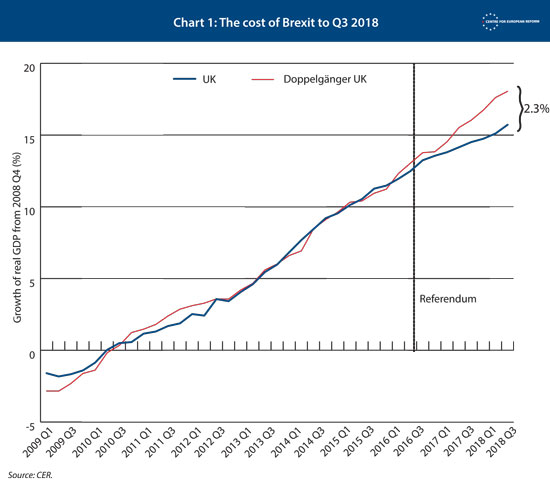

The UK economy is 2.3 per cent smaller than it would be if Britain had voted to remain in the European Union. The latest update of the Centre for European Reform’s calculation of the cost of Brexit by the third quarter of 2018 shows a slight reduction compared to our second quarter estimate, which put the cost at 2.5 per cent. The knock-on hit to the public finances is £17 billion per annum – or £320 million a week.

Our estimate has dipped slightly because UK growth outperformed that of our ‘doppelgänger UK’ – a group of countries whose economic characteristics match Britain’s. As these countries did not hold a referendum in 2016, we can compare them to the UK to assess the cost of Brexit. The British economy grew by 0.6 per cent in the three months to September 2018, its fastest rate since the last quarter of 2016. But our doppelgänger includes Germany, which had a bad third quarter, with its economy shrinking by 0.3 per cent.

Quarterly GDP growth is variable, and poor performance in one country in one quarter can affect the results. This is why it is important to interpret this analysis as a central estimate with a margin of error around it, as discussed below.

However, the basic story is unchanged: Britain’s decision to leave the EU damaged growth, largely thanks to higher inflation and lower business investment. The UK missed out on a broad-based upturn in growth among advanced economies in 2017 and early 2018. And the economic cost of the decision so far is sizeable, if not disastrous.

The data that makes up the UK doppelgänger was selected by a

computer program from a group of 22 advanced economies. It includes quarterly real GDP and other economic indicators, going back to the first quarter of 2009. Once the doppelgänger has been created, we can chart how it compares to the real UK, both before and after the referendum.

The countries the program selected include the US (whose growth rate makes up 50 per cent of that of the UK doppelgänger), Germany (28 per cent), Luxembourg (11 per cent), Iceland (10 per cent) and Greece (2 per cent). The structure of each country’s economy – and their growth rates – are different to those of the UK. But in combination, they closely match the UK’s economic performance before the referendum.

Chart 1 shows that the doppelgänger UK closely matched the economic growth of Britain until the referendum vote, but then the two series diverged. The cost of Brexit is the difference between the doppelgänger’s growth and the UK’s actual growth data. Our latest estimate shows the economy is 2.3 per cent smaller than it would have been if Remain had won.

It is possible to work out how much extra government borrowing the UK’s foregone output implies. The following fiscal estimate is based on the government’s November 2018

analysis of the cost of the various Brexit options, which appraised how membership of the European Economic Area, a free trade agreement, or relying on World Trade Organisation rules to trade with the EU, would hit the economy and public finances. (Our previous estimate was based upon the less comprehensive, leaked

analysis of January 2018). The newer government study was based on a detailed analysis of taxes raised from different sectors of the economy, and how these Brexit options would damage them.

Because we have used the new, more comprehensive government analysis, the fiscal cost has fallen compared to our estimate for the second quarter of 2018. The government found that 1 per cent of lost GDP resulted in £7.6 billion of extra borrowing. Since we have found that the cost so far is 2.3 per cent, that adds up to £17 billion additional borrowing per year. Our estimate shows there is no Brexit dividend: the Leave vote is now costing the Treasury £320 million a week. It also implies that the UK’s fiscal deficit would have largely been eliminated in the 2018-19 financial year if Britain had voted to Remain. Borrowing was falling at a

steady pace in the years before the referendum: it is now growing again (in part, however, because of higher government spending on the NHS and other public services).

Some caveats are in order. First, the 2.3 per cent gap is a central estimate with a margin of error. Before the referendum, on average our doppelgänger deviated from the real UK by 0.26 percentage points in any given year. Second, the group of countries that make up the doppelgänger match the UK closely before the referendum, but we cannot rule out a positive ‘shock’ to some of the countries afterwards – such as a surge in global demand for their exports – which the UK would not have enjoyed even if it had voted for Remain. That said, it is hard to say what growth the UK might have missed out on, given the broad-based global upswing in 2017. And our method is better than a method that compares UK performance

before the referendum to its growth rate after it, since that takes no account of the fact that most economies were growing faster in 2017 than their pre-crisis trend, and one would expect the UK to be participating in that faster growth.

One way to sanity-check our estimate is to compare the UK’s growth to that of other comparable countries since the referendum. The UK has grown by 3.7 per cent over that period. Compare that to the average of the 22 most advanced economies: 5.6 per cent. That amounts to a 1.9 per cent gap, not far from our estimate of the cost of Brexit. Our doppelgänger is selected from 22 countries the IMF labelled as fully industrialised in 1995, to remove any countries that are experiencing faster rates of catch-up growth.

The CER will continue to update our model as new quarterly GDP data comes in – and as a result, we will have a decent basis to test the claims made by Leave and Remain. So far, ‘Project Fear’ continues to be closer to the truth.

For more information on our method, please read the appendix of our previous estimate, here. Interested readers can also see the source dataset here, the STATA script here and the results here. John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform.