Brace yourself for the next Brexit faultline: The battle over transition

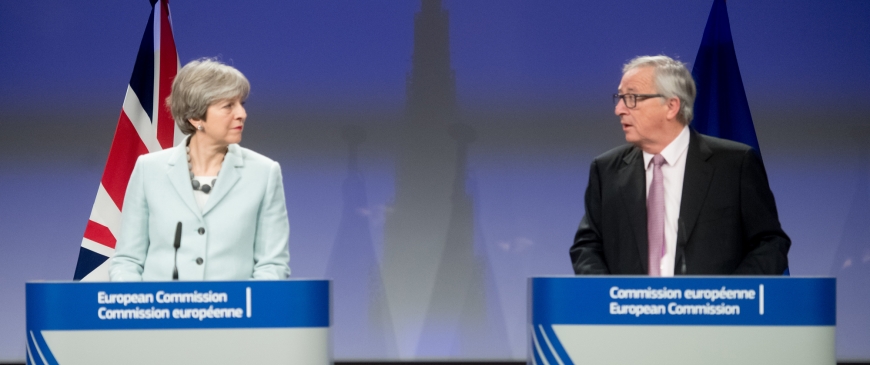

European Union leaders have confirmed that “sufficient progress” has been made to move Brexit talks on to the terms of transition and a future trade relationship between the EU and Britain. The EU’s strategy – impose a series of deadlines that force Theresa May to choose between the huge political and economic costs of “no deal” or acceding to the EU’s demands – has worked for it so far. May has agreed to pay up, secure citizens’ rights, and negotiated a form of words on the Irish border vague enough to appease Dublin, Belfast, Westminster and Brussels. The next deadline is March 2018, the first point at which the EU will be ready to talk about the future relationship. EU officials are calling for May to spell out in more detail what sort of relationship she wants before then.

So May has three months to find a consensus among her cabinet colleagues on a desired Brexit end-state. She will need to balance the demands of hardliners such as Liam Fox, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson, with those of Philip Hammond and other moderates. But, given her Brexit red lines, the EU will offer a standstill transition for two or three years, in exchange for a non-binding political declaration sketching a trade deal far worse than single market membership.

A standstill transition will let Britain stay in the single market, but the UK won’t have any votes in the council, a commissioner or any members of the European parliament. The UK will have to continue to respect freedom of movement, and continue to be subject to EU laws, including any new laws that are enacted during the transition period. More than 12,000 directives, regulations, European court of justice judgments, and other decisions were made by the EU’s institutions in 2016. The vast majority are uncontroversial, but some will be difficult to accept.

This raises questions about whether Brexiters will accept the transition. Consider EU directives. These are EU laws that must be passed either by the government, using statutory instruments, or, in the case of more important laws, by parliament. The commission will propose new capital markets legislation in 2018, which will have an impact on the City of London; rules for taxing the profits of digital companies; and laws that make it easier for police forces to share electronic evidence. Some of these proposals will not be passed by the council and European parliament. Others will be ready for legislation once Britain has left the EU in 2019, but while it’s still in the transition period – it takes 18 months on average for commission proposals to become law. The passage of new EU directives may prompt revolts by Brexiters against their own government (if the Conservatives remain in power until then). If Britain refuses to pass the legislation, a political crisis will ensue. The commission might take the British government to the European court of justice.

After decades of agitating against the EU, and enjoying power without responsibility, the Conservative right has proposed no method of Brexit that would not result in large economic and political costs. Leaving with no deal is not an option for an economy that is deeply intertwined with that of the continent. A chaotic Brexit would bring down the government and might destroy the Conservative party altogether. A standstill transition should be a certainty. It’s all that is on offer, and it is the only way out of the EU that avoids the cliff edge, providing the political space to deliver a Brexit outcome that will not bring down the government. But Brexiters will have to swallow a transition in which Britain has less sovereignty than it had as an EU member.

What’s more, signing up to the terms of the transition will not buy Britain a comprehensive trade deal. May and David Davis have not yet accepted – at least publicly – that the trade deal will be limited in scope, and will not be ready to be signed “minutes” after Britain’s formal exit at the end of March 2019. The EU will not countenance a trade deal that covers services, the UK’s strongest exporting sector, if May refuses to accept free movement, to abide by past EU rules and download new ones swiftly and automatically. But the Canada-style deal will come with strings attached – rules that prevent the government providing aid to British businesses, and provisions that stop social and environmental “dumping” (the EU, led by France, wants to prevent British firms gaining a competitive advantage through deregulation). The EU will only agree to an outline of the deal before Brexit, the details of which will be negotiated after exit. There will be no guarantees that the trade deal will be ratified by the EU, as it will probably need to go through national and regional parliaments.

At the start of each stage of the Brexit process, May has first been combative to keep her party together, then, as the EU’s deadlines draw near, she has persuaded her party to support a climbdown. We’ve seen it with the sequencing of the talks, upholding EU citizens’ rights, the money and Northern Ireland. By March she will again have to persuade hardliners that avoiding “no deal” requires a transition on the EU’s terms. Can she make it work next time?

John Springford is director of research at the Centre for European Reform in London.