t get in on the action — and the obvious reason for that, Springford argues, is the barriers to trade erected by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).

If Britain’s total exports to the EU had grown in line with those of EU member-states, they would have been 27 per cent higher than they were in August 2023 (the last month for which we have comparable data). Since exports to the EU make up around half of Britain’s total, this suggests its total goods exports are around 13.5 per cent down, or £13.4bn on a quarterly basis.

So, on the basis of that analysis, as Springford observes, “the fact that EU and non-EU [goods] exports moved together is a sign of weakness, not robustness” because really UK exports to the EU should have been booming.

On services, where the UK has continued to perform strongly — contrary to the pre-Brexit consensus of many economists — Springford also uses a counterfactual analysis that again paints a less rosy picture than the headlines suggest.

Although UK services exports growth has outperformed the average of advanced economies in some categories — such as business services (consulting), insurance and pensions — in two important sectors that are both exposed to the barriers created by the TCA — financial services and transportation — the UK performance is below par.

If the UK’s exports in these two sectors had performed in line with the global average of advanced economies from single market exit to the second quarter of 2023, then Britain’s total services exports would be 11 per cent, or £10bn higher in that quarter. Again, that’s broadly in line with the 4-5 per cent hit to GDP.

Taken together, the “hit” against the counterfactual is about £23bn, which Springford notes is consistent with the counterfactual modelling that predicts a 4 to 5 per cent hit to gross domestic product from Brexit, predicated on a 10 to 15 per cent hit to trade in both goods and services.